Combined Hangzhou criteria with neutrophillymphocyte ratio is superior to other criteria in selecting liver transplantation candidates with HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma

2015-12-24

Chengdu, China

Combined Hangzhou criteria with neutrophillymphocyte ratio is superior to other criteria in selecting liver transplantation candidates with HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma

Guang-Qin Xiao, Jia-Yin Yang and Lu-Nan Yan

Chengdu, China

by preoperative radiographic imaging. Unfortunately, preoperative radiographic imaging can be inaccurate.[6]In addition, microvascular invasion and tumor differentiation, which are considered crucial factors for tumor recurrence, cannot be observed on imaging. Although tumor characteristics such as differentiation can be partly determined by liver biopsy, this procedure is invasive and has the risk of causing tumor metastasis. Therefore, it is necessary to identify tumor markers that are easily obtainable, noninvasive and have predictive value in prognosis.

Most (70%-80%) of patients with HCC are due to underlying chronic inflammation such as hepatitis virus infection or cirrhosis.[7]It is well established that the inflammation contributes to the angiogenesis, proliferation and metastasis of the tumor.[8,9]The neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) as a simple indicator of inflammation in the tumor microenvironment has been proposed to be an independent prognostic factor for patients with HCC.[10]Moreover, an elevated NLR is an independent predictor of tumor recurrence and patient death after hepatectomy.[11-13]This association has also been found in patients with HCC who have received LT.[14-18]

In the patients who fulfilled the Hangzhou criteria, the 5-year survival rate and recurrence rate are 75.6% and 20%, respectively.[19]Gao et al[20]reported a similar overall survival (OS) rate among patients who fulfilled the expanded criteria including the Hangzhou and Shanghai criteria but found a higher recurrent rate compared with studies using the Milan criteria. Therefore, our study aimed to establish a set of new preoperative criteria combining the NLR and Hangzhou criteria to select appropriate patients with HCC for LT in China.

Methods

Patient selection

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of West China Hospital of Sichuan University. Written informed consent was obtained according to theDeclaration of Helsinki. Patients' medical records were obtained from the China Liver Transplant Registry (CLTR) database. Demographic and clinical-pathological data were retrospectively collected from 408 patients with HCC who had undergone LT at our center between February 1999 and September 2012. The images of preoperative CT or MRI obtained within one week before the LT were reviewed to assess the size, number and vascular invasion status of the tumor. Pathological analysis of surgical specimens was made postoperatively to confirm the final diagnosis of HCC and other important tumor characteristics, such as the degree of differentiation.

As part of the routine examination of LT patients, blood test had been performed within 1 week before surgery. We retrieved the absolute neutrophil and lymphocyte counts to calculate the NLR value. Patients with preoperative sepsis, massive gastrointestinal tract bleeding or hypersplenism or those treated with high-dose steroids were excluded from this study. We also excluded the patients without critical data such as the results of blood test, preoperative radiographic imaging or postoperative pathological analyses. Furthermore, we excluded patients who were under 18 years old or were not diagnosed with HBV infection. In addition, patients who died within 1 month after LT were also excluded.

Surgical procedures

A modified technique for adult-to-adult living donor LT was used at our center. The retro-hepatic portion of the inferior vena cava was removed along with the liver, and the piggyback technique (which preserves the recipient's inferior vena cava) was used for the living donor LT patients. In the early years, the standard technique used at our center for deceased donor LT did not involve the veno-venous bypass. The piggyback technique was used for most of the deceased donor LT patients.

Postoperative treatment

After surgery, the patients took immunosuppressive drugs including corticosteroids, cyclosporine or tacrolimus, with or without mycophenolate mofetil. The blood concentrations of cyclosporine, tacrolimus or mycophenolate mofetil were maintained as low as possible as long as the patients had normal liver function. Typically, the corticosteroids were withdrawn after 3 months. HBV immunoglobulins or antiviral drugs such as lamivudine, adefovir, telbivudine or entecavir were administered to HBV-positive LT patients after surgery.[21]

Patient follow-up

The mean follow-up time was 5.4 years (1.1-10.7). After surgery, the patients were followed up at outpatient clinics or by telephone, and the recipients were examined at our center every month in the first 6 months and then every two months for the following half year, every 3-6 months thereafter or when necessary. The examinations included routine blood test, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) test and chest X-ray. Abdominal CT or MRI, chest CT, head PCT and bone scans were also used when necessary. Biopsy was performed for patients with suspicious lesions of the liver or lung. Headache, bone pain or progressive growth of tumor was recorded. The date of tumor recurrence was defined as the time at which the AFP level began to rise and tumor recurrence was confirmed. The date and cause of death were also recorded.Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v17.0 software. The optimal cut-off value of NLR was determined using a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, and the results were used to classify the patients into the two study groups. Univariate analyses including an independent samplesttest, the Chi-square test and Fisher's exact test were performed to analyze differences in the demographic and clinical-pathological data between patients with normal and high NLRs. The Kaplan-Meier method was used for survival analysis. Potential prognostic factors for patients' outcome and tumor recurrence were analyzed using the log-rank test in univariate analysis. Statistically significant factors were then analyzed using a multivariate Cox regression model to determine whether they were independent. Thereafter, the patients were divided into four study groups according to the NLR value and the Hangzhou criteria. A Kaplan-Meier method for survival analysis was used to compare the recurrence-free survival (RFS) and OS rates among the groups. Based on the results, a new set of criteria combining both Hangzhou criteria and elevated NLR was established, and a ROC analysis was done to assess the validity of these new criteria. APvalue of <0.05 was considered statistically significant; 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. was increased to 3.994, the sensitivity was 54.3% and the specificity was 80.6%. Therefore, we chose an NLR >4 to define the group of patients with elevated NLR.

Comparison of the groups with different NLRs

The patients were categorized into a normal NLR group (n=108, 35.4%) and an elevated NLR group (n=197, 64.6%). As shown in Table 1, the majority of the baseline characteristics of the two groups were not significantly different; more patients in the elevated NLR group had more advanced tumors: tumor number >3, largest tumor >5 cm, total tumor size >8 cm and the presence of vascular invasion.

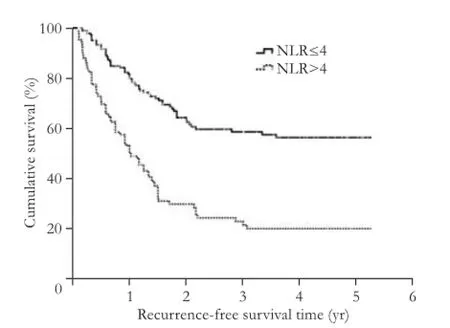

The patients with elevated NLRs experienced worse outcomes than those with normal NLRs. The RFS rates of the elevated NLR group at 1, 3 and 5 years were significantly lower than those of the normal NLR group

Table 1. Comparison of demographic and clinicopathological data of patients with HCC classified according to the NLR

Results

Patient characteristics and outcomes

Of 408 recipients, 103 were excluded from this study: 18 were HBV-unrelated, 4 were under 18 years old, 6 presented with preoperative sepsis, 4 had massive gastrointestinal tract bleeding, 15 had hypersplenism, 15 had no preoperative blood records, 10 lacked assessment of tumor characteristics, 17 did not have a pathologic diagnosis of HCC, and 14 died within one month after transplantation. Of the 305 patients included in our study, 122 (40.0%) experienced tumor recurrence. Of 159 (52.1%) deaths, 111 were due to tumor recurrence. The 1-, 3- and 5-year RFS rates were 75.3%, 48.2% and 46.0%, respectively. The OS rates were 72.8%, 42.2% and 38.4%, respectively. The mean survival time was 4.8 years (95% CI: 4.2-5.4).

The optimal cut-off value for NLR

Fig. 1. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis curve showing the effect of NLR on the recurrence-free survival of patients with HCC.

A ROC curve analysis was performed to determine the optimal cut-off value for an increased NLR. A ratio of 3.64 was associated with the highest sensitivity (61.4%) and specificity (77.0%), with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.717 (0.659-0.775). When the cut-off ratio(50.1%, 21.7% and 20.2% vs 80.5%, 58.7% and 56.4%, respectively;P<0.001; Fig. 1). Similarly, the patients with elevated NLRs had lower OS rates at 1, 3 and 5 years than those with normal NLRs (60.8%, 27.0% and 22.5% vs 78.4%, 51.1% and 47.8%, respectively;P<0.001; Fig. 2). The estimated mean survival time of the patients with elevated and normal NLRs were 3.3 years (95% CI: 2.4-4.1) and 5.6 years (95% CI: 4.8-6.4), respectively.

Risk factors for the mortality of patients with HCC who underwent LT

Fig. 2. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis curve showing the effect of NLR on the overall survival of patients with HCC.

Table 2. Univariate analysis of the effects of clinicopathological factors on recurrence-free survival of patients with HCC after LT

Univariate analysis demonstrated that six factors including NLR >4 were significant predictors of tumor recurrence. The other factors were AFP >400 μg/L, largest tumor size >5 cm, total tumor size >8 cm, the presence of vascular invasion and a differentiation grade of 3 to 4 (Table 2). Multivariate analysis showed that only four factors, including elevated NLR (HR=1.703,P=0.034), AFP >400 μg/L (HR=2.083,P=0.007), total tumor size>8 cm (HR=1.496,P=0.005) and the presence of vascular invasion (HR=2.202,P=0.003) were significant predictors of HCC recurrence after LT (Table 3).

The six factors listed above were also significantly associated with survival after LT (Table 4). However, only vascular invasion (HR=1.843,P=0.015) and differentiation grade 3 to 4 (HR=1.774,P=0.022) were independent factors significantly associated with OS after LT (Table 5).

Table 3. Multivariate analysis of the effects of clinicopathological factors on recurrence-free survival of patients with HCC after LT

Table 4. Univariate analysis of the effects of clinicopathological factors on overall survival of patients with HCC after LT

Establishment of new criteria based on the NLR and the Hangzhou criteria

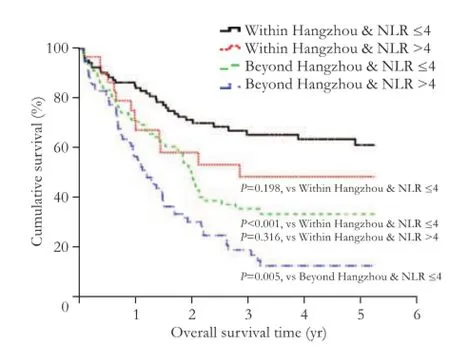

The patients were divided into four groups based on NLR and the Hangzhou criteria. The patients who did not fulfill the Hangzhou criteria and had elevated NLRs had the lowest RFS and OS rates compared with the other three groups (Figs. 3 and 4). On the contrary, the patients who fulfilled the Hangzhou criteria and hadnormal NLRs had the highest RFS and OS rates compared with those in the other three groups. The mean RFS and OS of the patients who fulfilled the Hangzhou criteria and had elevated NLR tended to be higher than that of the patients who did not fulfill the Hangzhou criteria and had normal NLR, although this difference was not significant. The NLR did not significantly affect the OS rate in the patients within the Hangzhou criteria (Fig. 4).

Table 5. Multivariate analysis of the effects of clinicopathological factors on overall survival of patients with HCC after LT

Fig. 3. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis curve showing the recurrence-free survival of HCC patients after LT.

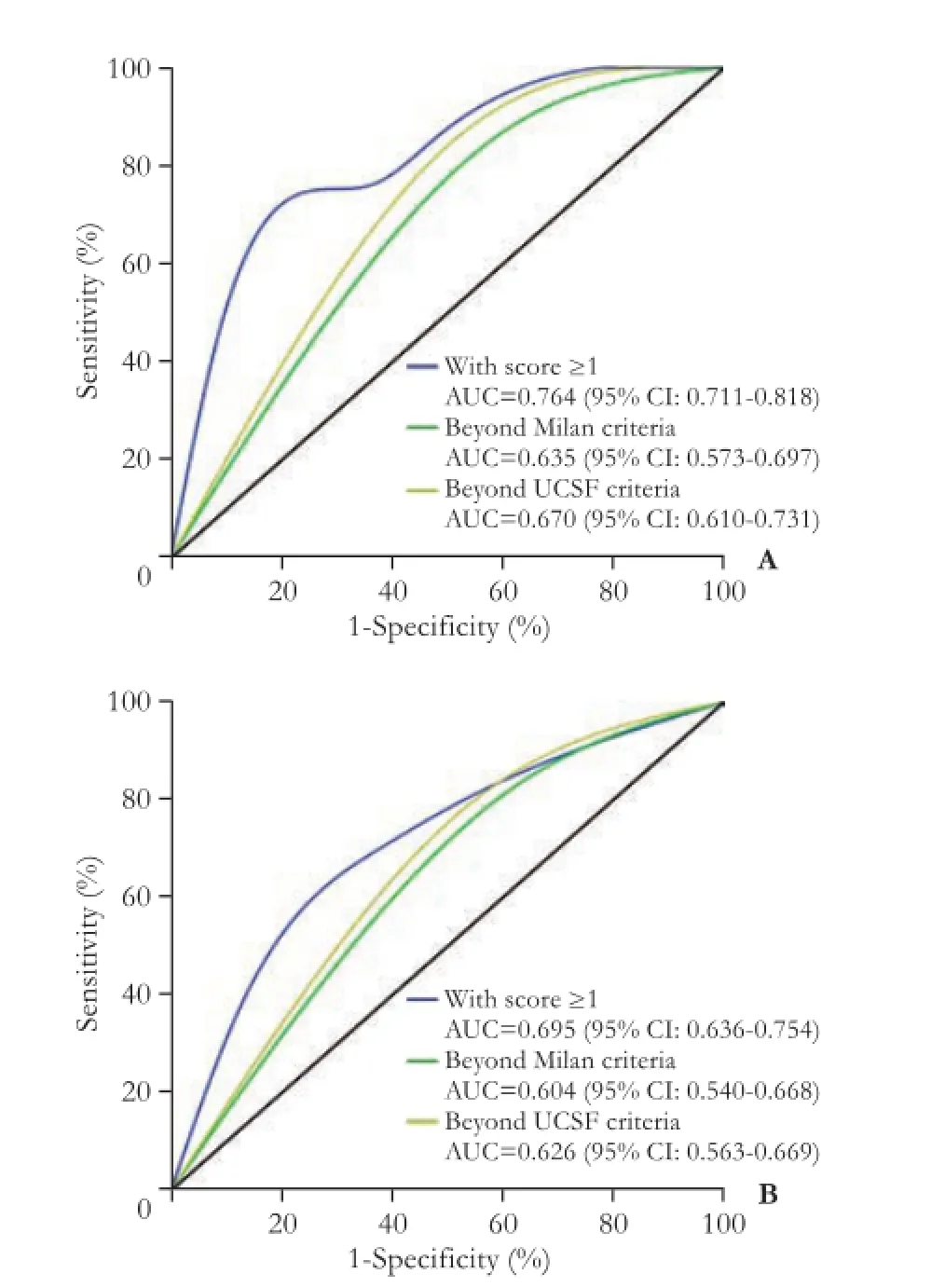

Based on the previous analysis, we developed a new set of criteria consisting of both the NLR and the Hangzhou criteria. An NLR >4 or beyond the Hangzhou criteria each counts for 1 point. Therefore, 0 point indicates that the patient is within the Hangzhou criteria and has a normal NLR. One point means that the patient is within the Hangzhou criteria but the NLR>4; or the patient has normal NLR but the tumor is beyond the Hangzhou criteria. Two points indicate that the patient neither fulfills the Hangzhou criteria nor has normal NLR. ROC analysis demonstrated that the patient with scores ≥1 had AUCs of 0.764 (95% CI: 0.711-0.818) for RFS and 0.695 (95% CI: 0.636-0.754) for OS (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. The comparison of ROC among the Milan, UCSF and the new criteria (the Hangzhou criteria plus NLR) A: The recurrencefree survival of HCC patients received LT; B: The overall survival of HCC patients who had undergone LT.

Fig. 4. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis curve showing the overall survival of HCC patients after LT.

Discussion

Since the adoption of the Milan criteria for selecting appropriate candidates with HCC for LT, the 4-year survival rate has increased significantly from 40% to 75%.[1,22,23]However, some of the patients with larger tumor burdens (>5 cm) have satisfactory post-LT outcomes[24]and thus, the so-called expanded criteria, such as the UCSF, Hangzhou and up-to-seven criteria are universally recognized. These expanded criteria allow some patients beyond the Milan criteria to receive LT. The Hangzhou criteria, which are well accepted in China, expand 37.5% more patients eligible for LT during a certain period.[5,25]However, the expansion of the selection criteria increases not only the risk of tumor recurrence,[20]but also the demand for donor organs. The limited number of organ donors prolongs patients' waiting time, resulting in poorer outcomes and a higher risk of severe complications, which render these patients no longer suitable candidates for LT. The previous criteria of selecting the proper transplant candidates primarily focused on tumor size and tumor number which were estimated by means of preoperative radiographic imaging. These estimations are not always accurate because of complications such as cirrhosis or the misdetection of microvascular invasion and tumor satellites. It has been reported that in approximately 30% of HCC cases, the tumor grade was underestimated based on preoperative CT or MRI.[26]Therefore, a noninvasive, easily obtainable and efficient biomarker should be added to the expanded criteria.

As an inflammatory marker, the NLR is easily obtained during routine preoperative testing. Recent studies[13,16,27,28]demonstrated the prognostic value of NLR for patients with HCC receiving standard treatments, including curative hepatectomy, transarterial chemoembolization, radiofrequency ablation and LT. We used a ROC curve analysis to select a cut-off point for elevated NLR, and we identified that an NLR >4 was an independent predictor for tumor recurrence of the patients with HCC undergoing LT. Our results were consistent with those of Yoshizumi's study.[16]Other studies[14,17,29,30]also confirmed the predictive value of an elevated NLR with different cut-off lines. Our study demonstrated that NLR was associated with the number of tumors, the size of the largest tumor, the total tumor size and the presence of vascular invasion. These factors are well-established predictors of prognosis described in our previous study.[31]The present study further confirmed that NLR was a predictor of tumor recurrence.

The exact mechanism of the elevation of NLR in patients with HCC and its correlation with a poor outcome remains unclear; several hypotheses may be suggested. First, neutrophils are recognized as a source of vascular endothelial growth factor, which has been associated with a poor prognosis among patients with HCC.[32]Cytokines and inflammatory mediators such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-17, which cause elevations in the levels of circulating neutrophils, are highly expressed in tumors and peritumoral tissues.[33-35]Second, a decreased lymphocyte count reflects an impairment of the host immune surveillance in patients with HCC. Unitt et al[36]reported that reduced lymphocytic infiltration was an independent predictor for post-transplant tumor recurrence among patients with HCC. Furthermore, Kim et al[37]demonstrated the diagnostic value of NLR in patients with uterine sarcoma, suggesting that the NLR can be used for the prognosis and diagnosis of the tumor. Some authors also suggested that gastric cancer patients with elevated preoperative NLR had poorer outcomes than those with normal NLR.[38]

Based on the results and the literature above, we developed a new set of preoperative criteria that combine the Hangzhou criteria and NLR. An elevated NLR and failure to fulfill the Hangzhou criteria each add 1 point to a patient's score. Patients with a score of 0 had the best outcome after LT. The higher the score, the poorer the patients' outcome. Patients with a score of 2 had the worst outcome, which indicates that these patients are not appropriate candidates for LT. Our results also demonstrated that these criteria were superior to the Milan and UCSF criteria for selecting candidates for LT. These new criteria combining the Hangzhou criteria with elevated NLR are proposed to be the main criteria for the selection of LT candidates with HCC in the mainland of China.

The prognostic value of NLR for the outcome of patients with HCC after LT is well recognized. In addition to the tumor itself, other conditions such as undetected inflammation and preoperative loco-regional treatment can elevate the NLR, which overestimate the disease severity. In addition, most of our HCC cases were HBV-related, which may limit the application of these new criteria because HCV infection and alcohol abuse are responsible for most cases of HCC in Western countries and Japan. Our results demonstrated that the tumor recurrence rate was higher than that reported elsewhere. We believe that it can be attributed to the following factors: First, the time span of this retrospective study was too long. Second, in the early period there were no widely unified criteria for the selection of HCC patients for LT in the mainland of China, some patients with advanced HCC also underwent LT. Retrospective nature is a limitation of this study. Therefore, prospective research is needed to validate the feasibility of these new criteria.

In conclusion, the preoperative elevated NLR hadadverse impact on prognosis of patients with HCC after LT. The criteria combining the Hangzhou criteria with an elevated NLR can be used to select patients with HCC for LT.

Contributors:XGQ and YLN proposed the study. XGQ and YJY collected and analyzed the data, followed up with the patients and wrote the first draft. YJY and YLN revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. YLN is the guarantor.

Funding:This study was supported by grants from the National Science and Technology Major Project of China (2012ZX10002-016 and 2012ZX10002-017).

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our hospital.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2012;379:1245-1255.

2 Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61:69-90.

3 Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 1996;334:693-699.

4 Yao FY, Ferrell L, Bass NM, Watson JJ, Bacchetti P, Venook A, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: expansion of the tumor size limits does not adversely impact survival. Hepatology 2001;33:1394-1403.

5 Zheng SS, Xu X, Wu J, Chen J, Wang WL, Zhang M, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Hangzhou experiences. Transplantation 2008;85:1726-1732.

6 Jonas S, Bechstein WO, Steinmüller T, Herrmann M, Radke C, Berg T, et al. Vascular invasion and histopathologic grading determine outcome after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis. Hepatology 2001;33:1080-1086.

7 Sherman M. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology, surveillance, and diagnosis. Semin Liver Dis 2010;30:3-16.

8 Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature 2002;420:860-867.

9 Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature 2008;454:436-444.

10 Oh BS, Jang JW, Kwon JH, You CR, Chung KW, Kay CS, et al. Prognostic value of C-reactive protein and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2013;13:78.

11 Mano Y, Shirabe K, Yamashita Y, Harimoto N, Tsujita E, Takeishi K, et al. Preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is a predictor of survival after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective analysis. Ann Surg 2013;258:301-305.

12 Fu SJ, Shen SL, Li SQ, Hua YP, Hu WJ, Liang LJ, et al. Prognostic value of preoperative peripheral neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma after radical hepatectomy. Med Oncol 2013;30:721.

13 Gomez D, Farid S, Malik HZ, Young AL, Toogood GJ, Lodge JP, et al. Preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic predictor after curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg 2008;32:1757-1762.

14 Halazun KJ, Hardy MA, Rana AA, Woodland DC 4th, Luyten EJ, Mahadev S, et al. Negative impact of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio on outcome after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg 2009;250:141-151.

15 Limaye AR, Clark V, Soldevila-Pico C, Morelli G, Suman A, Firpi R, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio predicts overall and recurrence-free survival after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res 2013;43:757-764.

16 Yoshizumi T, Ikegami T, Yoshiya S, Motomura T, Mano Y, Muto J, et al. Impact of tumor size, number of tumors and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in liver transplantation for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res 2013;43:709-716.

17 Bertuzzo VR, Cescon M, Ravaioli M, Grazi GL, Ercolani G, Del Gaudio M, et al. Analysis of factors affecting recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation with a special focus on inflammation markers. Transplantation 2011;91:1279-1285.

18 Wang GY, Yang Y, Zhang Q, Li H, Chen GZ, Yi SH, et al. Preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic predictor after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2011;91:1519-1522.

19 Lei J, Yan L. Outcome comparisons among the Hangzhou, Chengdu, and UCSF criteria for hepatocellular carcinoma liver transplantation after successful downstaging therapies. J Gastrointest Surg 2013;17:1116-1122.

20 Gao T, Xia Q, Qiu de K, Feng YY, Chi JC, Wang SY, et al. Comparison of survival and tumor recurrence rates in patients undergoing liver transplantation for hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma using Milan, Shanghai Fudan and Hangzhou criteria. J Dig Dis 2013;14:552-558.

21 Jiang L, Yan LN. Current therapeutic strategies for recurrent hepatitis B virus infection after liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol 2010;16:2468-2475.

22 Iwatsuki S, Marsh JW, Starzl TE. Survival after liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Princess Takamatsu Symp 1995;25:271-276.

23 Selby R, Kadry Z, Carr B, Tzakis A, Madariaga JR, Iwatsuki S. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg 1995;19:53-58.

24 Kim JM, Kwon CH, Joh JW, Kim SJ, Shin M, Kim EY, et al. Patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma beyond Milan criteria: should we perform transarterial chemoembolization or liver transplantation? Transplant Proc 2010;42:821-824.

25 Lei JY, Wang WT, Yan LN. Hangzhou criteria for liver transplantation in hepatocellular carcinoma: a single-center experience. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;26:200-204.

26 Silva M, Moya A, Berenguer M, Sanjuan F, López-Andujar R, Pareja E, et al. Expanded criteria for liver transplantation in patients with cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl 2008;14:1449-1460.

27 Huang ZL, Luo J, Chen MS, Li JQ, Shi M. Blood neutrophilto-lymphocyte ratio predicts survival in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing transarterial chemoembolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2011;22:702-709.

28 Chen TM, Lin CC, Huang PT, Wen CF. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio associated with mortality in early hepatocellular carcinoma patients after radiofrequency ablation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;27:553-561.

29 Lai Q, Castro Santa E, Rico Juri JM, Pinheiro RS, Lerut J. Neutrophil and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio as new predictors of dropout and recurrence after liver transplantation for hepatocellular cancer. Transpl Int 2014;27:32-41.

30 Wang GY, Yang Y, Li H, Zhang J, Jiang N, Li MR, et al. A scoring model based on neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts recurrence of HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation. PLoS One 2011;6:e25295.

31 Zhang Q, Chen X, Zang Y, Zhang L, Chen H, Wang L, et al. The survival benefit of liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma patients with hepatitis B virus infection and cirrhosis. PLoS One 2012;7:e50919.

32 Brodsky SV, Mendelev N, Melamed M, Ramaswamy G. Vascular density and VEGF expression in hepatic lesions. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2007;16:373-377.

33 Araki K, Kishihara F, Takahashi K, Matsumata T, Shimura T, Suehiro T, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma producing a granulocyte colony-stimulating factor: report of a resected case with a literature review. Liver Int 2007;27:716-721.

34 Motomura T, Shirabe K, Mano Y, Muto J, Toshima T, Umemoto Y, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio reflects hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver transplantation via inflammatory microenvironment. J Hepatol 2013;58:58-64.

35 Zhu XD, Zhang JB, Zhuang PY, Zhu HG, Zhang W, Xiong YQ, et al. High expression of macrophage colony-stimulating factor in peritumoral liver tissue is associated with poor survival after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:2707-2716.

36 Unitt E, Marshall A, Gelson W, Rushbrook SM, Davies S, Vowler SL, et al. Tumour lymphocytic infiltrate and recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma following liver transplantation. J Hepatol 2006;45:246-253.

37 Kim HS, Han KH, Chung HH, Kim JW, Park NH, Song YS, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio for preoperative diagnosis of uterine sarcomas: a case-matched comparison. Eur J Surg Oncol 2010;36:691-698.

38 Graziosi L, Marino E, De Angelis V, Rebonato A, Cavazzoni E, Donini A. Prognostic value of preoperative neutrophils to lymphocytes ratio in patients resected for gastric cancer. Am J Surg 2015;209:333-337.

Received May 25, 2014

Accepted after revision March 9, 2015

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Gut microbiota and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- Risk factors of metabolic syndrome after liver transplantation

- Warm HTK donor pretreatment reduces liver injury during static cold storage in experimental rat liver transplantation

- Intrahepatic distant recurrence following complete radiofrequency ablation of small hepatocellular carcinoma: risk factors and early MRI evaluation

- Oncogenic role of microRNA-423-5p in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Ankaflavin ameliorates steatotic liver ischemiareperfusion injury in mice