急性冠状动脉综合征患者经皮冠状动脉介入治疗术后抗栓与出血风险评估

2018-01-02席少枝尹彤陈韵岱

席少枝 尹彤 陈韵岱

急性冠状动脉综合征患者经皮冠状动脉介入治疗术后抗栓与出血风险评估

席少枝 尹彤 陈韵岱

急性冠状动脉综合征;经皮冠状动脉介入治疗;抗栓治疗;出血风险;模型

随着新型抗栓药物和经皮冠状动脉介入治疗(percutaneous coronary intervention, PCI)的进展,急性冠状动脉综合征(acute coronary syndrome, ACS)患者PCI术后缺血事件发生率显著降低,但是出血发生率明显上升,并且已经成为ACS患者PCI术后发生率最高的并发症之一[1]。近年来越来越多的研究证实,ACS患者PCI术后不同阶段(围术期、院内及院外30 d内、院外长期)的出血发生率以及其对死亡的影响存在一定的差异,ACS患者PCI术后出血多见于PCI术后30 d内,因出血引起患者死亡的多见于出血发生后30 d内[2-4]。除外基线出血相关因素,不同阶段的出血相关因素也存在一定差异。PCI围术期、院内及院外30 d内出血的相关危险因素取决于围术期抗栓治疗策略及PCI术中相关因素[5-9];而院外长期出血取决于院外抗栓治疗策略的选择[不同的双联抗血小板治疗(dual antiplatelet treatment,DAPT)组合方式、DAPT治疗时长及三联抗栓治疗(DAPT+口服抗凝药物治疗等)][10-13]。上述研究表明,临床医师应根据ACS患者PCI术后不同阶段评估出血风险,进而采取相应避免出血的策略,尽可能实现相对精准的出血风险预测以及实施干预,达到改善ACS患者PCI术后临床结局的目的。本文将针对ACS患者PCI术后不同阶段出血发生率与临床转归、出血相关危险因素及出血风险评估模型进行全面的综述。

1 ACS患者PCI术后不同阶段出血发生率与临床转归

2003年GRACE研究[5]表明,有效的抗血小板治疗救治大量ACS患者的同时亦增加了出血发生率。已有研究表明,ACS患者PCI围术期出血约50%见于动脉穿刺部位,ACS患者出血风险已受到关注[6]。随着PCI技术发展及围术期避免

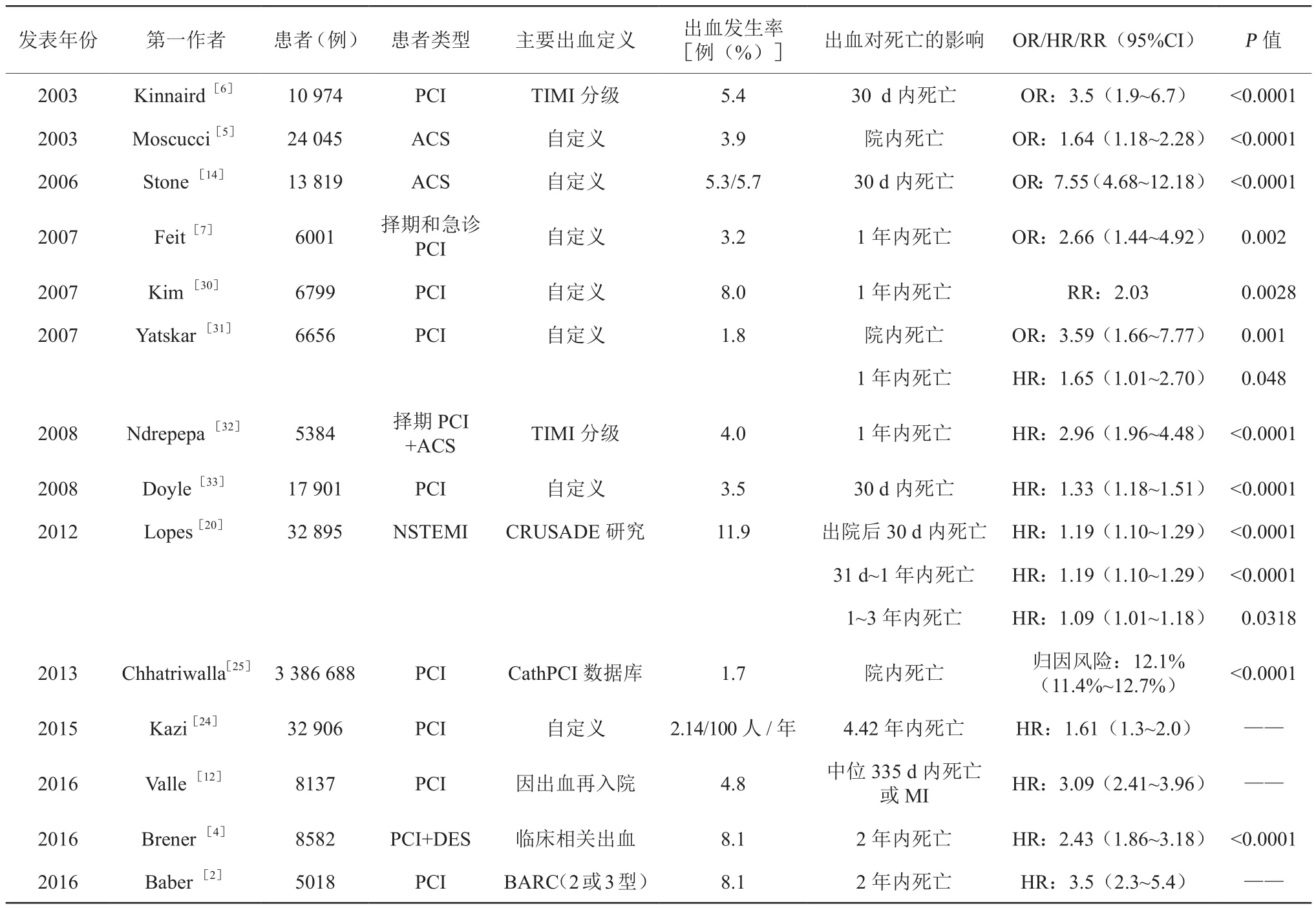

出血策略(经桡动脉入径、血管封堵器使用、新型抗凝药物等)的不断出现,出血发生率(尤其是穿刺部位出血)呈现明显下降趋势,但是ACS患者PCI围术期主要出血发生率仍有0.7%~5.4%[2,4,14]。近年来,随着新型 P2Y12受体抑制剂(替格瑞洛、普拉格雷等)问世及在国内外相关指南包括2014欧洲心脏病学会(ESC)/欧洲心胸外科学会(EACTS)心肌血运重建指南[15],2015ESC非ST段抬高型急性冠状动脉综合 征(non-ST-segment elevation acute covonary syndrome,NSTE-ACS)管理指南[16],2016年中国 PCI指南[17],2016美国心脏病学会(ACC)/美国心脏协会(AHA)冠心病双联抗血小板指南(更新)[18]强调行PCI术的ACS患者院内及院外 30 d 内主要出血发生率为 0.7%~11.9%[2,4,9,14,19-20],院外长期出血发生率为 1.4%~14.9%[6-8,10,12,21-28]。ACS 患者 PCI围术期、院内及院外30 d内、院外长期主要出血均会增加患者院内、院外30 d内、院外1年以及远期的死亡风险,且死亡多见于出血发生后 30 d 内(表 1)[2-7,12,14,20,24-25,28-34]。出血增加死亡风险的可能原因是出血引起贫血、休克、输血以及暂停DAPT的发生,进而导致缺血、炎症以及支架内血栓形成,从而增加死亡的发生率[3]。但是目前少有研究报道出血事件与死亡风险之间是否存在直接的因果关系。

2 ACS患者PCI术后不同阶段出血相关危险因素

ACS患者PCI围术期、院内及院外30 d内出血相关的危险因素主要包括两个方面:(1)基线出血相关因素例如年龄、女性、低体重、高血压病史、慢性肾功能不全、既往PCI史、贫血、ST段抬高型心肌梗死( ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, STEMI)/非ST段抬高型心肌梗死(non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction,NSTEMI)及白细胞升高[5-9];(2)PCI术中出血相关因素例如经股动脉入径行PCI术、慢性完全闭塞性病变、术中紧急使用主动脉内球囊反搏术(intraaortic balloon pump, IABP)、术中低血压、使用阿昔单抗、使用肝素+血小板膜糖蛋白(GP)IIb/IIIa受体拮抗剂、手术时长>1 h及手术起始至鞘管移除时长>6 h等[31]。而院外长期出血相关危险因素不同于急性期(围术期、院内及院外30 d内)出血相关危险因素,除了基线出血相关因素(年龄、女性、低体重、贫血、白细胞升高、高血压病史、外周动脉疾病、既往出血病史,慢性肾功能不全、钙化病变、冠状动脉分叉病变),亦包含院外抗栓治疗相关因素[(氯吡格雷低反应性、强效抗栓药物(替格瑞洛、普拉格雷等)、DAPT治疗时长、长期口服抗凝药物、出院时三联抗栓治疗[10-13])]。

3 ACS患者PCI术后不同阶段出血风险评估的预测模型

当前的出血风险预测模型主要是基于大规模随机对照研究(randomized controlled trial, RCT)[35-48]和观察性注册研究[26,49-50],分别针对特定ACS患者PCI术后不同阶段(围术期、院内及院外30 d内、院外长期)预测出血的发生风险(表2)。下面将针对三个不同阶段的出血预测模型从适用人群、模型的优缺点角度进行阐述。

3.1 围术期出血风险预测模型

3.1.1 经股动脉入径行PCI术的围术期出血预测模型 2007年基于 REPLACE-2 研究[35]以及 REPLACE-1研究[36],建立经股动脉入径的PCI患者围术期出血预测模型[51],纳入6项参数:年龄、女性、肌酐清除率、贫血、PCI术前48 h使用低分子肝素及使用IABP。随后,2011年基于STEEPLE研究[37],建立经股动脉入径的择期PCI患者围术期出血预测模型[52],纳入3项参数:女性、使用普通肝素(与使用依诺肝素对比)及使用GP Ⅱb/Ⅲa 拮抗剂(与未使用GP Ⅱb/Ⅲa 拮抗剂对比)。然而,经桡动脉入径行PCI术,血管并发症少、出血发生率低、患者痛苦少,已优于股动脉入径成为PCI相关指南推荐入径[8,15-16],2016年 China PEACE 研究[34]结果表明:国内PCI术经桡动脉入径的比例高达79%。并且上述研究均是基于RCT研究,纳入的患者均无法代表临床实际工作中的情况,在很大程度上限制了上述两个出血预测模型的应用。

3.1.2 美国国家心血管注册数据库风险评分体系(NCDR CathPCI)出血预测模型 2013年基于NCDR CathPCI数据库数据,纳入美国1000多个中心的1 043 759例行PCI治疗的患者,建立用于预测PCI术后72 h内出血发生风险的NCDR CathPCI 出血预测模型[53-54]。纳入10项参数 :女性、年龄、体重指数(body mass index,BMI)、STEMI、既往 PCI史、慢性肾病、休克、24 h内心搏骤停史、血红蛋白及PCI状态(择期PCI、急诊PCI、紧急或补救性PCI)。该模型是建立在美国临床实际工作中1000多个中心的,近百万PCI患者的基础上,预测相关因素容易获知,具有广泛适用性。但由于未纳入PCI术当天死亡的患者,在一定程度上影响对此类患者的预测精准性。

3.2 院内及院外30 d内出血预测模型

目前针对这个阶段的出血预测模型主要有CRUSADE、ACUITY以及ACTION出血预测模型,其中CRUSADE及ACUITY出血预测模型已经广泛应用于临床。

表1 ACS患者PCI术后主要出血对不同阶段死亡的影响

表2 ACS患者PCI术后不同阶段出血风险预测模型

3.2.1 CRUSADE出血预测模型 2009年基于纳入89 134例高危 NSTEMI患者的CRUSADE注册研究[49-50],建立CRUSADE院内出血预测模型[55],纳入8项参数:血细胞比容、肌酐清除率、心率、女性、心力衰竭、既往血管病史、糖尿病史及收缩压。患者就诊数小时内可根据基线信息获取所有评分参数,算法简便,且可以有效识别是接受两种及两种以上抗血小板药物治疗还是少于两种抗血小板药物治疗,可有效评估接受有创或保守治疗患者的出血风险,非常便于早期指导治疗,临床实用性强。近年来,一些研究亦证实 ,CRUSADE对ACS或PCI患者院内出血风险具有良好预测价值(C值约为 0.7)[58-66];2011ESC NSTE-ACS 管理指南[67]首次推荐CRUSADE评分用于评估NSTE-ACS患者院内出血风险;目前国内已广泛应用CRUSADE评分预测ACS患者院内出血风险。然而CRUSADE评分的建立是基于给予氯吡格雷患者,并未纳入合并口服抗凝药物患者,故其对于服用新型抗血小板药物(普拉格雷、替格瑞洛等)以及合并口服抗凝药物患者的出血风险预测价值有待验证。

3.2.2 ACUITY出血预测模型 2010年基于纳入13 819例ACS患者的ACUITY研究[38]和纳入3602例STEMI+PCI患者的HORIZONS-AMI研究[39],建立 ACUITY出血预测模型[56],用于预测30 d内主要出血发生风险,包括7项参数、女性、年龄、血肌酐、白细胞升高、贫血、ACS亚型[STEMI、NSTEMI、不稳定型心绞痛(unstable angina,UA)]及抗凝策略(普通肝素+GP Ⅱb/Ⅲa受体拮抗剂 、单用比伐芦定)。验证研究亦证实,ACUITY评分对ACS/PCI患者院内出血具有良好预测价值(C值约为 0.74)[60-61,64-66]。前期研究显示,ACS 患者 PCI术后出血主要见于PCI术后30 d内,故ACUITY评分有利于指导个体化抗栓治疗,改善出血与缺血风险[2]。2015ESC NSTE-ACS管理指南[16]再次推荐CRUSADE评分以及ACUITY评分可用于评估行冠状动脉造影的NSTE-ACS患者的院内出血风险。然而ACUITY评分的建立同样主要基于给予氯吡格雷患者,且未纳入合并口服抗凝药物患者,故其对于服用新型抗血小板药物(普拉格雷、替格瑞洛等)以及合并口服抗凝药物患者的出血风险预测价值亦有待验证。

3.2.3 ACTION出血预测模型 2011年基于美国251家医院的90 273例急性心肌梗死(acute myocardial infarction,AMI)患者的ACTION Registry-GWTG数据库[68]数据,建立ACTION院内出血预测模型[57]。与CRUSADE、ACUITY出血评分相比,ACTION评分亦具有良好预测价值(C值约为0.7)[60-61,64-66]。ACTION 评分中首次纳入“既往在家服用华法林治疗”为参数,充分考虑到合并口服抗凝药物治疗的高危出血风险人群。ACTION评分中的参数均为入院基线信息,容易获取,但纳入变量较多(共12项),且计算相对繁杂,故限制了其在临床上的推广应用。

3.3院外长期出血预测模型

目前针对这个阶段的出血预测模型主要有DAPT、PRECISE-DAPT及PARIS出血预测模型,上述出血预测模型均问世不久,在国内尚无大规模型研究人群验证且在临床上尚未广泛应用。

3.3.1 DAPT 预测模型 2016 年建立 DAPT 预测模型[69],用于评估PCI术后12~30个月内出血(GUSTO标准)与缺血(心肌梗死和支架内血栓形成)综合获益风险,包括9项参数:年龄、当前吸烟史、糖尿病史、心肌梗死、既往PCI或心肌梗死(myocardial infraction, MI)史、紫杉醇洗脱支架、支架直径<3 mm、心力衰竭或心脏射血分数<30%及静脉旁路移植血管干预。DAPT预测模型是基于DAPT注册研究[40],该研究纳入11个国家11 648例行PCI术+药物洗脱支架(drug eluting stents, DES)或裸金属支架(bare metal stents,BMS)+ DAPT治疗1年后的患者,随机分为延长阿司匹林+噻氢吡啶类抗血小板药物治疗18个月组和单独阿司匹林治疗18个月组)。该模型是首个预测PCI术后12~30个月内发生主要出血与缺血综合获益风险模型,旨在评估PCI术后12个月延长DAPT治疗是否会带来出血与缺血风险的综合获益。然而,该研究排除了在PCI术后12个月内发生主要出血和缺血事件的患者;该模型并未纳入同时是缺血和出血的独立预测因素(外周动脉疾病、肾功能不全和高血压病);模型的建立是以假设主要缺血和出血对临床结局影响一致为前提,但在实际临床工作过程中并非如此。因此,应谨慎选择该模型应用的适宜人群,且仍需在大样本人群验证。

3.3.2 PRECISE-DAPT及PARIS出血预测模型 2017年基于全球12个国家的8个多中心临床随机对照试验[41-48],纳入行PCI术+支架置入+DAPT治疗的14 963例冠心病患者(其中88%患者给予阿司匹林+氯吡格雷治疗),建立用于预测冠心病+支架置入患者院外7 d以后DAPT治疗期间(中位随访期为552 d)出血发生风险(TIMI标准)的PRECISE-DAPT出血预测模型[70],包括5 项参数:年龄、肌酐清除率、血红蛋白、白细胞升高及既往出血病史。该模型适用于预测PCI术后接受不同时长DAPT治疗患者的出血风险,且纳入“既往出血病史”为参数,充分考虑高危出血患者PCI术后不同时长DAPT治疗的出血风险,弥补了DAPT出血预测模型无法预测PCI术后12个月内发生出血风险的缺点,为临床医师针对此类高危出血患者的抗栓治疗提供参考;作为首个纳入新型抗血小板药物治疗(替格瑞洛、普拉格雷)患者的前瞻性队列研究[PLATO[71]和BernPCI(NCT02241291)注册研究]中进行验证的出血预测模型,其对于接受新型抗血小板治疗的PCI患者亦具有良好的预测出血的价值。在PLATO研究中验证时,因为数据库本身的问题,既往出血病史仅纳入消化道出血病史,因此可能低估了PLATO研究人群的出血风险;由于普拉格雷只应用于低出血风险的患者,导致模型对于接受普拉格雷治疗患者的预测能力欠佳;未纳入合并口服抗凝药物治疗的患者,故对其预测价值有待验证。2016年基于纳入美国和欧洲国家中4190例行PCI术+DES治疗的患者PARIS注册研究[26],建立了用于预测行PCI术+DES患者院外2年内发生出血风险(BARC标准)的PARIS出血预测模型[11],该模型包括6 项参数:年龄、BMI、当前吸烟史、贫血、肌酐清除率及出院时接受三联抗栓治疗。经过在 ADAPT-DES[72]及 PLATO[71]注册研究中的验证,其具有可接受的预测价值(C值≥0.64)。作为首个预测PCI患者院外2年内出血风险模型,同时建立了缺血风险预测模型,旨在初步探索根据出血与缺血风险预测模型选择DAPT治疗时长。然而,该研究中患者采用不同的非随机化的DAPT停药模式,无法代表临床实际工作中不同的DAPT停药模式,一定程度上限制了其临床应用。

综上所述,不同的出血预测模型侧重预测的人群、出血发生阶段不同,适用的临床情况也存在差异,故临床医师应根据特定的行PCI术的ACS患者的不同阶段选择适合的出血预测模型,同时除DAPT预测模型(仅适用于预测行PCI术治疗12个月后是否适合延长DAPT治疗),均需结合临床缺血风险预测模型,如GRACE评分[73]和PARIS缺血预测模型[11],尽可能权衡出血与缺血风险,指导临床个体化抗栓及其他相关治疗策略。

针对行PCI术的ACS患者的出血风险评估,目前国内主要存在的问题:缺乏基于中国多中心、大样本行PCI术的ACS患者的出血风险预测模型; 对ACS患者PCI术后出血风险评估的意识不足、实践不足。目前临床上多数仍依靠医师的经验与直觉判断患者的出血风险,而这种“临床直觉”评估会低估患者的临床风险[74]。目前国内仅对CRUSADE、ACUITY以及ACTION出血预测模型在小规模或单个临床中心人群中进行评估和验证[66,75],故上述出血风险预测模型均有待于在中国大规模、多中心的人群中进行验证,进而探索适合中国行PCI术的ACS患者的不同阶段出血风险预测模型。

[1] Eikelboom JW, Mehta SR, Anand SS, et al. Adverse impact of bleeding on prognosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes.Circulation, 2006,114(8):774-782.

[2] Baber U ,Dangas G, Chandrasekhar J, et al. Time-Dependent Associations Between Actionable Bleeding, Coronary Thrombotic Events, and Mortality Following Percutaneous Coronary Intervention:Results From the PARIS Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv,2016,9(13):1349-1357.

[ 3 ] Steg PG, Huber K, Andreotti F,et al. Bleeding in acute coronary syndromes and percutaneous coronary interventions: position paper by the Working Group on Thrombosis of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J, 2011,32(15):1854-1864.

[4] Brener SJ, Kirtane AJ, Stuckey TD, et al. The Impact of Timing of Ischemic and Hemorrhagic Events on Mortality After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: The ADAPT-DES Study.JACC Cardiovasc Interv, 2016,9(14):1450-1457.

[ 5 ] Moscucci M,Fox KA,Cannon CP,et al. Predictors of major bleeding in acute coronary syndromes: the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events(GRACE). Eur Heart J, 2003,24(20):1815-1823.

[ 6 ] Kinnaird TD,Stabile E,Mintz GS,et al. Incidence, predictors,and prognostic implications of bleeding and blood transfusion following percutaneous coronary interventions. Am J Cardiol,2003,92(8):930-935.

[ 7 ] Feit F,Voeltz MD,Attubato MJ,et al. Predictors and impact of major hemorrhage on mortality following percutaneous coronary intervention from the REPLACE-2 Trial. Am J Cardiol, 2007,100(9):1364-1369.

[8] Ratib K,Mamas MA,Anderson SG,et al. Access site practice and procedural outcomes in relation to clinical presentation in 439,947 patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention in the United kingdom. JACC Cardiovasc Interv, 2015,8 (1 Pt A):20-29.

[9] Numasawa Y,Kohsaka S,Ueda I,et al. Incidence and predictors of bleeding complications after percutaneous coronary intervention.J Cardiol, 2017,69(1):272-279.

[10] Genereux P, Giustino G, Witzenbichler B, et al. Incidence,Predictors, and Impact of Post-Discharge Bleeding After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, J Am Coll Cardiol,2015,66(9):1036-1045.

[11] Baber U, Mehran R,Giustino G, et al. Coronary Thrombosis and Major Bleeding After PCI With Drug-Eluting Stents: Risk Scores From PARIS. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2016,67(19):2224-2234.

[12] Valle JA, Shetterly S, Maddox TM, et al. Postdischarge Bleeding After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention and Subsequent Mortality and Myocardial Infarction: Insights From the HMO Research Network-Stent Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv,2016,9(6)pii: e003519.

[13] Cuisset T, Deharo P, Quilici J, et al. Benef i t of switching dual antiplatelet therapy after acute coronary syndrome:the TOPIC(timing of platelet inhibition after acute coronary syndrome)randomized study. Eur Heart J, 2017,38(41):3070-3078.

[14] Stone GW, McLaurin BT,Cox DA,et al. Bivalirudin for patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med, 2006,355(21):2203-2216.

[15] Kolh P, Windecker S, Alfonso F, et al. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology(ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery(EACTS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions(EAPCI). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg, 2014,46(4):517-592.

[16] Roき M, Patrono C, Collet JP, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology(ESC). G Ital Cardiol(Rome), 2016,17(10):831-872.

[17] 中华医学会心血管病学分会介入心脏病学组.中国经皮冠状动脉介入治疗指南(2016).中华心血管病杂志 ,2016,44(5):382-400

[18] Levine GN,Bates ER, Bittl JA, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA Guideline Focused Update on Duration of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg,2016,152(5):1243-1275.

[19] Redfors B, Kirtane AJ, Pocock SJ, et al. Bleeding Events Before Coronary Angiography in Patients With Non-ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2016,68(24):2608-2618.

[20] Lopes RD, Subherwal S, Holmes DN, et al. The association of in-hospital major bleeding with short-, intermediate-, and longterm mortality among older patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J, 2012,33(16):2044-2053.

[21] Amin AP, Wang TY, McCoy L, et al. Impact of Bleeding on Quality of Life in Patients on DAPT: Insights From TRANSLATEACS. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2016,67(1):59-65.

[22] Chandrasekhar J, Baber U, Sartori S,et al. Sex-related diあ erences in outcomes among men and women under 55 years of age with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: Results from the PROMETHEUS study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv, 2017,89(4):629-637.

[23] Alexopoulos D, Xanthopoulou I, Deftereos S, et al. Contemporary antiplatelet treatment in acute coronary syndrome patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: 1-year outcomes from the GReek AntiPlatElet (GRAPE) Registry. J Thromb Haemost, 2016,14(6):1146-1154.

[24] Kazi DS, Leong TK, Chang TI, et al. Association of spontaneous bleeding and myocardial infarction with long-term mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2015,65(14):1411-1420.

[25] Chhatriwalla AK, Amin AP, Kennedy KF, et al. Association between bleeding events and in-hospital mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA, 2013,309(10):1022-1029.

[26] Mehran R, Baber U, Steg PG, et al. Cessation of dual antiplatelet treatment and cardiac events after percutaneous coronary intervention(PARIS):2 year results from a prospective observational study. Lancet, 2013,382(9906):1714-1722.

[27] Mehta RH, Parsons L, Rao SV, et al. Association of bleeding and in-hospital mortality in black and white patients with st-segmentelevation myocardial infarction receiving reperfusion. Circulation,2012,125(14):1727-1734.

[28] Fox KA, Carruthers K, Steg PG, et al. Has the frequency of bleeding changed over time for patients presenting with an acute coronary syndrome? The global registry of acute coronary events. Eur Heart J, 2010,31(6):667-675.

[29] Doyle BJ, Rihal CS, Gastineau DA, et al. Bleeding, blood transfusion, and increased mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention: implications for contemporary practice. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2009,53(22):2019-2027.

[30] Kim P, Dixon S, Eisenbrey AB ,et al. Impact of acute blood loss anemia and red blood cell transfusion on mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention. Clin Cardiol, 2007,30(10 Suppl 2):Ⅱ35-43.

[31] Yatskar L, Selzer F, Feit F, et al. Access site hematoma requiring blood transfusion predicts mortality in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: data from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Dynamic Registry,Catheter Cardiovasc Interv,2007,69(7):961-966

[32] Ndrepepa G, Berger PB, Mehilli J, et al. Periprocedural bleeding and 1-year outcome after percutaneous coronary interventions: appropriateness of including bleeding as a component of a quadruple end point. J Am Coll Cardiol,2008,51(7):690-697.

[33] Doyle BJ, Ting HH, Bell MR, et al. Major femoral bleeding complications after percutaneous coronary intervention: incidence,predictors, and impact on long-term survival among 17,901 patients treated at the Mayo Clinic from 1994 to 2005.JACC Cardiovasc Interv,2008,1(2):202-209.

[34] Zheng X, Curtis JP, Hu S, et al. Coronary Catheterization and Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in China: 10-Year Results From the China PEACE-Retrospective CathPCI Study. JAMA Internal Medicine, 2016,176(4):512-521.

[35] Lincoあ AM, Kleiman NS, Kereiakes DJ, et al. Long-term eき cacy of bivalirudin and provisional glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade vs heparin and planned glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade during percutaneous coronary revascularization: REPLACE-2 randomized trial. JAMA, 2004,292(6):696-703.

[36] Lincoあ AM, Bittl JA, Kleiman NS, et al. Comparison of bivalirudin versus heparin during percutaneous coronary intervention(the Randomized Evaluation of PCI Linking Angiomax to Reduced Clinical Events[REPLACE]-1trial).Am J Cardiol,2004,93(9):1092-1096.

[37] Montalescot G, White HD, Gallo R, et al. Enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin in elective percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med,2006,355(10):1006-1017.

[38] Stone GW, Bertrand M, Colombo A,et al. Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage strategY (ACUITY) trial: study design and rationale. Am Heart J, 2004,148(5):764-775.

[39] Mehran R, Brodie B, Cox DA, et al. The Harmonizing Outcomes with RevasculariZatiON and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction(HORIZONS-AMI) Trial: study design and rationale. Am Heart J,2008,156(1):44-56.

[40] Mauri L, Kereiakes DJ, Normand SL, et al. Rationale and design of the dual antiplatelet therapy study, a prospective, multicenter,randomized, double-blind trial to assess the effectiveness and safety of 12 versus 30 months of dual antiplatelet therapy in subjects undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with either drug-eluting stent or bare metal stent placement for the treatment of coronary artery lesions. Am Heart J, 2010,160(6):1035-1041.

[41] Pilgrim T, Heg D, Roき M, et al. Ultrathin strut biodegradable polymer sirolimus-eluting stent versus durable polymer everolimuseluting stent for percutaneous coronary revascularisation(BIOSCIENCE):a randomised, single-blind, non-inferiority trial.Lancet, 2014,384(9960):2111-2122.

[42] Raber L, Kelbaek H, Ostojic M, et al. Eあ ect of biolimuseluting stents with biodegradable polymer vs bare-metal stents on cardiovascular events among patients with acute myocardial infarction: the COMFORTABLE AMI randomized trial. JAMA,2012,308(8):777-787.

[43] Gwon HC, Hahn JY, Park KW, et al. Six-month versus 12-month dual antiplatelet therapy after implantation of drugeluting stents: the Eき cacy of Xience/Promus Versus Cypher to Reduce Late Loss After Stenting (EXCELLENT) randomized,multicenter study. Circulation, 2012,125(3):505-513.

[44] Feres F, Costa RA, Abizaid A, et al. Three vs twelve months of dual antiplatelet therapy after zotarolimus-eluting stents:the OPTIMIZE randomized trial. JAMA, 2013,310(23):2510-2522.

[45] Valgimigli M, Campo G, Monti M, et al. Short- versus longterm duration of dual-antiplatelet therapy after coronary stenting:a randomized multicenter trial. Circulation,2012,125(16):2015-2026.

[46] Kim BK, Hong MK, Shin DH, et al. A new strategy for discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy: the RESET Trial(REal Safety and Eき cacy of 3-month dual antiplatelet Therapy following Endeavor zotarolimus-eluting stent implantation). J Am Coll Cardiol, 2012,60(15):1340-1348.

[47] Colombo A, Chieあ o A, Frasheri A, et al. Second-generation drugeluting stent implantation followed by 6-versus 12-month dual antiplatelet therapy: the SECURITY randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2014,64(20):2086-2097.

[48] Valgimigli M, Patialiakas A, Thury A, et al. Zotarolimus-eluting versus bare-metal stents in uncertain drug-eluting stent candidates.J Am Coll Cardiol, 2015,65(8):805-815.

[49] Hoekstra JW, Pollack CV Jr., Roe MT, et al. Improving the care of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes in the emergency department: the CRUSADE initiative. Acad Emerg Med, 2002,9(11):1146-1155.

[50] Bhatt DL, Roe MT, Peterson ED, et al. Utilization of early invasive management strategies for high-risk patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: results from the CRUSADE Quality Improvement Initiative. JAMA, 2004,292(17):2096-2104.

[51] Nikolsky E, Mehran R, Dangas G, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic risk score for major bleeding in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention via the femoral approach. Eur Heart J, 2007,28(16):1936-1945.

[52] Montalescot G, Salette G, Steg G, et al. Development and validation of a bleeding risk model for patients undergoing elective percutaneous coronary intervention. Int J Cardiol, 2011,150(1):79-83.

[53] Rao SV, McCoy LA, Spertus JA, et al. An updated bleeding model to predict the risk of post-procedure bleeding among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a report using an expanded bleeding def i nition from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry CathPCI Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv, 2013,6(9):897-904.

[54] Brindis RG, Fitzgerald S, Anderson HV,et al. The American College of Cardiology-National Cardiovascular Data Registry(ACC-NCDR):building a national clinical data repository. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2001,37(8):2240-2245.

[55] Subherwal S, Bach RG, Chen AY, et al. Baseline risk of major bleeding in non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction:the CRUSADE(Can Rapid risk stratif i cation of Unstable angina patients Suppress ADverse outcomes with Early implementation of the ACC/AHA Guidelines) Bleeding Score. Circulation, 2009,119(4):1873-1882.

[56] Mehran R , Pocock SJ, Nikolsky E, et al. A risk score to predict bleeding in patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2010,55(23):2556-2566.

[57] Mathews R, Peterson ED, Chen AY, et al. In-hospital major bleeding during ST-elevation and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction care: derivation and validation of a model from the ACTION Registry(R)-GWTG. Am J Cardiol, 2011,107(8):1136-1143.

[58] Abu-Assi E, Gracia-Acuna JM, Ferreira-Gonzalez I, et al.Evaluating the Performance of the Can Rapid Risk Stratif i cation of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress Adverse Outcomes With Early Implementation of the ACC/AHA Guidelines(CRUSADE)bleeding score in a contemporary Spanish cohort of patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. Circulation,2010, 121(22):2419-2426.

[59] Ariza-Sole A, Sanchez-Elvira G, Sanchez-Salado JC, et al.CRUSADE bleeding risk score validation for ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Thromb Res,2013,132(6):652-658.

[60] Abu-Assi E, Raposeiras-Roubin S, Lear P, et al. Comparing the predictive validity of three contemporary bleeding risk scores in acute coronary syndrome. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care,2012,1(3):222-231.

[61] Flores-Rios X, Couto-Mallon D, Rodriguez-Garrido J, et al.Comparison of the performance of the CRUSADE, ACUITYHORIZONS, and ACTION bleeding risk scores in STEMI undergoing primary PCI: insights from a cohort of 1391 patients.Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care, 2013,2(1):19-26.

[62] Jinatongthai P, Khaisombut N, Likittanasombat K, et al. Use of the CRUSADE bleeding risk score in the prediction of major bleeding for patients with acute coronary syndrome receiving enoxaparin in Thailand.Heart Lung Circ ,2014,23(11):1051-1058.

[63] Kharchenko MS, Erlikh AD, Gratsianskii NA. Assessment of the prognostic value of the CRUSADE score in patients with acute coronary syndromes hospitalized in a noninvasive hospital.Kardiologiia, 2012,52(8):27-32.

[64] Taha S, D'Ascenzo F, Moretti C, et al. Accuracy of bleeding scores for patients presenting with myocardial infarction: a metaanalysis of9studies and 13 759 patients. Postepy Kardiol Interwencyjnej, 2015,11(3):182-190.

[65] Correia LC, Ferreira F, Kalil F, et al. Comparison of ACUITY and CRUSADE Scores in Predicting Major Bleeding during Acute Coronary Syndrome. Arq Bras Cardiol, 2015 ,105(1):20-27.

[66] Liu R,Lyu SZ,Zhao GQ, et al. Comparison of the performance of the CRUSADE, ACUITY-HORIZONS, and ACTION bleeding scores in ACS patients undergoing PCI: insights from a cohort of 4939 patients in China. J Geriatr Cardiol,2017,14(2):93-99.

[67] Hamm CW, Bassand JP, Agewall S, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J, 2011,32(23):2999-3054.

[68] Peterson ED, Roe MT, Rumsfeld JS, et al. A call to ACTION(acute coronary treatment and intervention outcomes network):a national eあ ort to promote timely clinical feedback and support continuous quality improvement for acute myocardial infarction.Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes,2009 ,2(5):491-499.

[69] Yeh RW, Secemsky EA, Kereiakes DJ, et al. Development and Validation of a Prediction Rule for Benef i t and Harm of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Beyond1Year After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. JAMA,2016,315(16):1735-1749.

[70] Costa F, van Klaveren D, James S, et al. Derivation and validation of the predicting bleeding complications in patients undergoing stent implantation and subsequent dual antiplatelet therapy (PRECISE-DAPT) score: a pooled analysis of individualpatient datasets from clinical trials. Lancet, 2017,389(10073):1025-1034.

[71] Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med, 2009,361(11):1045-1057.

[72] Stone GW, Witzenbichler B, Weisz G, et al. Platelet reactivity and clinical outcomes after coronary artery implantation of drugeluting stents (ADAPT-DES): a prospective multicentre registry study. Lancet, 2013,382(9892):614-623.

[73] Fox KA, Dabbous OH, Goldberg RJ, et al. Prediction of risk of death and myocardial infarction in the six months after presentation with acute coronary syndrome: prospective multinational observational study (GRACE). BMJ, 2006,333(7578):1091.

[74] Chew DP, Juergens C, French J, et al. An examination of clinical intuition in risk assessment among acute coronary syndromes patients: observations from a prospective multi-center international observational registry. Int J Cardiol, 2014,171(2):209-216.

[75] Li S, Liu H, Liu J. Predictive performance of adding platelet reactivity on top of CRUSADE score for 1-year bleeding risk in patients with acute coronary syndrome. J Thromb Thrombolysis,2016,42(3):360-368.

R541.4

10. 3969/j. issn. 1004-8812. 2017. 11. 007

“十三五”国家重点研发计划(2016):冠状动脉粥样硬化病变早期识别和风险预警的影像学评价体系研究(2016YFC1300300)

100853 北京,中国人民解放军总医院心血管内科

陈韵岱,Email:cyundai@vip.163.com

2017-07-23)