An Embodied View of Physical Signs in News Cartoons

2018-01-25XiaopingWang

Xiaoping Wang

Soochow University, China

1. Introduction

The centric position of the “body” in the field of embodied cognition is exhibited in two dimensions: one being that the generation of experiential gestalts for metaphorical processing is largely dependent on the sensory-motor system; the other is that different body parts and their corresponding functions are also active sources for embodied experience. They are found to play their roles as basic reference points for the embodied cognition of humans. After being used repeatedly in daily communication, these body parts or actions are gradually refined and schematized as conceptual structures. Typical instantiations of these structures are not quite uncommon in our daily context and there seems to be no difficulty in looking for conceptual projections based on body structures or organs, like “the foot of the mountain”, “the footnote”, “the foot of the bed”, etc.These metaphorical expressions illustrate how the “foot”, previously as a body part, now functions as a substitution in different situations. More accurately speaking, it has already become a sign, referring to various cognitive targets in different contexts. Illustrated by the above instances, we see how concepts or things gradually lose their original reference and transform into pure semiotic codes, whose meaning are co-determined by grammatical structures and context of use.

It ought to be noted that the body has been exposed to the physical world around it with the various senses as sources of information, and therefore those signs, which are actually the condensation or abstraction of bodily experiences or feelings (Zhang, 2014),can be referred to as physical signs. The interpretation of physical signs is exposed to two major problems: for those in verbal or written discourses, new signs seem still quite dependent on the linguistic description of another image, and consequently, the interpretation of one sign is usually achieved by referring to another sign (Zhao, 2016,p. 102), without penetrating into the root of the signs’ generation; for those signs in nonverbal discourse, researchers from different disciplines such as philosophy (Lakoff &Johnson, 1999), psychology (Yin et al., 2013), linguistics (Sun, 2010), and semiotics(Violi, 2008), have conducted some research. However, most of it remains focused on the level of perception, or more specifically, on the level of feeling, memory, and image in terms of the very root of semiotics. Very few of them trace the semiotic nature and sources of semiotics to the level of the body. This research, therefore, turns to the view of embodied cognition to explore the above issue, striving to delineate the link between embodied cognition and semiotization.

Embodied cognition, by nature, underlines the centric position of bodily experience in cognition (Long, 2016). Therefore, it is critical to decipher the cognitive process of the body and its function, particularly in metaphor studies, the answer of which has reached a consensus that metaphorical representation or mapping is reliable in bodily sensory-motor experience. Despite the consensus that there are at least two weak points in this field, discovered when the relevant studies of the function of the “body” are scrutinized: 1) many studies have primarily worked on a specific single dimension of the body, lacking a dynamic and comprehensive perspective, viz. body structures or organs, regarded as basic reference points in cognition, are found to exert restrictive effects on cognitive process of metaphor (Sun, 2010, 2015, 2016); some others, on the other hand, highlight the constitutive functions of different perceptual experience, such as temperature, or tactile or spatial senses in the directive roles of representing abstract metaphorical concepts (Yin et al., 2016). In factuality, be it restrictive or constitutive,the functions or effects of the body respectively correspond to one specific aspect of the embodied cognitive process. Put simply, the function of the body in cognition should be scrutinized dynamically, in different stages or various dimensions, rather than in a static manner, of the process of metaphorical representation. 2) Since embodied cognition is multimodal in nature (Barsalou, 2010), or more accurately, the similarity of objects and its representation might turn to perceptual simulation of various senses, non-verbal modes (which are, naturally, similar to language) are also semiotic and motivated. The embodied process of metaphors in multimodal forms cannot be ignored, particularly in terms of the link between perception and embodied representation (Connell & Lynott,2011; Zhou & Christianson, 2016; Luo, 2016). These are what should be taken into account when exploring the semiotization process of physical signs from the perspective of embodied cognition.

It has to be noted that it is through its vehicle that a sign is perceptible, and the perceptible part of a sign is, according to Saussure, named the “signifier”, or, according to Hjelmslev, the “plane of expression”. In terms of the representation of metaphor, it is also comprised of different planes. For instance, Tan (2016) points out two different layers, namely, the linguistic representational level and the conceptual level. In fact, the embodied schema on the conceptual level can be realized on the linguistic level on the condition that it must be based on embodied experience in a specific context. To put it differently, the two layers of form and cognition are in need of a specific cognitive context as the link, which signifies that the process of metaphorical representation can be divided into the linguistic, cognitive, and contextual levels respectively, and for multimodal metaphors, the linguistic level can be replaced by the formal layer.Corresponding to the three different layers of metaphor representation, this research will target the manifestation and its semiotization of physical signs in news cartoons.Specifically, it strives to answer the following three questions: first, what are the roles played by perceptual senses in the generation of physical signs in news cartoons?Second, how can physical signs in multimodal forms realize their encoding process?And third, amid the process of modularization, how can the meaning of physical signs be realized?

2. Perceptual Senses and Forms of Physical Signs in News Cartoons

The theory of embodied cognition argues that the perceptual experience acquired by cognitive subjects is linked to the conceptual system through sensory channels. It is based on these channels that gestalts or schemas of certain things arise. As to the fact that the essence of metaphor is understanding relatively abstract or strange experience or concepts by virtue of relatively concrete experience or concepts, many notions, from an embodied perspective, are based on sensory perceptions. For example, “viewpoint” as an abstract concept, could be considered to be “obscure” or “clear” and a difficult situation might be compared to “standing on hot bricks”. That the above metaphorical expressions can be accepted or understood in the English speaking community might be attributable to their shared neuro-physiological foundation for concept representation and for bodily experience. Certain bodily experience is activated amid the cognitive processing of certain concepts (Han & Ye, 2014, p. 921). To put it differently, in the process of conceptualization of certain linguistic expressions, situation as well as certain cognitive states can all be simulated by perceptual senses, and the understanding of certain concepts can therefore be regarded as a type of embodied process, or more accurately speaking, the reactivation of sensory-motor experience.

It has to be noted, however, that the construction of specific concepts in the cognitive process is based on multi-sensory channels. It is naturally concerned with issues like the representation of the visual or auditory resemblance of specific entities (Solomon &Barsalou, 2004). For instance, when in front of a rose, one might be exposed to various sensory stimuli like the form of a flower (visual channel), its colour (visual channel),scent (olfactory channel), spines (tactile channel), etc., and these traits of the flower,which correspond to different bodily senses, constitute the multi-sensory representation of the concept “rose”. Therefore, amid the process of identification, categorization, and cognition of two different concepts in an analogical manner, people need to reactivate multi-sensory experiences that were previously used in order to achieve the conceptual construction.

2.1 Mode and multimodal metaphor

In the concept of multimodal context, mode is defined as “a sign system interpretable because of a specific perception process” (Forceville, 2009, p. 22), which can be further divided into nine different sub-classifications, including written language, verbal language, static pictorial mode, dynamic pictorial mode, non-verbal sound, gesture, etc.This definition, in the field of semiotics, might be quite easily mistaken with another two concepts that are of great relevance, namely, medium and channel. Specifically speaking,the concept of mode in multimodality studies is more or less equal to the semiotic vehicle in semiotics, or more accurately, the signifier or plane of expression; whilst the medium is comparable to the transmitter, enabling the perceptible part to be transmitted;channel, on the other hand, refers to the path that the sensory information takes to arrive at the receivers, which should be classified according to the sensory organs, and include the visual, olfactory, auditory, gustatory, and tactile senses. Take cartoons from magazines for instance: the perceptible form, namely, the pictorial cartoon, is the mode,the newspaper is the media, and both of them are dependent on the visual channel. The distinction among the three above mentioned notions has to be strictly delineated in research of this field.

Based on the definition of mode, the term “mono-modal metaphor” refers to those whose sources and targets are represented in the same mode; multimodal metaphors, on the other hand, are defined as metaphors whose source and target domains are manifested by different modes or, more broadly speaking, by more than one mode (Forceville, 2009,p. 24). Lakoff and Johnson’s conceptual metaphor theory, in a way, verifies the cognitive nature and prevalence of metaphor in the conceptual system, but most evidence revealed has been largely confined to linguistic or verbal discourses, the pictorial mode, sound or gesture, etc., which are also supposed to be bricks for the representation of metaphor,and have all been under-estimated in metaphor and semiotic studies. Reversely speaking,if any discovery or revelation of the non-verbal manifestation of embodied cognition contradicts with what has been found in linguistic discourses, conceptual metaphor theory and even embodied philosophy will be faced with tremendous challenges.

In view of the modes used for representation, multimodal metaphors can be further classified into static multimodal metaphors and dynamic multimodal metaphors. The former are mainly constructed by static visual semiotics, like pictorial mode, colour,layout, or words. Prevalently found in print advertisements, cartoons, or posters, they mainly take advantage of layout, shape, design, etc., to create visual similarity and thus trigger a relevant embodied experience in potential readers. The latter, widely applied in TV or Internet programs and films, rely on more diversified forms of signs and their synergy in representing a metaphor, and turn to montage as well as editing and synthesizing to dynamically reproduce vivid perceptual traits or specific metaphorical scenes. This paper mainly concentrates on the static multimodal metaphors in cartoons.It should be highlighted that multimodal metaphors, as a particular manifestation of conceptual metaphors in multimodal discourses, exhibit exclusive properties of both multimodality and metaphor. On the one hand, in the process of metaphor representation,typical source domains are usually correlated directly to perceptual experiences, and metaphorical mapping is the process of mapping the concrete feelings or experiences of the source domain to the target domain that might not be fully perceptible. Therefore,sensory perception, as a matter of fact, is an essential chain in representing concepts or things (Yin et al., 2013). On the other hand, multimodal discourse, by virtue of different semiotic modes, simulates or reproduces specific concepts through perceptual simulation, because embodied philosophy holds that embodied cognition is the integration and interweaving of various senses and gestures. Still, concepts are comprised of the simulation of a series of internally represented worlds, physical states and behaviors (Niu,2016, p. 2), which parallels with the multimodal nature of embodied cognition.

2.2 Embodied simulation: Forms of representation of physical signs

All signs that bear practical meanings stem from the “body”, for the meanings given are in accordance with the relations between the signs and humans. Even if their referents come from nature, and not the human world, the signs’ values would still be judged in view of their relation to man before being encoded into the human world (Yan & Qiu, 2007).Therefore, physical signs not only refer to those that arise from the body or activities of humans, but to any signs that are determined by their links to the human world. For any type of sign, the first phase of its semiosis, according to Peirce, would be the “firstness”,which requires decoders “to face the form itself” (Zhao, 2017, p. 79). Specifically, sign has to turn to “form restoration” to realize its meaning, excluding anything irrelevant to meaning-generating activities. Amid the restoration process, all that is present in consciousness is a representation of perception, namely, “form”. Hereafter, the things faced by cognitive subjects will be degraded into perceptual forms that carry specific meanings. It has been mentioned above that the construction and representation of concepts relies to a large degree on the perceptual simulation of reality. It has to be noted,however, that this type of simulation is by no means a reproduction of reality; instead, it is quite selective and intentional.

In fact, be it monomodal or multimodal metaphors, the perceptual simulation process is prevalently existent in all metaphorical processes, and therefore it is not an exclusive designing feature of the embodied representation of multimodal metaphors. Instead,one of the keys to distinguishing conceptual metaphor from multimodal metaphor in terms of embodied cognition lies in the ways of representation in their simulation process. Conceptual metaphor, no matter how many sensory channels are involved in its conceptualization, can only represent relevant perceptual properties indirectly through verbal description. Some of the lines concerned with the “rose”, quoted fromThe Dream of the Red Chamber, are a typical case in point: “The third, Baoyu’s sister, we call her‘Rose’… Sweet and pretty and everyone loves her but she has a thorn” (Cao, 1973, p.1296). Obviously, the above description strives to simulate the perceptual features of the source domain “rose” through visual, olfactory, and tactile channels, though it is, in the end, achieved merely by linguistic expression. By doing so, though it can describe,to a certain degree, the different sensory feelings, by no means can it fully reproduce or reactivate the perceptual properties of non-verbal modes or modalities. Comparatively, in multimodal discourses, sensory perceptions can be manifested through various modes. As“a sign system interpretable because of a specific perception process” (Forceville, 2009,p. 22), mode can be used to directly represent and simulate the analogical process of multimodal metaphor and hence is more prone to the activation of the embodied schema of certain concepts.

As pointed out above in 2.1, mode in semiotics refers to the semiotic vehicle or, more accurately, the signifier or plane of expression, with which it makes a sign perceptible to its interpreters. A sign can be mediated by one or more modes, and a multimodal sign is one which is co-represented by more than one mode. For instance, a cartoon narrative can be classified as aggregation of multimodal physical signs, consisting of gestures, facial expression, movements, as well as other prominent bodily features (like the hair or chin of the President of the United States, Donald Trump), etc. “Multimodality is a semiotic theoretical perspective that facilitates an organized analysis or study of all modes of semiotically significant resources in any given sign” (Umar, 2017, p. 65), the delineation of which contains a significant thought that various modes, if any, are organized semiotic resources, and the different ways of organizing them might encode divergent meanings based on their variety as well as the organization. Such explanatory potential of a sign is called its “affordance”, comparable to the meaning bank of specific signs. For instance,the sign of a “sheep” might be entrusted with different referred meanings, either variably or simultaneously. For a random person, it might signify the quality of obedience, while a biologist might see it as a type of mammal, or a farm owner might just consider it to be something that can be sold for profit, which means that its interpretation seems quite dependent on the cognitive-semiotic situation and the embodied properties depicted,which is particularly true in non-verbal representations. This type of specificity arises from the fact that non-verbal modes can concretely denote an individual member of a category with a detailed and concrete perceptual depiction. So, even the same sign, if modified in different contexts, might carry divergent meanings, for “images naturally depict specific items, including their visual qualia” (Langkjær, 2016, p. 119), and hence the challenge is to simulate and highlight the categorical aspect of certain salient features of these signs.

To realize the goal of perceptual simulation, various modal parameters can realize and, more importantly, highlight the perceptual similarity between the two conceptual domains. By doing so, they might eventually influence the direction of cognitive construal of the multimodal metaphors. According to the differences of operation, there are two different basic ways of perceptual similarity: one is based on the similarity of“sensory” feelings: by virtue of juxtaposing the two entities in multimodal forms and of creating similarity through non-verbal representation, it can consequently provoke the cognitive link between the source and target domains. For example, in Figure 1 below, there are two physical signs, namely, the dragon, referring to Chinese labor and goods, and the worker, representing American industry; the major modal parameters that have been used here to represent the physical signs include shapes, colours, and size. Firstly, the dragon’s body shape is not the same as that of a typical Chinese dragon.Instead, it is quite similar to the dragons of Western cultures. Particularly speaking, the wings, the head, and even the texture are typical bodily features of Western dragons.Western dragons are traditionally antagonistic, therefore the viewer will be led toward a negative interpretation, rather than the positive one traditionally associated with Chinese dragons. The other type is based on “relational similarity”, demonstrating dynamically the similarity of the relations or sequences of completion between two entities, instead of representing directly the sensory similarity. In Figure 1, for instance, apart from the delineation of a single image, the ultimate effect that the whole picture aims to highlight is the unbalanced economic relation between the US and China, which is metaphorically manifested by the visual relations depicted in the cartoon. Specifically, the unequal relation is accentuated by the sharp contrasts between the two entities in Figure 1 in terms of three parameters, namely, “big” vs. “small” in size, “low angle view” vs.“quarter view” in perspective, and “up” vs. “down” in positional relation. Obviously, this metaphor is striving to lead its cognitive subjects to take notice of the inherent similarity of relation, dependent on direct sensory representation of the analogical process in the cartoon. Accurately speaking, the joint efforts of the above parameters exert countereffects on the direction of interpretation of the multimodal metaphor, with the perceptual salience in the outer forms of concepts, and eventually giving rise to a special attention toward the cognitive content.

Figure 1 (http://lalasamurai.blog.sohu.com/49157174.html)

2.3 Cognitive effects of manifested perceptual simulation

In view of the nature and affordances of non-verbal modes, multimodal metaphors are featured with ambiguity in a certain degree, which means the interpretation of the cognitive link between their source and target domains might not be as clear as that of verbal metaphors. More importantly, “the link usually stems from the cognitive subject’s intention” (Zhao, 2016, p. 189); hence, metaphorical relation, in fact, is very much related to the underpinning of that intention, which, if interpreted by the potential audience,might generate satisfying cognitive effects.

The above discussion, as a matter of fact, has already pointed out that the advantages of the perceptual representation of concepts, particularly its cognitive effects, should be extended to the level of intentionality, instead of being limited to perceptual simulation in the form representation. It has to be admitted, though, that multimodal forms, thanks to their more diversified composite elements, can indeed create a more vividly depicted image than verbal expression, corresponding to various properties like size, shape,colour, etc. Nonetheless, through setting and highlighting the perceptual properties,the utmost effect that it strives to achieve is to influence and even restrict the direction of interpretation to the cognitive content of multimodal metaphors, which could be articulated from two different aspects as follows:

First, physical signs frequently take advantage of metonymic vehicles to refer to a hidden meaning, attitude, or stance that seems not so closely related to the forms of signs.For instance, the forms of the bags of some high street brands are not directly relevant to fortune or social status, but they could be metonymically understood as a symbol for social status or fashion. The same is also true in cartoons, whose characters might be highlighted in terms of some perceptible properties, but the interpretation to these traits or features cannot merely stay on the superficial level. In Figure1, for instance, the worker metonymically stands for American industry, as is indicated by the English letters on the body of the “worker”, whilst the dragon is another physical sign, serving as a metonym for China’s industry, which is confirmed by the words on the dragon’s body. As is mentioned above, physical signs might turn to various perceptible features to indicate some lurking ideologies. This figure accentuates some sensory properties of “dragon” and “worker”respectively: the magnified details of the image of dragon, including its giant body size,its fire-red color, as well as the smoke and fire out of its mouth, add many ingredients to the aggressive and threatening nature of the “dragon” depicted here in the cartoon; while,in sharp contrast, the “worker” representing American industry is set as a short, nameless man, who is gradually melting under the threat of “fire” produced by the other actor of the cartoon, the dragon. The perceptible features seem to indicate the dominating status of dragon against the worker.

Second, with the help of relational similarity, multimodal metaphors can emphasize ideas or connotative meanings by manifesting the relations between different physical signs in the cartoon. As is shown in Figure 1, the dragon and the worker are depicted in different parameters, and more importantly, arranged in divergent locations, through which one could infer the so called “genuine” power relation between the two entities, namely that the“Chinese economy threatens the development of American industry”, which can therefore be targeted as the ultimate message that this cartoon aims to express. This further exemplifies the approaches adopted by multimodal metaphors in exerting effects on the cognition of content through a particular design on the perceptual or sensory properties in formal representation, for perception should not merely be considered as a carrier to photocopy the already well-arranged formal construction, instead, the construction or the manifestation itself is an active process, which has already been pre-filled with meaning and intentionality (Violi, 2008). To make it clear, perceptual representation is not a simple reproduction of the objective world. Instead, the process is entitled with particular meaning or significance, which have certain intentional attitudes or stances behind them.

Simply speaking, non-verbal modes create the outer perceptual salience or procedural or relational similarity of certain concepts in specific representations. It is found that sensory organs can strengthen a cognitive subject’s attention to the construal of the cognitive content, as is argued by Zhu Jing (2015, p. 168): “Perceptual senses lead people’s attention directly to his or her own body’s feeling and thus stimulate them to judge the content itself of the stimulus”. More accurately speaking, various modal parameters are involved in joint efforts in the restriction or influence of the direction of metaphor interpretation by virtue of the manifestation of outer properties of concepts.

3. Semiotization: Modularization of Physical Signs in News Cartoons

Embodied cognition theory argues that cognitive content stems from the body format. The structures and activities, etc, are projected onto the cognitive targets or the world around,and are entrusted with particular meanings through bodily experience. Just as Ouyang(2014, p. 3) points out: “it is through body that we understand things, and it is through body that meaning is underpinned”. This practice of meaning generation has been quite time-honoured; it can be traced back to the primitive age, when people gradually acquired the ability to express certain meanings or cultural significance through body parts or gestures, as well by applying as special paintings to their body, conducting ritual dances,etc. These bodily “speech acts” gradually became schematized as stationary physical signs, which lost their original meaning and gradually turned into signs whose meanings are co-determined by the superficial structure, as well as context, and hence they might be able to point to different themes or meanings in different scenarios. Along with the rapid transformation of modern forms of social life, physical signs are manifested in more diversified forms and are applied in a broader scope. Literature composed of words,paintings composed of colours or shapes, music composed of melodies, and even dynamic videos consisting of all the above mentioned modes, are all dependant on physical sign systems as well as their signified meanings to frame and structure certain concepts or theme meanings.

A “semiotic” refers to a thing that can replace another thing in the meaning making process (Zhang, 2014); the basic working mechanism of metaphor is that one thing is experienced in terms of another thing, and therefore metaphor, comparatively speaking,can be considered a special form of substitution, in a certain degree. With this in mind, the frequent presence of body parts in various metaphors can be accounted for as the process of semiotization. It is not so rare to discover the phenomenon of certain concepts or things being simulated by different body parts or images concerned with the body in literary works, as well as in daily communication. For example, in some metaphorical expressions like “the foot of the table” or “the foot of the mountain”, etc., “foot”, whose original meaning is as the organ to walk or stand, has become a physical sign that can be used to represent other concepts. The process of using the “body” for simulation is the process of semiotization. The specific procedure can be explained as “modularization”, namely,delineating the perceptual properties by the body or its activities (Yan et al., 2007). In this process, a unit called a “module” seems critically important in at least two respects:one in that it can be repeatedly used as structuralized formal unit; the other in that it can be flexibly combined based on bodily experience. The principle of this module unit is to express the unknown by the already known, or to generate new semiotics based on existing ones.

3.1 Sources of “modules” of physical signs

The birth of new metaphorical expressions is usually a natural product of the combination of old expressions, for instance, “financial tsunami”, “economic landslide”, etc., and their meanings are, more often than not, metaphorical extensions of the original meanings of the source domain. Similarly, new signs are also built upon the integrating of elements of old semiotics, technically speaking, modularization.

It has to be noted that modularization involves two consecutive procedures: the first of which is the selecting of sources of modules, mainly dealing with selecting appropriate content from the body or its activities; the second is more comparable to the process of combining, aimed at the ways of integrating properties from different sources into a whole. Their respective features determine that the former focuses more on its range or scope, while the latter tends to focus more on the approaches of combination. Although physical signs in a multimodal context still follow the basic rules of modularization, the scope of their sources and the ways of combining various semiotics are more diversified in forms compared with those in verbal discourses, and the process of semiotization and the ways of construal exhibit quite divergent traits against conceptual metaphors.

From the perspective of the scope of sources, the cognitive encoding process of multimodal metaphors, compared with conceptual metaphors, still considers “concrete things” as the main source of modules. Due to the diversified ways and parameters of manifestation, including shape, colour, location, size, etc., the representation can simulate the representation of the bodily schema based on physical structures or organs, and hence the perceptual traits of the cognitive targets can be fully depicted and highlighted in a multimodal metaphor. Visual delineation of concrete things with different modal parameters can only suggest similarity in limited ways, but the figurative implications arising from the multimodal forms cannot be underestimated. Figure 2 exhibits a typical scene where one specific character is manifested in different modal parameters. It shows a close-up of a dragon’s face, whose size occupies a large part of the panel, signifying its dominating status.

Figure 2 (Excerpted from The Economist, Sep. 26, 2015)

In addition, the highlighted details of its facial expression, including the widely-open mouth, sharp teeth, aggressive eyes, and standing hair, very much resemble some symptoms of angriness, which is denied, however, by the verbal expression “smiling like this?” It could be inferred that the dragon strives to make a smile on its face, but all the properties manifested here point to “angriness” or “aggressiveness”, which gives rise to a more ironic figurative implication that China, represented by the dragon, is a dangerous country.

Additionally, the scope of sources of modules for the physical signs can be expanded to certain physical gestures or procedural activities. Although the gestures or activities themselves, more often than not, are not similar in perceptual properties, the introduction of some specific schematized gestures or procedures can underline the relations between source and target, or simulate the similarity in procedures for completing certain activities. The fact that physical gestures or activities can directly construct physical signs for multimodal metaphors is simply because of their repeatable and durable nature.Undergoing the process of repeated application, some physical gestures gradually become a type of physical sign within a certain cultural community, and therefore it can refer to, if plugged into cognitive activities, another phenomenon or thing that is accepted within those specific communities. For instance, a typical scene in a Japanese sumo match is one where two sumo wrestlers squat face to face on the stage. When this representative procedure of the sportive activity is incorporated into a news cartoon in which the two sumo wrestlers, a “dragon” representing China, and a “human wrestler”dressed in traditional Japanese warrior armor, it actually aims to construct the metaphor that “China and Japan are two wrestlers in a sumo match”, striving to highlight their tense relations in terms of the issue of the East China Sea. It has to be noted that in this example it is the connotative signified meanings, fierceness and aggressiveness, of a sumo match that are realized in the metaphorical process. It signifies that cognition,based on the body as it is, actually transcends the body itself and can entertain various types of physical activities, which grants it the productivity and representativeness to structure other concepts.

Figure 3 (Excerpted from The Economist, Dec. 7, 2013)

Even with the same sources of modules at hand, verbal discourse and non-verbal or multimodal discourse might be quite divergent in terms of the representation of the modularization process: In verbal discourses, based on the linearity principle, the physical signs can only be described in temporal sequence, and it might not be possible to fully and accurately represent the sensory perception of the semiotic images. For example, in the verbal expression “her lips very much resemble an oily-colored beetle”, apart from the attribute “oily”, the word “beetle” has no other means to be more vividly delineated; and one has to imagine exactly how “oily” it is, and more importantly, what the beetle looks like. Without accurate clarification on the above points, the metaphorical link between the source and target domains might also be affected by ambiguity to a certain degree.It exemplifies that the representation of modularization in verbal discourses is simply to interpret an image by another one in verbal description. However, this disadvantage seems to be complemented by the multi-sensory forms of manifestation in multimodality. In a multimodal context, each mode, based on its own features, has its own affordances. The pictorial mode, for example, whose semiotic logic is featured with both temporality and spatiality (Serafini, 2010), has a relatively strong temporal and spatial organizing function and can present various elements at the same time within the same frame, guaranteeing that metaphorical images can be more easily perceived. It has to be noted that it is a critically selective and creative process of choosing modules and combining them in particular ways. For one, physical features, surpassing the original physiological meaning,might serve as one type of semiotic that carries certain cultural or symbolic meaning, and thus selecting different physical signs for modularization might exert divergent effects on metaphorical meanings. For another, sensory modes are entrusted with the ability to encompass modules from various sources at the same time, which means even the same physical sign can integrate essences or bodily features from different bodies in the simulation process.

3.2 Embodied modularization of physical signs in news cartoons

Embodied cognition underlines bodily experience or the imagined presence of the “body”in semiotic expression, striving to establish the motivated links between the signifier and the signified, by virtue of visible, appreciable, and motivated approaches to constructing the represented target. It has been argued above that various modules and their possible integration in the modularization process might be entrusted with some symbolic or metaphorical meanings that deviate from their original content. It remains unclear,however, what the hidden cognitive processes are that govern the modularization of physical signs. It has been agreed that most physical signs have more than one possible interpretation in different situations, and “such an extensive semiotic potential of a sign is known as its affordance” (Umar, 2017, p. 65). One specific affordance might uncover some lurking links between a sign and the object it stands for, as in the relation between an image depicting something and the actual thing (iconic) or smoke and a fire alarm(indexical), etc. Therefore, it seems quite important to decipher the relations first to figure out the cognitive process of physical signs in news cartoons. Besides, it has to be mentioned that most physical signs are comprised of various modules that might carry certain meanings respectively, if highlighted in formal representation. For example, a“snake”, as a sign, is often represented as a unified whole by putting different modules together. However, its different modules can also produce divergent emphases on its signified meaning respectively: for instance, a “poison fan” could be used metonymically to represent danger or other situations; the snake-like shape can be used to stand for certain things whose structure or shape resembles a snake. It signifies that not only the unified sign, but also all the constitutive modules, should be considered in terms of the cognitive process.

Modules, as sources of semiotization, have their own affordances. For instance,in Figure 3, the physical sign of the dragon is composed of different modules, which might highlight different affordances in the process of semiotization: the strong muscles indicate its power as a big country; the sharp teeth point to its aggressiveness; the gesture and position that resembles a “sumo wrestler” indicates a state of conflict with others.An aggregation of properties like these contained in one physical sign has granted it the ability to exhibit a signified meaning of complexity. Judged from the perspective of semiotics, the links between the signifier and signified can be categorized into three types,namely, iconic, indexical, and symbolic, all of which can be interpreted by cognitive metonymy.

The relations between sign and the thing it refers to could be a perspective of categorization. Iconic signs are dependent on iconicity to represent the target, which means that one thing substitutes another due to their perceptual similarity to each other(Zhao, 2016). In the genre of news cartoons, the sign is more often than not represented through the visual channel, which presupposes that the iconicity between signifier and signified is direct and clear in perception, just as when Zhao (2016, p. 76) argues that “the first step of semiotization is simulation”. It seems that the iconicity of modules indicates that the sign is supposed to simulate its referent or target, like the characters in Figure 3;the gestures of the dragon and the Japanese warrior are a simulation of a sumo match,metonymically standing for their conflicting relations. However, it has to be noted that a “Chinese dragon” is not an existent creature and consequently it seems not reasonable to judge that the sign of the dragon in figure 3 simulates a “dragon”. In that case, it is the sign that creates and simulates the target, which is particularly true in news cartoons, a genre that is quite dependent on imagination and fictive creation.

Indexicality originates from certain relations, particularly causality, contiguity, or between the parts and the whole, between the sign and its referent, and the role of an indexical sign is to remind the interpreter of the target itself. For instance, in Figure 2,at the sight of the head of the dragon, readers will be able to recognize this character is a “dragon”, which actually is a typical case of part-whole metonymy. There’s another important function of indexical signs in that they grant the referent a certain order of organization. Even the simplest type of indexical sign, for instance, a finger, will specify the direction, movement, size, or range of the cognitive targets (Zhao, 2016). In the genre of news cartoons, this function seems more prominent, since the designer will take advantage of various modal parameters to delineate the sign, size, shape, facial expression, gesture, movements, and even clothes, etc., all of which will contribute to the indexicality of the sign. For instance, in Figure 4, the old man is set to represent the United States, which is achieved mostly by simulating the details of a past image that has already been accepted. In the image of Uncle Sam, the suit and hat, featured with the stars and stripes of the national flag, will metonymically strengthen this reference.

Figure 4 (Excerpted from The Economist, June 11, 2016)

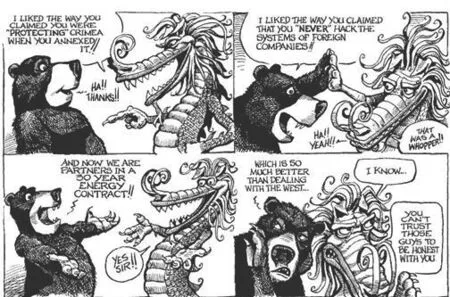

The term “symbol” refers to the type of sign that depends on social convention to decide its relation to meaning. As a matter of fact, conventionality is argued to be the dominating principle for all types of signs, for without social conventions, iconic signs or indexical signs might fail to express their meanings in most cases. For instance, without the social convention that men and women tend to wear trousers and skirts respectively,the iconic signs on the doors of public toilets might cause confusion to their users.The physical signs of symbols are usually paralanguage, including the gestures and expressions of human beings, and a large part of them bear tremendous conventionality,e.g. nodding one’s head means to agree for most cultures and to disagree in some others like Arabian world. In news cartoons, it is very common to see symbols applied to represent specific characters and to accentuate certain connotative meanings behind the scene depicted. Figure 5 is a typical case in point from at least two dimensions. First, the two characters of the panel, a bear and a dragon, are supposed to stand for Russia and China respectively. It is agreed that there are neither any sense of perceptual similarity between the signs and the countries they refer to, nor any relations of causality, contiguity,or between the part and whole between them. Instead, the link is socially conventionalized and the potential reader would activate their schemas at the scene depicted here. Another dimension of conventionality lies in a more micro-perspective: the gestures and facial expressions of the two characters are simply vivid depictions of friendliness between two intimates, like the “high-five”, “secret whispering”, etc. The representation of these modules as physical signs exhibits the claimed companionship between Russia and China against the Western world.

Figure 5 (Excerpted from The Economist, May 24, 2014)

Cognitive metaphor theory is able to explain the coherent structure beneath the different and specific appearances. A central point of metaphor theory is that specific metaphors are not arbitrary but are instances of grounded meaning. Boiling milk,fireplaces, and waves may be trivialized metaphors but they nevertheless work intuitively by activating our basic bodily experience to perceive the power of character emotions.Take a look at the “dragon” in Figure 1 again. In this sign’s modularization process, the original form of a “Chinese dragon” is modified by the artist with some representative modules of the dragon in Western culture, such as “wings” and “smoke”, etc. By presenting all these modules coincidentally, this cartoon realizes the re-semiotization and re-contextualization of the depicted “dragon”, whose original meaning has already been deprived and instead, the affiliated symbolic meaning, viz. aggressive, vicious, etc., will be activated here. By doing so, it can eventually realize the directive or even restrictive effects on the interpretation of the physical sign in news cartoons. The above process has confirmed that amid the process of multimodal metaphor representation in news cartoons,physical signs, entrusted with symbolic or cultural meaning or significance, are integrated by multimodal forms into the cognitive targets, and therefore what has been mapped or projected onto the concept or thing is no longer confined to the superficial body structure,parts, or properties, but actually a specific manifestation of abstract concepts like notions,culture, or aesthetics.

To sum up, physical signs are dependent on metonymic and metaphorical relations to aid their process of semiotization. People, according to their intentionality, select and highlight certain properties by virtue of using and integrating various physical signs. On the cognitive level, these physical signs, entrusted with symbolic meaning,have demonstrated their semiotic nature as resources for representation in a non-verbal discursive environment, and therefore the perceptual properties of the body have, more often than not, connotative meaning, which requires re-interpretation in a specific context.

4. Re-Signification of Physical Signs in Cognitive Context

The body, if as a sign, should no longer be simply considered as a biological being, but as an effective substitution of specific things or concepts which can therefore be used to refer to other things in certain contexts. Undoubtedly, in that case, the original meaning of a physical sign would be replaced temporarily by its referred meaning in the new context.Analogically speaking, the body as a physical sign in various contexts seems to become an “occupied” or “re-occupied” venue, and hence the modularization of physical signs in multimodal metaphor can be classified as a process of re-signification. Generally, resignification refers to the process of borrowing something from one meaning system and then combining it with things from other sources, striving to alter its conventionalized meaning, or to modify a concept by adding new meanings to it (Liu, 2017, p. 182). In terms of the re-signification of the “body”, it refers to in the conversion process from flesh into a cognitive semiotic, and the body is entrusted with interpretations, serving as the symbolic meaning of a physical sign in the cognitive context.

Since “re-signification” is the most basic way of modularization for physical signs, the modules selected and their corresponding connotative meanings, to some extent, determine the symbolic meaning of physical sign. The modules chosen are all from the “body”, either body parts or some procedural representation of certain gestures or activities, but it should not be forgotten that the body is part of the environment in which it is located, which might have at least two implications: for one, the body, as a chain embedded into an environment,has to bear the influence of its surroundings; for another, it is through the body that people begin to know about the whole environment, and therefore not only spatial relations, but even abstract values exhibit the centrality of the body in their cognition; the two reveal an interrelated cognitive relation with each other. In view of the above discussion, it might not be too difficult to infer that the “environment”, from either of the two perspectives,is one of the most important factors affecting the meaning of physical signs and its modularization. In relevant studies on metaphor, most research concerned with the description and creation of environment are conducted from the two different perspectives,temporal and spatial dimensions, which are closely correlated to the construction of the cognitive context for the conceptualization of metaphors. In verbal discourses, the construction of metaphorical context can only turn to words, which might not be able to fully provide the audience or readers with direct perceptual information, and consequently the conceptual details can only rely on people’s imagination. Comparatively, multimodal metaphors, on the other hand, reproduce real scenes in real life from temporal and spatial perspectives as much as possible, and consequently can create more sense of participation in the cognitive context.

From the temporal dimension, the interaction between body and environment is mainly manifested in the body’s linear movement in space, the nature of which, either through horizontal extension in static pictures or by the movements of a camera lens in dynamic videos, is the spatial transfer along the temporal axis. The tracks of the body’s movement can correspond to the general situation, where what the “body” sees, feels, or does is co-present with the sequential demonstration of the spatial environment, and the sensory simulation and dynamicity will give rise to a quite special narrative that appeals to the audience. According to Chen (2017, p. 183), “picture has the ability to evoke the visual experience in reality” and therefore, through the reproduction of a real situation, it can create an inviting atmosphere to cognitive subjects and thus stimulate them to link or even compare the represented content and environment, giving rise to the eventual judgments on emotions or values.

From the perspective of the spatial dimension, the perceptual manifestation of metaphorical context is more expressive in representational forms, which can depict accurately the details of spatial parameters. It has been pointed out that the space which entertains the body has quite strong relations with human emotion (Zhao & Li, 2014);when a physical sign is placed in a spacious and obsolete space, people tend to generate the feeling of loneliness through their reading of the sign; when the scene of strong wind and snow is multimodally represented, it might also give rise to one type of stimulus and sensory experience, similar to that of a cold environment. Multimodal context, through interaction with the environment, grants the body the ability to know the “present”,surpassing the temporal and spatial limitation. The rise and fall of sensory modes and words respectively remind the cognitive subjects of the directive perception of physical signs, making the ambiguous body more clearly reproduced and presented in a specific context.

It has to be noted, however, that there might be another important factor which is, more often than not, overlooked in the representation of the spatial dimension of the multimodal context, namely, the effective application of image. With various individualities and significances, different systems of images, once put in the “to be constructed” cognitive context, will exert significant effects on the manifested scene and its symbolic meanings. For example, one panel in Jimmy’s famous comic book(Figure 6) demonstrates a scene of the interior of a cinema; what makes it different is the application of the image of “snow”. “I”, as the only audience member for the movie,in the flying snow and cold winter wind, and the seats around are also covered by snow,which actually counters the fact that normally wind or snow might not be able to enter an indoor cinema. By doing so, it creates a surrealist scene and at the same time, projects the loneliness and desolation of “my” inner world through the interaction of “my” body and the scenario.

Figure 6 (Excerpted from Jimmy’s comic book The Rainbow of Time)

Image, as the representation of a concept, might be correlated to a series of objects,events, or cultural phenomena (Richie, 2016), and therefore it might encompass ample links to cognition as well as emotion. It is critically important to figure out how to guarantee that the activated properties or cultural meanings are those relevant to the present context. It requires that people turn to various senses to represent and highlight specific perceptual features and relevant context. For instance, in Figure 6, the keynote colour is dark, which, to some extent, might influence the basic mood of the cartoon; in terms of the character in the cartoon, her body takes up a small portion of the whole panel,that is, is put in a corner of the cartoon, which seems not quite prominent against the background, indicating her situation in reality; in terms of the perspective, the character is set with a front view to the potential reader, which is, however, a long shot, indicating her distant psychological and cognitive relation. These modal parameters, though concerned with different aspects, are in joint efforts to create a situation of loneliness and generate a particular meaning for the physical sign.

The cognitive context created in multimodality is not a reduplication of the environment in reality; instead, it is an environment experienced by the “body”. Not only physical-spatial relations like up-down, back-front, etc. are determined on centering on bodily experience, but even the abstract values or notions are also tremendously affected by the body. The interaction between the body and its environment further confirms the embodied nature of multimodal communication. With various sensory modes, the process of re-signification, though able to simulate or modify a relatively embodied temporal-spatial environment, only provides the present cognitive scenario for the body, and what eventually converts the body and its affiliation into a physical sign is socio-cultural influence. A convincing evidence is that the various perceptual modes like colour, shapes, or even the modules of physical signs in certain cognitive scenarios or situations, are quite culturally uploaded, and hence their selection and application in various contexts naturally exhibit certain choices, judgments, or even the highlighting of specific stances or attitudes towards some things or phenomena. This kind of preference will gradually be integrated into the cognitive context constructed here, which will,in turn, be converted as a physical sign carrying certain symbolic meaning through its interaction with the environment. Physical signs, therefore, cannot be fully equated to their references. Although some semiotics, manifested by sensory simulation, have some perceptual similarities to their represented objects, they are not involved in a relation of simple correspondence. Apart from the objects in reality, their reference also points to the more abstract layer of thought.

5. Conclusion

Along with the rapid development of media and information technology, sensory media might be applied more comprehensively in the construction and dissemination of discourses. Judged from the perspective of the multimodal turn, the augmentation of media technology has contributed to a more diversified matrix of ways of representation.Sensory modes, as the basic representation vehicles in the information age, have seen their advantages become gradually clear and highlighted, and have already been assimilated into various ranges of human society; they are influencing, in a large part, and even transforming the way that people view things and the world around them. It is based on this background that the present research proposes to ponder the physical signs in news cartoons, an important genre of multimodality, from an embodied perspective.

Compared with verbal discourses, physical signs exhibit closer relations with sensory perception in multimodal representation. The sensory representations in multi-senses are indeed very powerful in image creation and in temporal and spatial organization, and hence can present the metaphorical image more clearly and vividly. Additionally, the greater advantage of multimodal representation, as is found by this research, is its countereffects as formal representation to the cognitive content. The appropriate and creative use of modal parameters when representing images of certain concepts can successfully divert the attention to the cognitive content and eventually form the oriented interpretation of multimodal metaphors, the result of which further clarifies the inherent relevance between the two aspects of representation, namely form and content.

With the multimodal forms of representation, the scope of sources in the modularization of metaphor has been expanded, and consequently, not only the body itself but also bodily activities or gestures are included in the range of modules for physical signs. It must be noted that the complexity of physical signs in multimodal metaphors of news cartoons,based on sensory modes’ spatial and temporal organizing ability and the modularization approach, is strengthened compared with that in conceptual metaphor, because in multimodal discourses, even one specific physical sign might encompass modules from various sources, determining its complexity both in meaning composites and stronger expressiveness. In addition, modularization being the basic way of semiotization of physical signs, the module selected will in a large part determine the symbolic meaning.The meaning of a module that comes out of the body actually stems from its interaction with the environment. In a multimodal context, metaphor can turn to sensory modes to represent, as much as possible, the environment in the modularization process from the dimensions of time and space, and thus contribute to a cognitive context with a stronger sense of participation. The discovery of perceptual representation on the cognitive level reminds us of the fact that the dimension of senses should not be overlooked in studies on embodiment, and above all, researchers are recommended to take the integration of the various dimensions of cognition into account, which might help generate a more thorough and multi-layered understanding of embodied cognition.

Barsalou, L. W. (2010). Grounded cognition: Past, present, and future.Topics in Cognitive Science,(2), 716-724.

Cao, X. Q., & Gao, E. (1973).The story of the stone(Vol. IThe golden days) (Trans., D. Hawkes).London: Penguin.

Chen, H. Y. (2017). Visual rhetoric and political propaganda in new media era.Journal of Southwest University for Nationalities, (1), 179-183.

Connell, L., & Lynott, D. (2011). Modality switching costs emerge in concept creation as well as retrieval.Cognitive Science, (4), 763-778.

Forceville, C. (2009). Non-verbal and multimodal metaphor in a cognitivist framework: Agendas for research. In C. Forceville & E. Urios-Aparisi (Eds.),Multimodal metaphor(pp. 19-44).Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Han, D., & Ye, H. S. (2014). Important embodied in weight: Weight’s experience and representation in embodiment perspective.Advances in Psychological Science, (6), 918-925.

Jamrozik, A., McQuire, M., Cardillo, E., & Chatterjee, A. (2016). Metaphor: Bridging embodiment to abstraction.Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, (4), 1080-1089.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1999).Philosophy in the flesh: The Embodied mind and its challenge to western thought. New York: Basic Books.

Langkjær, B. (2016). Problems of metaphor, film and visual perception. In K. Fahlenbrach (Ed.),Embodied metaphors in film, television and video games: Cognitive approaches(pp. 115-128).New York: Rutledge.

Li, H. W., Wang, X. L., & Tang, X. W. (2008). Representation, qualia and verbal thinking.Journal of Zhe Jiang Univeristy (Humanities and social sciences),(5), 26-33.

Liu, H. B. (2017). Emoticon culture: Body expression and identity construction under the power transference.Yun Nan Social Sciences, (1), 180-185.

Long, W. H. (2016). Cognition, body and environment: New advances in cognitive psychology.China Journal of Health Psychology, (1), 145-147.

Luo, Y. H. (2016). Sensory story: Technology—The link among media and sensory experience.Journal of Beijing Film Academy, (2), 73-76.

Ouyang, C.-C. (2014). The Metaphor body: The media of the visible and the Invisible.Foreign Literatures, (1), 11-18.

Richie, L. D. (2006).Context and connection in metaphor. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Serafini, F. (2010). Reading multimodal texts: Perceptual, structural and ideological perspectives.Children’s Literature in Education, (2), 85-104.

Solomon, K., & Barsalou, L, W. (2004). Perceptual simulation in property verification.Memory &Cognition,(2), 244-259.

Sun, Y. (2010). A research into the motivation of experiential philosophy and cultural idiosyncrasies in the domain of English-Chinese emotion metaphors.Foreign Language Education, (1), 45-54.

Sun, Y., & Zhang, P. L. (2016). Embodied philosophy and cultural origin of similarities and differences in clothing metaphors between English and Chinese.Journal of PLA University of Foreign Languages, (1), 45-53.

Sun, Y., & Zhou, J. (2015). An insight and exploration of cognitive metaphors in Chinese and English friendship.Jianghuai Tribune, (5), 166-170.

Tan, Y. S. (2016). Schema-instance and dynamic construal in metaphor creation: Exemplified by the explicit metaphors inFortress Besieged.Foreign Languages and Their Teaching, (4),96-105.

Umar, A. (2017). A socio-semiotic perspective on Boko Haram terrorism in Northern Nigeria.Language and Semiotic Studies, (3), 60-76.

Violi, P. (2008). Beyond the body: Towards a full embodied semiosis. In D. Geeraerts, R. Dirven,& J. R. Taylor (Eds.),Body,language and mind(Vol. 2) (pp. 241-264). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Yan, M., & Qiu, P. X. (2007). Pictographic wushu: A dynamic cultural symbol expressed with body movements.Journal of Shanghai University of Sports, (4), 48-52.

Yin, R., Su, D. Q., & Ye, H. S. (2013). Conceptual metaphor theory: Based on theories of embodied cognition.Advances in Psychological Science, (2), 220-234.

Zhang, X. H. (2014). Physical action and symbol evolution.Theory Monthly, (3), 41-44.

Zhang, Z. C. (2014). On symbolization mechanism of body cognition.Jianghai Academic Journal,(2), 30-38.

Zhao, X. F., Li, X. W. (2014). The multimodal metonymic construction of emotion in the rainbow of time: A perspective of cognitive poetics.Journal of University of Science and Technology Beijing(Social Sciences), (6), 1-7.

Zhao, Y. H. (2016).Semiotics: Principles & problems. Nanjing: Nanjing University Press.

Zhao, Y. H. (2017). Formal intuition: The starting point of phenomenology of signs. In H. L. Tian& X. Yu (Eds.),An interdisciplinary study on semiotics(pp. 72-87). Tianjin: Nankai University Press.

Zhou, P. Y., & Christianson, K. (2016). I “hear” what you’re “saying”: Auditory perceptual simulation, reading speed, and reading comprehension.The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, (5), 972-995.

Zhu, J. (2015). The body sense mechanism of leisure aesthetics.Social Science Journal, (2),168-172.

杂志排行

Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- Grammar, Multimodality and the Noun

- The Logic of Legal Narrative1

- Complementiser and Complement Clause Preference for Verb-Heads in the Written English of Nigerian Undergraduates

- Towards a Semantic Explanation for the(Un)acceptability of (Apparent) Recursive Complex Noun Phrases and Corresponding Topical Structures

- Developing Mathematics Games in Anaang

- Identif i cation by Antithesis and Oppositional Discourse Reproduction in Chinese Space of New Media