理解别人?不可能的

2018-01-05ByKantaDihal

By Kanta Dihal

I am a literature scholar. Over thousands of years of literary history, authors have tried and failed to convey an understanding of Others. Writing fiction is an exercise that stretches an authors imagination to its limits. And fiction shows us, again and again, that our capacity to imagine other minds is extremely limited.

It took feminism and postcolonialism to point out that writers were systematically misrepresenting characters who werent like them. Male authors, it seems, still struggle to present convincing female characters a lot of the time. The same problem surfaces1 again when writers try to introduce a figure with a different ethnicity to their own, and fail spectacularly.

I mean, “coffee-coloured skin”? Do I really need to find out how much milk you take in the morning to know the ethnicity2 you have in mind? Writers who keep banging on with food metaphors to describe darker pigmentation show that they dont appreciate what its like to inhabit such skin, nor to have such metaphors applied to it.3

英文中有一個表达,叫put yourself in others shoes,意为把自己假想为他人,或者设身处地地为他人着想。这说来容易,可是要真的做到却很难。小说家一向以擅长想象、理解人性著称,如果他们对角色的理解都流于表面的话,那就更别提让普通人去理解别人了。

Conversely, we recently learnt that some publishers rejected the Korean-American author Leonard Changs novel The Lockpicker (2017)—for failing to cater to white readerslack of understanding of Korean-Americans.4 Chang gave“none of the details that separate Korean-Americans from the rest of us,” one publishers letter said. “For example, in the scene when she looks into the mirror, you dont show how she sees her slanted5 eyes…” Any failure to understand a nonwhite character, it seems, was the fault of the nonwhite author.

Fiction shows us that nonhuman minds are equally beyond our grasp. Science fiction provides a massive range of the most fanciful depictions of interstellar space travel and communication—but anthropomorphism is rife.6 Extraterrestrial intelligent life is imagined as Little Green Men(or Little Yellow or Red Men when the author wants to make a particularly crude point about 20th-century geopolitics).7 Thus alien minds have been subject to the same projections and assumptions that authors have applied to human characters,8 when they fundamentally differ from the authors themselves.

For instance, lets look at a meeting of human minds and alien minds. The Chinese science fiction author Liu Cixin is best known for his trilogy9 starting with The Three-Body Problem(2008). It appeared in English in 2014 and, in that edition, each book has footnotes—because there are some concepts that are simply not translatable from Chinese into English, and English readers need these footnotes to understand what motivates the characters. But there are also aliens in this trilogy. From a different solar system. Yet their motivations dont need footnoting in translation.

Splendid as the trilogy is, I find that very curious. There is a linguistic-cultural barrier that prevents an understanding of the novel itself, on this planet. Imagine how many footnotes wed need to really grapple with10 the motivations of extraterrestrial minds.

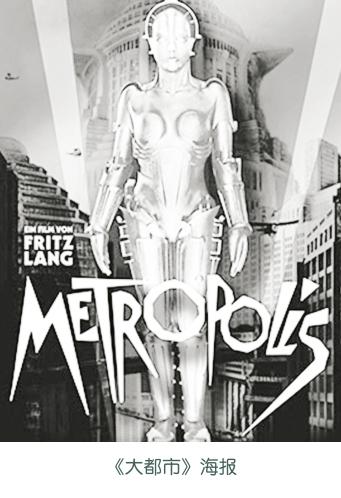

Our imaginings of artificial intelligence are similarly dominated by anthropomorphic fantasies. The most common depiction of AI conflates11 it with robots. AIs are metal men. And it doesnt matter whether the press is reporting on swarm robots invented in Bristol or a report produced by the House of Lords: The press shall plaster their coverage with Terminator imagery.12 Unless the men imagining these intelligent robots want to have sex with them, in which case theyre metal women with boobily breasting metal cleavage—a trend spanning the filmic arts from Fritz Langs Metropolis (1927) to the contemporary TV series Westworld(2016).13 The way that we imagine nonhumans in fiction reflects how little we, as humans, really get each other.

All this supports the idea that embodiment14 is central to the way we understand one another. The ridiculous situations in which authors miss the mark stem from the difference between the authors own body and that of the character. Its hard to imagine what its like to be someone else if we cant feel it. So, much as I enjoyed seeing a woman in high heels outrun a T-Rex15 in Jurassic World (2015), I knew that the person who came up with that scene clearly has no conception of what its like to inhabit a female body, be it human or Tyrannosaurus.

Because stories can teach compassion and empathy, some people argue that we should let AIs read fiction in order to help them understand humans.16 But I disagree with the idea that compassion and empathy are based on a deep insight17 into other minds. Sure, some fiction attempts to get us to understand one another. But we dont need any more than a glimpse of what its like to be someone else in order to empathise with them—and, hopefully, to not want to kill and destroy them.

As the US philosopher Thomas Nagel claimed in 1974, a human cant know what it is like to be a bat, because they are fundamentally alien creatures: Their sensory apparatus and their movements are utterly different from ours.18 But we can imagine“segments19,” as Nagel wrote. This means that, despite our lack of understanding of bat minds, we can find ways to keep a bat from harm, or even nurse and raise an orphaned baby bat, as videos on the internet will show you.

The problem is that sometimes we dont realise this segment of just a glimpse of something bigger. We dont realise until a woman, a person of colour, or a dinosaur finds a way to point out the limits of our imagination, and the limits of our understanding. As long as other human minds are beyond our understanding, nonhuman ones certainly are, too.

我是研究文学的。几千年的文学史,作者无一不想达成对他人的理解,却从未成功过。写小说是一种把作者的想象力发挥到极致的训练,然而其结果还是一再向我们表明,我们想象他人的能力其实相当受限。

女性主义和后殖民主义理论认为,作者在写与自身迥异的角色时,常常习惯性地歪曲他们。男性作家似乎多少年以来一直挣扎于写出令人信服的女性角色;同样的问题也出现在当作家尝试引入一个与自己不同种族的角色时,也容易败得很惨。

比如,“咖啡色的皮肤”?要想知道你究竟说的是哪种肤色,我还得知道你早上喝咖啡加多少奶不成?如果作家总爱用食物的颜色来比喻深肤色的人,说明他们既非真心欣赏这些肤色,也找不到合适的比喻去形容。

与此不同的是,我们最近听说,一些出版商拒绝了韩裔美国作家伦纳德·张的小说《开锁人》(2017),竟然是因为作者没能照顾到对韩裔美国人缺乏了解的白人读者。一位出版商在拒信中说,张“没能给出任何可以将韩裔美国人跟我们其他人区分开来的细节。比如说,有一幕她在照镜子,可是你却没写她看见自己眼睛有点斜……”似乎如果读者理解不了白人以外的角色,都得怪罪到那位非白人的作者身上。

从小说中也能看出,我们同样无法把握非人类生物的心理活动。科幻小说提供了大量关于星际旅行和太空对话的描写,尽管天马行空,但是对外星生物的人格化依然是主流。外星生物被想象成小绿人(也有可能是小黄人或者小红人,就算是作者对20世纪的地缘政治最为粗糙的反映了)。因此尽管外星人跟人类有着本质的不同,他们在预期和假想时,却被作者赋予了跟人类有着相同的心理运作模式。

例如,让我们来看一场人类和外星人的心灵碰撞。刘慈欣,中国科幻小说作家,以2008年的《三体》为首的三部曲闻名。在其2014年的英文版中,每本书都有脚注,因为有些概念没法直接从中文翻译为英文,英文读者需要靠脚注来弄懂人物的动机。可是三部曲中也有来自不同星系的外星人,而他们的动机则不需要靠脚注来解释。

所以这套书好归好,但让我很是疑惑。在这个星球上,我们要理解这本书,都有那么多的语言文化障碍。那么要是想真正弄懂外星生物,该需要多少脚注啊。

我们对人工智能的理解差不多也是受控于对其人格化的想象。描述人工智能时,普遍都将其与机器人混为一谈。仿佛人工智能就是金属做的人。不管是媒体报道布里斯托尔市发明的大批机器人,还是上议院发布的报告,都无一例外地用《终结者》里的机器人形象配图。除非人类想象这些智能机器人想和人类发生性关系,才会有丰乳肥臀的女机器人设计出来——这样的形象在电影里屡次出现,早至1927年弗里茨·朗格导演的《大都市》,近至2016年的电视剧《西部世界》。我们在艺术作品中对非人类的想象,折射出了我们作为人类,对彼此的真正了解是多么少。

所有这些都证明,我们理解他人,最主要靠的是设身处地。作者之所以描述得不准确,造成了滑稽的局面,主要是因为作者自身和其角色之间存在差异。如果没法切身去感受,很难想象成为别人会是什么感觉。所以,尽管我也很爱看《侏罗纪世界》里穿高跟鞋的女人跑在了霸王龙前面,我依然知道,想出这一幕的人显然并不明白拥有女性身体是什么感觉,不管是人,还是恐龙。

因为小说可以使人增进同情与理解,有的人就说应该让人工智能来阅读小说,以使他们理解人类。但我不认为理解和同情是基于对他人的深刻了解。毋庸置疑,很多小说试图让我们去理解他人。但是,要想理解别人,未必非得设身处地,更不用靠设身处地,来抑制我们有时生出的想伤害别人的心。

美国哲学家托马斯·内格尔1974年称,人无法了解蝙蝠,因为人和蝙蝠根本就是两种完全不同的生物,蝙蝠的感觉器官和运动器官与人类的完全不同。但是我们却可以想象“部分”,内格尔写道。也就是说,尽管我们对蝙蝠的思想缺乏了解,但我们依然可以设法保护它们不受伤害,甚至像网上的那些视频教你的那样,哺育一只失去双亲的小蝙蝠。

问题在于,有时我们没法意识到这个更大的整体中所谓的部分究竟在哪里。除非有一位女性、一个不同肤色的人,或者一只恐龙,能够指出我们想象力和理解力的不足,否则我们无法知道自己假想错了。其他的人我们尚且无法了解,更别说非人类的生物了。

1. surface: 浮出水面,显露。

2. ethnicity: 种族。

3. bang on: 喋喋不休,说个没完;pigmentation:(生物的)天然颜色;metaphor: 隐喻,暗喻。

4. conversely: 相反地,反过来地;cater to: 迎合,满足。

5. slanted: 倾斜的,歪斜的。

6. interstellar: 星際的;anthropomorphism:拟人化,人格化;rife: 盛行的,普遍的。

7. extraterrestrial: 地球外的,天外的;crude:粗糙的,简陋的;geopolitics: 地缘政治学。

8. be suject to: 经受,遭受; projection: 预测,推测; assumption: 假设,臆断。

9. trilogy: 三部曲。

10. grapple with: 尽力解决,设法对付。

11. conflate: 合并,混合。

12. plaster: 贴满;Terminator: 《终结者》,美国著名科幻系列电影。

13. cleavage: 乳沟;span: 持续,跨越;Fritz Lang: 弗里茨·朗格(1890—1976),奥地利导演。

14. embodiment: 化身。

15. T-Rex: 霸王龙,后文Tyrannosaurus是其属名。

16. compassion: 同情,怜悯;empathy: 同情,共鸣。

17. insight: 洞察力,深刻见解。

18. Thomas Nagel: 托马斯·内格尔(1937— ),当代知名哲学家;apparatus: 设备,装置。

19. segment: 部分。

阅读感评

∷秋叶 评

从这个标题,我猛然联想到“诗不可译”的说法,但奇怪的是,提出“诗不可译”的人,往往都是诗歌的译者,他们显然是“知其不可译而译之”!选文作者自称是文学研究专家,应该至少对于西方传统里的文学作品较为熟悉(当然也未必,当代语言学家往往不去掌握多门语言,同样,文学专家有时也不屑去读小说、诗歌、戏剧),但她居然用一句话去概括世界文学中的人物塑造,并推而广之于全人类的“困境”:“我们能理解他人吗?小说表明,这不可能!”作者进而断言,在数千年的文学史进程中,作家们曾努力尝试着去理解“他者”(应该指作品中的人物角色),但均以失败告终。最能发挥作家们想象力的小说创作的历史表明,我们想象他人(心态)的能力极其有限。接着,作者指出,尤其在塑造异性角色与其他种族的人物(西方文学中确实常把女性与异族统称为“The Other”)时,作家们总是习惯性地予以歪曲(systematically misrepresenting)并以惨败收场(fail spectacularly)。

真是这样吗?如果我们不是以目前非常时髦的文化理论的概念出发,而是以文学史上的具体文学创作出发,恐怕会有非常不同的结论。在西方文学史上,有许多男性作家塑造的女性角色,以其逼真的形象,给读者留下了难以磨灭的印象。其中一个典型例证是英国作家哈代笔下的苔丝,尤其是小说的第58章。此时,追捕她的人正在跟踪搜索,她知道同自己深爱的克莱尔在一起的时日已经无多,但她并不慌乱,同克莱尔商量自己死后的安排,并将妹妹的终身郑重托付给他。追捕者到了,她还在史前巨石阵的一块石板上酣睡……从哈代笔下的这位弱女子身上,我们既可看到勤劳、勇敢、朴实、善良等美好品质,又能感觉到其冲破维多利亚时代旧礼教束缚的叛逆精神之光。同样在英国文学中,福斯特(E. M. Forster)的名作《印度之行》既描写了两位英国女性阿德拉和穆尔夫人,又描写了一位印度人阿齐斯,整个小说的背景设在受英国殖民统治的印度,探讨的是英国人和印度人之间建立和谐关系的可能性的主题。作者在20世纪前20年曾两度访问印度,并与在印英国人和印度本地人接触,这些都使他在小说中所刻画的人物——不管是英国人还是印度人——入木三分,其逼真性不仅打动了英国读者,还让一位印度女作家在印度摆脱英国殖民统治独立后的1960年初,把这部作品改编成剧本在印度演出!其实,作家在小说中不管是刻画异性还是描绘异族(西方自文艺复兴时代以来即有异国风情文学的传统,其中不乏名篇巨制),在中外文学史上占据经典地位乃至在普通读者中引起巨大共鸣的例子,不胜枚举。我想,这些作品取得成功并受到读者的欢迎,一定是归因于其高度的逼真性与作者丰富的想象力,而非基于流于表面甚至歪曲的角色建构!

不过,这种认为对于“他者(The Other)”理解的不可能并非空穴来风。西方自上世紀70年代以来的解构理论,尤其是随后的女权主义、后殖民主义和新历史主义解读文学作品,都有一个基本的假设,即认为传统意义上的文学都代表了精英权贵的意识,表现出父权宗法制度或压制性政权的价值观,并与之有共谋关系。于是,连同这些文学创作者所塑造的人物以及其中所表达的理性观念,诸如话语表达现实、不同文化种族之间的有效沟通,等等,都值得怀疑,甚至应当予以彻底的否定与批判。因此,原文作者所持的这种“人类——尤其是人类中的‘他者——之间无法相互理解”“以小说为代表的文学作品表明作家总是在歪曲所塑角色”等观点就不足为怪了。

然而,尽管当前的理论氛围总是抱着思想与文化的相对主义,一味强调人类尤其是不同性别与种族的性格与文化之间的差异,总认为人人(individuals)——尤其是男女以及异族之间,其特性与文化均属独特无比,无法通约,但我想,只要我们在此方面的理性知识与人生阅历积累到一定程度,就不会轻言性别与种族的绝对独特性,更不会断言他们之间毫无共通之处,以至于作出他们永远不可能相互理解的结论。其实,不管是性别、种族还是文化,它们之间必然是既有差异,又有相似或类同,“同”与“异”往往只是程度之差,而非毫不相干的绝对两极,否则近些年来颇为流行的“跨文化交际”或“跨文化研究”等领域就没有其存在的必要性了,“人类命运共同体”也更无从谈起。其实早在19世纪,德国理论家赫尔德(Johann G. Herder)就十分强调移情(empathy)的作用,认为人们通过移情,可以设身处地去想象他人的境况,也就是可以超越差异而达到相互理解。到了20世纪下半叶,德国著名哲学家哈贝马斯(Jurgen Habermus)也提出了人类之间“互为他者”的可能性。近些年来,我们在批判所谓的“欧洲(西方)中心主义”的同时,也在呼吁需要建立一种“同情的理解(sympathetic understanding)”,即要求我们把自己的主观感情自觉地向所关注的客体投射,尽量去体验他人的境况,以最终达到相互理解的愿望。这就是说,“我”与“他者”之间,甚至人类不同种族之间的感情是可以相通的,只要你能自觉地去靠近并主动予以叩击,就不会有什么不可逾越的“根本性他者(radical alterity)”,共鸣是完全可以产生的!