THE STEPPE FRONTIERS OF PĀRSA:NEGOTIATING THE NORTHEASTERN BORDERLANDS OF THE TEISPID-ACHAEMENID EMPIRE*

2024-01-12MarcoFerrario

Marco Ferrario

University of Trento / University of Augsburg

1.Introduction: a history of violence

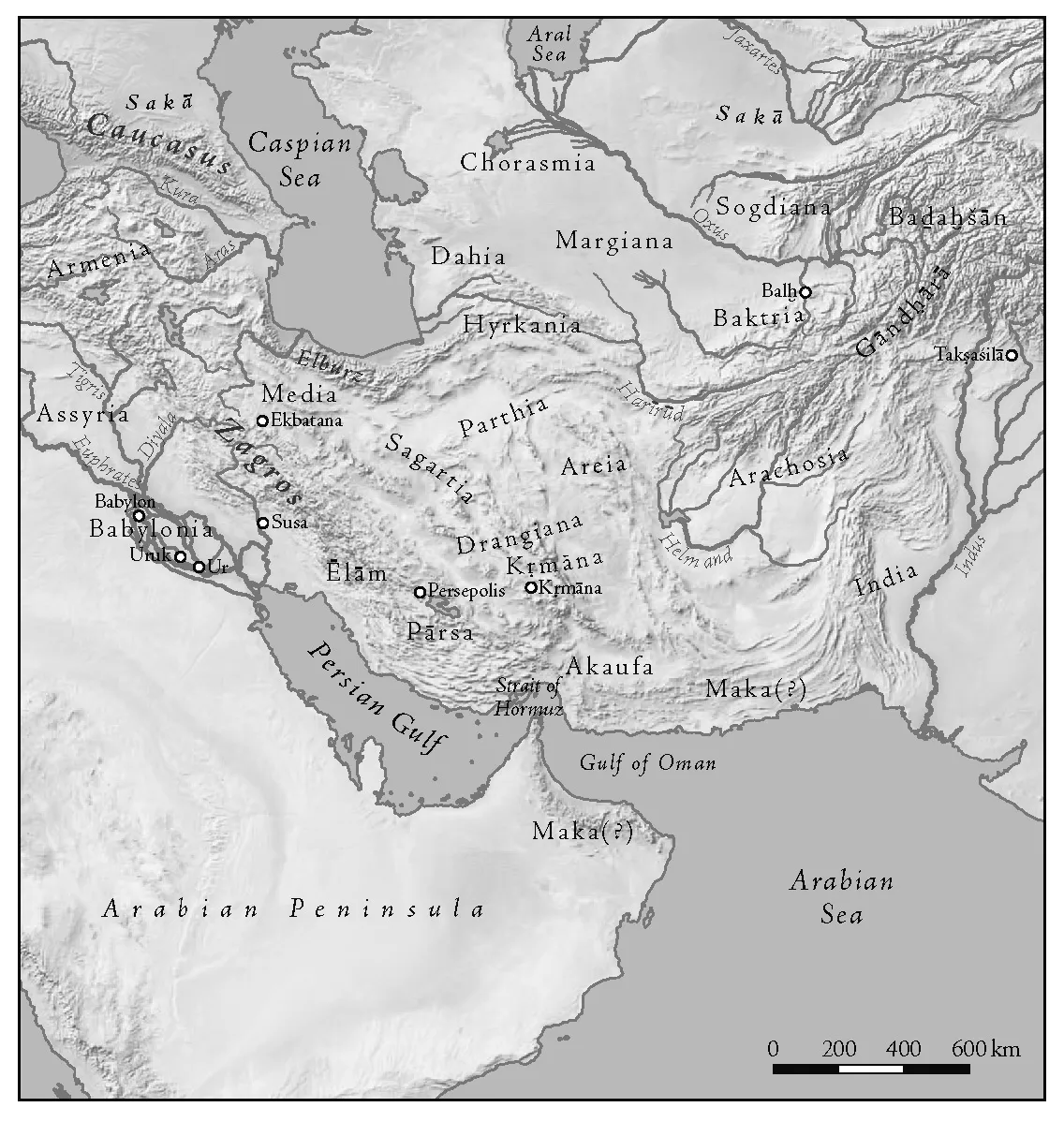

In the eyes of both ancients and moderns, the Central Asian frontier zone(s) of the Achaemenid Empire, here understood as the satrapies of Baktria, Sogdiana,Chorasmia,andthe semi-desertic steppes to their north, has traditionally assumed the features of a liminal territory characterized by geopolitical instability and cultural alienation.3It is worth emphasizing that we are not dealing with an isolated case.A very influential (albeit debated) interpretation of a(nother) northern imperial frontier – again with the steppe world – in similar terms was proposed by Barfield 1989.For an overview of Eastern Īrān in Achaemenid times,see now Stark 2021; Bichler 2020 for an insightful study on narrative and liminal space (the borders of the – known – world) in Хenophon’s writings.Herodotos’ account of Kyros’ campaign against theSakā(Hdt.1.201–216), in which the founder of the Empire met his death, constitutes a founding moment in the history of this imagery of Central Asia and its inhabitants.4Bichler 2021 provides a detailed study of Herodotos’ narrative of Kyros’ death in Central Asia and of its Fortleben.Chiai 2021 is a useful overview of ethnography and historiography on the (Black Sea) Sakā in Archaic Greece (ibid., 201–202 he briefly discusses the Achaemenid written evidence,mostly from the inscriptions).Indeed: recently argued, Herodotos constitutes an interpretative problem for the entire history of the Achaemenid Empire, starting from its beginnings; it follows that a certain amount of skepticism about his version of Kyros’ death is at least legitimate.5Anderson 2020, 586: “Herodotos is a problem for the entire Persian Empire.”Nevertheless, as some recent studies have shown, there is reason to believe not only that Herodotos’ version of the events surrounding Kyros’ Central Asian expedition is preferable to another tradition circulating in antiquity (and echoed, for example, by Хenophon).6Note Vlassopoulos 2017 and, somewhat more skeptically, Degen 2020 on Хenophon’s Persian ethnography.Following such an account, the conqueror would have died in his bed, having subjugated almost the entire world then known.7Cf.Kuhrt 2021 with previous literature.

As convincingly argued by Robert Rollinger and Julian Degen, in fact, a careful reading of paragraphs 71–76 of the Bīsutūn inscription (column V,reporting on Darius’ expedition against the pointy-hattedSakā) that pays due attention to the Near-Eastern precedents of this crucial text, suggests that the specter of Kyros’ expedition – and its dramatic conclusion – was haunting the Empire’s territories and occupying the minds of its (would-be) ruling class still years after the events.8Rollinger and Degen 2021a.In the light of the prominent role played, for example, in the religious landscape of Pārsa in the critical phase of the Ēlāmo-Īrānian acculturation (cf.especially Henkelman 2008; 2018; 2021b), it would be worth explore in more depth how Ēlāmite kings represented mountain people (see, for example, Balatti 2017, 135–150) in their inscription and self-representation strategies of rulership, for the impact of Achaemenid royal ideology of such discourses might be much more far ranging than hitherto assumed.

In particular, the exceptional importance ascribed by Darius to the passing of a body of water (which in the Herodotean narrative marks Kyros’ crossing of a natural and human, if not divine, threshold, therefore heralding his ruin) and the subsequent subjugation of theSakacommander Skunḫa – whose inclusion in the Bīsutūn relief along with the other so-called “liar kings” prompted the almost complete remaking of the entire inscription – leads to the conclusion that the representation of Darius’ final triumph in thelongus et unus annusthat sanctioned his accession to the throne was shaped in constant dialogue with what was known (or remembered) at the time about Kyros’ last battle.9Waters 2014, 76.

In other words, the victory over theSakāsealed Darius’ triumph at the borders(ideological, if nothing else) of the inhabited world, where no one before him – not even the mighty Kyros – had either managed to venture or to successfully conquer.10See now Waters 2023 on the Teispid origin of the Empire and Minardi 2023 for a thorough overview of the Central Asian satrapies, including Sakā inhabited, if not controlled, territories.As a result, he provided himself with a powerful argument legitimizing his accession to the throne.11It must be remembered that such a move was moreover all the more necessary in a context such as the one in which the founder of the Achaemenid Dynasty came to power: cf.Schwinghammer 2011, as well as the recent Rollinger and Degen 2021b on the (re)foundation of the Empire after the death of Cambyses.Rollinger 2021 elaborates on the ideological significance of (especially, but not exclusively) natural borders in the broader Near Eastern world, of which long-standing tradition the Achaemenids were fully aware.Thomas 2017 provides an astute critical evaluation of the literary sources dealing with the (alleged) kings’ assassination and courtly intrigues: worth pointing out, however, is her emphasis on the succession dynamics as perhaps the only real threat, before Alexander, of course, for the empire’s stability.Additionally, the fact that the precedent of Kyros is constantly alluded to, but never explicitly mentioned in the inscription (for even his very name is left out in Darius’ very carefully crafted genealogy at the beginning of the text), implies that the death of the founder of the Empire in Central Asia set an uncomfortable precedent, from which it was necessary to distance oneself in a way that was both firm and subtle.In short, the affairs of Central Asia were capable – not only in the eyes of Greek authors – of influencing the succession policy of the largest (until then) empire in Eurasia.12Rollinger and Degen 2021a, 212.Cf.Beckwith 2023, 54–114 for the bold – but in the light of,among other things, its complete disregard of a growing body of evidence attesting to the pivotal role of the Ēlāmo-Īrānian background of the Persian (imperial) ethnogenesis, rather unconvincing – suggestion that, in fact, Darius’ accession ought to be seen as little more than the continuation of a“Scytho-Median” Empire.

2.Imperial enemies far away from Pārsa

The picture does not seem to change and indeed appears to worsen during the Achaemenid imperial trajectory.In the opinion of the Chinese historian and archaeologist Wu Хin – one of the most authoritative and committed proponents of this interpretative approach – the available evidence (including first-hand documentation such as Achaemenid seals) suggests that the Central Asian peoples, which is to say mainly, butnot only, theSakā, constituted a constant – and increasing – threat to the geopolitics of the northeastern satrapies,or at least were so presented within the imperial discourse of courtly élites.Consequently, given the importance of a region such as Baktria-Sogdiana (and Chorasmia) in the framework of the newly established polity, unrests in Central Asia might have affected the stability of the entire Empire, and this starting at the very least since the reign of Хerxes.13Cf.at great length Wu 2005, 287–320.

The persistence (and intensity) of these hostilities would, in Wu’s opinion, have profoundly shaped both Achaemenid politics in – and imagination of – Central Asia, to the point of elevating the local populations (and particularly theSakā) to the status of enemies of the Empire par excellence.As a consequence, over time the – repeated – military campaigns against them would have assumed a role of primary importance in the self-representation of the imperial ruling class.14Ead.2010, 559; 2014, 229–230.Cf., moreover, the remarks in Rollinger and Degen 2021a, 204.Sigillography, in particular, would suggest, according to this interpretation, that it was the imperial court itself that promoted the circulation of objects with a profound symbolic meaning and significant social capital (as seals undoubtedly were, especially those produced according to the norms of the so-called “court style”) depicting war scenes with Central Asian subject.The main goal of such a policy would have been to promote a sense of belonging to the Achaemenid political community in opposition to its enemies located at the borders of the world and specifically in Central Asia.15See the contributions by Richard Payne (e.g., 2015 and 2017) for a comparable strategy adopted by the Sāsānids once confronted with the steppe polities during the 5th century AD and Wu 2014 for a thorough discussion of the ideological politics behind the production and circulation of seals featuring warfare in (and against) Central Asia(ns).Such a policy can be understood as one of the strategies developed by empires to shape both central and regional élites according to the model recently put forward by Haldon 2021.Christopher Tuplin recently also came to similar conclusions after carrying out the most detailed study of Achaemenid war-related sphragistic evidence available to date.To put it in his own words,“it is probably safe to infer that fighting in Central Asia played a larger part in the Persianmonde imaginairethan one might suppose from the Greek historical tradition – and even that it did so because there was more actual fighting there than that tradition knows of.”16Tuplin 2020, 378.Emphasis in the original.

2.1.As things got worked out: old questions and new approaches

This essay aims to offer a different understanding of the dynamics underpinning the formation of the Achaemenid frontier zones in Central Asia and the mechanisms regulating the social, political, and economic relations that were structured in this area from the origins of the Empire itself throughout its entire historical evolution.17Cf.King 2021, 315–361 for a treatment of Achaemenid Baktria and its broader Central Asian environment in the 4th century BC.On the northeastern borders of the Empire, see also Minardi 2021.Daffinà 1967 can still be profitably read when it comes to the geography of mobile people across Central Asia (with a special focus on Drangiana).As it will be argued, the – still dominant – conception of the relations between the Persian imperial structure and the Central Asian peoples in predominantly (when notexclusively) warlike and oppositional terms does not adequately take into account the scholarly debate that has been going on for some years now, both in the field of studies on the nature and functioning of empires as socio-political, economic, and cultural entities from a comparative and world-historical perspective and, what matters most, within Achaemenid historiography.18On the histor(iograph)y of empires in a world historical and comparative perspective, see the seminal Scheidel and Morris 2009, Rollinger and Gehler 2014, and now Bang, Bayly and Scheidel 2021.On the Achaemenid Empire in its broader Near Eastern context, see Rollinger 2023 with bibliography.

More specifically, in the following pages, a key piece of evidence for the current interpretation of the Central Asian frontier of the Achaemenid Empire(stemming from Strabo’sGeography) will be investigated in the light of an interpretative model that takes adequate account of the complexity (both in geographical and socio-political terms) of the Central Asian space.19Payne and King 2020.

This complexity – what Bleda Düring and Tesse Stek have eloquently defined as “the practical situations on the ground” – on the one hand imposesstructurallimits on the political-administrative penetration and rationalizing action (to control and exploit men and resources) of an empire, not only in pre-modern times.20“Practical situations on the ground:” Düring and Stek 2018a, 10.This paper provides one of the best introduction to the issues and the topics of contemporary research around the Imperial Turn.On the other hand, and at the same time, it, however, also opens up room for maneuver to individuals and groups (mainly, but not exclusively, local élites)endowed with the social and ecological skills to exploit the opportunities that both the landscape itself and the establishment of imperial power in the space they lived in (and controlled) made available.21See Düring and Stek 2018a/b on the practical situations on the ground.On landscape as a social and historical actor on its own capable of conditioning the plans of imperial polities and officers, see King 2020 and already the path-breaking Scott 1998 (esp.ibid., 309–341).

In the specific case of Central Asia, not least because of the state of the available evidence, an investigation of this kind cannot neglect a comparative methodology that considers thelongue duréeof this region of Eurasia in an attempt to identifystructuralelements characterizing theImperial Experienceof the space under scrutiny here.22This is the approach (successfully) adopted by King 2020.On the sources available for Central Asia during the Achaemenid and the (post) Hellenistic period, see Rapin 2021 and Morris 2019a,respectively, with the references provided in Minardi 2023.The Imperial Experience: Bang, Bayly and Scheidel, W.2021, vol.I.Beckwith 2009 made a forceful case for giving people of what he calls Central Eurasia more agency in shaping world history from the Black Sea to the Pacific Ocean.

It is furthermore the purpose of this study to show how the traditional reading of the history of the Achaemenid borderlands (not only in Central Asia) in terms of opposition and conflict can be replaced by another, more profitable approach,which interprets the dynamics reflected in the sources as the result of mutual agreements interpreted differently by the involved players with the common aim of obtaining the maximum collective advantage from the interactions taking place on (and beyond) the imperial frontier areas.23See on this topic the compelling argument developed against the background of the Near Eastern longue durée in Rollinger and Degen 2021a, 200 and, for a very different perspective, Wu 2017 and 2018.

In line with the most recent developments in the historiography related to the so-calledImperial Turn, it is to be hoped that, at the end of this contribution,the process of (co-)construction of the Achaemenid imperial space (and of its borderlands) in and across Central Asia will emerge more clearly in terms of adialecticalrelationship, namely, as the intentional development of a space of confrontation and negotiation of (not always) converging interests that influenced decisively, while at the same time being no less significantly affected by, the surrounding environment.24For the theoretical framework which the standpoint outlined here relies upon, cf., e.g., Hämäläinen 2008, Hall 2021, and especially Rollinger 2023.After all, the famous concept of The Middle Ground was originally developed to describe precisely the kind of dynamics this section sought to outline; see White 22011, 52.As brilliantly pointed out by Michael Gehler and Rollinger, in fact, borderlands such as the Achaemenid Northeastern Central Asian satrapies are an area “where an empire’s ‘influence’ is ubiquitous,” and this is because its sheer infrastructural, political, social, and economic presence, with the contextual demands that this causes, triggers, releases, and provokes “complex processes of adaptation and adoption, resistance and integration, emulation and opposition, all of it at the very same time.”25Gehler and Rollinger 2022, 22 for this and the previous quote.This is perhaps the most sensitive description of the general theoretical framework of contemporary scholarship informed by theImperial Turn, which critically informs the understanding of Achaemenid borderlands underpinning the present paper.

With such considerations in mind, let then Strabo take us to (early) Achaemenid Central Asia.

3.Mirror, mirror on the wall, who’s the furthest of them all?

In the context of the description of the Central Asian territories crossed by Alexander the Great during the final stages of the conquest of the Northeastern territories of the Persian Empire (329–327See, e.g., Vacante 2012 and Howe 2016.BC), Strabo focuses on the siege – and subsequent pillage – of a cluster of settlements at the very outskirts (ἔν τε τῇ Bακτριανῇ καὶ τῇ Σoγδιανῇ) of the Achaemenid domains.Among them,particular importance in the – albeit concise – narrative of the geographer from Amasya assumes Kyropolis (τὰ Kῦρα), which Strabo locates along the banks of the river Iaxartes (today’s Syrdaryo) and bluntly describes as “the last – in the double chronological and spatial sense – foundation of Kyros” as well as an outpost (ὅριoν: that is, limit, border, and, by extension, stronghold) of Persian power.26Strab.11.11.4: καὶ τὰ Kῦρα, ἔσχατoν ὂν Kύρoυ κτίσμα ἐπὶ τῷ Ἰαξάρτῃ πoταμῷ κείμενoν, ὅπερἦν ὅριoν τῆς Περσῶν ἀρχῆς.See Cohen 2013, 254 for further bibliography and Rapin 2018a for the – still debated – localization of the settlement.

Due in no small part to the campaign of Alexander himself, who struggled to impose his authority (which was, moreover, ephemeral, and the result of exhausting negotiations with local rulers) in those territories, this fleeting remark by Strabo has played a critical role in the reconstruction of the sociopolitical dynamics characteristic of the Central Asian frontier zones both in the late Achaemenid period and, in retrospect, throughout the entire span of Persian imperial hegemony in Central Asia.27Traditionally located in the territory of today’s Хuçand (Хyҷaнд, in Taǧikistān), Kyropolis is believed to have been erected in a strategic position, controlling an imposing waterway and an ecological frontier (an ecotone) with the steppe world, with the intention on the part of the Achaemenid administration of securing its northern border(s) in a politically very sensitive area, constantly threatened as it was by incursions led bySakāpeople.28Cf., e.g., the discussion in Holt 1988, 11–52; 2005, 1–66 (on Alexander’s inheritance of the Achaemenid border, on which see now Rollinger and Degen 2021c); Wu 2017.On empire and ecology in a world-historical perspective, see, most recently, Beattie and Anderson 2021.

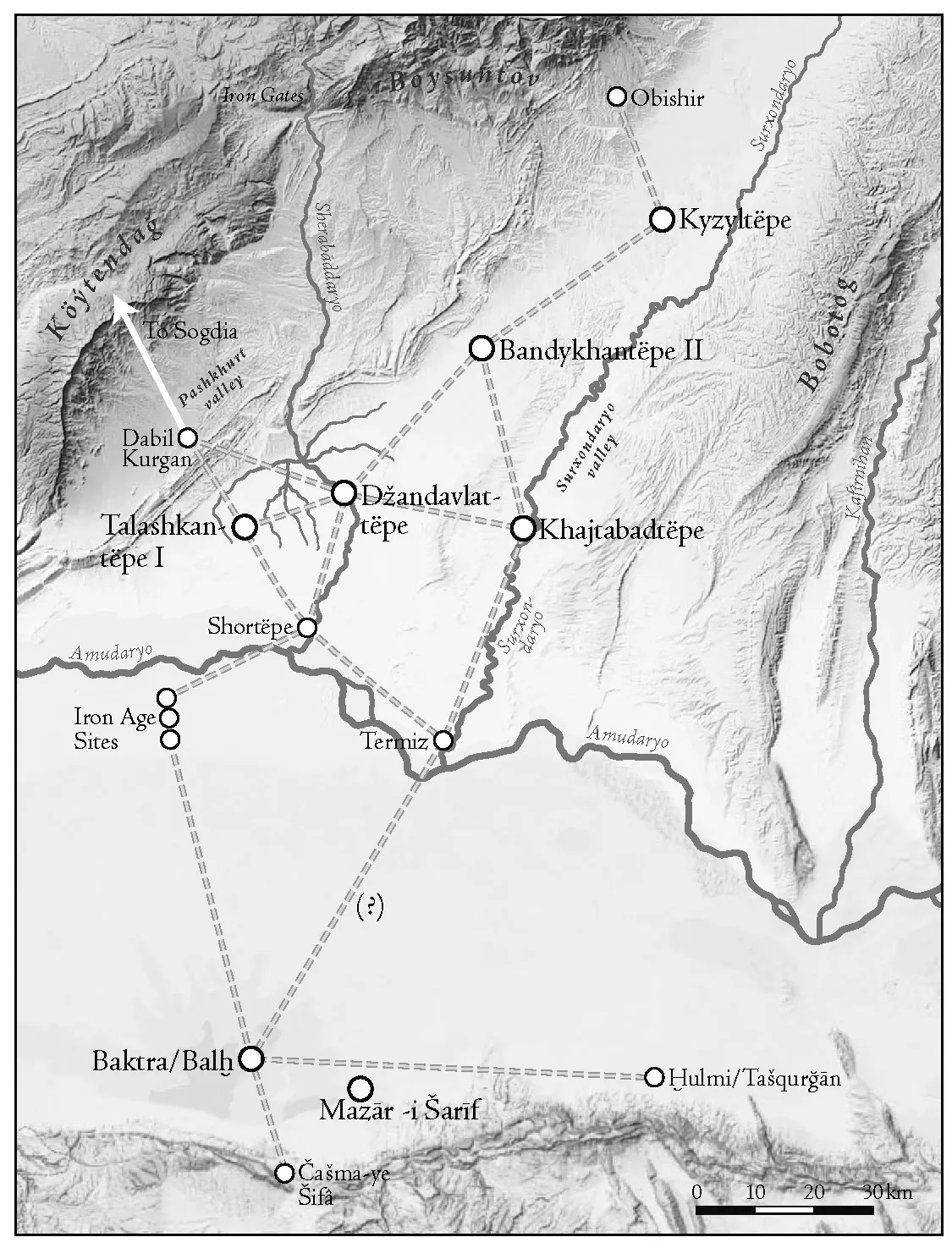

Kyros’ fateful expedition recounted by Herodotos, in this scenario, would only confirm the precariousness of Persian power along the Central Asian frontier(s)and the consequent need for a massive armed intervention, which nevertheless ended in catastrophe.Although still debated, the more recent identification of the settlement mentioned by Strabo at the site of Nurtepe, in the territory of today’s Jizzax (Жиззax in Uzbekistān), while on the one hand contributing to more precise cartography of (late) Achaemenid Central Asia, on the other hand in no way changes the interpretation of the passage in theGeography, and might even be taken as further corroborating it.29This new identification is the result of a detailed re-examination of the historiographic sources in the light of the archaeological, topographical, and linguistic investigation carried out over the last few decades, in particular by Claude Rapin: cf.Rapin 2018a, 264 and Goršenina and Rapin 2020 for an overview of the debate.Rapin 2021 deals specifically with the Achaemenid period.This said, of course, it should never be forgotten that specifically Greek (and Roman) spatial categories and understandings of the Persian world crook into our extant accounts of the Empire’s geography:Bichler 2006; 2020.Located north of a gorge (which later became famous under the name of Tīmūr’s Gates orTimur Darvaza) connecting the site of modern Samarqand – the Achaemenid Afrāsyāb/Marakanda mentioned among others, by Strabo himself – with the Farġānẹ valley (thus already in a territory with a high density ofSakāpopulation), Nurtepe/Kyropolis, not unlike other crucial sites in Achaemenid Central Asia such as Kyzyltepe (in presentday Surxondaryo) or Koktepe (the most crucial settlement in Sogdiana before the imperial mandated expansion of Marakanda) would have been devised with the primary intention of controlling the movements of the pastoral populations and, if necessary, launching from there intimidating actions, not unlike those that saw the entire Makedonian general staff engaged during Alexander’s Sogdian campaign.30See, beyond Strab.11.11.4, Arr.Anab.3.30.6 and Curt.7.6.10.Cohen 2013, 279–282 provides previous bibliography on the history of the site.Cf., most recently, Rapin 2017 on Koktepe; 2018a,263–271 on Marakanda, and Wu, Sverčkov and Boroffkam 2017 for a detailed report on Kyzyltepe(with the discussion in Wu 2020).

3.1.The presumptive satrapy: Kyropolis and the art of being governed

Faced with this reconstruction, it will be worth developing some methodological considerations that seem to undermine its assumptions, in order to introduce,in the next section, the comparative evidence necessary, as the forthcoming discussion seeks to show, to frame Strabo’s passage in a broader (and more fitting) Central (Eur)Asian context that allows appreciating in all its implications both what the geographer says and, above all, what the text of his work glosses over.31Cf.the methodological remarks in Scott 1998, 11–52.

First, authoritative studies undertaken in recent years have shown that, beyond the ideological and literary agenda of a specific author, Greek (and following in their footsteps Latin) historiography – not to mention geographical inquiry – on Achaemenid subjects is deeply influenced by mental maps.Which is to say,our written evidence often heavily (although not explicitly) relies on the corresponding worldview, in both the physical and figurative sense, produced within the Persian world and not infrequently by the narrower circles around the Great King and his court.32Rapin 2018b and Rollinger and Degen 2021a, 207–214 for a thorough discussion on this topic.It follows that, even in the case of Strabo, his understanding of thegenesis(and even more so of thefunction) of a settlement such as Kyropolis is in no small measure indebted to a discourse –sensuFoucault – on power and empire functional to the consolidation of the same by the Persian ruling class, if not by Darius himself in the broader context of his project of imperial (re-)foundation.33On the Foucaultian concept of ordre du discours, see Foucault 2004.Rollinger 2014a/b on Darius as the promoter of a new discourse on power and empire (with particular emphasis on the staging of the former at the furthermost ends of his domains).See now also Rollinger and Degen 2021b on the Achaemenid Empire after Cambyses’ death.The most obvious implication of the above is that a reading in merely adversarial terms of the foundation of a settlement such as Kyropolis can (or should)notbe accepted without further critical scrutiny.

Second, to claim, as Strabo does, that Kyros’ last foundation on the Iaxartes embodied “the limit of Persian power” (ἦν ὅριoν τῆς Περσῶν ἀρχῆς) is to assumea priorithe existence of a Persian power capable of fulfilling the tasks, anything but trivial, to which, in Strabo’s (and of later interpreters’) understanding,a settlement such as Kyropolis was assigned.34Strab.11.11.4: trans.is my own.Cf.the LSJ (p.1251 s.v.) and the trans.by Jones 1928, 283.It is worth noting that this conclusion is by no means self-evident.On the contrary, it seems to assume a scenario much more consistent with the time of Darius, when the complex administrative and bureaucratic apparatus developed overseveral decadesin order to control the territory, the resources, and the population of the heart of the Empire (roughly corresponding to today’s Īrānian province of Fārs), had already taken several decades to run in, and adapt to, the various local contexts of the immense realm.35Henkelman (2017) has called such impressive administrative system the Achaemenid “Imperial Paradigm.” See most recently Henkelman 2021a with previous bibliography and the path-breaking Henkelman 2017.However,noneof this can be taken for granted at the time of Kyros, when the whole infrastructure of imperial control and exploitation was still being developed and, even more crucially, adapted to the very different geographic and anthropic contexts of the newly conquered territories, a process which, through imperial history, more often than not is carried out based on trials and errors.36Düring and Stek 2018a.To rule an empire, in short, one must first conquer it.37Kuhrt 2021.

Third, a strict interpretation of Strabo’s passage – that is, one that considers it exclusively, or even onlyin bonam partem, as a document ofactual geographyand not as acultural construct– almost entirely obliterates the local context and the constraints it must have imposed on an empire, albeit endowed with formidable means of coercion, still in its dawning phase and consequently much less capable of affirmative action than its representatives were prepared to admit,if not to themselves, undoubtedly to their interlocutors.38See Rollinger and Degen 2021a, 205 for the distinction between real geography on the one hand, and mental mapping (and ideological discourse) on the other.On the structurally conditioned nature of pre-modern empires, see Burbank and Cooper 2021 and Khatchadourian 2016, 1–24 (on the Achaemenid case with additional remarks by Briant 2020 – on Central Asia – and 2021 – more generally on the dynamics of Persian universal rule).Seth Richardson’s meticulous examination of the proclamations of conquest (and subsequent control of the claimed territory) by ancient Mesopotamian rulers has, for example, shown how such “imperial fantasies,” far from celebrating a political-military triumph,were in not infrequent cases thepremiseof the political affirmation that they imply as havealreadybeen accomplished.39Garrison 2011 on “imperial fantasies” with a thorough assessment of the written and visual program of the Bīsutūn inscription.In the poignant words of James C.Scott (2009, 34), “if we take the cosmological bluster emanating from the court centers as indicative of facts on the ground, we risk … ‘imposing the imperial imaginings of a few great courts on the rest of the region.’”

The geopolitical framework implicit in Strabo’s description of Kyropolis (and the socio-economic one, which the geographer deliberately disregards) presents as agivenwhat must have been, in Kyros’ time, a long, arduousprocess, subject to constant negotiation on the part of all the actors involved in it (thus, in addition to theSakāpopulations, also the Baktrians, the Sogdians, and the Chorasmians,who had sustained contacts with the steppe world centuriesbeforethe rise of Persian power in Central Asia).40Minardi 2015 provides an in-depth study of the relationships between Chorasmia (and through it, Baktria, on which during the Achaemenid period see now Gzella 2021) with the world of the Eurasian steppe on the one hand and, on the other, with Persian power.On the rise of Sakā power in Central Asia before the Achaemenids, see now Beckwith 2023, 54–80, whose suggestions are worth of careful consideration and, if necessary, detailed – critical – discussion.Far from sanctioning a process of conquest now brought to an end, the foundation of Kyropolis is far more likely to reflect, in Richardson’s terminology, a “presumptive” affirmation of established power.41Cf.Richardson 2012; 2016 for the concept of a “presumptive state.” In the words of Sean Manning(2021, 220), “outside of the inscriptions, Darius and his servants had to deal with willful individuals who wanted something in exchange for cooperation, and with the endless intermediaries between them and the humble workers who enacted their orders.” Such a picture tailors very well with the situation Kyros and his lieutenants must have been confronted with in Central Asia during the first expansive phase of the Teispid Empire, on which see Waters 2023.

Fourth, the description of the Achaemenid settlement in terms of a bulwark of Persian power in Central Asia presupposes a highly stereotypical conception of the relations between the Empire and the peoples of the steppes (in other words,it, too, is the product of a discourse that runs through ancient, notablynotonly classical, historiography) and therefore needs to be critically evaluated.42See Nečaeva 2018 and especially the contributions by Nicola Di Cosmo (e.g., 2010 and 2018) on the invention of the barbarian in ancient historiography between Greece and China.

In other words, it is undoubtedly true, as has been argued particularly convincingly in recent years by Mischa Meier and Rollinger, that the mere existence of a geopolitical entity such as an empire is a determining factor in reconfiguring the socio-economic arrangements of entire communities oneither sideof the empire’s effective range of political and administrative control.43Cf.Meier 2020 and Rollinger 2023.It is equally true, however, that opportunities of no lesser magnitude (for instance,in terms of resources that can be acquired in order to satisfy the growing needs of the imperial apparatus) are open to the ruling class of the empire being constituted – and to the local élites that are drawn into its orbit – precisely in those frontier spaces that in Strabo’s narrative (or Herodotos’, as his narrative of Kyros’ expedition shows) emerge as an almost exclusive source of threat to the stability of the (allegedly accomplished) conquest.44Hornborg 2021 for a comparative study of the processes of what he calls imperial metabolism and the central importance of the acquisition of resources within and beyond the frontiers of a given empire, according to a dynamic that the scholar defines in terms of an “unequal exchange” (Hornborg 2021) but from which, it is essential to point out, not only the members of the imperial élite had something to gain.

Against this background, an analysis of Strabo’s passage dedicated to Kyropolis that addresses the Central Asian context in which the episode described by the geographer took place cannot fail to ask the following question.What interests – apart from those conditioned by a security-policy which seems more fitting of modern nation states than of (ancient) empires – could an undertaking such as the foundation of a settlement “at world’s end” satisfy from the point of view of the Achaemenid ruling class (both at the imperial and, above all, at the local level)?

Such a question demands a radical change of perspective.It forces us in fact to reflect on the history of Kyropolis from the point of view of those frontier zones which, in the long history of Eurasia, before and far more than a source of danger, has been an inexhaustible reservoir of resources, and in some cases even a sanctuary in which to seek refuge from the rapacious hand of imperial officials.45Beckwith 2009; Scott 2017, 219–256.

For this purpose, however, it is necessary to read Straboagainst the grainof both space and time, framing it in thelongue duréeof Central Asian history, as the next section seeks to show.46Hämäläinen 2008, 1–17 and Scott 2017, 1–35 for a discussion of the methodology of “upstream”(Hämäläinen 2008, 13) reading of the available sources in order to acquire information hidden between the lines of what the (especially written) evidence explicitly says.

4.Smugglingstān.Towards a local history of universal empires

In a passage from theTāriḫ-i Buxārā(تاریخ بخارا), composed between the 9th and 10th centuries AD by the historian and scholar Muḥammad Abū Bakr Ǧa‘far Ibn Naršaḫi (نرشخی بن جعفر بكر محمد أبو, AD 899–959), the reader suddenly comes across a curious anecdote about the city of Ṭawāwīs (طواویس),on the northern outskirts of the oasis along a vital route that connected Buxārā with Samarqand, about “seven parasangas” from the center of the oasis itself(and therefore directly facing the Chorasmian steppe), which deserves to be considered with some attention.47Tāriḫ 4.On Naršaḫi’s life and work, see, e.g., Starr 2015, 575.I take this reference and the following analysis of Naršaḫi’s account from Stark forthcoming, which provides further literature on this anecdote and a thorough archaeological background.See, moreover, Schwarz 2022 for a detailed treatment of what he calls the land behind Buxārā.

Naršaḫi tells us that in this city, as well as in other settlements, such as Kargata(کرگت), built further north, in order to avoid the payment of taxes imposed by the Buxārān administration, on the occasion of important fairs, during the month of Tīr (تیر), thus approximately between June 22 and July 22, no less than ten thousand people used to meet annually, coming from regions as far away as Čāč(some 1,000 kilometers to the east, where today’s Toškent is located), the valley of Farġānẹ (even further east), “and other places.” The purpose of such an event,he tells us, was to traffic in “defective or stolen goods [the word attested in the manuscripts of Naršaḫi’s work ismasrūqāt, مسروقات], without any possibility of compensation” and, what appears to have been the most important aspect of the entire process, sheltered from the city administration, thus making “the fortune of the villagers [of Ṭawāwīs], and the reason for this was certainly not agriculture.”

As Sören Stark shrewdly points out, thebāzārof Ṭawāwīs must, in fact, have constituted a genuine local attraction capable, by itself, of making the economy of the entire settlement flourish since the site is mentioned in the same terms(“a large and populous city”) by the polymath Abū al-Rayḥān Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad al-Bīrūnī (البيروني, AD 973–1048Tafhīm 10.Further details on al-Bīrūnī in Starr 2015, 269–278, which are devoted to his research on astronomical and hemerological matters.) in a work devoted to astronomy, the Kitāb al-Tafhīm (كتاب التفيم).Here the following description is to be found:

Even the magi of Sogdiana have their recurrences and festivals of a religious nature, which they callAḫam[....] and in theirbāzār[...] in which stolen goods are sold [again, the Arabic word is مسروقات], and great confusion reigns in them, nor is it possible to obtain repayment [...] and the fair of Ṭawāwīs, a large and populous city, lasts for seven days from the 15th of Mazhīḫandā, during the festival of Kišmīn [كشمين], which lasts for seven days.48Although apparently in all respects analogous to that of Naršaḫi, al-Bīrūnī’s testimony, particularly authoritative because it comes from an astronomical text (and is, thus,technical, implying its being less constrained by ideological or literary agendas), provides a revealing detail – the dating “from the 15th of Mazhīḫandā – in the light of which the anecdote of Ṭawāwīs’ “black market”acquires a much deeper significance, becoming therefore of considerable interest for the historian not least because it makes possible, as we shall see, to provide Strabo’s account of the foundation of Kyropolis with a broader and more meaningful context than the one allowed by a traditional reading of it in terms of the “adversarial relationship” with the steppe people.49Wu 2010, 549 for the concept of “adversarial relationship” between the Achaemenids and the Central Asians.

From the calendar under discussion in the passage of al-Bīrūnī, namely the Sogdian one, it can in fact be argued, as Stark does not fail to notice, that the month of Mazhīḫandā is to be placed in autumn, which seems particularly plausible by virtue of the fact that the visitors from Čāč and Farġānẹ were in all probability members of pastoral communities who took advantage of the winter migrations to sell their products, which had to be particularly coveted – and therefore sold at corresponding (high) prices – to the point that both at Ṭawāwīs and Kargata the goal was to shelter as much of the (mutual) earnings as possible from the rapacious eyes (and hands) of the Buxārān administration.

But there is more in such an apparently trivial anecdote: since a situation like the one described by Naršaḫi and al-Bīrūnī appears to be closely related to geoecological opportunities (in Tim Ingold’s words the “affordances”) provided by the local landscape, it is perhaps not specious to wonder whether dynamics comparable to those of Ṭawāwīs do not have a much more ancient history and whether, for example, places like the Baktrian and Sogdian fortified settlements(known asqal‘a) studied by Michelle Negus-Cleary in the context of Iron Age Chorasmia were not a remote antecedent of the “great and prosperous city”mentioned in theTāriḫ-i Buxārāand a touchstone for assessing the function of Kyropolis itself.50Negus-Cleary 2015, vol.I; 2017.The essays collected in Günther and Fabricius 2021 are critical for an assessment of the heuristic potential of such concept in ancient studies (especially from an archaeological standpoint, which is the focus of the volume).

Such a suggestion would provide a rather convincing explanation to the attention, archaeologically detectable, for example, in the oasis of Baktra,devoted by the Achaemenids to the expansion of their own sphere of territorial control – in the form of garrisons, post stations or, not least, by means of concessions and privileges to some members of the local élites, in border and impervious territories.If the Buxārān parallel has any heuristic value, the main goal of such a move would, accordingly,nothave been (as, for example, Strabo’s passage on Kyropolis implies) to circumscribe and protect the imperial space from external “barbarism,” but – on the contrary – totap intowhat James Scott has called “non-state zones,” and this chiefly, if not exclusively, because of the resources that only these (allegedly) no man’s lands (which in fact means little more than not – yet – incorporated within the imperial body) were able to provide.51Scott 1998, 419, n.55; 2009, 23–25; 2017, 155.Chinese ethnography even developed a “culinary”classification for these territories (and the people living therein).Accordingly, a space such as that in which Kyropolis was built would have been defined “raw” (shēng 生).On this curious way of classifying both spaces and people by the Chinese (late) Medieval government, cf.Fiskesjö 1999.

What kind of resources, however, must we more concretely imagine were the subject of those exchanges that, according to the argument proposed here, might have taken place at the outskirts of what Thomas J.Barfield has recently called the “archipelago” of Achaemenid political control?52Barfield 2020.In order to put forward some possible answers, we must come back to Naršaḫi and the fair of Ṭawāwīs.

To begin with, it must be noted that the mention of “stolen goods” (مسروقات)has created more than one headache for scholars since the hypothesis that these were the fruits of raids carried out elsewhere fits particularly poorly with the mention of visitors coming from places hundreds of kilometers away for a purpose that could undoubtedly be satisfied within a much more limited radius.Things, however, change radically if one accepts, as Stark does, an elegant proposal – and for this reason all the more convincing since it does little to no harm to the text – for amendment that argues in favour of a corruption,paleographically far from improbable, from ق to ف, thus suggesting a much more plausible reading for the text of theTāriḫ, namelymasrūfāt(مسروفات), or“articles eaten by woodworms (?).”53For this, indeed extremely elegant (and therefore suggestive and alluring in its simplicity)hypothesis, see the discussion in Smirnova 1970, 122–154, already referenced and discussed in Stark forthcoming.Cf., moreover, now Stark 2021 and Jacobs and Gufler 2021 with further bibliography on the Īrānian East and the steppe pastoralists under Achaemenid rule.

Admittedly, not even such a (indeed brilliant) conjecture solves all the problems, and in fact the possibility of seeing silk behind such مسروفات articles runs the risk of re-proposing once again the long-lasting stereotype of the nomadic middleman, committed to shuttling between East and West through the Central Asian oases, bringing with him caravans packed with luxury goods.54Such is, more or less, the picture drawn by Benjamin 2007 and 2018 concerning the Yuèzhī, the Arsakids, and the Kuṣāṇa.On the two latter case studies, see the theoretically much more refined assessment of Leonardo Gregoratti (2017 and 2019 on the Arsakids) and the critical remarks by Lauren Morris (2019b, 681–688, concerning what she rightly labels a sort of crystallization into doctrine of the myth – for such it is – of the Kuṣāṇa middleman).It is, however, worth pointing out that, at least as far as the Achaemenid Empire is concerned, the hypothesis of trade(and not – only – gift giving or tribute) in precious textiles between the Central Asian satrapies,particularly Baktria, on the one hand and the steppe world on the other should not be dismissed out of hand, as a passage in the Συλλoγὴ τῆς περὶ ζῲν ἱστoρίας strongly suggests: see FGrHist 688 F 45 (26)and the conclusions reached by both Henkelman and Folmer 2016, 195 and King 2021, 359–361.

As William Honeychurch has recently pointed out corroborating his assertions with plenty of both archaeological evidence and insightful ethnographic parallels,it seems on the contrary much more feasible that, in the case of Ṭawāwīs at the very least, we are dealing with goods, whatever it is to be understood behind the cryptic مسروقات/مسروفات, coming from a network of relations (a “political community” in Honeychurch’s words) accessible to the population settledat and aroundṬawāwīs (as well as, at least in its intentions, to the Buxārān administration)exclusivelythrough the intermediation of the peoples of the steppe, consequently overturning the persistent and, as it seems, heavily biased,imago receptaof a structural dependence of the nomadicum onThe Outside Word.

In fact, what the anecdote preserved by Naršaḫi shows, is the exact opposite,namely, how it was the latter (we might even say: the Empire) who was tenacious-ly looking for goods coming from circuits of exchange and mobility laying beyond the community of Ṭawāwīs (and of Buxārā itself, meaningoutsideof the reach of imperial administrators were it not for the cooperation, which would of course have come at a cost, of local magnates).55Honeychurch 2015, 86–99.Cf.with regards to the (questionable) argument of structural dependance of the steppe economy from other (agricultural) networks Khazanov 21994, 68–84 and(more recently, using the Huns as a case study) Meier 2020, 406–470 on the one hand and, on the other, Beckwith 2009, 320–362 and Scott 2017, 116–150.

In the light of such an interpretative framework, the inescapable question to ask next is: on what resources from the steppe world (and more generally from relational networks of wide-ranging mobility) could the Achaemenid Empire in Central Asia have been so dependent – and consequently desiring them with the same ardor as the Ṭawāwīs inhabitants (and the local administrators in Buxārā)?The most plausible answer is likely to include at least three categories of “goods:”horses, camels, and, finally, the labor necessary to adequately take care of the first two.56Taking up a remark in Horden and Purcell 2000, 100, we might argue that Ṭawāwīs, and especially its bāzār, seems to have been a locus “of contact or overlap between diferente ecologies.”

Indeed, if it is true, as Christopher J.Tuplin observed in an exhaustive study some years ago, that from amilitarypoint of view there is no reason to assume a particularly prestigious role reserved for cavalry – and horsemen – within the Persian army, it is nevertheless equally true that, especially in the second phase of the Achaemenid imperial trajectory (roughly from the second half of the 5th century to the death of Darius III in 330 BC), the use of highly mobile units (on horseback and camel), made up especially bynon-Persians (in the sense of composed of peoples not originating from Fārs, namely, the so-called barbarian cavalry known to classical historiographers) seems to have been very widespread.57Tuplin 2010.

Moreover (and perhaps far more importantly), it should be noted that, with the exception of Media, repeatedly mentioned as an almost inexhaustible source of horses, and especially of the – apparently exceptionally valuable – Nisean specimens (Nησαῖoι καλεόμενoι ἵππoι, according to Herodotos), the sources of supply available to the Achaemenid kings donotseem to have been many and,for the present discussion a remarkable point, they appear to have been mostly located in areas notoriously difficult to control, from the Negev desert (נגב, i.e.,“south [of Israel]”) to the Armenian Plateau up to the Sogdian steppes and the Farġānẹ valley, whose semi-legendary “celestial horses” (in Chinese known as dàyuānmǎ 大宛馬) still in the 2nd century BC populated the fantasies of the“Martial Emperor” Hàn Wǔdì (漢武帝), who in fact considered their acquisition indispensable for his (massive) campaign against the Хiōngnú.58The importance of “barbarian” cavalry is explicitly formulated in Nep.Dat.8 and Diod.Sic.14.99.2 (see, most recently, Manning 2021, 183–187).About Media as a satrapy ἱππoβότης par excellence, see at least Hdt.3.106, Polyb.5.44, Strab.11.13.7, and FGrHist 156 F 17 (8).That both Bactria and Sogdiana were a valuable source of mounts even in the Hellenistic period has been most recently underlined by Lauren Morris (2019a, 382–383).For the Nisean horses the main source is Hdt.7.40.2: whether these horses were of Median origin or should be identified with the dàyuānmǎ from Farġānẹ mentioned by the Shǐjì (123.21) is a question that will probably remain unsolved.However, as Sven Günther kindly pointed out to me in a personal communication (11.12.2022), the entire story of emperor Wǔdì’s obsession for these mounts is particularly interesting in the context of this paper, for it shows a compelling analogy with the Achaemenid (and Assyrian) precedentes concerning the demands, the reach, and the limits thereof, of imperial authority.Other horse reserves in Armenia and Media Atropatene (modern Azərbaycan and Northwestern Īrān): see Potts 2014, 78;SAA I no.29, SAA V no.171; and Balatti 2017, 127–134.

Now: according to what we can judge from the Persepolis archives, apart from the rather interesting cases of individuals on horseback coming from Baktria and Chorasmia and recorded, perhaps in a military context, as active in Egypt, even more remarkable is the existence of ahierarchyamong the imperial officials(mudunraormudunup) in charge of the care and breeding of horses, some of which explicitly belonged to the Great King (or to what with Wouter Henkelman we might define “the royal economy:” see as a way of example PF 1668 and PF 1669).

Moreover, it seems that among the criteria behind the establishmend of such a hierarchy was thequalityof the horse breeded, as is suggested by the titles ofaššabattiš(“head of horses”) as well as, and above all,pasanabattiš, that is, the“head of the excellent filies” or, finally, by the remarkable fact that in at least four cases (PF 1793, NN 0751, NN 1289, and NN 1352) officers with this title were used to receive meat rations, which provides a compelling clue for their special social status.59On the aššabattiš and the occurrences of this office in the heartland’s record, see Tuplin 2010,132–133 for the unpublished tablets mentioned here.About Central Asian detachments (of Bactrian,Chorasmians, but also other Iranian groups) in other satrapies of the Empire (not only Egypt but also Asia Minor) see, e.g., TADAE D2.12 and TADAE D3.39 with the relevant commentary by Tuplin 2010, 155–156, as well as the mention by Arrian (Anab.4.4.4) and Polyaenus (7.8.1) of the peculiarities of the “Scythian” art of warfare (including the famous “Parthian shot,” which however does not seem to have been the prerogative of the peoples of the steppes, let alone of the Parthians alone: see Overtoom 2020, 46–56 for further details on Central Asian warfare tactics).On the royal economy of Persepolis, see, e.g., Henkelman 2005 and 2010 (the definition mentioned in the text can be found at 2010, 675).Regarding the titling that occurs in the archive: mudunra or mudunup are attested in PF 1018 and NN 2184.An aššabattiš is mentioned in PF 1978, and as for pasanabattiš at least two occurrences can be quoted: PF 1947 and PF 1972.See also Tuplin 2010, 132–135, who postulates that the title of “horsemen” in the sense of “attendants to horses” was a rank of some importance within the imperial administrative hierarchy, but points out (ibid., 133) that meat rations could be a “one-off” donation and not the normal payment of these officers.

Not only that: in one of the most important – and controversial – documents that make up what remains of the archive(s) preserved in theAramaic Documents from Ancient Bactria(dated between November and December 330 BC), line 33 of the first column of parchment C1 (a list of supplies) records the procurement of an unspecified commodity in a place called Asparāsta (’sprstin the Aramaic text, i.e., אספרסת), a toponym interpreted by the editors as indicating “(a place)for horses, a hippodrome?”60Shaked 2004, 32–33, Naveh and Shaked 2012, 174–185 C1 = Khalili A21: on such issue, see Tuplin 2010, 178–179, and Naveh and Shaked 2012, 184 for the etymological reconstruction of the hypothetical toponym אספרסת.

Should the proposed etymology be correct, even although lacking adequate context, the mention of (only one?) אספרסת in Baktria would be an extremely interesting piece of information, for at least two reasons.The first is the existence of a similar infrastructure attested in Idumea under the name ofrkšh(רכשה) which Tuplin proposed to interpret as indicating “a ranch” intended for the breeding – unfortunately, we do not know if by locals, but it would not be a hypothesis to be excluded – of horseson a large scale(a similar business to the one carried out in Gaugamela, this time, however, for camels, at least according to Plutarch).61Tuplin 2010, 120–122 on the Idumean ranch, with further references.Regarding the toponomastic of Gaugamela, cf.Plut.Vit. Alex.31.3 with Henkelman 2017, 57.Cf.the evidence coming from early medieval China discussed by Skaff2012, 258–262.In addition, it is worth remembering incidentally that horse breeding (and their trade for “imperial” buyers) has historically been a very profitable activity for groups of non-sedentary shepherds – from the O‘zbeks to the Türkmens down to the the Aimāq (ایماق) – who were able to supply the thriving Balḫ-āb oasis market along a route that reached as far as India still in modern times.62Barfield 2020, 15, with further ethnographic bibliography.

The second reason concerns the parallel, worthy of further study, that facilities such as the אספרסת of Baktria, the Idumean “ranch,” and Gaugamela itself present with the infrastructural network – of immense proportions – set up by the Táng Dynasty on the northern border of their domains, in the direction of presentday Inner Mongolia and Manchuria, and especially in the Ordos Plateau (known in Chinese asÈěrduōsī鄂爾多斯), with the dual purpose of (1) acquiring, if necessarymilitarily, the specimens bred by the Türkic and Mongolian speaking peoples, including the famous Prževal’skij mounts, considered among the best for military purposes, and (2) of procuring a sufficient number of stallions and mares – as well as the necessary workforce to maintain them – to start adomesticbreeding on a scale that the available figures, recently studied in considerable detail by Jonathan Karam Skaff, allow us to define as “industrial.”63Skaff2012, 241–270 and 2017, in both cases with previous bibliography.Between AD 590 and 837, the Táng Dynasty was able to establish a network of ranches in territories bordering with the Inner Asian frontier of China which covered some 16,000 acres, which around the early 8th century AD was made out of some 65 ranches in which several hundreds of thousands of livestock were sheltered (766,000 animals in AD 725 according to the Xīn táng shū 50.1337, among which were 43,000 horses).

Considering the war resources – in terms of “barbarian” cavalry – that both Bessos and, especially, Spitamenes seem to have been able to mobilize starting,in the case of the latter, from bases such as Koktepe, not by chance situated along theShadow Linebetween Achaemenid territory and the Scythian steppes (what might be called an ecotone), it does not seem too far-fetched to assume that the expansion of this and other sites (such as Čašma-ye Šifâ or Altin Dilyar in Afġān Baktria, Koktepe itself in Sogdiana, and, it might be argued, Kyropolis itself deep intoSakāterritory) served the primary purpose of gaining access, following theṬawāwīs model through tax collection and, if necessary – according to the Táng example – through military incursions (Darius’ Scythian expedition, for instance,and perhaps Kyros’ itself), to a portion of the “heavenly horses” for the cavalry of the King of Kings.64On Afġān Baktria, see Martinez-Sève 2020.Further bibliography on Čašma-ye Šifâ and Altin Dilyar in Ball 2019 (nos.186 and 38).

In the latter case – it must be emphasized – we are dealing with a scenario within which there was ample room for maneuver for the so-called gatekeepers,namely, individuals and/or social groups capable of guaranteeing the Achaemenid administration access to the desired resources at the lowest possible cost(including those – far from negligible – of military expeditions).Accordingly,these men and social groups came into possession –becauseof the establishment of the Empire in Central Asia and its consequential need to extractlocalresources to feed the satrapal apparatus – of a critical negotiating power.This could be put to usebothwhen coming to terms with a, undoubtedly cumbersome,presence like that of the Achaemenid Empire and with its representatives(themselves withtheir ownagendas to promote) and within the local societies inside and outside the borders of the newly established polity since the imperial need for resources and human capital is likely to have stirred competition among local élites in Central Asia, from which could only profit who was able to tap into the Achaemenid administrative and political networks.65See Rollinger and Degen 2021a, 199–203 for a wide range of comparative case studies (from Assyria to 15th century China), which strongly support the scenario laid out here.

By virtue of its strategic position in close contact with the Üstȳrt plateau, it is easy to think that Chorasmia played a significant role in this economy: the possibility of the existence of some kind of Ṭawāwīsante litteramat least in this region – in Achaemenid times under the control of the satrap of Batria – seems to be suggested by the existence, at least from the 1st century BC but likely to reflect earlier practices, of numerous sites (the Russian archaeologist Sergej Bolelov has found about eighty of them), each equipped with granaries for storing agricultural products, wine presses and even kilns.66Bolelov 2006.

In Bolelov’s opinion, the main purpose of these small agricultural settlements(the occupation of which seems to have been of semi-permanent nature) was to produce consumer goods that could be exchanged with the surrounding pastoral groups (in Tsarist times mainly Türkmen).The emergence of these sites on the fringes of the agricultural territory of the surveyed area suggests the intention of the oasis inhabitants to (literally) come as close as possible to the steppe dwellers, which in turn leads one to suppose that the interest in keeping alive this space of socio-political and economic interactions was greater on the partof the formerthan of the latter.67Crescioli 2017, 140 on the possibility that on the Empire’s frontier territories (“mainly Bactria,Sogdiana,” but in the light, for example, of Michele Minardi’s studies – e.g., 2021 – it seems only reasonable to add Chorasmia as well), “workshops (e.g., for jewellery [sic]) specialized in the production of objects for the nomads” flourished, most likely sponsored by the imperial administration itself, in the attempt of tapping into the steppe’s sociopolitical network, which Minardi 2020, 18, n.26 with references has convincingly shown that, starting from Chorasmia, were able to reach as far as the Ural mountain range.Otherwise stated, the Empire needed its “enemies” at least as much as they needed it, if notmore.68This is the overarching argument of Beckwith 2009, looking at the so-called Silk-Road from the perspective of the Eurasian steppes.

Finally, the discovery of a small fortress at the site of Baštepe – once again located along an ecological and sociopolitical borderland, at the outskirt of an oasis facing the mighty Kyzylkum desert – represents an important clue supporting the hypothesis that thelimesof the Central Asian steppe was an area of interest for several social actors, some of which, for example, the Achaemenid Empire, must have spared no resources in their attempt to become part of exchange circuits such as those revealed by the survey carried out by Bolelov and by the anecdote told by Naršaḫi, in Chorasmia and probably much beyond over the territory of Achaemenid ruled (or claimed) Central Asia, including, as this paper has argued,Sakāinhabited land along (and beyond) the shores of the Syrdaryo.69Cf.Stark 2012, 111; 2017; 2020 (on Central Asia and its relationships with the steppes); 2021.See,moreover, Jacobs and Gufler 2021 on the Achaemenids and the Sakā.Recently, the Uzbek-American Expedition to Bukhara directed by Sören Stark himself and Fiona Kidd (New York University) has discovered – August 2021 – a diagnostic fragment of Achaemenid pottery coming from Baštëpe(formerly thought to have been founded ex nihilo during the Seleucid period).Against the background of the previous pages, the hypothesis that the Persian administration in Bactria (through Chorasmia?)had interests in the Buxārān steppes comes as little to no surprise, especially if one thinks that it is exactly from this area that Spitamenes was able to draw much of his cavalrymen as he was fighting against Alexander.This was known to Strabo himself, for he reports that the Sogdian notable was able to take shelter “among the Chorasmians” (Strab.11.11.8).

4.1.Kyropolis strikes back: Strabo at world’s end

In the light of the discussion carried out so far, let us come back to “Kyros’furthermost foundation [κτίσμα] on the banks of the Iaxartes,” the “bulwark[ὅριoν] of the Persian domain (τῆς ἀρχῆς),” and try to rethink the context – and the purpose – of its foundation against the background of the evidence presented in the previous pages.

Although nothing certain is known about the pre-Achaemenid Хuçand, the examples of Ṭawāwīs and, above all, of Baštepe, allow us to assume a similar function for Kyropolis, namely, that of an imperial bridgehead towards the steppe world with aproactiverather thandefensivepurpose: for example, with the intention ofcontrolling(and exploiting), rather than impeding, wide-ranging movements such as those of caravans or, more simply, transhumance routes.70Weaverdyck et al.2021, 313–317 for precisely this argument exploiting evidence coming from Central Asia between the Hellenistic and the Tīmūrid period; King 2021, 353–361 on Achaemenid Baktria.

Likely, levies or other taxes were imposed on those caravans (and/or the mobile shepherds roaming in the area), presenting them as the price for a service of protection fromotherinhabitants of that territory, naturally reserving the possibility of moving on to openly hostile actions should one or more of such,it must be stressed,numerousinterlocutors – one might just think of the fate occurred to Skunkha, which accordingly to Darius himself was replaced byanother(more collaborative?) chief – had shown little inclination to dialogue.71Ibid., 347–361 convincingly developed this very same argument based on a careful study of the ADAB parchments (in particular of ADAB A1).There is in my view no reason to assume that two centuries earlier this was not already established common practice, not only by the Empire and its representatives, but by the Sakā as well: see Beckwith 2023, 48.Such a scenario, it is worth emphasizing, fits remarkably well with wider Eurasian patterns such as those scrutinized by Nicola Di Cosmo within the context of the relations between the Hàn Empire and the so-calledPerilous(for the “nomads” at least as much as for China)Frontierin the northeast, especially in the Ordos and Inner Mongolia.72This is precisely the strategy that, according to Clavijo (Embassy to Tamerlane 11), had made “the lord Tīmūr the sole master of the Iron Gates, and the revenue for his state, which is considerable,comes from the taxes that all merchants heading from India to the city of Samarqand and beyond are forced to pay.” On taxing movement in Achaemenid Bactria, see King 202, 347–361.Against the model developed by Barfield 1989 and 2001, see the convincing argumentation of Di Cosmo 1999 and esp.id.2002, 44–92.Such a scenario is not in contradiction with the hypothesis that sites such as Kyropolis and the “seven cities” in its surroundings acted as Achaemenid garrisons, as suggested among others by Tuplin 1987, 181 and, most recently, by Canepa 2020, who argues that the Empire adopted a subtle (soft) infrastructural imprint for its project of settlement expansion(ism) in Bactria.

Even assuming – while by no means granting – that Kyropolis did indeed perform a presidiary function, the case studies discussed by Richard Payne(focused on Sāsānid Ērān), Richardson (ancient Babylonian kingdoms), and Scott (Southeast Asia in alongue duréeperspective) provide enough comparative evidence to suggest that themainpurpose of such – hypothetical – stronghold(ὅριoν) was not at all to keep the “barbarians”out, but rather to extract reosurces(and taxes) from those people if not even to prevent, as much as possible, those who lived, by love or by force, within the imperial borders from trying toescape,attracted as they might have been, especially in the case of the less privileged social strata, by the conditions of life in thenomadicum, which, as argued by Christopher Beckwith and Scott, were indeed probably much better than those availablewithinthe Achaemenid “civilization.”73See, most recently, Scott 2017, 219–256.A similar issue is discussed in Hämäläinen 2008, 257 –258.That the only aim of Kyropolis was to protect the Empire’s borders against the Sakā is still a shared opinion among scholars: see, e.g., Matarese 2021, 52.

Otherwise stated, it could be argued that, to use Payne’s words, in the case of Kyropolis we might be confronted with another strategy of “territorialization”put in place for purposes of socio-demographic control and in the absence of which the effective administration (and relative exploitation) of a given space would have proved nearly if not outright impossible.74Cf., respectively, Richardson 2012; Payne 2015; 2017; Scott 2009, 23–25; 2017, 155–162.

Beyond horses, a second category of steppe “goods” which, given their paramount importance, might have justified the effort of building a site such as Kyropolis, is represented by camels.75See now King forthcoming with full bibliography on the camels of the King between Persepolis and Bactria.As an example of the strategic use of these animals, beyond the testimony provided by the Persepolis archive, it is not out of place to mention Herodotos’ account of the Achaemenid conquest of Lydia, according to which the excellent local cavalry, among the best in Asia,was defeated thanks to the use of camel-mounted troops, the origin of which we can only speculate on, but which it would not be implausible to locate in Central Asia, all the more so if the conquest of Sardis were to be placedafterat leastoneof Kyros’, apparently numerous, expeditions to the upper satrapies.76Cf.Hdt.1.79–80.Aristot.Hist. An.2.1.10–15 focuses on the physical description of the animal,explicitly teasing out its main differences with its “Arabic” counterpart (namely the dromedary).

It is, however, the third of the above-mentioned “goods” that needs to be studied in some further depth, and this because of the research prospects it could open up with regard both to Achaemenid society, especially at its frontier territories, and to the possibilities of social ascent available to – local – bearers of what Scott has calledmēticskills.77Scott 1998, 309–341, meaning social and ecological skills enabling individuals or groups to take advantage of the local environment in ways precluded to foreigners.

Horses as well as camels, even once preyed upon in “barbarian” territory,require in fact skillful and meticulous care, the acquisition of which technical prerequisites constitutes a far from trivial matter.It is probably for this reason that, in Táng China, as much (if not more, which is already saying quite a lot)coveted than the Prževal’skij horses was the labour force (cf.the “head of horse” attested in the Persepolitan archives) able to guarantee (1) the welfare,(2) reproduction rates, and (3) optimal yield of the herds, to the point that a prisoner of war from the steppes could cost – on the Chinese slave market – up to three times as much as a not equally qualified equivalent (and this despite the ubiquitous derogatory descriptions of the steppe world to be found in historical texts – for example, in the work of the historian and statesman Bān Gù 班固).78Skaff 2012, 295; 2017, 48; and see most insightfully Chin 2014, 143–188 with further textual references and bibliography on Chinese ethnography and historiography on trade and exchange with non-Hàn people (including, but not limited to, the Hànshū 漢書).For what might have been a Babylonian equivalent during the “long 6th century,” see Manning 2021, 184–185 on the šušānu,most likely “herders and gardeners from areas of steppe and semidesert whom ambitious kings tried to force to settle down.” It could be argued that a similar institution was adopted (and adapted) by the Achaemenids in Central Asia, not least thanks to the expertise of local – including Sakā – people.

The available sources (e.g., the invaluableXīn táng shū新唐書,New Táng Annals) testify to the origin of this particularly prized category of labor force within ethnic minorities (especially Sogdians), and from some biographies of these men we are able to guess what career opportunities within the imperial administration the possession of skills in this specific branch of veterinary medicine was able to ensure.79Sogdian was almost certainly a certain Mǐ Zhēntuό (米真陀), another official appointed to cavalry duties (therefore, in Tuplin’s terminology, a Chinese “horse master” of sort; Tuplin 2010, 132–135):cf.Skaff2012, 263–264.

Wáng Màozhōng (王茂中), for example, a native of the Korean peninsula(Koguryŏ고구려), even became head of the imperial stables together with Zhāng Wànsuì (张万岁), who was also a provincial, for he was in fact a native of the city of Mǎyì (馬邑), or “city of horses,” in what is now Shānxī province (山西).As for Lǐ Lìngwèn (李令問), he was elected vice-minister in AD 713 and for years held crucial diplomatic appointments (including state murder, therefore a sort of assassin) in particularly sensitive areas along the western frontier of the Táng Empire by virtue, it should be noted, of his very close contacts with the steppe world, which he acquired through marriage with the Uyġur élites then settled in today’s Gānsù.80Xīn táng shū 133.4547–4548, Skaff2012, 209 and 2017, 51, with further bibliography as well as other textual references.

The most interesting story, however, is perhaps that of a certain Mù Bōsī(目波斯) whose name, literally, means “Persia,” a fact that makes his Central Asian origin – once again most likely Sogdian – extremely probable.Sometime around AD 750, this individual was in fact taken from the same Gānsù (then called Héxī) in which a few decades earlier Lǐ Lìngwèn had been active from the imperial court by virtue of his fame as a veterinarian and transferred with all honors to China.81Skaff 2017, 52: think, on the one hand, of the Krotonian Demokedes (Δημoκήδης), “the most skilled physician of his time” according to Hdt.3.129.3, who served and was highly regarded at the court of Darius to such an extent that, in Herodotos’ account, he had to resort to subterfuge in order to leave the gilded prison at Susa in which the Achaemenid ruler intended to keep him, and,on the other hand, to the observations of Kauṭilīya (कौटिल्य) in the Arthaśāstra (अर्थशास्त्र: e.g.,2.32.15–16: Dwivedi 2021, 238–240) about elephant breeding (on which see also Trautmann 2009 and 2015): even after capture – in itself a complex and risky job, which therefore also required skilled labor – and training, the maintenance of a pachyderm required the employment of no less than 14 people, including veterinarians, tamers, stockers (see Hack 2011 on the exorbitant daily consumption of a single animal), and so on.

Unfortunately, the documentation currently available does not allow to draw up a prosopography even remotely comparable to that of Táng China for the Achaemenid period.However, the comparative material explored in these pages allows to consider in a significantly new light the – precious little – information on individuals such as Spitamenes or Arimazes as well as the more detailed,but mostly context-free, evidence coming from theAramaic Documents.82Evidence such as PF 1943 shows that “Master of the Horses” served at the Persian court and were highly prized for their services: it would not be surprisingly if at least some of them came, not differently than Mù Bōsī, from regions of the Empire, such as Media, Armenia, or Kilikia (but also from Sogdiana, Chorasmia, Baktria, and even the lands of the Sakā) where horse breeding was part and parcel of the local way of life and economy (cf.Diod.Sic.17.110, Strab.11.13.7–8, as well as Hdt.3.90).Further on the Chinese comparandum, see Cunliffe 2015, 248.Most importantly for the purpose of the present paper, the evidence discussed so far allows to set Strabo’s passage on Kyropolis against a wider (Central) Asian background, with important implications for the dynamics characteristic of the imperial borderlands at its northeastern fringes.

At a more general level of methodological order, the discussion developed so far should have revealed the need to consider a space such as Achaemenid Central Asia in the framework of a system of multiform relations (insofar as it was functional to the different interests of numerous actors, often in competition with each other and with imperial officials) centered on the world of the steppes and in symbiotic relation with the socio-political circuits of those worlds.83Arguments similar to those discussed in this section have also been recently put forward by Rhyne King (2020) in light of the evidence coming from an important documentary corpus originating from the district of Rōb (some 80 kilometers south of Samangān, سمنګان in Afġānistān) in the context of a study dedicated to the relations between aristocrats, subjects and imperial regimes, see, moreover,Payne and King 2020.King’s words (2021, 26–27) are worth quoting at some length: “Imperial administrators moved laborers from Arachosia to the imperial core because labor, in particular skilled labor, was the resource the Empire desired most.” The steppes, as this paper seeks to demonstrate,provided access to this very needful thing as well as to a wide range of natural resources, especially horses and camels.

Therefore, the aim of the remaining pages of this paper is, on the one hand,to delve further into the dynamics underlying this relationship(s) and, on the other, to show how it simultaneously provided the means for the imperial administration to seize the necessary tools to control their functioning, and to the actors involved in this (in principle unequal) dialectical exchange, the means to negotiate their social position (and their political and economic space for maneuver) both within their own community and within the new institutions built – but notentirelycontrolled – by the new masters of Central Asia.

Put it otherwise, according to such an interpretative framework, what we were witnessing here would therefore be a dynamic ofparticipationrather than (sole)coercion, as recently argued by Rhyne King in the context of (late antique)Baktria.84King 2020, 263–264.It is against such a background that we should read Strabo’s account of Kyropolis’ foundation.

5.Taming the wild field.Living in and claiming the space

For the purposes of the present essay, the most important consequence of the issues discussed above is the need to rethink the process of the formation of the Achaemenid satrapy of Baktria – and of its steppe borderlands – from a perspective that, on the one hand, takes into serious consideration the physical geography and – more generally – the ecological features (which also means including aspects of what today we would callhumangeography) of this portion of Central Asia.

Otherwise stated, we need considering them to all intents and purposes associal actors, different from each other but operating in a synergistic manner,and as able (moreover) to condition human behavior through both thevariousopportunities (Ingold’s affordances) they offer, while at the same time not losing sight of the limits imposed by them to the plans and goals of empires and their representatives, and this because of the latterlacking, or not possessingenough,the skills necessary to take advantage of those affordances.85See the seminal Ingold 1992 for discussion of this topic.

On the other hand, the critical approach that this paper sought to adopt emphasizes that the multiple landscapes that emerge as a result of the humanenvironment interactions and entanglements such as those highlighted by the account of theTāriḫ-i Buxārāare neither static nor constant, but arecontinually(re-)producedon the basis of the relationships between a wide range of subjects,each endowed with its own proactive capacity (agency), from individuals, to broader communities, to empires, over the course of time.86Similar conclusions (especially as far as the non-deterministic nature of the processes described in this paper) have been reached by Barfield 2020.

It is only from this premise, therefore, that it is possible to think constructively about how supra-regional entities (endowed, consequently, with supra-regionalambitions) such as empires are able – or not – to fit into these social, economic,political, and symbolic networks, as well as about the role that empires themselves have played, in the Central Asian scenario, in shaping the interactions between themselves – in the form of their representatives –, local communities,and the natural environment(s) they moved in and acted upon.87Cf., e.g., Ingold 1993, 156, who rightly points out that each landscape should be understood as the world as it is known from those who inhabit it, who dwell in the different places of which this same space is made out and who moves through its different parts.The ever-changing nature of the spatial context in which a given empire and its representatives on the ground aims at tapping into might therefore be understood as one of the reasons which help to explain the in statu nascendi condition of Achaemenid imperial power in Central Asia at the time in which Kyropolis was built.

The hermeneutic potential of this theoretical toolkit for the study of the Baktrian context (especially, butnotexclusively during the building phase of the Achaemenid Empire) is tremendous, not least by virtue of the fact that it allows us to understanddialecticallyboth the characteristic features of the process of imperial transformation of Baktria (in the words of Henkelman, the Persian “imperial signature”) into an “imperial space” and the unavoidable role playedwithin this same processby social actors who, for different reasons, the documentation – both archaeological and,a fortiori, epigraphic or literary – doesnotallow us to clearly distinguish (or consciously tends to obscure).88Henkelman 2017 on the Achaemenid imperial paradigm and its concrete application on the ground(the signature).

That such actors not only existed, but also contributed decisively to the successes of the Achaemenid Empire (celebrated, for example, in the Apadāna,in the founding charter of Susa or proven by the sheer fact that Kyropolis lasted until it was razed by Alexander) can be deduced from the very needs – for example in terms of natural resources or labor – of a polity as complex as the Persian Empire was, which must have generated in various regions of the territories “far away from Persia,” where “the spear of Persian man has delivered battle,” as Darius has it in his Naqš -i Rustam inscription, real economic and social “micro-systems” born out (and thereforeconditionedby while at the same timeconditioningthem) what Düring and Stek calls the (local) practical situations on the ground.89Cf.DNa § 4 for Darius’ “cosmological blusters” (Scott 2009, 34, trans.Kuhrt 2007, 503).Düring and Stek 2018a, 10 for the “practical situations on the ground,” and Hornborg 2021 for the ecological“unequal exchange” which political entity such as the Achaemenid Empire set in motion while at the same time depending on their smooth functioning.