氛围、场景与学习空间浅析

2018-01-03纳德特拉尼

纳德·特拉尼

氛围、场景与学习空间浅析

Ambiance, Mise en Scène, and the Space of Learning: An Abbreviated Account

纳德·特拉尼

Nader Tehrani

绪言

院校理念与其所进行学习的空间——架构——之间的关系包含着一部鲜活的历史 ,因为它引发了一个理论困境,这个困境根植于一个经久不衰的建筑辩论的核心:即,形式与内容以何种形式对话,是结盟、分离还是勉强契合。教学方法是否以某种方式从其所处的建筑物中产生?建筑物是否为某些教学方法搭建了舞台?

将结构主义学派提出的教学方法与语言学类比,能指(形式)与所指(内容)之间的关系是假定的。因此,两者之间的宽泛契合为文化差异留有余地,这就使得诸如“cat”和“chat”之类的不同单词可以指同一种毛茸茸的动物,而两个不同语种中的相同单词,如法语中的“chat”和英语中的“chat”,可能是指完全不同的事物。同理,随着历史潮流的变化,建筑形式所代表的含义也随着时代的变迁有所不同。一年之前提及“白宫”可能具有完全不同的意味——依当时美国政府的管理实践、管理哲学和贡献而定——这是一个简单的例子,因为当时的政府与现任总统的班底迥然不同。然而,作为一座建筑物来说,白宫无论在形式上,还是空间或材料上都没有任何变化。

当然,作为建筑师,我们希望自己的设计是有意义的,没有什么比“我们所做的东西充满了假定性、不精确或不可控制”更加令人不安的想法, 为此,建筑师制定了详尽的规范来确保设计的精准度。尽管如此,正是创作理念和作品认可度之间的不一致,在很大程度上扩大了思想和物质世界间的隔阂。当马格里特(Magritte René)写出“这不是一个烟斗”(Ceci n'est pas une pipe)时,这句话作为宣言毫无争议,但是在表象背后,它就成了建筑师时常面临的一个并不客观的文化符号。1)当然,语言上的类比到此为止,毕竟建筑物通过感官、认知和体验,以各种各样的方式与人类主体相互作用。因此,作为建筑师,我们的设计不仅仅是对现状的反映,还具有影响并改变我们所生活的世界的可能,离开了这种责任,任何用理论来解释我们所作所为的尝试都是徒劳。2)

有趣的是,尽管某些机构的管理层和管理思想发生了变化,但其建筑物却成了具有某种精神特质的同义词。为此,机构、规则和物质的基本结构往往会产生某种经久不衰的联系,从而衍生出一种不依赖领军人物来推动发展的经验传承模式。建筑形式的延续和形式背后知识文化的暂时性断层,这两者间的对峙正是这场难以调和的争论的核心。

选择性教学方法

有一些显而易见的例子,建筑师在论证时经常引用。对3所耳熟能详的院校——英国伦敦建筑联盟学院(AA学院)、哈佛大学设计学院和库伯联盟学院进行简略对比,可能有助于缓解紧张的局面,因为每所院校的重要领导人——不论是院长还是系主任——都在各自的院校中发挥作用,同时也带来了在辨证教学方法、文化及行政管理层面更有意义的改变。

建筑联盟学院

1971年,曾作为建筑联盟学院所在地的贝德福德广场配对排屋为营造空间亲密性提供了可能,其作为绅士俱乐部的特征被保留下来,而阿尔文·博雅斯基将其继承后用作学校,是保持其独立和小巧?还是融入帝国理工学院成为其众多院系之一?是他面临的重大历史挑战。博雅斯基第一次与“恶意收购”争取独立的斗争是勇敢无畏的;然而,这场斗争还是使其失去了政府补贴。这是博雅斯基作出这个有悖于英国统治阶层以及投资人心意的决定而不得不付出的代价。出于这个原因,AA学院进行了办学理念的重塑,这是一个使其具备财政偿还能力的实用战略:只有向能经受国际竞争的一流建筑院校看齐,才能拥有财政上的话语权。3)

从建筑学角度来看,尽管这些排屋因地处伦敦中心而尊贵显赫,而且内饰“高雅”,但它们并不需要太多加工。AA学院空间的大部分均与贝德福德广场排屋典型的端庄布局一致,但是不具备容纳众多人听课和参加开幕式的空间。因此,AA学院的规划布局也呈现了一些出于急切需求不得已而为之的建筑巧思。例如,大礼堂的造型无法与排屋的横向线条相协调,因此不得不切断大部分墙面,跨越两排房屋的宽度,使其能够容纳更多人——而这并非其创意初衷。为了利用一排房屋内的辅助空间容纳更多观众席位,大礼堂的屏幕以45o角呈现在观众面前,形成一个L形,营造出两个独立空间内的两组观众关注一个焦点的效果。排屋内其他空间也被巧妙地用来调解其现实的局限性,成为促进变革的催化剂。其中最突出的是位于报告厅和画廊上方二层建筑物核心、与图书馆相邻的吧台。毋庸赘言,这是颇具争议的空间,是它引发了那个时代最广泛的争论。不知是酒精还是吧台的镜子营造出了非正式的演讲氛围,在这里,学术争论的意义没有排屋这个能够灵活将住宅结构转变为具有国际影响力的学院的事实重要。该空间结构和建筑实体证明,它们不需要定制形式来适应所谓的功能。

除此之外,是阿尔文·博雅斯基的领导使AA学院至今仍名闻遐迩,尽管它已更换了3任领导,但各具优点。面对即将倒闭的紧迫威胁,博雅斯基意识到,他需要一种完全不同的财政模式和教学策略来解决其基础设施天性小巧的问题。转型的关键是吸引大量留学生来垫付学费,同时,将工作单元转变为达尔文工作室,教员的收入取决于学生助学金的普及。虽然博雅斯基在学校决定上说一不二,但他也巧妙地利用工作单元的形式来鼓励下一代年轻建筑师发表见解。

博雅斯基还给这所学校带来一种意识,为了让一个声音存在,就必须让人们听到这个声音。而要在排屋里做到这一点的唯一方法,就是通过媒体获得超越时代的影响力和超越国界的事件来放大信息。通过AA学院刊物的加倍努力,旋转演讲厅和旋转展示空间具有了不同的影响力,其权威性甚至超越了教学区域,起到了指导其他院系(不仅仅是学生)的作用。博雅斯基本人并不具有建筑实践经验,正因如此,他不需要通过自己的设计来说话,他的实践就是管理。在他作出的决策中,出现了辩论、争执和讨论,而这些最终产生了使之闻名的实践:假如没有博雅斯基的信任和授权,库哈斯、屈米和哈迪德会何去何从?博雅斯基1990年就去世了,随之而逝的是一个时代,一个在具有特殊意义的历史建筑的背景下斡旋领导挑战的时代;可以说,其适应性再利用,是基于前文的宽泛契合而形成的,即使有排屋的扩建、专业工作室的引进、以及信息在数字化时代的转变,时至今日,这所学校在某种程度上仍秉持这种性格。

哈佛大学设计学院(GSD)

哈佛大学设计学院的冈德楼是由约翰·安德鲁斯设计的,完成于1971年,同一年,博雅斯基出任AA学院院长。虽然新建教学楼是何塞普·路易·塞特钟爱的项目,但由于他在1969年之前就不再担任院长职务,所以再没有机会主持该项目了。可以说,从罗宾逊楼到冈德楼是塞特多年致力于创立“城市设计”学科的结果,这在当时正处于起步阶段。事实上,新项目原本是想开发一座具有开放性和灵活性的建筑,让建筑、城市设计、景观设计和规划可以在多年的分楼教学之后仍能在同一个屋檐下共享一个空间。因此,冈德楼可以说是塞特教学理念的表现,也是最早表现出跨学科交流的空间设计之一。4)

该建筑的金字塔结构在其形态清晰度上是确定无疑的;其阶梯式配置与一系列历史前因有关,但作为工作和协作的空间却是前所未有的。“托盘”位于一座由大跨度桁架所覆盖的纪念厅之上,起到工作室平台的作用,几段楼梯穿插其间,将大平台分解成若干区域,并产生了保障消防安全之外的流线冗余。实际上,这些楼梯提供了大量上下楼的通道,所以成为社交互动的催化剂——或偶尔在必要时隔断成为阻化剂。该楼从底部一个最初设想为休息室的夹层开始增加梯度,高度按年级逐年上升,毕业班位于最高梯级。如果这座建筑让人想起工业生产的车间,那么阶梯式就营造出了将良性的设计理念向剧院空间转化的效果;也就是说,梯级在外观上确实营造出逐级而上的、类似剧院座位的效果,在公共空间内部营造出集体主义精神,创造出作为窥探主体和客体的个人“存在”感。如果这种解释过于空泛,那也可以明显地被教授和学生通过无数方式内化。虽然某些学生更喜欢梯级“下方”更独立、更具有私密性的空间,但其他学生更喜爱开放的露天剧场。然而,主导空间的设计过程是一种公共活动,建筑话语是一个集体项目,无论是作为学生还是教师,每个人都以某种方式进行重要参与;实际上,通过类比,它已成为大型“评图”空间之一,因为每个学校的目标和理念都从下一个管理者身上体现出来。它提醒我们,同一时期的AA学院是没有专门工作室的,因此大多数学生与“工位搭档”一起去租赁伦敦周边的工作室,创造更多的巴尔干文化,在那里各种小单元作为思想、绘画、着装和类似行为的集合,随后在酒吧呈现出来。反过来说,冈德楼的大尺度呈现了一切,在这里,多学科和个人都有机会彼此融合,相互学习,也可以面对面展开争论,在更加开放的工作室空间中释放差异。不同院校的理念拥有同一把保护伞。

Introduction

The relationship between schools of thought and the spaces of learning within which they occur –their architecture–contains a telling history, because it conjures up a theoretical predicament that lies at the heart of an architectural debate that persists over the ages: that is, how form and content come into dialogue, whether in alignment, in disjunction or a difficult fit. Do pedagogies somehow emerge from the buildings within which they are housed, and do buildings set the stage for certain pedagogies?

For those raised in the Structuralist school of thought, the linguistic analogy holds that the relationship between the signifier (form) and signified (content) is arbitrary. As such, the loose fit between the two allows for cultural differences, such that different words such as 'cat' and 'chat' could refer to the same furry creature, while the same word in two different languages, 'chat' in French and 'chat' in English, can mean completely different things. In a similar way, forms of buildings have come to represent different things over the ages, as meanings transform with the changes in historical tide. A reference to the "White House" would come to signify something completely different a year ago, based on the practices, philosophy and contributions of the administration of that time – an easy example given the radical disparity in evidence as compared to the current presidency. And yet, the White House as a piece of architecture may not have changed at all: not in its form, nor spaces or materials.

Of course, as architects, we like to think that what we design matters, and so nothing can be more disconcerting than the idea that what we do is arbitrary, imprecise, or uncontrollable given the depth of specification we bring to its discipline. Notwithstanding, it is this disjunction between theories of production and the reception of works that, in great part, drives the schism between the world of ideas and objects. When Magritte wrote "ceci n'est pas une pipe", we know it was not controversial as a proclamation alone, but in the context of the image that floated above it, it became a scandalous meme of the very predicament we constantly confront as architects.1)Of course, the linguistic analogy only goes so far, as architecture interacts with the human subject in a myriad of ways, among other things, through the senses, their cognition, and the advent of experience. As such, as architects, we like to think that what we design is not merely a reflection of the status quo, but in fact has the agency to impact and transform the world we live in, without which any attempt at giving theoretical body to what we do would be impotent.2)

What is interesting, then, is how the architecture of certain institutions becomes synonymous with a certain ethos despite the changes in administration and thinking. To this end, the underlying structures of organization, program and materiality often produce conditions that make certain associations persist over time, such that it produces an institutional memory that does not merely depend on the human protagonists that drive them. The tension that is produced between the persistence of architectural form on the one hand, and the temporal discontinuity of the intellectual cultures that are housed within these forms, on the other hand, is at the heart of this argument, and may be something that cannot be reconciled.

A Selective Pedagogical Auto-Biography

There are obvious examples to which architects commonly refer to help shape this argument. A brief comparison between three familiar schools, the Architectural Association, the Harvard Graduate School of Design and the Cooper Union may help to frame these tensions. Key protagonists within each institution – whether deans or directors– worked within the spatial construct of their respective schools to amplify their cultures, while also bringing in the critical pedagogical, cultural and administrative changes of their time.

The Architectural Association

In 1971, the paired-up row houses on Bedford Square that gave space to the Architectural Association produced the intimacy of a space that substantiated its character as a Gentleman's club, what Alvin Boyarsky inherited as the school faced a critical historical challenge: to stay independent and small, or to become subsumed under the Imperial College, becoming one of its many departments. As a first act, Boyarsky's fight for independence from 'hostile takeover' was courageous; yet, it did not save it from the loss of public subsidies, the price he had to pay for making a decision that did not sit well with the British Establishment and those who controlled its purse strings. For this reason, one might read into the re-conceptualization of the AA, a practical strategy to make it fiscally solvent: and what made it float financially needed to be aligned with an intellectual construct that could withstand the international competition of its time.3)

1 建筑联盟学院广场/Square of Architectural Association (摄影/Photo: 于博柔)

2 建筑联盟学院吧台/AA bar (图片来源/Source: http://life.aaschool.ac.uk/?m=201408)

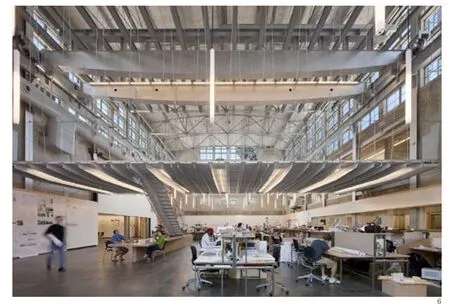

3 哈佛大学设计学院内景/Interior view of Harvard Graduate School of Design(图片版权/Courtesy: Harvard University Graduate School of Design)

From an architectural point of view, the row houses were not much to work with, notwithstanding the nobility of their address in the heart of London and the 'elegance' of their interiors. For the most part, the spaces of the AA conformed to the typological layout of the row houses of Bedford Square, dignified, but not with the kind of spaces that afforded the volume of people that gathered for its lectures and openings. As such, the programmatic arrangement of the AA also displayed its moments of architectural ingenuity, if only out of dire need. For instance, its auditorium unable to fit within the striated constraints of a row house, had to cut across the grain of the party walls to traverse the width of two row houses to enable a larger public presence – and this is not even its moment of invention. The screen of the auditorium was displayed at 45 degrees to the audience in order to take advantage of a secondary space within one of the row houses to seat more people – making for an L-configuration, and creating two audiences in separate spaces with one focal point. Other spaces within the row houses were also adopted strategically to mediate between the practical realities of their limitations with the opportunities they offered as catalysts for change. Of them all, the bar sat at the core of the buildings on the second floor, atop the lecture hall and gallery, next to the library. Needless to say, this was the space most known and talked about, as it gave rise to the debates of its time. Whether it was the alcohol, or the mirrors of the bar that gave it the ambience for the informality of discourse, intellectual friction and polemical challenges matters less here than the fact that the row house as a type could gain the kind of flexibility and resilience to transform from a residential structure to an institution of international presence. The spatial and physical organization of the structures demonstrate that they do not require the kind of customization of form to fit the so-called function.

从管理和知识的角度来看,1969-1980年是GSD的一段低潮。莫里斯·基尔布里奇是哈佛商学院的数学教授,他被颇有争议地任命为新院长,学院获得了一位对设计的理解极为有限的管理者。基尔布里奇是一名经济学家,其专长是将分析技术用于城市问题,因此减少了对形式、空间和材料等属于建筑教育一部分的研究投入。虽然在基尔布里奇监督下,的确将财政困境扭转,达到了良性财政平衡,但由于缺乏知识型领导能力并且缺少与核心受众的联系,他失去了广大师生的支持和信任。这一历史事件在时间方面是具有讽刺意味的,引起争论的建筑与将空间组织纳入到更大教学计划中的领导人不能一概而论;相反,很多师生对剧院的形式很有异议,导致了院长的最终下台。5)

4 库伯联盟学院预科楼内景改造/The Cooper Union Foundation Building interior renovation, 1971-1974(摄影/Photo: Judith Turner)

1980年,随着杰拉尔德·麦丘被聘为院长,哈里·科布被聘为建筑系主任,该建筑终于获得了其剧院创意应得的领导地位。哈里·科布发表的演讲“我的立场”围绕着他希望本校以什么为核心概述了一系列原则:建筑对城市的承诺、结构秩序与项目的一致性、严谨的评估、在必要的意识形态争论中能够引起并而激发各种实践的开放性,最后是具备大胆无畏的精神:去冒险、去经历失败、去挑战。作为一名职业建筑师,科布50多岁的时候在一个非常成功的合伙关系中建立了自己杰出设计师的声望;汉考克大厦和达拉斯中心等建筑在他被任命为系主任的前几年刚刚建成,发现了将公司委员会的任务转变为更具建设性投机目的的契机,将建筑技术推向新的阶段,激化了普通材料的感性效应,从循规蹈矩甚至是平淡无奇中发明创造。不过,虽然采取了以上学术措施,但他的主张仍被视为安全妥当,而非激进。因此,他在开幕辞中公开宣布自己的原则被视为证明自己大胆无畏的举动,学校几乎瞬间就变成了辩论的温床。科布对新聘教师的管理方式不是为了在学院内复制他的实践模式,而是在学校周围产生了爆炸性的混响。随着一些新声音以及对对立主张的完全接纳,越来越显而易见的是,它已经能够引发一次再次植根于建筑历史辩论、形式困境和将思想转化到空间可能性的对话,而不是以其他方式阻碍话语的权力集中化。值得注意的是,虽然科布的形象与博雅斯基有很大的不同,但论及引发争论的能力,他们有同样的直觉。 事实上,作为剧院作品的空间,GSD托盘的空间秩序将视作其人生的试航。

库伯联盟欧文建筑分院

与此同时在库伯联盟,由弗雷德里克·彼得松设计的预科楼成了约翰·海杜克登上院长宝座的平台。作为该校校友,海杜克对该计划并不陌生,并在1965年调入学校后,率先成为该计划的负责人,直属埃斯蒙德·肖院长领导,而当时美术和建筑学院仍然联合在一起。预科楼的改造工程于1971年破土动工,同一年,题为“建筑师教育——观点”的展览在现代艺术博物馆开幕。这两个事件之间的时间一致性很重要,因为海杜克正在设计预科楼的新格局,同时也在专注于建筑学课程的教学思想。该工程花了3年时间才完成,在此期间,美术学院和建筑学院分离,为1975年海杜克成为建筑学院独立之后的首任院长奠定了基础。

1971年,预科楼改造工程的最初目标是生命安全,最终转变成了海杜克表现——更确切地说,是宣告其教学计划的象征。图书馆设在教学楼的底层,作为知识基础;但不知何故,学校的精神植根于工艺文化,要求学生精通木工、铸造、焊接等工艺。因此,位于四层的车间既是该大楼的地理中心,也是其精神核心,夹在三层建筑学院和五层艺术学院之间。换言之,该大楼的剖面图被看作是海杜克在“制造”理念下畅想艺术与建筑以何种方式融合的直接印记。6)

当然,从彼得松那里继承了这座教学楼,海杜克的使命无论是在结构上还是从地标保护委员会的角度来看都极具挑战性。他完全在内部操作,但也找到了为教学楼的建筑传承作出贡献的方法作为教学策略。该教学楼处于技术转型的临界点,东侧建成了一系列短跨距结构,以界墙分割,而西侧则建成了开放式长跨度结构,作为工作室、车间和开放空间。众所周知,该教学楼具有滚动的结构梁,这在当时属于创造性技术。在教学楼改造工程中,海杜克有效地延伸了教学楼的结构性,通过微缩九宫格(他自己的教学方法的即兴运用,名为九宫格问题)将他所热衷的柯布西耶自由规划加以转换,将其融入预科楼南面的大厅规划。结果是不可思议的,因为虽然在一个层面完全规范,但规模缩小使结构理念陌生化,本质上不再作为支撑,而是创造空间韵律,通过这些空间韵律举办学院的核心社交活动。事实上,九宫格径直落在了评图空间,而这些区域当时是、现在仍是学院举行集体典礼的主要场所;但是它的规模缩小也有助于其他活动的实现,就好像把这些柱子化为空间人物参加活动一般。不用说,作为院长,我现在把自己的个人理解带到了库伯联盟的空间。为避免历史偏差,我尝试解释它的历史,我身处某些事件曾经发生的空间,思考这两者之间的联系。不过,关于海杜克就任之前和安东尼·维德勒就任之后该学院的精神,最有趣的也许是:这座建筑体现了一种特殊的性格和文化,也规避了融入其中的教学方法。

建筑作为舞台布景7)

在这种意义上,通过类比,建筑可以看作是服装:虽然我们的身体受它的限制,但并不完全由它定义。包裹身体与给身体以适当程度的自由之间的矛盾造就了我们身穿该服装时的举止习惯,尤以衣服太紧或太松时最为明显。推而广之,服装成了布景的一部分,我们表现出的形象是我们想象自己穿戴好服装的样子。建筑也可以看作是发生在其中的某些事件、功能和程序的舞台布景;传统戏剧按反复排练的脚本演出,而更多试验剧场,如意大利即兴戏剧,则根据对梗概的理解进行即兴表演,就像我们在日常生活中一样,在自己居住的建筑环境内、在我们经历的事件中扮演各自的角色。想象一下正统宴会上的礼仪与狂欢派对的鲜明对比;我们如何扮演那些角色,在很大程度上,也是由作为其背景的建筑确定的。因此,可以认为建筑是活动的舞台布景,而这些活动是其中上演的事件的扩展、体现、甚至是催化剂。

5 库伯联盟学院外景/History photo of the Cooper Union(4.5图片版权/Courtesy: 库伯联盟学院欧文建筑分院档案馆/The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture Archive of the Cooper Union)

当然,这些学校只是学习空间如何与所处时代的理念平台既融合又背离的3个例子。我们可以就同一问题对所有学校进行研究,也可以评估这些空间对其受众的影响程度及其产生的文化譬喻。有一所学校在其短暂的使用寿命中经历了很多变迁,这就是南加州建筑学院。它最初坐落于圣莫尼卡连体建筑之中,然后搬到了威尼斯海滩的大工棚内,再后来又栖身于货站大楼中,直至今日。虽然这所学校经历了从卡佩到罗通迪、从德纳里到莫斯和迪亚兹·阿隆索的历史及思想巨变,但其“无墙大学”的理念丝毫未变,仍是至今依然遵循的公共遗产的一部分。同时,货站与伯克利大街1800号的圣莫尼卡校园是截然不同的。没有了建筑形式的压力,货站只需要一个和帝国大厦一样长度的开放式走廊;其规模和尺寸的分隔,决定了今天的教学模式:近380m长的评图走廊、在教学楼长度内畅通无阻的连续通勤系统、以及延续了无障碍环境的理念。如此异想天开的尺度和比例有可能在建筑类型、内部功能、类型与功能的对应程度和建筑最终无法满足其形式、空间和组织的使用需求之间引发争论。不论好坏,南加州建筑学院有助于说明一个道理:无论是最积极的建筑师还是最实用主义的客户,都不能保证建筑形式与公众认可度之间的一致性。尽管如此,作为容器,建筑物容纳着我们,就像我们被建筑物包裹着一般,但同时我们也可以自由地解释、利用甚至改建建筑物,并赋予它们新的功能,成为它们文化意义增值的一部分。南加州建筑学院正是如此:一座融合了新文化且极其狭长的建筑物,所有的时光都是从经年岁月的积淀而来,延伸成为那些曾在伯克利大街1800号上演的行为的譬喻。

Beyond this, and behind this, it was Alvin Boyarsky's leadership that gave the AA the presence for which it is still known today, even though it has had three other leaders since –all with their own merit. Faced with the impending danger of closure, Boyarsky realized that he required a completely different financial model and pedagogical strategy to address the diminutive nature of its physical infrastructure. Key to its transformation, as a result, was the introduction of a larger international student population to cushion the need for full tuitions, and in tandem, the transformation of the Unit system into a Darwinian studio whereby the survival of faculty, in part, was based on the popularity of student sponsorship. While Boyarsky held a firm hand on the decisions of the school, he also used the Unit based system strategically to advance the voices of the incoming generation of young architects.

What Boyarsky also brought to the school was a consciousness that in order for a voice to exist, it would need to be heard, and the only way to do that from a row house, was to amplify its message through media and events that could gain permanence beyond his epoch and a distance beyond the country's borders. The churning lecture hall and the revolving exhibition space were given a different presence through the added efforts of the AA publications, which in that time exceeded the authority of a place of instruction; it served to instruct other faculties, not just students. Boyarsky himself not having an architectural practice as such, also understood that he did not need his own designs through which to speak, for his own practice was a curatorial one. In the choices, juxtapositions and overlays he made, emerged a debate, friction and discourse that created the practices for which he is known: where would Koolhaas, Tschumi and Hadid have gone were it not for their moment of trust and empowerment under Boyarsky? Alas, Boyarsky died in 1990, and so too with it, an era that negotiated the challenges of leadership in the context of an architectural setting that was quite particular as a historic building; its adaptive re-use, as it were, was informed by the loosest of fits, and yet the character of the school persists even today to some degree, even with the expansion of row houses, the introduction of dedicated studio spaces and the transformation of the intellectual project in the era of digitization.

The Harvard Graduate School of Design

Designed by John Andrews, Gund Hall at the Harvard Graduate School of Design was completed in 1971, the same year that Boyarksy stepped in as the director of the AA. Although the idea of a new building was the pet project of Josep Lluís Sert, he would never get to preside over it because he had stepped down from the Deanship by 1969. The move from Robinson Hall to Gund Hall was arguably the result of years of work Sert had dedicated in giving birth to the discipline of 'urban design', which at that time, was in its beginnings. Indeed, the idea of the new project was to develop an open and flexible building where Architecture, Urban Design, Landscape Architecture and Planning could share a space under one roof after a period of years of autonomy in different buildings. As such, Gund Hall could be said to be the manifestation of Sert's pedagogical vision, and one of the first to demonstrate a space for inter-disciplinarity.4)

The pyramidal organization of the building is unmistakable in its morphological clarity; its stepped configuration is linked to a range of historical antecedents, and yet completely unprecedented as a space for work and collaboration. Located on a single monumental hall capped by deep trusses, the "trays", as they are called, serve as studio platforms that are punctuated by a series of staircases that break up the vast terraces into sectors, and produce a redundancy of circulation that cannot merely be attributed to fire safety. Indeed, these stairs become the agent of social interaction – or avoidance as it turns out to be on occasion – as they offer a multitude of promenades up and down the building. The terracing of the building is launched by a mezzanine at the bottom that was originally conceived as a lounge, and with each level the students ascend annually, with the thesis year crowning the upper most level. If the aesthetic of the building recalls factory spaces of industrial production, the terracing produces an effect that transforms a benign idea about production into the space of theater; that is, the terraces literally serve as theater seating looking from one level to another, creating within the collective spirit of the civic space, a sense of individual 'presence' as both subject and object of voyeurism. If this interpretation seems overly panoptic, it is also obviously internalized in a myriad of ways by both professors and students alike. While certain students prefer a more contained and protected set of spaces 'under' the terraces, others opt for the open theater of exposure. However, what dominates the space is the sense that the design process is a public activity, that architectural discourse is a collective project, and that somehow, whether as students or faculty, everyone is subject to critical engagement; in effect, by analogy it becomes one large critic space, as the agendas and predispositions of each school of thought becomes exposed to the next. It is maybe poignant to remind us that the AA of the same period had no dedicated studios, and thus most students developed personal alliances with "unit mates" to lease out studio spaces around London, creating more of a balkanized culture, where the various units served as cliques for thinking, drawing, dressing and behavior alike –things that subsequently would be exposed in the space of the bar. Conversely, the large scale of Gund Hall exposed everything in one instance, and here as much as disciplines and individual personas had the opportunity to merge and learn from each other, they also gained the proximity and immediacy of friction, where differences played themselves out in a more public stage of the studio space. It allowed for many schools of thought under one umbrella.

From an administrative and intellectual perspective, the GSD succumbed to a radical detour from 1969 to 1980. With the controversial appointment of Maurice Kilbridge, a Mathematics professor from Harvard's Business School with a doctorate in Mathematics, as its new Dean, the new building gained a steward whose insight into the debates of design were limited; Kilbridge was an economist whose expertise was in applying analytical techniques to urban issues, and thus less invested in the formal, spatial and material research that is part and parcel of architectural education. While Kilbridge did oversee the program's financial woes back to a healthy fiscal balance, his lack of intellectual leadership and connection to his core audience lost him his support and trust from both students and faculty. The temporal aspects of this turn of historical events are ironic, as the launching of a polemical building could not be matched with a leader who could absorb its spatial organization as part of a larger pedagogical plan; instead, the very students and faculty appropriated its very order for the theater of dissent, resulting in the dean's ultimate demise.5)

NADAAA三和弦

正是在这种背景下,我们开始在佐治亚理工学院、墨尔本设计学院和多伦多的丹尼尔斯学院设计辛曼大厦。这3所学院在其历史使命方面的迥异程度可以说无以复加,因此,这种项目类型中,专业知识转化成为最佳建筑形式的可能性都受到限制。出于这个原因,这3个项目恰巧都有一个共同的规划,只是各自的办学理念大不相同。我们最重要的任务是对每个项目进行分析,我们应该更好地理解每个受众的文化和潜力。2008年经济危机对这3个项目造成的损失是致命的。换句话说,辩证地看待问题是它们共有的精神气质,是评估必不可少的因素,建筑师要确保建筑理念的方方面面都以某种方式通过公众及使用者的力量表达出来。

佐治亚理工学院辛曼楼

辛曼楼坐落在佐治亚理工学院校园的中心,与主图书馆毗邻。在委托项目时,曾打算把建筑学院扩建成四号楼,用于教授硕士和博士课程。与此同时,因为大学内开车人的数量众多,于是优先考虑车辆,校园的整个中心区域被停车场占用。随着辛曼楼的适应性再利用,出现了将该区域改造成四分式校园的倡议:更好的沟通创造一个为行人、自行车、休闲和有助于院校之间沟通的公共空间。

辛曼楼由保罗·赫弗南始建于1930年,用于工程研究,正面标有大写的“RESEARCH(研究)”标志。用作试验和研究空间的高架空间是它最显著的特点。在项目委托的早期阶段,空间规划的压力让管理层把高架设置为三层工作室空间,但是在经济危机之后,建筑师对规划进行了修改以便更有针对性地服务学生,并让高架回归其最佳、也是最灵活的用途——用于研究生课程。为此,该项目把封闭了几十年的高架空间向主入口开放,使公众可以进入,并自由参观。第二,作为一个开放式大厅,它的室内公共场所是很知名的,其极具灵活性的优势成为各种不同活动的平台。同样重要的是,该空间也可以作为连接住校区后方进行大型露天“活动坪”的界限。因此需要这种保持地面层开放性的方法,使地面层不受结构、静态功能和固定设施的支配。为此,我们以浅显的方式来讲解该建筑在重塑和再利用方面的建筑特征:实际上,我们把屋顶重新作为基础设施,并把所有新的功能设施从屋顶悬挂下来,使它们不接触地面。我们用卷帘门来悬挂一个工作室,通过一个参数化结构连接二层和三层。我们在南翼悬挂了一个现代的螺旋楼梯,调整了该建筑中出入不便的部分。我们悬挂了一系列隔断墙,将高架空间与侧面的走廊、评图空间和创新实验室等服务空间相连。最后,我们把照明装置悬挂在可调节杠杆上,以便在需要进行高空大型活动时将其调高。由于不接触地面,这些设施可以在不同操控下转动,空间可以转化为各种功能。

有趣的是,硕士课程正在学科评估中发展壮大。然而,令人沮丧的是,当时德高望重的院长托马斯·加洛韦于2007年去世,将该项目的行政领导权交到了道格·阿伦教授手中,后者将全部精力倾注于学院规划之中,在设计过程进行到一半时逝世。继任院长是艾伦·鲍尔弗,广受支持,该项目的建筑事务所凭借该建筑的特点获得了推动硕士课程发展的可能;这是通过设计本身定义其使命和文化的机会。因此,以高架为中心的研究空间成为博士和硕士小组的基地,他们在参数化、建筑技术和可持续发展方面的工作可以以更加科学的方式与设计师进行互动。悬挂结构、水平通透性和空间的可访问性在研究和设计之间营造了一种无缝连接(字面意义上的)。当空间的纯粹及其能够以多种方式被解读的可能性成为定义学院的教学方法、事件、关系和文化的催化剂,是辛曼高架空间使其中一些独特的时刻成为可能。自从几年前开放以来,它已经有机会成为工作室、研讨会、电影放映、演出活动、学术舞会、大型装置甚至是毕业庆典的主要空间,其中许多使用方式是无法预料或进行严谨计划的。

鉴于该项目在很大程度上属于适应性重新利用,我们的大部分工作是将功能特征进行归类,以尊重该建筑的历史属性。这需要高度严谨和敏锐的历史保护政策作为支撑。该建筑系统由混凝土、砖、钢和木材混合而成的,是独一无二的、其当初所处时代的试验性典范;因此,我们的改造减少了材料颜色,战略性地沿用现有材料,以承担新的功能、适应性和用途。现有建筑的构造与新的干预措施相结合,如果从众多领域上的实践来看,每一种理念都会对保护、改造和干预——探索本项目所需要的透镜——的性质产生重大影响。在阐述和曝光各种构造细节的过程中,本项目已经成为一种样例(历史和现代的),试图呈现各个领域的各项重要探索,而后续各种语汇的调和则是未来学科教学项目的一部分。

墨尔本大学设计学院

6 佐治亚理工学院辛曼楼/Hinman Building, Georgia Tech(摄影/Photo: Jonathan Hillyer)

基于国际竞争趋势,墨尔本设计学院应运而生,其建院宗旨在于创建“未来设计工作室”,以打破零专业工作室的局面,创建跨学科研究,以满足“新的学术环境”需求,创建“有生命的建筑”,以将可持续理念融入环境管理,并创建“教学楼”实现创新型学习模式并发挥教学启蒙作用。设计学院院长汤姆·凯文准确定义了该建筑的使命,并付诸努力开设各种课程——互相学习,互帮互助,融合工作室及研究文化。该建筑位于墨尔本大学主广场“康克瑞特草坪”旁,为该校主教学楼。因此,除设计课程外,该建筑还用于其他学院学科研究,包括开展研究活动,学术活动、展览和实验项目,与其他研究领域共享教学设施。

In 1980, with the hiring of Gerald McCue as Dean and Harry Cobb as Head of Architecture, the building would finally gain a leadership that was deserving of its theatrical motivations. Harry Cobb's launching speech, "Where I Stand" outlined a series of principles around which he would want the school to revolve: architecture's commitment to the city, the coherence of a structural order to the program, the critical evaluation of rigor, a new openness that could draw in the necessary ideological friction to motivate varied forms of practices, and finally the presence of audacity: to risk, to fail, to challenge. As a practicing architect, then in his mid-fifties, Cobb had already established himself as a reputable designer within a very successful partnership; buildings such as the Hancock Tower and One Dallas Centre both built just years before his appointment, found ways in which to transform the mandates of corporate commissions towards more architecturally speculative ends, pushing building technologies to new ends, radicalizing the perceptual effects of commonplace materials and teasing out invention out of the normative, even the banal. Still, by any measure of the academy, he would be seen as a safe and sound voice, not necessarily the one to take risks. For this reason, his ability to deliver the very tenets of his opening speech would be taken as a testament to his own audacity to transform the school to a hotbed of debates, almost instantly. Not aiming to replicate the model of his practice within the academy, Cobb's curatorial selections for newly invited faculty produced explosive reverberations around the school. With some embracing the new voices and others in complete resistance, what became clear was that he had been able to convene a conversation that was once again rooted in the debates of architectural history, the predicaments of form, and the speculative possibilities of translating ideas into spaces, rather than the centralization of power that might otherwise suffocate discourse. Notably, while Cobb's profile varied significantly from Boyarksy, when it came to the ability to convene a debate, they shared the same intuitions. Indeed, the spatial order of the GSD trays would be taken for the test ride of their life, as a space of theatrical productions.

The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture of the Cooper Union

Meanwhile at the Cooper Union, the Foundation Building designed by Fredrick A. Peterson, served as the platform for John Q. Hejduk as its Dean. As an alumnus of the school, Hejduk was no stranger to the program, and after joining the school in 1965, he first became its Head under Dean Esmond Shaw, while the School of Art and Architecture were still conjoined. The renovation of the Foundation building broke ground in 1971, the same year of the exhibition titled "Education of an Architect: A Point of View" was opened at the Museum of Modern Art. The temporal alignment between these two events is important, because as Hejduk is designing the new layout of the Foundation Building, he is concurrently focused on the pedagogical thinking behind its program in Architecture. The construction took three years to complete, and in that interim period, the School of Art and Architecture broke off into their own divisions, establishing the position for Hejduk to become the first Dean of the School of Architecture as an independent entity in 1975.

Originally conceived as a project for life-safety purposes in 1971, the renovation of the Foundation Building transformed to become Hejduk's manifestation – indeed a manifesto – of his pedagogical plan. The Library was set at the building's base, as a foundation of knowledge; yet somehow, the ethos of the school was rooted in the culture of craft, and the pedagogy required students to familiarize themselves with the tools of wood-working, casting, welding, among other things. For this reason, the workshop served as both the geographic and spiritual core of the building, on the fourth floor, sandwiched between the School of Architecture on the third floor and the School of Art on the fifth. In other words, the sectional diagram of the building was seen as a direct imprint of the ways in which Hejduk imagined the confluence of Art and Architecture in the context of "making".6)

Of course, having inherited the building from Peterson, Hejduk's mission was a challenging one, both structurally and from the perspective of Landmarks Preservation Commission. He operated on the interior exclusively, but also found ways in which to contribute to the structural legacy of the building, as a didactic strategy. The original building was constructed at a critical threshold in technological transformations, and thus, the east side is built in a series of short spans with party walls while the west side is built as a longspan structure with an open plan, which was to serve for studios, workshops and open spaces; the building is known for having rolled structural beams, which for its time, was an inventive piece of technology. In renovating the building, Hejduk effectively extends the structural narrative of the building by translating his obsession with the Corbusian free plan by miniaturizing a nine-column grid –a riff on his own pedagogical exercise called the nine-square grid problem– to fit into the plan of the lobby on the south portion of the Foundation Building. The result is uncanny, because while completely normative at one level, its reduced scale de-familiarizes the idea of structure altogether, no longer there to serve as support per se, but to create spatial cadence through which the core social activities of the schools could occur. Indeed, the nine-square grid falls directly in the critique spaces that were, and remain, the main collective ritual of the schools; but its diminutive scale also helps to entangle the very activities it seeks to enable, as if to make the columns into figures in the spaces, participants in the activities. Needless to say, as Dean, I now bring a personal reading to the spaces of Cooper Union that escapes historical distance. I interpret its history and I inhabit the spaces within which certain events occurred, thinking about the relationship between the two. Still, maybe what is most interesting about the ethos of the school predates Hejduk and survives Anthony Vidler: the building embodies a certain character and culture that also escape the very pedagogies that are cast within it.

Architecture as Mise en Scène7)

In this sense, by analogy, architecture can be seen as clothing: while it constrains our body, our bodies are not exclusively defined by it. That tension between capturing the body and yet giving it just the right level of freedom produces the behaviors we practice in the very clothing we wear, most apparent to us when they are too tight or too loose. By extension, clothing becomes part of a mise en scène, as we play out the characters we imagine ourselves to be within the costumes we inhabit. Architecture, too, can be seen as a mise en scène for the very events, functions and programs that occur within it; and while traditional plays are scripted with over-determination, other more experimental theaters, such as the Commedia dell'arte, adopted improvisation as the basis for the interpretation of a sketch, much as we do in life as we play out our various roles in the context of the buildings we inhabit and the events we undergo. Consider the decorum that is expected in a black-tie party in contrast to a rave; how we play out those roles, in great part, is also defined by the architecture that is its backdrop. Thus, one can think of architecture as the mise en scène for the activities that are an extension, reflection, or even a catalyst for the events that play out within them.

Naturally, these schools are but three examples of how the spaces of learning have been simultaneously aligned with and in a state of disjunction with the conceptual platforms of their time. We could inspect all schools in terms of the same question, and we could evaluate the degree of impact these spaces have had on their audiences and what cultural tropes they produce. One school that has been through a lot of change in its short lifespan is Sci-Arc, first located in the medley of conjoined buildings in Santa Monica, then in a large industrial shed in Venice Beach, and subsequently in the long Freight Depot Building it inhabits today. While the school has undergone significant historical and intellectual transformations from Kappe to Rotondi, and from Denari to Moss and Diaz Alonso, the concept of the "college without walls" remains intact, and part of a shared legacy that is still practiced today. At the same time, nothing can be more different from the Santa Monica campus on 1800 Berkeley Street in comparison to the Freight Depot. Without the burden of exhaustive narrative, the Freight Depot simply requires an open promenade the length of the Empire State Building; the sheer extremity of its proportions, and dimensions, radicalizes how the institution operates today, with a crit wall that is virtually 380 meters long, a commuter system of skateboards that expedite the trek over the length of the building, all while maintaining the idea of a barrier free environment. It is not uncommon that such a conceit of dimension and proportion might prompt a discussion between building typology, the functions that inhabit it, their degree of correspondence and the ultimate inability for architecture to make a claim of inevitability to its forms, spaces and organizations. Sci-Arc, for better or worse, helps articulate that neither the most optimistic of architects nor the most positivist of clients can ensure the alignment between architectural form and human reception. Still, as vessels, buildings contain us, and as much as we are entrapped by them, we are also free to interpret them, use them, abuse them and give them new functionalities that become part of their accrued cultural significance. Sci-Arc is just that: a curiously long building that forces certain new cultures within it, while all the time extending certain inherited behavioral tropes from years long gone at 1800 Berkeley Street.

然而,前期分析研究及价格预算暴露了一个悲惨现实:新建筑功能之一是创建专业工作室,但所拨付的经费无法满足这一需求。同样,在该建筑主体工程基础上,基于总预算设置工作室,拓宽拟建的中庭走廊,摆放家具并在墙壁布置装饰品,摆放模型制作桌、小组桌、绘图桌,并建造会议室。家具由FF&E(家具、固定资产及设备)来承担抛光的工作。因此,中庭建筑未设计栏杆,而是增加建筑悬臂部分,并使用不锈钢网将家具“拆封”成块,打造天然但多孔的安全屏障。中庭内为工作室空间,灵活设置办公桌学习点,每个点位可随时满足50%的学生在此学习工作。

在设计过程中我们发现,从类型学角度看,新的建筑与原址建筑实际功能相同。然而,基于此,我们对原有建筑的缺陷进行系统分析,解决相应缺陷并采纳其优点。原有建筑与周边环境隔绝,而拟建建筑通过其孔洞并延伸至学校之间的散步长廊与周边环境紧密连接。原有建筑中庭由坚固的墙壁包围,几乎没有出入口;所拟建筑中庭则采取多孔建筑模式。原有建筑走廊空间宽敞,但相对封闭,与教室或中庭均无连接;拟建建筑战略性采用可移动墙壁及壁炉,以创建灵活交流空间。原有建筑一楼公共空间隐秘,而拟建建筑则开放图书馆、礼堂、加工实验室和展览室,同时将中庭楼层提升至“主要层”,创建更为开放的空间。新建建筑体现一系列变化,而在各方案中,我们找到了解决原有建筑缺陷的方案,将其文化、记忆及仪式感融入新的设施,弥补原有建筑的不足。因此,这一过程形成了一种自我意识,我们甚至思考是否可以将原有建筑建成我们所翻新的结构,但遗憾的是,建筑过旧,结构不稳定且翻新造价过于昂贵。

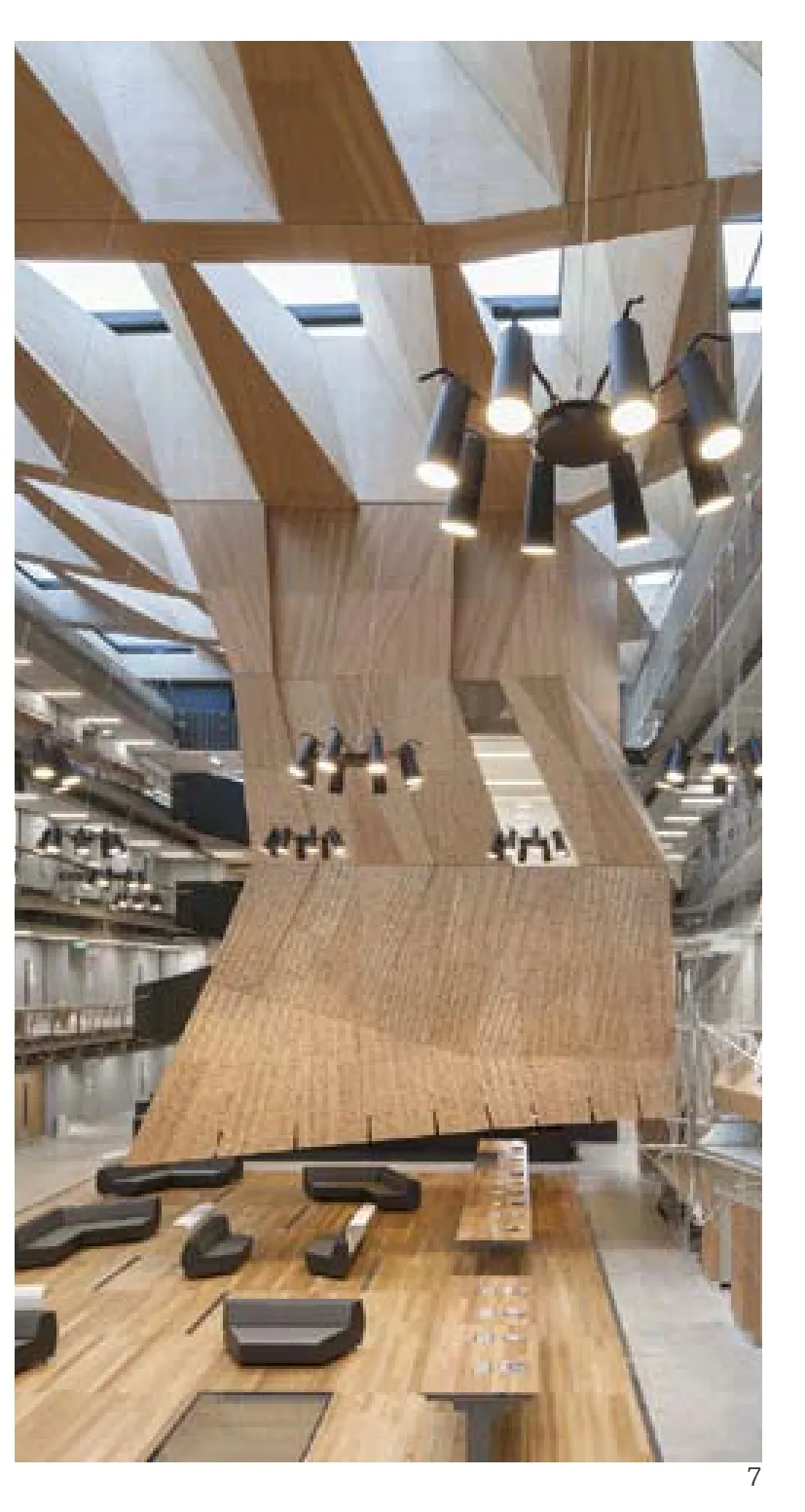

MSD项目也开发了一系列建筑模块——构造、方案、空间及细部——构成“教学楼”。本文中,我们将佐治亚理工学院融入新的环境,但基于不同目的中庭部分,我们开创了结构体系,创建双向档板,跨度约22m。通过LVL(単板层积材)焊接,挡板弯曲可阻挡太阳光直射入内部空间,并确保工作时间光照充足。更重要的是,屋顶的深度可确保工作室结构沿挡板延伸。作为教学设施,为了将“分层级”的构造模式转变成为随主体下降的结构体系,屋顶结构及悬浮工作室之间的构造差异是很大的挑战。因此,采用尺度和容量巨大的顶部来满足需求。木结构逐渐压缩形成肌理,且随进一步下降在其上悬挂薄的胶合板贴面。悬挂结构底端安装了薄格栅板,形成了开放的声学环境,并与这种形式内部的技术装置相协调。教学楼中的这种构造体现了帕拉齐叠加层的经典分层顺序,但为了更好的感官体验,将多变的功能置于底层。作为一个重大的悬浮装置,它直接体现了内部负荷的实际变化,此处论证以作启示。

MSD人数众多;该项目是其内在多元文化的景观文化交叉,从建筑到城市化,从规划到环境学,等等。是什么让凯文院长的4个理念得以行之有致的精心体现出来是这个新构造的发明——悬浮工作室——通过将良好的愿景进行适宜的层级化分带来了一个喘息的机会。悬浮工作室是一个奇迹,令人敬畏,但却并没就其初衷作出解答:教学方式应该被具体化或量化在哪个阶段呢?当这种尝试不足以解释空间形体和现象行为在逻辑层次上的倒置时又会怎么样呢?

多伦多大学丹尼尔斯建筑景观设计学院

多伦多大学的丹尼尔斯楼位于士巴丹拿新月街中心,这是一个独特的、具有灵活且知名城市网格的公共空间。随着1875年老诺克斯学院的建立,坐落于南部边缘,过去几十年间,该区域进行了多次规划:神学院、军队医院、博物馆及用于研究胰岛素的实验室。因此,该建筑顺应了历史及时代潮流的变迁。其六边形空间被用作教室、办公室、会议室空间,并满足了声学及视觉相互分离的需求。同时,采用了开放的空间规划以确保该学院具备更多工作室及设计实验室。北部的扩建卓有成效:沿士巴丹拿新月街北部设置立面,提供更多灵活空间,将士巴丹拿新月街城市化,并使其东西部便捷地通往学校及哈伯德村。

学院下设建筑、景观建筑及城市设计3个专业,本文将基于这三点解读设计,拉近士巴丹拿新月街与多伦多市的距离。参考NADAAA的其他设计项目,设计过程中详细分析了前述3个领域的融合,并将其研究融入建筑构造之中。基于研究内容,GRIT实验室(绿色屋顶创新测试实验室),“装配实验室”及“全球城市研究所”在赋予建筑更多教学空间方面发挥了重要作用;更为重要的是,各元素有助于拉近城市和景观的距离,有助于形成建筑扩建的战略举措。因此,可将该建筑视为建筑体系的普适理念及景观理念得转变两者之间完美融合。

该建筑的概念图则可诠释为一个简易的盒子,以最紧凑的空间将诺克斯学院的流线进行延伸。在这个盒子中,各层楼板弯曲产生形变以连接不同的学科是通用的处理方式。从街道层面看,广场东部开放成为走廊,从而拟建全球城市研究所,西部则建立哈伯德村;这两个学科由步行街连接,构成公共交通体系,由该建筑通往罗素大街。建筑北部则将装配实验室延伸至外部庭院,使搭建大型模型成为可能;北部则通过调整景观尺度,加强与士巴丹拿北街的对称性,从而使东西部相互连通。第二三层楼板则由垂直步行走廊连接,将顶层工作室与内部道路相连接;这是建筑中最为重要的部分,它将二层的本科生部与走廊相连接,同时将自然光照充足的三层与走廊进行无缝连接。因此,建筑顶层的景观将结构、日照及水循环系统在外立面进行调合,这也是该建筑最重要的空间实体及其标志性的特色,这一构造将各学科相互融合,构成了其统一的整体——教学空间。

结论

7 墨尔本大学设计学院/Melbourne School of Design,Melbourne University(摄影/Photo: John Horner)

本文讨论的核心内容,基于两种建筑学观点的不可调和性,通过教学方法理念的完善来实现。一方面,这是罗兰·巴奇环境调度理念,其中建筑设施在行为、叙述及方案构造中发挥更具指导性且确定的作用。另一方面,相反观点认为建筑设施提供的只是一种气氛,如同电影中的配乐,旨在表达隐密且令人难以觉察的理念,同时也将整个情节融入其所设定的剧情。对于后者而言,音乐的出现依旧是一种工具,且其将建筑融入背景的隐形作用是反应人物精神状态的要素。然而,如果取消惊悚小说中的音乐,这种状态并不能停止,某些不可复归的元素、紧张情绪及焦虑并没有消失。由此而言,多种形式表明建筑并非完全属于白噪声,而是一种催化剂:GSD的衍架构成了不为人知的“衍架比赛”的雏形, RISD休息室为各类临时交谈提供场所,AA学院吧台为各种辩论提供场地。除了上述建筑学院中传达出的教学理念,还有非主流文化作为砂浆,填补着建筑的孔洞,这就是建筑促进各类文化相融合的方式。□

The NADAAA Triad

It is against this backdrop that we set out to design the Hinman Building at Georgia Tech in Atlanta, the Melbourne School of Design in Melbourne and the Daniels Faculty in Toronto. The three schools cannot be more different in terms of their mission, and as such, any alleged expertise in this program type would be limited in its ability to deliver optimal results. For this reason, the projects happen to share a common program, but vastly different from their respective institutional perspectives. Our analytical task for each project was possibly the most important, if not to better understand the culture and potential of each audience, then to compensate for the fact that the economic crisis of 2008 dealt a near fatal blow to all three projects. In other words, the ethos that they all share is a sense of critical choices, to evaluate the indispensable and to ensure that all aspects of architectural ideas were somehow couched in relation to the forces of integrated alibis.

The Hinman Building, Georgia Tech

The Hinman Building is situated in the center of the Georgia Tech campus, next to the main library. At the time of the commission, it was to expand the School of Architecture into a fourth building, slated for the Masters and PHD programs. Concurrently, the entire center of campus was occupied by a parking lot, effectively giving primacy to vehicles as the driving identity for the university. In tandem with the adaptive reuse of the Hinman Building, there was an initiative to transform the space into a campus quad: a public space for pedestrians, bikes, leisure and better communication between schools.

The Hinman Building was originally built in the 1930's by Paul M. Heffernan for engineering research, marked boldly with the sign, "RESEARCH" on its front. Its most salient quality was a high-bay space that served as the space of experimentation and exploration. In the early parts of the commission, the pressures of space planning had the administration packing the highbay with three stories of studio space, but after a sober recognition of the economic crisis, the program was revised to reduce student numbers, and in turn put the high-bay to its optimal –and most flexible—use for graduate studies. To this end, the project opens up the high-bay space to the main entry, something that had been blocked for several decades, making it publicly accessible and open to view. Second, as a large open hall, it was celebrated as a potential public interior, taking advantage of its flexibility to serve as a platform for varied functions. Equally importantly, the space could serve as a threshold to connect the main quad to a back "working court", where large scale experiments could be fabricated outdoors. This required an approach that maintains the openness of the ground level, leaving it unencumbered by structures, static programs, and immobile elements. For this reason, we interpreted the building's characteristics in unorthodox ways, but in ways that could enable its reinvention, and repurposing: in effect, we re-interpreted the roof as foundation, and suspended all new interventions from the roof down, so they would not touch the ground. We re-purposed the gantry crane to suspend a studio space to link the second and third level of the building by way of a programmed structure. We suspended a new spiral stair on the south wing, to activate what had been the least accessible part of the building. We suspended a series of "guillotine" walls, to connect the high-bay space with service spaces on the side: galleries, crit spaces and fablabs. And finally, we suspended the lighting on adjustable rods such that they could be elevated for large scale experiments that require high sections. By not touching the ground, the furnishings can be rolled around in varied configurations and the space can be transformed into a variety of functions.

At the time the Master's program was in the process of expanding and re-evaluating its discipline streams. However, tragically, the much-admired Dean of the time, Thomas Galloway passed away in 2007, putting the administrative leadership of this project in the hands of Doug Allen, a senior professor whose wisdom was central to the programming of the school, who also passed away during the middle of the design process. With a very supportive Alan Balfour as the incoming Dean, the project's architectural agency gained the power to drive the potentials of their Master's program through the very attributes of the building; this was an opportunity to define its mission and culture through design itself. As such, the research spaces around the high-bay served as home bases for PHD and Masters groups, whose work in computation, building technologies and sustainability could interact with designers in a more unmediated way. The suspended structures, the horizontal transparency and accessibility of the space, created a seamless connection (literally) between research and design. The Hinman high-bay space is one of those unique moments when the sheer power of a space, and its potential to be interpreted in diverse ways, becomes a catalyst for defining pedagogies, events, relationships and the culture of the school. Since its launching some years ago, it has had the opportunity to become a space for studios, seminars, movie projections, pop-up events, the Beaux Arts Ball, large scale installations, and even graduation – many of which could not have been anticipated or planned in a strict sense.

Given that the project, in great part, was an adaptive re-use, much of our work went into the assignment of characteristic features to respect the historic attributes of the building. Much of this required careful and discerning historic preservation tactics. The building's systems, composed of a hybrid of concrete, brick, steel and wood was unique, and exemplary as an experiment of its time; as such, for our interventions, we reduced our palette of materials, strategically grafting the existing materials to take on new functions, adaptability and purpose. The tectonics of the existing building, in combination with the new interventions, if seen individually as exercises on their respective media, each take on a discursive role about the nature of preservation, renovation and intervention –the three lenses through which we needed to explore the project. In the articulation and exposure of the details of the various tectonic parts, the project has become an archive of sorts (both historic and contemporary) that attempts to present the individual material explorations on their own terms, while their subsequent syntactic reconciliation is part of the larger pedagogical project of the discipline.

Melbourne School of Design, Melbourne University

The Melbourne School of Design was the result of an international competition whose main goal was to create a 'design studio of the future' for a program that had never had dedicated studio spaces, to create a "new academic environment" rooted in inter-disciplinary work, to create "a living building" whose approach to sustainability serves as a model of environmental stewardship, and to create a "pedagogical building" such that it not only serve as an innovative space of learning, but also function as an exemplary didactic instrument. The Dean, Tom Kvan, had effectively defined the mission of the building and with it, an effort to open up the school to its various programs – to learn from each other, to collaborate, and to mix studio and research cultures. Located next to the "Concrete Lawn", the main plaza of the university, the building stood to serve as the main academic building. For this reason, the base of the building could host not only the design programs, but also reach out to other schools, drawing in their attendance for lectures, scholarship, exhibitions and laboratories, sharing its facilities with other fields of study.

Curiously, early analysis and pricing sets exposed a tragic reality: that while one of the main reasons for the new building was to create dedicated studio spaces, this was the one thing they could not afford within the allotted budget. As such, the organization of the building owes its composition, in great part, to our efforts to smuggle the studio space within the net to gross equation, effectively widening the corridors around the proposed atrium to stack furnishings as infrastructure for open pinup spaces, model-making tables, group tables, drafting desks, and seminar rooms. The budget for the furnishings was drawn from the existing FF&E (furniture, fixtures and equipment) budget, but was translated into fixed millwork scope. Thus, the architecture of the atrium eliminates the need for railings by cantilevering portions of these pieces of furniture, and using a stainless-steel mesh to 'shrinkwrap' the furnishing to the slabs, creating a natural, yet porous, safety barrier. The inner liner of the atrium became the studio space, populated by hot-desks and stations, and created the opportunity of about 50% of the student population to be working at a station at any given time.

The irony of the new building – something we discovered half way through the design – is that from a typological point of view, it was virtually identical to the very building it was meant to replace. However, understanding this, we systemically began to analyze the deficiencies of the old building, to overcome them, while also radicalizing its positive attributes. The former building had an insular relationship to its context; the proposed building urbanized its connections by making it porous on all sides, and by extending the University's main promenade to go through its base. The atrium of the old building was surrounded by solid walls, with little or no access into it; in the proposed building, the atrium would be porous. The corridors of the old building were wide purgatory spaces, neither linked well to the classes, nor to the atrium; in the proposed building, the furniture program would strategically use movable walls and inglenooks to create flexible spaces of interaction. The ground floor of the old building concealed its public programs; the proposed building would expose its library, auditoria, fabrication labs and exhibit spaces, while lifting the atrium floor to the "piano nobile" and creating a more public base. The list of systemic change goes on, but in each scenario, we developed a clear and critical approach to the liabilities of the old building, while extending its culture, memory and practices into a new facility that wore the old building as its ghost. So much so did this process become self-conscious, that we even posed the question whether the old building could become the structure from which we renovate, but alas, it was old, unstable and more expensive to renovate.

8 多伦多大学丹尼尔斯建筑景观设计学院/Daniels Faculty of Architecture Landscape and Design, University of Toronto (图片版权/Courtesy: NADAAA)

The MSD project also develops a series of architectural pieces – features, scenarios, rooms, and details – that rise to the occasion of the "pedagogical building." Here, we translated our lessons from Georgia Tech to a new context, but with new aims. For the atrium, we developed a structural system, whose coffering created a deep two-way slab, spanning over twenty-two meters. Fabricated from LVL (laminated veneer lumber) beams, the distortions of the coffering help to block direct sunlight into the space while ensuring ample daylighting throughout working hours. More importantly, the depth of the roof provides the structure for a suspended series of studios that extend the logic of the coffering down the face of the iconic volume. As a pedagogical device, the innate typological and tectonic differences between the roof structure and the suspended studio is challenged in lieu of a strategy that "graduates" tectonic transformations in the structural system as it descends; as such, it is massive and volumetric at the top, where it requires mass. The wooden members gradually compact to become basreliefs, and as they descend further, suspended thin plywood veneers. The end-grain on the bottom of the suspended structure produces a thin waffled ceiling that provides an open, yet acoustic environment, while coordinating the technical apparatus within its patterning. The tectonic transitions speak to the way in which the classical orders graduate in the stacking floors of palazzi, but here the inversion adopts the wonder of levity as basis for an embodied experience. As the weighty object floats overhead, its surface registers the actual transformation of loads in tension, here made evident as a didactic index.

The MSD population is a large one; the cross section of the MSD project is an index of the various cultures that it houses, from architecture to urbanism, from planning to environmental studies, and beyond. What it does effectively in the careful orchestration of Dean Kvan's four points, it also does in the invention of a new trope – the suspended studio – that offers a respite from the rationalized categorization of intentions. The suspended studio belongs to the category of wonder and awe. It does not so much answer a question as it poses one: to what degree can pedagogy be specified and calculated and how might that be up-ended by a formal spatial and phenomenal act that serves to embody what a lesson cannot.

Daniels Faculty of Architecture Landscape and Design, University of Toronto

The Daniels Building at the University of Toronto is located at the center of Spadina Crescent, one of the unique civic spaces in the city that deviates from the rigidity and anonymity of the city grid. With the Historic Knox College, built in 1875, anchoring its southern edge, the Circle has been host to numerous programs over the decades: a theological school, a military hospital, museum, and subsequently laboratories for the research of insulin. As such, the building has already demonstrated its resilience in face of historic and programmatic changes over time. Its cellular spaces make for ideal classrooms, offices, conference areas and spaces in need of acoustic and visual separation. At the same time, in order for the school to gain spaces for studios and design laboratories, it would need to expand to accommodate for open plans. The expansion to the north achieved a few objectives: giving a north facade for Spadina Crescent, offering much needed flexible spaces, urbanizing Spadina Crescent and making it accessible on the east-west axis to both the University and the Harbord Village neighborhood.

Given the faculty composition in Architecture, Landscape Architecture and Urban Design, this was also an opportunity to engage the three discipline streams to imagine a more engaged relationship between Spadina Crescent and the City of Toronto. As with NADAAA's other design school projects, part of the design process involved a detailed understanding of how the three faculty streams operated, and a way of incorporating their research into the organization of the building. In the context of the research, the GRIT lab (Green Roof Innovation Testing Laboratory), the Fabrication lab, and the Global Cities Institute all played an instrumental role in giving shape to key pedagogical spaces within the building; more importantly, each of them helped to form an important relationship with the city and landscape, helping to inform a strategy for the building at large. To this end, the building can be seen as a delicate negotiation between the most generic of building systems, on the one hand, and the translation of landscape ideas as manifest through a complex section, on the other.

The building's massing, thus, is construed as a simple box, extending the circulation of Knox College around a loop to frame the site in the most compact way possible. Within this box, each floor slab is subsequently deformed to help connect each program with its context in the most strategic manner. On street level, the Gallery opens up onto a plaza on the east side, while the proposed Global Cities Institute reaches out towards the west to create a stoa towards Harbord Village; these two programs are reinforced by a new inner pedestrian street that forms a public conduit that effectively extends Russell Street through the building. On the north side, the lower level extends the fabrication lab into an outdoor court, where large scale mock-ups can be built; the landscape in the north responds to this with volumetric adjustments that reinforce the symmetry of the site on axis with Spadina North, while accommodating the anomalies of the east and west. The second and third floor slabs are conjoined by the new vertical promenade that connects the inner street with the studio space on the top floor; this is the most important landscape within the building, as it visually connects the street with the undergraduate program on the second floor, while physically connecting the same street with the third floor in a seamless fashion, drawing in natural light to the dark core of the building. To cap this off, the roof of the building produces a landscape that merges the structural, daylighting and hydrological mandates of the building into one surface – maybe the building's most important physical, spatial and symbolic feature, since it is this one gesture that brings together the various inter-disciplinary forces to create an integrated strategy: a pedagogical moment.

Epilogue

At the heart of this discussion, there is maybe an irreconcilable relationship between two views on the agency of the formal, spatial, and material qualities of architecture as a catalyst for intellectual – and by extension pedagogical – consciousness. On the one hand, there is a Barthesian idea of mise en scène, whereby the architectural setting plays a more scripted and deterministic role in framing the actions, narratives and scenarios of a school's presence. On the other hand, there is the counterpoint that sees the architectural setting as providing no more than an atmosphere, as if the music score for a movie, which is at once meant to be stealth and inconspicuous, but also completely integrated into the very plot it sets. In the latter, the presence of music is no less instrumental, and yet its recessive role places architecture in the background, the victim of the human state of distraction. And yet, were the music score of the thriller be turned off, we would stop in our tracks, knowing that something irreducible was missing, the tension and anxiety lost. In this sense, architecture is not exactly white noise, but a catalytic agent, and its evidence comes in many forms: the trusses at the GSD that form the basis for the infamous 'truss races', the bunny lounge at RISD that served as the basis for many unplanned encounters, and the AA bar, that served the juice for the many debates for which it continues to be known. Beyond the formal pedagogies that frame the trajectories of these schools, there is the mortar of the informal cultures that are bred into the pores of its architecture –that is how architecture forms the culture of these settings.□

注释/Notes

1)米歇尔·福柯,这不是一个烟斗/Michel Foucault, This is Not a Pipe, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), 19.

2)这跟路易斯·阿尔都塞理论是一致的,即上层建筑不仅仅是经济基础的反映,且文化及其意识形态状态(建筑是其中之一)确实可以对基地产生革命性的影响。/This follows the Althusserian idea that the superstructure is not a mere reflection of the economic base, but that culture and its ideological state apparatuses (architecture being one of them) could indeed have a transformative impact on the base.

3)彼得·库克在《建筑评论》的文章/Peter Cook, The Architectural Review, Alvin Boyarksy (1928-1990), September 28, 2012

4)塞特通常被誉为“城市设计”学科的创始人一书,根据“何塞普·路易·塞特:城市设计的建筑师”一书中关于冈德楼的描述,其他学科的扩建可以被看作是专业化理念在其他平行流的延伸/Sert is commonly credited as the disciplinary founder of "urban design", as attributed in "Josep Lluis Sert: The Architect of Urban Design", edited by Mumford and Sarkis, but in the context of Gund Hall, the expansion of the other disciplines can be seen as an extension of the idea of specialization in other parallel streams.

5)The Harvard Crimson, Anonymous , A New Dean For the GSD, March 17, 1976

6)Hejduk video, Architecture Archive, The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture of the Cooper Union

7)这里笔者借用了罗兰·巴特关于舞台场景的语汇,后来被马卡多·塞尔维蒂称为“建筑场景”,即建筑大环境的每一个属性都是重要的,就像剧本旁白也很重要/Here I borrow the Roland Barthes Semiotic idea of the mise en scène, later re-coined by Machado Silvetti as "mis-en-architecture", whereby every attribute of the architectural setting is seen as significant, as if a protagonist of the play and not just a backdrop.

NADAAA建筑事务所

2017-08-09