Oncogenic osteomalacia caused by a phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor of the femur: A case report

2019-08-14DongTangXiaoManWangYongShengZhangXiaoXiaoMi

Dong Tang,Xiao-Man Wang,Yong-Sheng Zhang,Xiao-Xiao Mi

Abstract

Key words: Oncogenic osteomalacia; Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor;Hypophosphatemia; Hypocalcemia; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Oncogenic osteomalacia,also known as tumor-induced osteomalacia,is an uncommon cause of osteomalacia.At present,approximately 140 different tumors have been reported in association with oncogenic osteomalacia,and most osteomalaciaassociated tumors are phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors[1,2].Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors are found to be commonly associated with phosphaturia and a decreased level of serum 1,2-dihydroxyvitamin D3 that is resistant to vitamin D supplementation.However,oncogenic osteomalacia caused by phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors is not easily identifiable or detectable due to its rarity and nonspecific presentations.The clinical presentations of the patients include nonspecific symptoms of fatigue,bone pain,and musculoskeletal weakness[3].Although rare,the diagnosis of phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor should be considered in any patient who presents with hypophosphaturic osteomalacia and no other physiologic cause.

In our case,oncogenic osteomalacia was caused by a phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor localized in the patient’s left femur.The patient presented with progressive bone pain with no etiology for five years.After X-ray,computed tomography (CT),magnetic resonance imaging (MRI),and biopsy,a diagnosis of oncogenic osteomalacia caused by a phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor was made.Resection of the tumor was performed,and the clinical presentations and laboratory abnormalities were reversed.Here,our case emphasizes that histologically benign phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors that are responsible for oncogenic osteomalacia can also cause bone destruction.Its diagnosis is,thus,reliably achieved by histopathological examination combined with medical imaging.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 57-year-old woman presented with progressive bone pain of the whole body for three years.

History of present illness

Five years ago,there was no obvious cause for the appearance of pain in her right third toe; pain then developed into the right instep with an associated jerk and then progressively appeared in the right thigh with an associated jerk,thus affecting her ability to walk.Three years ago,systemic pain appeared,especially bone pain.There was also pain in her muscles and skin.Reduction or even no pain was felt while lying flat.At this time,she also had the ability to do laundry or cook.Two years ago,pain prevented her from daily exercise,and she had to stay in bed.There was no accompanying fever,coma,cough,dizziness,headache,chest tightness,palpitation,nausea,vomiting,or abdominal pain.Five years ago,she was first examined at a hospital,and her laboratory workup showed slightly low levels of serum phosphorus(0.63 mmol/L,reference range:0.80-1.48 mmol/L) and low serum calcium (1.98 mmol/L,reference range:2.10-2.60 mmol/L).Bone density examination showed osteoporosis in her left acetabulum and osteopenia in her lumbar spine.Chest and abdomen computed tomographic scans did not reveal any abnormalities.However,the photographs were not available now.She was treated with calcium and vitamin D supplementation.However,her pain persisted.The woman was introduced to our hospital approximately 5 years after the onset of her symptoms.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Physical examination showed that palpation on the right upper abdomen was normal;signs such as purple striae,moon face,and central obesity were not observed.

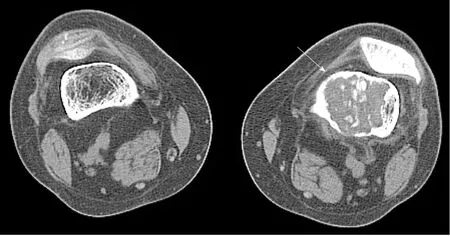

Her laboratory data also revealed slight hypophosphatemia (0.76 mmol/L,reference range:0.80-1.48 mmol/L) and hypocalcemia (1.86 mmol/L,reference range:2.10-2.60 mmol/L).Her knee radiographs showed that her bony trabeculae were sparse and her bone density was widely reduced (Figure 1).The X-ray radiograph showed an oval osteolytic lesion in the inferior medullar cavity of the left femur(Figure 1B,arrow).A subsequent CT scan revealed that mixed density shadows were shown in the intramedullary cavity of the left femur (Figure 2,arrow).Non-uniform enhancement in this lesion area was observed.However,no obvious abnormalities were seen in the surrounding soft tissues.MRI of the left knee showed the presence of an intramedullary tumor in the left femur,which showed a hypointense signal on the T1-weighted image (Figure 3A,arrow) and a high-low mixed signal intensity on the T2-weighted image (Figure 3B and C,arrow).Thus,a tumor-induced osteomalacia was confirmed.

TREATMENT AND OUTCOME

The tumor was resected at a local hospital,and the histology revealed a phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor with the presence of spindle cells and prominent blood vessels(Figure 4).Her serum phosphorus and calcium returned to the normal range(phosphorus:0.89 mmol/L,reference range:0.80-1.48 mmol/L; calcium:2.29 mmol/L,reference range:2.10-2.60 mmol/L),and now the woman can exercise daily and has not had any recent complaints.

DISCUSSION

The existence of tumor-induced osteomalacia is not widely recognized,and its diagnosis can often be delayed[4].Tumors that are involved in oncogenic osteomalacia include phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors,fibrous dysplasia,osteosarcoma,and others[5-7].Folpeet al[2]revealed that 90% of tumor-induced osteomalacia cases are associated with phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors.Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors are most often seen in the head and lower extremities,and approximately 53%of them occur in bone,45% in soft tissue,and 3% in skin[8].Most phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors are seen in middle-aged adults,with no gender difference[9].The histology of phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors features proliferation of spindle cells and oval cells,vascularization,a cartilage-like matrix,and giant cells[10].Although rare,malignant tumors with metastasis and infiltration can also be present[11-13].The present case of phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor occurred in the left femur and led to hypophosphatemia osteomalacia in a middle-aged woman.

Hypophosphatemia in tumor-induced osteomalacia is caused by the mRNA overexpression of FGF-23,a protein that is produced at low levels by osteocytes[10,14].FGF-23 plays important roles in phosphate homeostasis and vitamin D metabolism.After binding with the FGFr1 receptor and the transmembrane protein Klotho,FGF-23 exerts bioactivity at the proximal tubules,where it inhibits phosphate resorption.FGF-23 also impairs the activity of hydroxylation of 25-hydroxyvitamin (OH) D3.These mechanisms mainly lead to hypophosphatemia and osteomalacia[15,16].However,in China,the serum FGF-23 test is not routinely provided in most hospitals.This highlights the need for our clinicians to be aware of its entity and to give an appropriate investigation of phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor-induced osteomalacia.

Figure 1 X-rays of knee joints.

Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors are often very small in size and grow slowly,which makes them difficult to locate[10].Malignant tumors and metastasis can often be detected.Infiltration of the surrounding tissue can also happen.Widespread bone metastases may lead to the occurrence of pathological fractures and spinal cord compression,thus significantly affecting patient outcomes.There are no established guidelines for the treatment of metastatic phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors.Complete tumor resection corrects the biochemical abnormalities and remineralization of bone.In our case,we did not observe metastases of the tumors,and resection of the tumor relieved pain and reversed the biochemical abnormalities in the patient.Our case demonstrated that histologically benign phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors can also cause bone pain.

In conclusion,we report a case of oncogenic osteomalacia caused by a phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor of the left femur in a middle-aged woman.Our case emphasizes that histologically benign phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors that are responsible for oncogenic osteomalacia can also cause bone destruction.Its diagnosis is,thus,reliably achieved by histopathological examination combined with medical imaging.We expect that the detailed description of this case presentation of oncogenic osteomalacia will provide a valuable resource to facilitate the diagnosis of such diseases in the future.

Figure 2 Computed tomography scans of knee joints.

Figure 3 Magnetic resonance imaging of the left knee.

Figure 4 Histology of the resected tumor.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank colleagues from the Department of Radiology and Ultrasound Imaging of Hangzhou Normal University Affiliated Hospital for their support and collaboration.

杂志排行

World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Bone alterations in inflammatory bowel diseases

- Extrahepatic hepcidin production: The intriguing outcomes of recent years

- Neoadjuvant endocrine therapy: A potential strategy for ER-positive breast cancer

- Vestigial like family member 3 is a novel prognostic biomarker for gastric cancer

- HER2 heterogeneity is a poor prognosticator for HER2-positive gastric cancer

- Changes in corneal endothelial cell density in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma