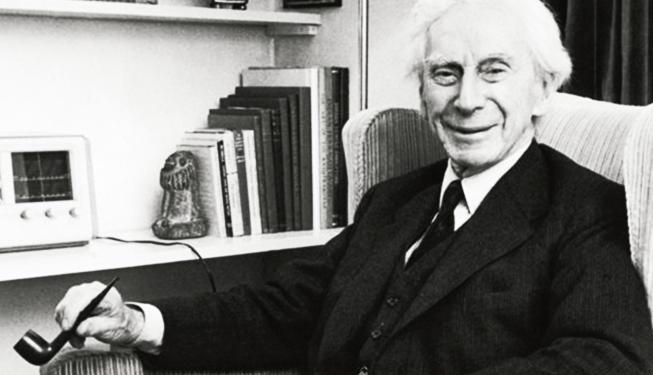

罗素:伦理学和政治学下的人类社会

2018-01-05ByBertrandRussell

By Bertrand Russell

The life of man may be viewed in many different ways. He may be viewed as one species of mammal and considered in a purely biological light. From this point of view his success has been overwhelming. He can live in all climates and in every part of the world where there is water. His numbers have increased and are increasing still faster. He owes his success to certain things which distinguish him from other animals: speech, fire, agriculture, writing, tools, and large-scale co-operation.

It is in the matter of co-operation that he fails of complete success. Man, like other animals, is filled with impulses and passions which, on the whole, ministered to1 survival while man was emerging. But his intelligence has shown him that passions are often self-defeating, and that his desires could be more satisfied, and his happiness more complete, if certain of his passions were given less scope and other more. Man has not viewed himself more at most times and in most places as a species competing with other species. He has been interested,not in man, but in men; and men have been sharply divided into friends and enemies. At times this division has been useful to those who emerged victoriously: for example, in the conflict between white men and red Indians. But as intelligence and invention increase the complexity of social organizations, there is a continual growth in the benefits of co-operation, and a continual diminution2 of the benefits of competition. Ethics and moral codes are necessary to man because of the conflict between intelligence and impulse. Given intelligence only, or impulse only, there would be no place for ethics.

Men are passionate, headstrong, and rather mad. By their madness they inflict upon themselves, and upon others, disasters which may be of immense magnitude. But, although the life of impulse is dangerous, it must be preserved if human existence is not to lose its savour. Between the two poles of impulse and control, an ethic by which men can live happily must find a middle point. It is through this conflict in the innermost nature of men that the need for ethics arises.

Men is more complex in his impulses and desires than any other animals, and from this complexity his difficulties spring. He is neither completely gregarious3, like ants and bees, nor completely solitary, like lions and tigers. He is a semigregarious animal. Some of his impulses and desires are social,some are solitary. The social part of his nature appears in the fact that solitary confinement is a very severe form of punishment; the other part appears in love of privacy and unwillingness to speak to strangers. Graham Wallas, in his excellent book Hunan Nature in Politics, points out that men who live in a crowded area such as London develop a defence mechanism of social behavior designed to protect them from an unwelcome excess of human contacts.4 People sitting next to each other in a bus or a suburban train usually do not speak to each other, but if something alarming occurs, such as an air raid or even an unusually thick fog, the strangers at once begin to feel each other to be friends and converse without restraint. This sort of behavior illustrates the oscillation5 between the private and social parts of human nature. It is because we are not completely social that we have need of ethics to suggest purposes, and of moral codes to inculcate6 rules of action. Ants, it seems, have no such need: they behave always as the interests of their community dictate7.

But man, even if he could bring himself to be submissive to public interest as the ant, would not feel complete satisfaction, and would be aware that a part of his nature which seems to him important was being starved. It cannot be said that the solitary part of human nature is less to be valued than the social part. In religious phraseology, the two appear separately in the two commandments of the Gospels to love God and to love our neighbour. For those who no longer believe in God or traditional theology, a certain change of phraseology may be necessary, but not a fundamental change as to ethical values. The mystic, the poet, the artist, and the scientific discoverer are in their inmost being solitary. What they do may be useful to others, and its usefulness may be an encouragement to them, but, in the moments when they are most alive and most completely fulfilling what they feel to be their function, they are not thinking of the rest of mankind but are pursuing a vision.

We must therefore admit two distinct elements in human excellence, one social, the other solitary. An ethic which takes account only of the one, or only of the other, will be incomplete and unsatisfying.

The need of ethics in human affairs arises not only from mans incomplete gregariousness or from his failure to live up to an inner vision; it arises also from another difference between man and other animals. The actions of human beings do not all spring from direct impulse, but are capable of being controlled and directed by conscious purpose. To some slight extent higher animals possess this faculty. A dog will allow his master to hurt him in pulling a thorn out of his foot. K?hlers8 apes did various uninstinctive things in the endeavor to reach bananas. Nevertheless, it remains true even with the higher animals that most of their acts are inspired by direct impulse. This is not true of civilized men. From the moment when he gets out bed in spite of a passionate desire to remain lying down, to the moment when he finds himself alone in the evening, he has few opportunities of acting on impulse except by finding fault with underlings and choosing the least disagreeable of the foods offered for his midday meal. In all other respects he is guided, not by impulse, but by deliberate purpose. What he does, he does, not because the act is pleasant, but because he hopes that it will bring him money or some other reward. It is because of this power of acting with a view to a desired end that ethics and moral rules are effective, since they suggest, on the other hand, a distinction between good and bad purposes, and on the other hand, a distinction between legitimate and illegitimate means of achieving purposes. But it is easy in dealing with civilized men to lay too much stress on conscious purpose and too little on the importance of spontaneous impulse. The moralist is tempted to ignore the claims of human nature, and if he does so, it is likely that nature will ignore the claims of the moralist.

Ethics, though primarily individual even when it deals with duty with others, is faced with its most difficult problems when it comes to consider social groups. Wisdom as regards the action of social groups requires a scientific study of human nature in society, if we are to be able to judge what is possible and what impossible. The first thing is to be clear as to the important motives the behavior of individuals and groups. Of these the most imperative are those concerned with survival, such as food and shelter and clothing and reproduction.9 But, when these are secure, other motives become immensely strong. Of these, acquisitiveness10, rivalry, vanity, and love of power are the most important. Most of the political actions of groups and their leaders can be traced to these four motives, together with what is necessary for survival.

Every human being, after the first few days of his lives, is the product of two factors: on the one hand, there is his congenial endowment;11 on the other hand, there is the effect of environment, including education. There have been endless controversies as to the relative importance of these two factors. Pre-Darwin reformers, in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, attributed almost everything to education; but, since Darwin, there has been a tendency to lay stress on heredity12 as opposed to environment. The controversy, of course, can be only as to the degree of importance of the two factors. Everyone must admit that each plays its part. Without attempting to reach any decision as to the matters in debate, we may assert pretty confidently that the impulses and desires which determine the behavior of an adult depend to an enormous extent upon his education and his opportunities. The importance of this arises through the fact that some impulses, when they exist in two human beings or in two groups of human beings, are such as essentially involve strife, since the satisfaction of the one is incompatible with the satisfaction of the other; while there are other impulses and desires which are such that the satisfaction of one individual or group is a help, or at least not a hindrance, to the satisfaction of the other. The same distinction applies, though in a lesser degree, in an individual life. I may desire to get drunk tonight and to have my faculties at their very best tomorrow morning. These desires get in each others way. Borrowing a term from Leibnizs account of possible worlds,13 we may call two desires or impulses “compossible” when both can be satisfied, and“conflicting” when the satisfaction of the one is incompatible with that of the other. If two men are both candidates for the Presidency of the United States, one of them must be disappointed. But if both men wish to become rich, the one by growing cotton and the other by manufacturing cotton cloth, there is no reason why both should not succeed. It is obvious that a world in which the aims of different individuals or groups are compossible is likely to be happier than one in which they are conflicting. It follows that it should be part of a wise social system to encourage compossible purposes, and discourage conflicting ones, by means of education and social systems designed to this end.

The central group of facts of which a political theory must take account is concerned with the character of social groups. There are various ways in which groups may differ. Among these, the most important are: cause of cohesion, purpose, size, intensity of the control of the group over the individual, and form of government. This leads to the question of power and its concentration or diffusion, which is perhaps the most important in the whole theory of politics. The difficulty of the question arises from the fact that there are technical reasons for concentrating power, but that those who have power are almost secure to abuse it. Democracy is an attempt to solve this problem, but is not always a successful attempt.

A number of problems of great complexity arise from the impact of new techniques upon a society whose organization and habits of thought are adapted to an older system. There have been two great revolutions in human history which came about this way. The first was the introduction of agriculture; the second, that of scientific industrialism. In each case the technical advance was a cause of vast human misery. Agriculture introduced serfdom, human sacrifice, and subjection of women, and the despotic empires which succeeded each other from the first Egyptian dynasty to the fall of Rome.14 The evils resulting from the intrusion of scientific technique are, it is to be feared, only just beginning. The greatest of them is the intensification of war, but there are many others. Exhaustion of natural resources, destruction of individual initiative by governments, control over mens minds by central organs of education and propaganda, are some of the major evils which appear to be on the increase as a result of the impact of science upon minds suited by tradition to an earlier kind of world. Modern science and technique have enhanced the powers of rulers, and have made it possible, as never before, to create whole societies on a plan conceived in some mans head. This possibility has led to an intoxication15 with love of system, and in this intoxication, the elementary claims of the individual are forgotten. To find a way of doing justice to these claims is one of the major problems of our time.

The world in which we found ourselves is one where great hopes and appalling fears are equally justified by the possibilities. The fears are very generally felt, and are tending to produce a world of listless gloom.16 The hopes, since they involve imagination and courage, are less vivid in most mens minds. It is only because they are not vivid that they seem utopian. Only a kind of mental laziness stands in the way. If this can be overcome, mankind has a new happiness within its grasp.

观察人类的生命可以有多种不同的方式。可以把人类视为哺乳动物的一个物种,纯粹从生物学角度加以研究。从这种视点出发,他的成功是无与伦比的。他可以生活在任何气候下,生活在世界上任何一个有水源的地区。他的数量一直在增长,现在则增长得更快了。他的成功得益于把他和其他动物区别开来的一些事物:说话,火,农业,书写,工具,还有大规模的合作。

正是在合作这一点上,他没有能够取得十全十美的成功。人类和其他动物一样,充满了各种冲动和激情,总体来说,这些有助于人类在演化的过程中生存下去。可是,人类的智慧也使其明白,激情经常会造成事与愿违,如果收敛自己的某些激情而发展另一些激情,那么他的欲望可以得到更大的满足,他的幸福可以更加完满。在大部分时间和大部分地点,人类并没有把自己视为一个和其他物种互相竞争的物种。他感兴趣的,不是单个的人,而是人群;人群又被划分为泾渭分明的敌友阵营。有时候,这种划分对于竞争的胜利者很有用,比如白人和红种印第安人之间的冲突。可是,随着智慧和发明增加了社会组织的复杂性,合作的益处持续增大,竞争的益处持续减小。因为智慧和冲动互相冲突,所以伦理学和道德规范对人类而言不可或缺。如果只有智慧,或者只有冲动,那就不会有伦理学存在的空间。

人们为激情所支配,任性妄为,且相当疯狂。借着那股疯狂劲儿,他们把灾难强加到自己和他人身上,这些灾难可能规模巨大。可是,尽管容易冲动的生活是危险的,如果人类不想活得没滋没味,就必须保留冲动的本能。在冲动和控制的两极之间,伦理学必须找到一个平衡点,才能使人们过上幸福生活。正是这种源于人性最深处的冲突,催生了对于伦理学的需求。

就冲动和欲望而言,人类比其他任何动物都要复杂,这种复杂性给人带来了各种烦难。他既不像蚂蚁和蜜蜂那样完全群居,也不像狮子和老虎一样完全独来独往,而是一种半群居动物。他的有些冲动和欲望是社会性的,另一些则是个体性的。单独禁闭是一种非常严厉的惩罚形式,证明了人类的天性中有着社会性的一面;而人类天性的另外一面,则体现在看重个人隐私,不愿意跟陌生人说话。格雷厄姆·华莱斯在其杰作《政治中的人性》里指出,生活在伦敦之类人口稠密地区的人们发展出一种社会行为的防御机制,使自己避开不胜其扰的人际交往。在公共汽车或者城郊列车里,人们通常挨坐在一起,互不搭话,可是一旦有某种紧急情况发生,比如空袭,甚至是罕见的浓雾,这些陌生人马上就会开始视彼此为朋友,放下矜持交谈起来。这种行为表明,人性在个体性和社会性的两面之间来回摆动。正因为我们不是完全社会性的,所以需要伦理学来告诉我们行为的目的何在,需要道德规范来反复灌输各种行动规则。蚂蚁看来就没有这种需要:支配它们行为的总是群体的利益。

然而人类不一样,即使他能够让自己像蚂蚁一样屈从于公共利益,也不会就此完全满足,还会意识到自己天性中的一部分仍然处于极度饥饿之中,而这个部分看来对他自己非常重要。不可以说,人性的个体性的一面不如社会性的一面有价值。用宗教术语来表述的话,这两面分别对应《福音书》里的两条教义:爱上帝,爱我们的邻居。对于那些不再信仰上帝或者传统神学的人而言,可能有必要对表述方式做些调整,可是其中体现的伦理观却并没有根本性差别。神秘主义者、诗人、艺术家和科学发现者,究其本质,无不是独行客。他们所从事的工作可能让他人受益,这对他们可能是种鼓励,可是,他们在心目中为自己设定好了某种职责,在他们最活跃、最完满地践行这种职责的时刻,并没有为他人着想,而是在追求自己的理想境界。

因此,我们必须承认,人类的卓越品质包含了两个截然不同的要素,一个是社会性,另一个是个体性。任何一种伦理学,如果仅仅考虑其中之一而不及其余,都将是不完整和不尽如人意的。

人类事务对于伦理学的需求,不仅起因于人类的半群居性,或者起因于他无法实现内心的理想境界,还起因于人类和其他动物的另一个区别。人类的行动并非全部起源于直接的冲动,而是能够被有意识的目的所控制和引导。在某种轻微的程度上,高等动物也具备这种能力。狗会允许主人在把它脚掌的刺拔出来的过程中弄痛它自己。克勒的类人猿做出各种各样非本能的动作来努力够到香蕉。尽管如此,有一点始终是千真万确的:即便是高等动物,它们的绝大多数行动仍然是由直接的冲动所激发。文明人却不是这样。一个人,从极力压制继续赖床的强烈欲望、从床上爬起来的那一刻起,到发现自己要独自度过漫漫长夜之时,他很少有机会冲动行事,除非找下属的茬儿,或者对供应给自己的午餐挑挑拣拣。在其他任何方面,指导他的都不是冲动,而是经过慎重思考后決定的目的。他之所以做他所做的事,不是因为这个行动带给他愉悦,而是希望能从中赚到钱,或者得到其他回报。正是因为这种着眼于一个渴望达到的目的而行动的力量,伦理学和道德规范才会起作用,因为它们一方面表明了善的目的与恶的目的之间存在区别,另一方面也表明了为达目的所采取的正当手段和不正当手段截然不同。可是,与文明人打交道很容易过度强调有意识的目的,而漠视心血来潮的冲动的重要性。道德家忍不住忽略人性的各种诉求;如果他这么做,那么人性很可能也会忽略道德家的种种主张。

即使是涉及相对他人的义务,伦理学也主要是针对个人的。尽管如此,当它开始研究社会集团的时候,就会面对最为棘手的问题。关于社会集团的行动明智与否,需要对社会中的人性进行科学的研究,前提是我们能够判断什么是可能的,什么是不可能的。首先要明确支配个人和集团行为的重要动机,其中最为迫切的是那些与生存息息相关的,比如食物、住所、衣服和生育。可是,一旦这些稳稳到手,另一些动机就会变得极其强大,贪欲、好胜、虚荣和权欲就是其中最重要的。各个集团及其领袖的大部分政治行动归根结底就是基于这四种动机,加上对于生存不可或缺的那些动机。

每个人在出生几天以后,都会成为两个因素的产物:一个是自身合宜的先天禀赋,另一个是包括教育在内的环境的影响。这两个因素究竟孰重孰轻,一直争议不断。18世纪和19世纪早期,达尔文之前的改良者几乎把一切都归结为教育;可是,自达尔文伊始,出现了一种趋势,重视遗传性而非环境。当然,这种争议的焦点只是这两个因素究竟哪个更重要一些。无可否认,两者都在发挥作用。尽管我们无意就争论中的各个问题得出任何结论,仍然可以相当有信心地断言,导致一个成人做出某种行为的各种冲动和欲望,在极大程度上取决于他所受到的教育和获得的机遇。这一点的重要性可从以下事实窥见一斑:当有些冲动存在于两个个体或者两个集团当中的时候,基本上处于对立状态,因为满足一个和满足另一个不相容;与此同时也存在其他冲动和欲望,其性质使得满足一个个体或者集团有助于满足其他个体或者集团,或者至少不妨碍后者获得满足。同样的区别也适用于个人生活,只不过程度较轻。我既想今晚大醉一场,又想明早仍旧精神抖擞。这些欲望彼此妨碍。借用莱布尼兹描述“可能世界”的一个术语,当两个欲望或者冲动都可以被满足的时候,我们可以称它们“共同可能”;当满足一个和满足另一个不相容的时候,我们可以称它们“互相冲突”。如果两个人都参加美国总统竞选,那么其中一人必然落选。可是,如果两个人都想致富,一个靠种棉花,另一个生产棉布,那么完全有可能二人都得偿所愿。显然,不同个体或集团有着共同可能的目标的世界,很可能要比他们的目标互相冲突的世界更加幸福。由此可以推断,明智的社会制度应该鼓励共同可能的目的,阻止互相冲突的目的,而要做到这一点,就必须针对这个目标设计教育和社会体制。

政治学理论必须考虑的那些重要事实关注社会集团的性质。集团可能各不相同,其中最重要的区别在于凝聚的原因、目的、规模、集团对个体控制的强度,以及政府的形式。这些会引出权力以及集权或者分权的问题,而这或许就是整个政治学理论中最重要的部分。这个问题很难求解,因为权力集中有技术方面的原因,可是那些拥有权力的人几乎都会滥用权力。民主制度尝试解决这个问题,可是实情往往并不盡如人意。

新技术对社会产生影响,引发大量极其复杂的问题,尤其是当这个社会的组织方式和思想习惯还在按照旧体制的那套运行。人类历史上有两次大变革便是如此,第一次是农业的诞生,第二次是科学工业主义的诞生。每一次变革,技术进步都给人类带来了巨大的不幸。农业引进了农奴制、活人祭、男尊女卑,还有从第一个古埃及王朝开始到罗马帝国灭亡期间此起彼伏的专制帝国。科学技术入侵所造成的种种恶果,恐怕才刚刚拉开序幕。其中最大的恶果就是导致战争升级,可是还有很多其他的恶果,主要包括对自然资源的竭泽而渔,政府对个人自主权的毁灭,通过教育和宣传等核心部门控制人的思想。由于科学对因循守旧的人类思维施加影响,这些恶果看起来不断扩大。现代科技让统治者拥有了更多的权力,使得根据某人头脑里的构想来创造整体社会成为可能。这种可能性导致人们沉迷于体制而不能自拔,忘却了个体的基本诉求。寻找一种公正的方式处理这些诉求,是我们这个时代的主要问题之一。

在我们身处的这个世界,巨大的希望或可怕的恐惧有着同样的可能性。恐惧会在人群当中蔓延,很容易让世界变得沉闷阴郁。而希望呢,因为需要想象力和勇气,所以在大多数人的头脑中并没有那么生动,就是因为不够生动,所以看起来好像是乌托邦。某种思想的懒惰成为唯一的拦路虎。如果可以克服这一点,一种崭新的幸福对人类而言将是触手可及的。

1. minister to: 给予援助。

2. diminution: 减少,缩小。

3. gregarious:(动物)群居的,(人)爱社交的。

4. Graham Wallas: 格雷厄姆·华莱斯(1858—1932),英国教育家和政治学家,倡导用实验的方法研究人的行为;defence mechanism: 防御机制,指人类自我用来对抗其所察觉到的危险并保护自身的心理过程,也指在这一过程中所运用的技巧。这个过程通常是无意识的。

5. oscillation: 摆动。

6. inculcate: 反复灌输。

7. dictate: 命令,规定。

8. K?hler: 克勒(1887—1967),德国心理学家、格式塔心理学派创始人之一,通过实验发现黑猩猩具有设计和应用简单工具、建立简单结构的能力,著有《类人猿的智力》等。

9. imperative: 极为重要的,紧急的;reproduction:生育,繁衍。

10. acquisitiveness: 贪婪攫取。

11. congenial: 合意的,相宜的;endowment: 天资,天赋。

12. heredity: 遗传(性)。

13. Leibniz: 莱布尼兹(1646—1716),德国自然科学家、哲学家、数学家;possible world:可能世界,运用此概念的理论家认为,实际世界是很多可能世界中的一个。

14. serfdom: 农奴制;subjection:征服,强行统治;despotic: 专制的,暴虐的。

15. intoxication: 陶醉,极度兴奋。

16. listless: 倦怠的,无精打采的;gloom:忧郁,阴暗。