Pathological diagnosis of T-follicular helper cell lymphoma

2021-10-13ZHAOYueJennaMcCrackenWANGEndi

ZHAO Yue, Jenna McCracken, WANG En-di

Author affiliations:Department of Pathology, First Affiliated Hospital and College of Basic Medical Sciences, China Medical University, Shenyang 110001, China(ZHAO Yue);Department of Pathology, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC 27710, USA(ZHAO Yue, Jenna McCracken, WANG En-di)

[Abstract] T-follicular helper cell lymphoma(T-FHCL) is a type of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. The understanding of T-FHCL has been evolving over the course of several decades, and it was classified into three subcategories by the World Health Organization in 2017. Because T-FHCL often has misleading histopathological manifestations and incompletely clarified pathogenesis, its diagnosis is challenging and usually requires a series of multifaceted evaluations, especially for angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma(the most common of the three subcategories). Along with recent advances in the field of molecular biology, the genomic landscape of T-FHCL has been unraveled, and the mechanism underlying its lymphomagenesis, especially the development of its unique microenvironment, is now better understood.In this commentary, we not only summarize the pathological features, the updated diagnostic criteria, and classification of T-FHCL, but also discuss the latest advances in the molecular study of T-FHCL and its application in diagnosis and disease classification.

[Key words] T-follicular helper cell lymphoma; Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; Follicular T-cell lymphoma; Nodal peripheral T-cell lymphoma with T-follicular helper phenotype; Peripheral T-cell lymphoma

1 Introduction—T-follicular helper cell lymphoma(T-FHCL), subcategories and differentiation from other mature T-cell neoplasms

T-FHCL belongs to the category of mature T-cell lymphoma[1-2]. It comprises 1%-2% of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and represents 20%-30% of peripheral T-cell lymphoma(PTCL)[3]. The diagnosis of T-FHCL is more challenging than that of other types of T-cell malignancies, due to its polymorphic cell infiltration that resembles reactive paracortical hyperplasia and difficulty in demonstrating T-cell clonality in a significant number of cases. Figure 1 simplifies the algorithmic approach to the diagnosis by excluding other types of mature T-cell lymphoma. To make a diagnosis of T-FHCL, a pathologist or hematopathologist needs to rule out tissue/organ-specific T-cell lymphomas, which include cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, intestinal T-cell lymphoma, hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma, and mature T-cell leukemia. Next, he/she needs to rule out systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma, a T-cell lymphoma with characteristic hallmark cells displaying homogeneous expression of CD30. The pathologist/hematopathologist then needs to rule in T-FHCL by confirming T-follicular helper(TFH) cell phenotype. If the diagnosis cannot be ruled in, PTCL, not otherwise specified(PTCL-NOS), would be considered as a “wastebasket” diagnosis.

TCL, T-cell lymphoma; MF, mycosis fungoides; C-ALCL, cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma; LyP, lymphomatoid papulosis; CTCL, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma; EATL, enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma; MEITL, monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T-cell lymphoma; HSTCL, hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma; T-LGL, T-cell large granular lymphocytic leukemia; T-PLL, T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia; ALCL, systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma; ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; PTCL, peripheral T-cell lymphoma; PTCL-NOS, peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified; T-FHCL, T-follicular helper cell lymphoma; AITL, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; FTCL, follicular T-cell lymphoma; NPTCL-TFH, nodal peripheral T-cell lymphoma with T-follicular helper cell phenotype

The classification of T-FHCL, particularly angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma(AITL), was initially prompted by identifying its gene expression signature related to benign TFH cells(in contrast to PTCL-NOS)[4]. Antigen markers, including CD10, BCL6, PD1, CXCL13, ICOS, CXCR5, and SAP were subsequently introduced with the first five markers used routinely in most diagnostic immunohistochemical laboratories. These antigen markers have variable sensitivities, with PD1, ICOS, CD10, CXCL13 and BCL6 stains demonstrating 97%, 94%, 44%, 44% and 29% positive predictive values, respectively[5]. To define TFH cell phenotype, the expressions of minimally two, ideally three or more of the above listed markers, are needed, in addition to CD4 and certain T-cell lineage specific antigens[1-2]. Based on histopathologic features, the current World Health Organization(WHO) classification divides T-FHCL into three subcategories: AITL, follicular T-cell lymphoma(FTCL), and nodal peripheral T-cell lymphoma with T-follicular helper phenotype(NPTCL-TFHP) for all cases that do not fit within the former two subcategories[2].

2 Clinical features of T-FHCL

All the three subcategories of T-FHCL have similar clinical manifestations, including frequently systemic symptoms, generalized lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, cutaneous involvement with skin rash, pleural effusion, and/or ascites[6-7]. Involvement of extranodal sites is common, with involvement of bone marrow reported in 70% of cases[8]and of lung[9]or intestine[10]in a small percentage. In addition to lymphoma-related constitutional symptoms, patients often present with signs suggestive of autoimmune disease or immunodeficiency such as polyarthritis, vasculitis, thyroid disorders, or opportunistic infections. Laboratory evaluations frequently demonstrate evidence of immune dysregulation, including polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia, circulating immune complexes, autoantibodies, and cold agglutinins. Other laboratory abnormalities include elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase and blood cell changes such as eosinophilia, lymphopenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia[6-7]. While the symptoms may wax and wane in some cases, the majority of patients manifest an aggressive clinical course and dismal outcome without timely therapy.

3 Histopathologic classification of T-FHCL

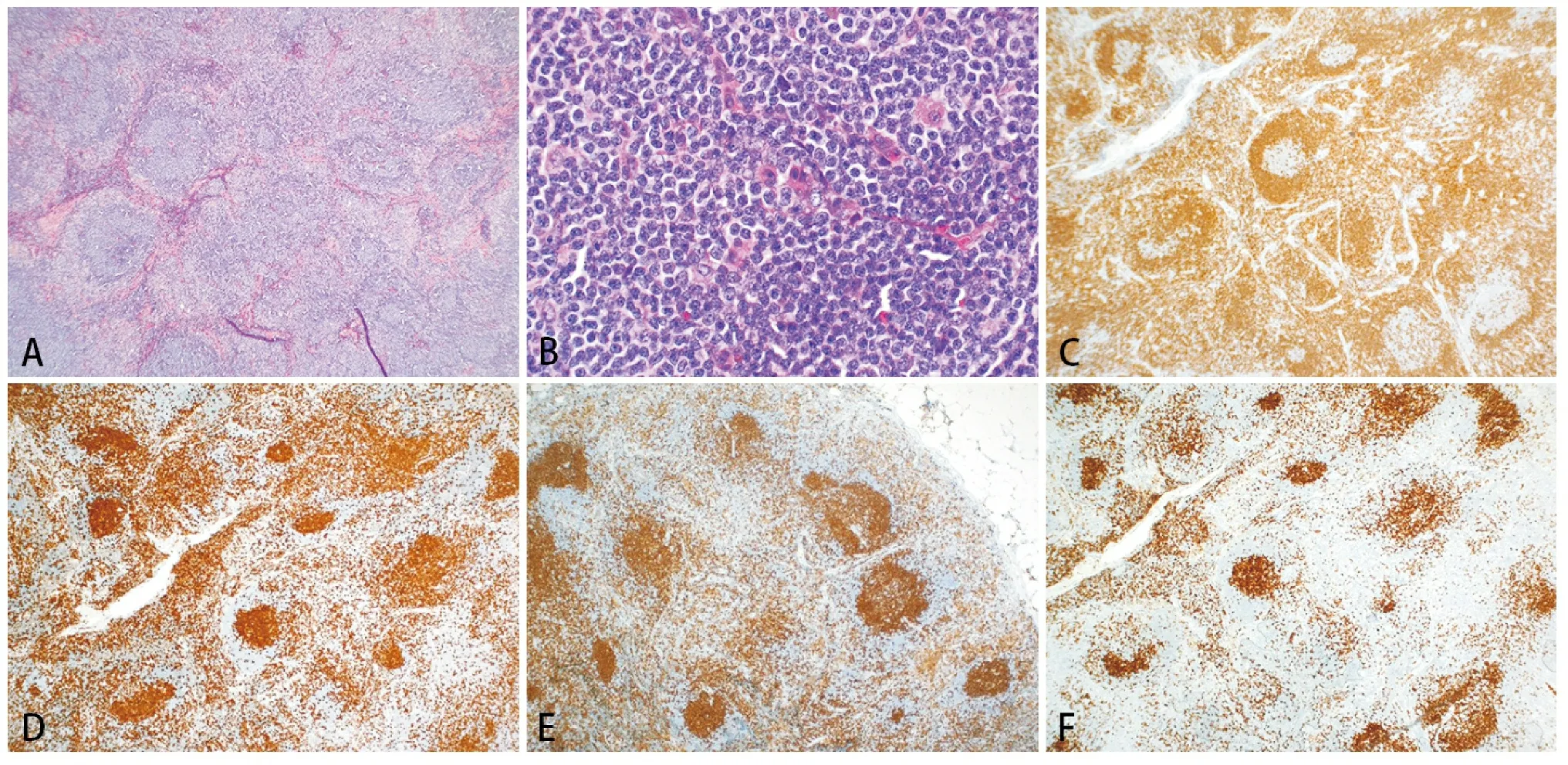

The immunophenotypic profile is similar among the three subcategories, and the distinction is based on histopathologic features, including several morphologic variants within each subcategory. AITL is characterized by a polymorphic cell infiltrate, increased high endothelial venules, and prominent follicular dendritic meshworks which can be highlighted by CD21/CD23 stains and are often expanded beyond lymphoid follicles. Reactive components including small lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils are commonly increased and neoplastic T-cells, which vary in number from case to case, are typically medium in size with clear cytoplasm and frequently form aggregates[2-3]. Three morphologic variants, including perifollicular, interfollicular, and diffuse growth patterns, can be recognized by immunohistochemical analysis[11]. For instance, the perifollicular variant(pattern Ⅰ) can be highlighted by T-cell marker stains, PD1, CD10, or other follicular antigen stains with positive cells distributed around intact or atrophic germinal centers(Figure 2A-C). This morphologic variant is least frequent among the three growth patterns of AITL, and could be considered an early lesion, in contrast to diffuse variant(pattern Ⅲ)[12]. This diagnosis is particularly challenging because it resembles reactive follicular hyperplasia. As its name implies, the interfollicular variant(pattern Ⅱ) has neoplastic cells distributed between lymphoid follicles(Figure 2D-F). The most common variant is the diffuse growth pattern(pattern Ⅲ) with nodal architecture effaced completely or near-completely(Figure 2G-I), which comprises approximately 80% of AITL. The three patterns may represent chronologic manifestations or consecutive progression of the same disease, with perifollicular and interfollicular variants representing relatively early phase of AITL[12]. Of note, more than one pattern may be seen in different lymph node biopsies of the same patient,reflecting varied involvement by the lymphoma.

A-C, pattern Ⅰ, perifollicular distribution of neoplastic T-cells. A, H&E stain, ×40; B, CD3 stain, ×100 and C, PD1 stain, ×100. Note the intact follicles(A) and perifollicular distribution of T-cells(B) with expression of PD1(C). D-F, pattern Ⅱ, interfollicular distribution of neoplastic T-cells. A, H&E stain, ×100; B, CD3, ×100 and C, CD4, ×100. Note the interfollicular distribution of CD4 subset-restricted T-cells. G-I, pattern Ⅲ, diffuse infiltration of neoplastic T-cells. G, H&E stain, ×200; H, CD3 stain, ×100 and I, EBER CISH, ×100. Note the atypical lymphocytes with clear cytoplasm and proliferation of high endothelial venules in the background(G), predominant T-cell infiltration(H), and scattered cells with EBV latent infection(I).

In FTCL, nodal architecture is completely or partially effaced by a nodular(follicular) proliferation of medium-sized lymphocytes with a moderate amount of clear cytoplasm. Immunohistochemical analysis often shows an inverted pattern of B-cell and T-cell distribution, with T-cells in the center of lymphoid follicles surrounded by B-cells(Figure 3)[7,13].In addition,T-cells within lymphoid follicles demonstrate expression of follicle center antigens(Figure 3F), usually with CD4 subset restriction(Figure 3E). CD21 often highlights well-formed follicular dendritic meshworks underneath the lymphoid follicles, as seen in follicular lymphoma. At the present time, two morphologic variants are recognized: follicular growth pattern and progressive transformation of germinal centers(PTGC)-like growth pattern[7]. In the follicular variant, the neoplastic growth resembles follicular lymphoma on H&E section, but immunohistochemical analysis demonstrates an inverted distribution of T-cells and B-cells with T-cells in the center of lymphoid nodules surrounded by mantle zone B-cells(Figure 3)[13]. In contrast to the follicular variant, a PTGC-like growth pattern has dispersed neoplastic T-cells, frequently forming small clusters, within large lymphoid nodules rich in B-cells. The neoplastic T-cells often show irregular nuclear contours and a moderate amount of clear cytoplasm. The B-cell-rich nodules result from expanded mantle zones or germinal centers replaced by mantle zone cells that are typically positive for IgD[14]. This morphologic variant, particularly those cases with a very low number of neoplastic T-cells, is easy to miss without careful examination of immunohistochemical stains to confirm the morphologic atypia and phenotypic aberrancy of the neoplastic T-cells.

A, H&E stain, × 40. Note the follicular growth pattern with peripheral halo, suggesting an inverted follicular growth. B, High magnification shows the center of a follicle. Note the monotonous small to medium-sized lymphocytes with no nuclear cleft characteristic of centrocytes. H&E stain, ×400. C, CD20 stain, ×40. Note the peripheral distribution of B-cells corresponding to the halo around the neoplastic “follicles”. D, CD3 stain, ×40; E, CD4, ×40 and F, CD10, ×40. Note the central localization of T-cells in the follicles(D) with CD4 subset restriction(E) and co-expression of CD10(F).

Cases with TFH cell phenotype, but which do not fit into either AITL or FTCL, would be classified as NPTCL-TFH as a provisional category, per the current WHO classification[2].

All the three subcategories of T-FHCL are frequently associated with latent Epstein-Barr virus(EBV) infection(Figure 2I). This bystander infection could lead to clonal expansion of an EBV-positive B-cell population, resulting in an EBV-positive B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder, either concomitant with T-FHCL or relapsed as EBV-positive B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder without detectable T-cell clone(status-post treatment)[15]. In a case with AITL-like morphology and scattered EBV-positive cells but no evidence of T-cell clonality, an infectious mononucleosis lymphadenopathy needs to be excluded by correlating with clinical findings and laboratory data,such as EBV serology and viral genome copies in the blood.

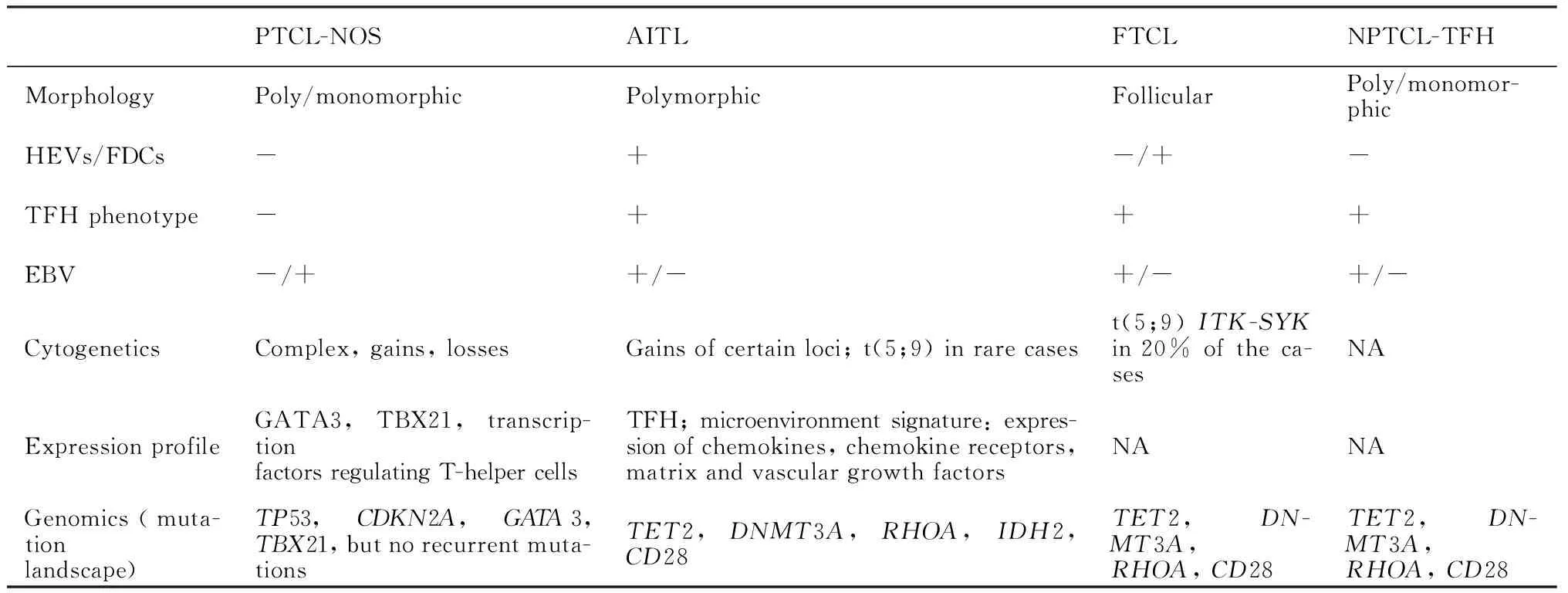

More importantly, the three subcategories of T-FHCL may have overlapping histopathologic features in concurrent biopsies of different lymph nodes or sequential biopsies of the same patient, which may represent morphologic variation of the same disease. For example, a case with an initial diagnosis of FTCL may relapse as a typical AITL or vice versa[7,13]. The distinction between T-FHCL and PTCL-NOS is based on phenotype, though the morphology can be overlapped. Table 1 shows the diagnostic features of the three subcategories of T-FHCL and their distinctions from PTCL-NOS.

4 Ancillary tests, pathogenesis, and clinical applications of genomic analysis in T-FHCL

AITL is a T-cell lymphoma in which gene expression profile is well characterized, not only in the neoplastic T-cells, but also in the reactive components forming a unique microenvironment[4]. TFH cell expression profile is identified in sorted clonal T-cells from AITL tissue, comparable to that seen in its benign counterpart. The microenvironment consisting of multiple reactive cell populations and endothelial proliferation is generated by release of CXCL13 from neoplastic TFH cells, and other subsequently produced cytokines. While this microenvironment is unique to AITL, in contrast to PTCL-NOS, expression profiling itself is not practical to apply in diagnostic practice, due to low cost-effectiveness, and a surrogate test(immunohistochemical analysis) is thus used to evaluate for follicular helper cell phenotype[11].

As in the diagnosis of other lymphomas, the diagnosis of T-FHCL often requires demonstration of T-cell clonality. This is particularly frequent in the diagnosis of AITL, since it frequently resembles viral lymphadenitis in histology. Evidence of T-cell clonality could be achieved in several ways. First, flow cytometry often demonstrates a fraction of T-cells with either complete loss of certain pan-T-cell antigens(most frequently loss of CD7) or altered intensity of antigen expression[7,11]. If the abnormal T-cells form a discrete cluster, this would be equivalent to light chain restriction in B-cell lymphoma, and serves as evidence of T-cell clonality. Second, T-cell receptor(TCR) gene rearrangement analysis could be performed on paraffin-embedded tissue if flow cytometry does not identify a population of phenotypically abnormal T-cells. Ninety percent of AITL have their T-cell clone detected by BiomedTCRGand/orTCRBgene rearrangement analysis[16-17]. Introduction of next generation sequencing into gene rearrangement analysis further improves the detection rate of clonalTCRrearrangement in cases of AITL, and increases the specificity of the test by including sequence identity of the break points and segment usage[18]. Of note, in the perifollicular pattern of AITL and the PTGC-like growth pattern of FTCL, the T-cell clone may be missed by flow cytometry orTCRgene rearrangement analysis due to low level of neoplastic T-cells buried in a background of numerically more frequent reactive components. Lastly,recent advances in genomic analysis make mutational profiling of T-cell lymphoma possible in diagnostic practice. AITL and the other two subcategories of T-FHCL often share a signature mutation landscape, including mutations inTET2,DNMT3A, andRHOAgenes[19-20]. This signature mutation profile can be used not only to confirm T-cell clonality, but also to distinguish T-FHCL from PTCL-NOS, since the latter shows a more heterogeneous and variable mutation landscape(Table 1)[21].

Table 1 Pathological features for the three subcategories of T-FHCL and their distinctions from PTCL-NOS[1,3,7,13-14,19-21]

In molecular pathogenesis,IDH2,TET2,andDNMT3Aserve as epigenetic modifiers, of these,TET2 andDNMT3Amutations are early events or “first hit” mutations in AITL, since they often demonstrate higher mutant allele frequencies in individual cases and are seen in benign cells as well.IDH2R172andRHOAG17Vappear to be associated with T-cell lineage and follicular helper phenotype as well as malignant nature, and thus are considered “second hit” mutations. Mutations in other genes such asVAV1,PLCG1,CD28,CTLA4-CD28,ITK-SYK,VAV1-STAP2andTNFRSF21, observed sporadically in AITL are also considered late events or “second hit” mutations[5,19-20], though the majority of these mutations are not confined to T-FHCL and occur with a similar frequency in PTCL-NOS. FTCL and NPTCL-TFH share a mutational profile with AITL, includingTET2,DNMT3AandRHOAG17Vmutations, butIDH2 mutation is specific to AITL and is associated with proliferation of high endothelial venules and expansion of follicular dendritic meshworks, the morphologic features characteristic of AITL[3,22].

The genomic profile of T-FHCL has clinical implications, such as predicting clinical outcome and directing therapeutic approach. For instance,TET2 andDNMT3Amutations are associated with advanced stage and short progression-free survival in AITL. WhileIDH2 mutation is associated with a poor prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia(AML) and myelodysplastic syndrome, its association with AITL does not seem to predict clinical outcome[20]. Specific mutations can be used as marker for detecting minimal residual disease status-post treatment. As discussed above, in cases of negative clonalTCRgene rearrangement testing and equivocal histopathology, mutation profile can be used to document clonality. More importantly, with further revelation of the genomic landscape and lymphomagenesis, therapeutic targets may be identified, as has been done in the treatment of AML and many solid malignancies[19]. Current treatment for PTCL-NOS and T-FHCL is CHOP[cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, oncovin(vincristine), and prednisone] or CHOP plus etoposide[22]. Five-year overall survival rate for PTCL-NOS is 20%-30%[23]. While AITL is slightly better in outcome, its median survival is less than 3 years according to most studies[6]. Prompted by its successful application in the treatment of myeloid neoplasms withTET2 mutation, the demethylating agent azacytidine has been tentatively used in a small group of patients withTET2-mutated T-cell lymphoma, and demonstrated a good response[24]. Hopefully, along with a better understanding of the biology of T-FHCL, novel targeted treatment modalities can be invented, such as inhibitors to block signal transduction pathways that drive the development of the lymphoma or to introduce an anti-clonal effect, such as CAR T-cells directed against the neoplastic clones[19].

5 Conclusion

Diagnosis of T-FHCL is challenging and relies on a constellation of multifaceted analyses. Recent advances in genomic studies have led to a tremendous progression in understanding the pathogenesis of AITL and other subcategories of T-FHCL. While the genomic landscapes are different between T-FHCL and PTCL-NOS, the three subcategories of T-FHCL share a similar mutational profile, reflecting a variation in histologic pattern of the lymphoma with the same cell origin. These molecular findings may be translated into clinical use, along with accumulating data and further understanding the disease process.