Grammar, Multimodality and the Noun

2018-01-25DeluZhang

Delu Zhang

Tongji University, China

1. Introduction

When Halliday wrote his article, “Grammar, society and the noun”, the world of linguistics focused mainly on “the internal workings of the linguistic systems in its specific manifestations in languages and dialects”, more specifically, on syntax and morphology, i.e., the form of language, with the social background of language being rarely considered. Therefore, it was very significant to study the contextual and sociocultural aspects of language so that language could be interpreted in terms of the meaning it realizes. Now, fifty years later, the focus of linguistics has been shifted to the study of discourse and meaning in its context. However, in some areas of study, it seems that it goes far in the opposite direction: we begin to study discourse and meaning without taking form into consideration, that is, grammar and its units as formal items are not taken into consideration any more. The study of discourse and meaning now is not“based on solid ground”, to use Halliday’s words (Halliday, 1994). This is the case in some theories of discourse analysis in which grammar that realizes text is not analyzed at all. It is also the case in multimodal discourse analysis, it seems, as Kress and van Leeuwen (2006) say, “Multimodal grammar is not studied the same way as language grammar in which we have to find out the sentences, clauses, nouns, verbs, but they are functioning as wholes.”

However, analysis is characterized by cutting wholes into parts, that is, “a class[is] divided into segments, then these segments as classes [are] divided into segments,and so on until the analysis is exhausted” (Hjelmslev, 1943/1963). Here, the ‘class’ is a category of the unit of text, and the ‘segment’ is a unit of the text. A multimodal text is no exception. It should be able to be divided into its parts, which are further divided into parts until they are not able to be further divided any more. In fact, this is the case in the analysis of the image in Figure 2.1 in Kress and van Leeuwen (1996/2006, p. 45),in which two British soldiers with guns are approaching the aboriginal people who sit or stand leisurely, unaware of the approaching danger. Here in the image, a unit of text in the image is analyzed as a process which consists of participants, such as Actor and Goal,and circumstances. How can you call something an Actor when there is nothing to realize it at all, or when it is still indivisible from the whole? For example, in Figure 2.1 in Kress and van Leeuwen (1996/2006, p. 45), the two people with guns are the participants, the Actor, while the people who sit or stand leisurely, unaware of the approaching danger, are also participants, i.e. the Goal. It means that in the image, we can identify functions as participants; that is, they are parts as functions in a functional structure. Although there are no formal labels for them, there are clearly individual human being shapes or images there.

In language, participants are typically realized by nominals or nouns; why can’t we identify them as nouns in the grammar of multimodal discourse? Probably, it is not that they cannot be classified as nouns, but that it is not the time yet to classify them as nouns as there is not enough evidence to support such a claim, and there are still several issues to be dealt with. First, in multimodal discourse, the participants identified in the images, for example, are merged together with their actions and individual characteristics. The same participant may perform different actions, be shaped in different ways, and have different distinct characteristics. Should it be recognized as the same participant or as different ones? How are the different processes recognized in the text? Secondly, multimodal discourse is not only composed of different modes, but it is also multi-dimensional. It is much more difficult to identify the participants in images in terms of their total figures and boundaries than that in language, since language is linear. Thirdly, image is an icon, which resembles the referent (object), so a formal category is unnecessary for the interpretation of the sign.

Yet, since we already have a functional grammar of visual design developed by Kress and van Leeuwen (1996/2006, 2002), we have had a good start in pursuing such a cause.Although they claim that “they are functioning as wholes”, we can still differentiate participants from processes and circumstances. These are of course functions in the multimodal image, but we can find out the segment of the form of the image from which they are derived. For example, in Figure 2.1 in Kress and van Leeuwen (1996/2006, p.45), although there are myriads of things in the picture, we can clearly identify human figures, and also other objects: in the foreground are two men holding guns marching forward; farther away are several men sitting or standing, talking to each other; we can also find trees, the moon, and the landscape, etc. All these can be recognized as entities,that is, they can be regarded as nouns. However, what is significant in the image is generally what is in the foreground: thetwo menholdingguns [attack] theother fivefarther awayin the evening.

Multimodal noun as a formal category has been mainly studied by formalist theories.The first is that of the formal art theory (Arnheim, 1974, 1982), the language of which is grounded in the psychology of perception. “Participants are called ‘volumes’ or ‘masses’,each with a distinct ‘weight’ or ‘gravitational pull’. Processes are called ‘vectors’ or ‘tensions’or ‘dynamic forces’” (Kress & van Leeuwen, 1996/2006, p. 49). Secondly, in shape grammar, which is used for design in various areas, such as painting and sculpture, shapes and subshapes are the components used to generate various types of designs (Trescak et al.,2012). These shapes and subshapes have the characteristics of nouns in such a grammar.Thirdly, in graph grammar of visual language, which is used as a suitable formalism to describe the abstract syntax of visual modeling languages, graphs, including the notational symbols and graphical representation, and visual objects such as icons or elements are the components of the graph grammar of the visual language, which are used in a diverse set of traditional engineering domains including electronic circuit design, chemical engineering,and architectural design (Grunske et al., 2008).

In Kress and van Leeuwen (1996/2006), since they do not claim to study visual grammar in the same way as that of language, they do not recognize nouns and verbs in visual grammar, but they can still find noun-like elements: “If we wanted to translate this into language, we could say that the boxes are like nouns, the arrows like verbs (e.g. ‘send’or ‘transmit’), and that, together, they form clauses (e.g. ‘an information source sends[information] to [a] transmitter’)” (Kress & van Leeuwen, 1996/2006, p. 48).

Similar statements are made in various parts of the book, such as: “…what in language is realized by means of syntactic configurations of certain classes of nouns and certain classes of verbs is visually realized, made perceivable and communicable, by the vectorial relations between volumes. In Arnheim’s words, ‘We shall distinguish between volumes and vectors, between being and acting’ (1982, p. 154)” (Kress & van Leeuwen, 1996/2006,p. 50); “But, and this is what matters for the purpose of identifying participants, these‘volumes’ are perceived as distinct entities which are salient (‘heavy’) to different degrees because of their different sizes, shapes, colour, and so on” (Kress & van Leeuwen,1996/2006, p. 62); “…the structure of English, with its lexical distinction of verbs/processes and nouns/objects, may have acted as a model for a semiotic schema. So arrows as vectors/processes and boxes as participants/nouns may be a more or less unconscious translation from language into the visual” (Kress & van Leeuwen, 1996/2006, pp. 65-66).

In this sense, Kress and van Leeuwen’s (1996/2006) study makes it possible to study the nominal category functionally as a constituent element in the visual grammar, or as an independent element that realizes the component of the text structure.

So, in the following, we will first study the characteristics of the noun, and then try to study if nouns can be identified in terms of types of signs, the level of the semiotic system, and multimodal structures.

2. Characteristics of the Noun

Noun as a linguistic category is familiar to everyone. The English wordnouncomes from the Latinnōmen, meaning “name” or “noun” (Lewis & Short, 1879), a calque of the Ancient Greekónoma(also meaning “name” or “noun”) (Liddell & Scott, 1897). Word classes like nouns were first described by Pānini in the Sanskrit language and by Ancient Greek grammarians, and were defined by the grammatical forms that they take. In Greek and Sanskrit, for example, nouns are categorized by gender and inflected for case and number.

A noun can be defined as a word that functions as the name of some specific thing or set of things, such as living creatures, objects, places, actions, qualities, states of existence, or ideas. Linguistically, a noun is a member of a large, open class whose members can occur as the main word in the subject of a clause, or the complement of a verb or preposition.

Nouns can be said to have the following characteristics: firstly, a noun is used“to name classes of objects” (Halliday, 1967, p. 53). In this sense, we can find that if something is called a noun, it must refer to something else, an object, or an entity, and entities should also include abstractions like concepts and ideas. IfPeter, duck, engine,andsandare nouns, thenideology, materialism,andworking classare also nouns.

Secondly, a noun is merely a name, not the object itself. For example,dogrefers to a kind of animal, and so stands for it, but it is not the animal itself.

Thirdly, nouns can stand independently as members of a class (Halliday, 1967, p. 53),such as those items in the dictionary. When a noun is found in a structure, it has a class label in a formal structure.

Fourthly, however, nouns also have functions in the semiotic structures. Its features as a noun come from its function(s) in a structure in the context of a situation. For example,in transitivity, nouns typically function as participants, such asActor, Goal, Range,Beneficiary,etc.

Fifthly, a noun is a relatively regular and stable category; that is, when a sign is called a noun, it will be called a noun wherever it occurs. This is the case even when it occurs in a dictionary or word list.

Finally, a noun is an abstract category. As a category, it does not just refer to one specific object (except perhaps for some proper nouns), but a range of things that share certain features in common, from the most typical (the prototypical) to the most peripheral.

For a linguistic noun, these features are not difficult to recognize, but for a semiotic noun in general, it becomes more difficult, as nouns in other semiotic systems may exhibit very different characteristics, which will be discussed in the next section.

3. Types of Sign and Noun

Firstly, there are different types of signs. The linguistic sign is just one of them. Pierce(Pharies, 1985, pp. 34-41) classified signs into three types: icon, index, and symbol. An icon is a sign which stands for something merely because it resembles it, for example, the icon of a horse stands for the animal horse as they resemble each other. An index is a sign which signifies its object solely by virtue of being really connected with it. For example,the natural cause-and-effect relationships can be found betweenrainandwet street, andbowed legsandcowboys, etc. A symbol is a sign which refers to the object it denotes by virtue of a law, usually an association of general ideas, which operates to cause the symbol to be interpreted as to referring to that object. For example,is called a ‘tree’ in English, ‘arbor’ in French, and ‘shu’ in Chinese simply by convention; that is, there is no inherent association between the symbol (as medium) and the object it denotes.

While we believe that all the three types of signs share the features of likeliness,association, and convention, each highlights a particular one. Icons highlight likeliness,indexes association, and symbols convention. So a symbol is associated with its object mainly by convention, something Saussure (1915, p. 100) calls the arbitrariness of the sign. A symbolic noun should have all the features of a noun we talked about above (see 2.0). It is a name for a class of objects as the association between the sign and the object is not one-to-one, but one-to-many, that is, one to a class of objects. It will be relatively stable, and abstract as the association is regular and routinized in history. It will also be a category that can be independent of the context and can have functions in use. A linguistic sign is of this type, so is that of sign language, Braille, Morse code, etc. There are also non-linguistic signs, such asroseas a symbol of love,whiteas a symbol of purity, andblackas a symbol of mourning in some Western societies. These are symbols,not icons or indexes, because they may refer to different objects in different cultures. For example, white indicates purity in some Western cultures, but mourning in some of the East.

The question that should be considered here is: “Is ‘rose’ a noun which refers to the concept of love?” It shares most of the features of the linguistic sign, but its material realization is essentially different from it. A rose is not designed or does not grow to signify love, but is itself a plant, a real material object. If we consider it a noun, then the concept of noun is extensively broadened. So we need to make a decision here.

An indexical sign exists by virtue of its association between the cause and the effect.Smoke indicates the existence of a fire. Here, the indexical sign as a noun lacks many of the features of a linguistic sign as a noun. First, it may not be more general or abstract than its object. Smoke and fire are at the same level of abstraction. Secondly, they are not connected by convention, that is, not by human intervention, but by nature. This means that the insertion of a concept of the noun to one of the pair is not quite necessary. Thirdly,the media that realize them are not different from each other, but are of the same object,only they focus on different aspects of the same object. For example, smoke and fire are of the same event. Should the smoke be considered a noun which indicates a fire? Again,we need to make a decision.

Icons are, inherently, visually the same as or similar to their referent. Again they may lack several of the features of the linguistic sign as a noun. Firstly, they are not associated by convention or association, but by visual likeness. As a result, we do not need anything else to interpret the sign, but its likeness. Secondly, there are different degrees of generality or abstractness between the sign and its referent in the iconic sign. A photo of a tree will be almost exactly the same as the tree itself, but the sketch of a tree in a painting or in a figure will be very abstract, even closer to a symbolic sign as a noun. Thirdly,in terms of the medium that realizes it, it ranges from two dimensional images to three dimensional sculptures, or moving images in time and space in animations. Anyway, as the sign and its referent are alike, it seems unnecessary to call the sign a noun denoting its referent. For example, it would seem absurd to call the picture of a man a noun denoting that man. However, since they are signs, and not the objects themselves, there will be differences between the sign and the object. So whether we should call the sign that denotes an object (thing, person, concept, etc.) that is similar to it a noun or not depends on how we intend to design our theory.

In sum, there are problems in determining the status of the noun in all of the three types of signs. If we take the linguistic noun as the basic criterion to determine the status of the noun in other non-linguistic semiotic systems, then most of the non-linguistic signs denoting objects would not be considered nouns. However, as all signs are in semiotic systems that have form for the realization of meaning, we need to find out the classes or categories of the signs so as to describe the semiotic system by relating the meaning that the sign denotes to the medium that realizes it. In that case, we need lexis and grammar to describe them. In lexis and grammar, the category of the noun is indispensable for most of the semiotic systems.

4. Nouns in Different Types of Semiotic Systems in Terms of Levels

All semiotic systems are systems of meaning, or meaning potentials in a culture. However,they are also different from each other in various ways, such as in terms of medium types,sensory channels, strata involved, etc. For example, semiotic systems can be dynamic or static in terms of the characteristics of the media that realize them; semiotic systems can be of various dimensions, such as linear (oral language, written language), two dimensional (image), three dimensional (sculpture), or even spatial-temporal (animation,film); they can also be of different sensory channels, such as visual, auditory, tactile, etc.,or of different strata (two-level, three-level).

While all these may be relevant for the classification of signs into classes, we focus here on the semiotic systems of different strata: the two-level system and the three-level system. The two-level system is a simple system, which consists of individual signs directly related to meaning (Halliday, 1975, pp. 12-13). Machin (2007, p. 3) uses the following model to show the relation between the sign and the meaning:

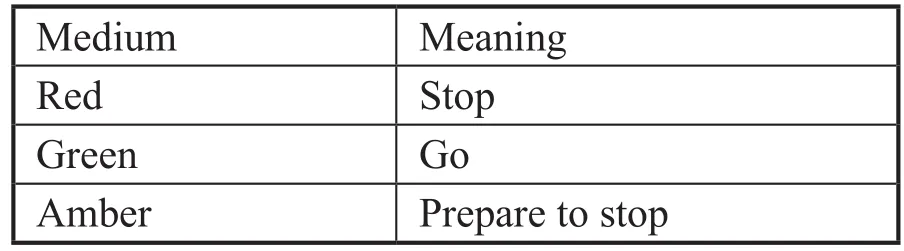

Here, “sign is simply the signifier” (the medium of the sign), and it “has a signified (a sign-vehicle that has an object)” (Machin, 2007, p. 3). For example, the picture of a lion simply refers to a lion. It can form an open system which consists of numerous members like the lexical system of a language. However, for some systems of a symbolic kind,they can form closed systems, such as the traffic light system, which mainly consists of three items:green, red,andamber. Each item is directly related to a meaning. There is no lexicogrammar between them:

Table 1. The relationship between medium and meaning

As there are only medium and meaning, this is called a two-level system. In such a system, there is no lexicogrammar, so it is not possible to talk about the status of the noun in such a system. However, it is considered a two-level system simply because it is not necessary to insert a lexical level here as there is no grammar in such a system. Actually,each sign can be considered a word which links the medium with its meaning. If the word is nominal, then it is a noun. For example, all the three signs:red, green,andambercan be considered nouns. The only difference between such a system and a three-level system like language is that it does not have a grammar. This means it realizes the meaning of the text by individual items, such as in the traffic light system, the text will be: “green—amber—red” in recursion. A word functions the same way as a sentence in a three-level system.

If the signs in a two-level system can be considered lexical items, it is not a two-level system any more, but a simple three-level system with only lexis in the lexicogrammar.In such a system, we need to determine which class the lexical items belong to in terms of the essential features of the object they refer to, that is, whether they are more like actions or things. For example,red, green,andamberare more like objects than actions, so they are nouns, rather than verbs, as is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Traffic light system with lexis and class

A three-level system is amore complex semiotic system which can be represented like this:

In the complex system, Halliday refers to lexicogrammar as something abstract that is wedged in between meaning and substance, or between meaning and the phenomenal(since the sign resides in the phenomenal, or real, world) (Machin, 2007, p. 3). The point is that the relationship between sign (substance or medium) and meaning, although regular and systematic, is not as direct as when there is lexis in the system, but is associated indirectly through the recombination of signs to create new signs. Here, the status of the noun also becomes more complex. What is more significant here is the nominal rather than the noun, as the noun is only the class feature of one rank of the lexicogrammatical system, namely, the word rank. Above the word rank, we have the nominal group, which functions in a process, a clause, as participant.

(1) Boy is male.

(2) A boy is a male person.

Here, in (1), the new sign “Boy is male” is created by combining the three words together:boy, is,andmale, in whichboyis a noun,maleis an adjective, but both are participants and nominal. In (2),a boyanda male personare also both participants and nominals, and in both, there is a noun category:boyandperson.

Table 3. Contrast between two-level systems and three-level systems

In linguistics, we often know the system, and so we learn to know how we make choices from the system to make meanings and so produce structures. However, in multimodal discourse analysis, we often have the discourse first, but we don’t know the system behind it. In this case, we need to study the system from the discourse. As we are not familiar with the non-linguistic semiotic systems, we are not sure of the class nature of the items in them. The only way to find that out is to examine their functions in the discourse. Nouns are the major category of the nominal or part of the nominal group.Nominals function mostly as participants in transitivity structures.

However, the function of the item can only show the general characteristics of its nature as a class member; it cannot determine its status as a noun. That is, it only shows that it is a nominal category, but whether it is noun or not is determined by many additional factors, such as whether it is an item or a group of items, an entity or a quality,direct or metaphorical. In this case, it seems, we need to consider both its function in the structure, and its internal characteristics.

Firstly, in terms of functions of the items in semiotic systems, all participants in the transitivity structure are nominal in nature. We can determine their nominal status instead of verbal status by their function in transitivity structures. However, some participants are typically qualitative, such as the attribute in an attributive relational process,and most of the participants are realized by groups, especially in language. In visual grammar, differences in colour may serve as a quality of the participant that can make a difference between participants. A participant in red may be in contrast to a participant in blue, which have the same function in the transitivity structure, but can have different goals. It means that the colour is qualitative and may result in different characteristics of the participant. The number of entities and whether they are of the same type or not are also relevant here as this can show whether they should be regarded as a word or a group. For example, in Kress and van Leeuwen (1996/2006, p. 45), two chargers with guns form a group instead of one noun. It is the same for the Goal, which consists of several people.

Apart from the function of the item in the semiotic structure, other internal characteristics are also relevant in determining the status of the noun of an item.These include the essential features of the noun: as the name of a class, as an entity, as conventional category.

First, it is an entity, not a process. This is actually shown in its function as a participant,whether it be a noun, a nominal group, or a nominalization.

Secondly, it must stand for a class rather than an individual item. In Figure 2.1 in Kress and van Leeuwen (1996/2006, p. 45), if we say the image of the two British soldiers holding guns is a nominal group, it stands for human beings in general, not Peter and John as two individual men. This is clearly shown in Figure 2.3 in Kress and van Leeuwen(1996/2006, p. 49), in which the two men are reduced to an outline as an abstract entity.

Thirdly, it must be a conventional and regular category. This is probably the most difficult aspect, to consider the image of an entity as a noun, as there are no conventionalized regularities to determine which is a nominal category out of this specific image, although humans always have the competence to come up with such abstractions such as the schematic drawings in Kress and van Leeuwen (1996/2006):

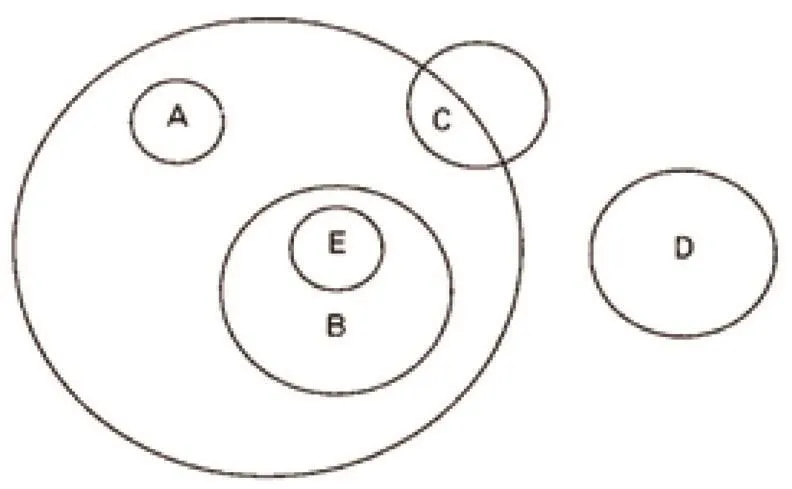

(1) For conjoining participants (Kress & van Leeuwen, 1996/2006, p. 52), see Figure 1.

Figure 1. Conjoining participants

(2) For inclusive analytic structures:

Figure 2. Schematic drawing of inclusive analytic structure

The status of a noun can be based on these abstractions, although how we come out with such a schematic structure needs further research, especially if they are conventionalized or regularized.

Another factor that complicates the research is the symbolic or metaphorical association between the sign (the medium, expression) and the meaning (the content). The sign refers to something that resembles it, but at the same time, it also refers to something else, a meaning that is connected with it by convention. That is, the sign is both an icon and a symbol. Is the meaning of love mainly associated with the image or with the real rose? It seems that as a conventionalized sign, the association was first established between the real rose and the concept of love, and then it was attributed to anything that was associated with the flower, such as an image, picture, the word, etc. In this case, the whole icon sign (the expression with its content) becomes the signifier, and then it is related to the signified, the concept of love.

5. Nouns in Multimodal Text

However, we are mainly concerned with the study of nouns in multimodal discourse.In order to do that, we first study the status of nouns in different semiotic systems other than language, especially that in what are called the two-level system and the three-level system, and in different types of sign systems. We study it this way simply because we are not familiar with the systemic nature of the noun yet in different semiotic systems, and we have to go in an opposite direction, from instance to system, or from text to system. In this way, we need to study how nouns behave and can be recognized in multimodal texts.

All texts, whether multimodal or not, are semantic constructs: semantic configurations of ideational, interpersonal, and textual meanings, motivated by the context; the context of culture—conventions, beliefs, and general ways of doing things, and the context of situation—the field, the tenor, and the mode.

Meanings are then realized by the choice of modes available in the culture. First,in different cultures, there might be different modes available for the members of the community within that culture. For example, in some developed cultures, apart from spoken language and written language, there are also advanced technological modes, such as the Internet, multimedia technology, Powerpoint presentations, etc., while in some developing cultures, there are mainly body gestures and postures available. Secondly,different cultures may also highlight or prefer different modes. For example, gestures may be favoured in face-to-face communication, or people might expect others to be more reserved, using as few gestures as possible. Thirdly, different modes have different affordances or meaning potentials, and so are more suitable for realizing particular types of meanings. For example, bright colors are more suitable for traffic direction than written words, images are more suitable for presenting real objects, and written words are more suitable for recording detailed events and historical facts, etc.

In this sense, which modes should be selected for constructing multimodal texts are conditioned by various factors: cultural preference, mode availability, and the affordance of the mode. Different modes will have different functions in the multimodal texts. Not only might different modes realize different semantic structures, but they also might combine to construct the same semantic structure. Nouns from different modes may be chosen to realize different functions of the multimodal structure.

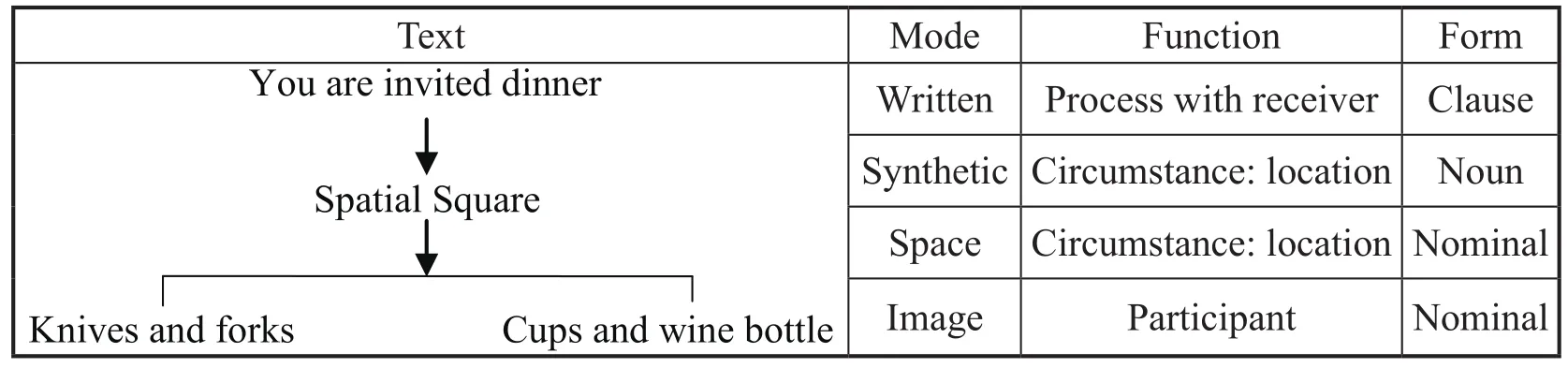

For example, in Figure 1.3 in Kress and van Leeuwen (1996/2006, p. 26), there is an image of invitation letter in which there is a rectangle frame with two cups and one bottle of wine in the centre, a knife and fork at each of the four corners, and the words “You are” at the top and “invited” at the bottom. To anybody without the cultural knowledge,the image is simply a square with dinner facilities in it. However, any body familiar with the culture will know that it is an invitation to a party. Here, at least three modes are used to construct the discourse: the written words, the images of facilities for the party, and the spatial structure of the image. The written mode is the dominant one which determines the text type as an invitation to a party. The spatial mode and the visual mode together realize the function of ‘location’ in the transitivity structure, while the location itself is composed of two modes: the images of party facilities—cups, wine bottle, spoons and forks, and the spatial structure, which may suggest spatial arrangements for the party, spoons and forks for eating and cups and wine bottle for drinking.

But there are no processes explicitly shown in the multimodal text. They are actually implied in the relations between the elements in the text. They form an analytic structure:the whole consists of parts—the dinner is composed of food (knives and forks) and drinks (cups and wine bottle) at a place (spatial square). The discourse structure can be represented as in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Nouns or nominals in multimodal dinner text

Circumstances in language are adverbial in nature, generally realized by adverbs and prepositional phrases. But in the visual design, circumstances are manifested as nouns,called ‘secondary participants’ by Kress and van Leeuwen (1996/2006, p. 72). They are regarded as secondary participants simply because they are related to the main participant not by means of vector, but by other relations: location, manner, time, causeand-effect, etc. In the present example, the Actor (covert) is mainly related to the Goal by circumstance of location.

In the classificational process, the relations between the participants are of two types:those between superordinates and subordinates, and those just between subordinates.The process is usually realized multimodally, especially by the written mode and the visual mode, in which the relation is manifested visually. In Figure 3.2 in Kress and van Leeuwen (1996/2006, p. 81), there is an advertisement of Xpose Range watches, in which we can find nine fish with seven of them carrying a watch around their bodies, and on the top, there is a noun phrase “A lot more watch for your money”. Contextually, it is an advertisement of Xpose Range watches. The text is composed of mainly two modes: the written mode and the visual mode. The written mode provides guidelines for the image in two aspects: (1) it shows the purpose of the ad by a nominal group—a lot more watch for your money. (2) It provides information for the access of the watches in terms of price and correspondence:The Xpose Range of watches by Sekonda from £19.99. For your nearest Seconda stockiest please call 01162494007.www.seconda.co.uk. At the same time, in the multimodal grammatical structure, it also provides a superordinate for the classificational process.

The images are made up of fish with watches on them. The classificational structure is composed of fish with watches. The text and modes, function, and form can be shown in Figure 4:

Figure 4. The noun in a multimodal watch text

From the above examples, we can see that the category of the noun or nominal can be found in the items that realize the functions of participant and circumstance.

6. Discussion: Are There Nouns in Non-Linguistic Semiotic Systems?

From the above study, we can find that there are noun-like elements in multimodal texts both in terms of the functions of elements in the grammatical structures and the characteristics of the noun itself.

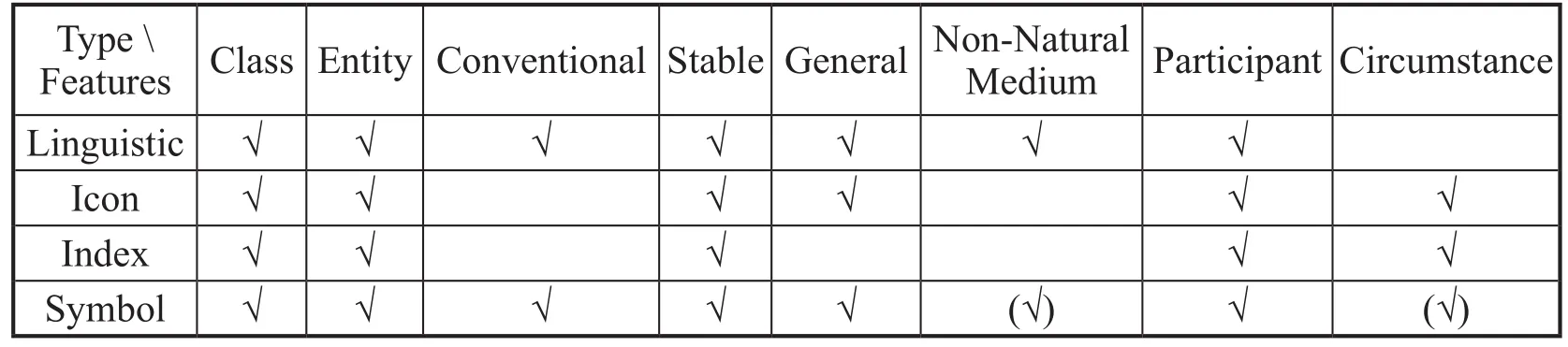

In terms of non-linguistic semiotic systems, we can find noun-like elements in both the so-called two-level systems, and the three-level system, in all of the three types of signs: visual, indexical, and symbolic. At the same time, we can find noun-like elements that realize the functions of participant and circumstance. But there are also indeterminacies here as all of them are noun-like, but are not exactly nouns like those in human language. It means that they share many features with the linguistic noun, like referring to an entity rather than an action, being an abstract category, the schematic drawing of an object, and a conventionalized and stable category like the traffic light signs. At the same time, they also have their unique features that make them unlike the noun. For example, some of them are not designed as signs, such asroseas a sign of love.Roseis a sign, but it is also a plant. Some of them are similar to their referent, like the icons. Some of them are actually the same thing as the referent, such as the indexes. Many of them are conventional and regular enough as a stable, general, and abstract category,like the linguistic noun (see Table 4).

Table 4. The features of the linguistic noun and the noun-like element in non-linguistic semiotic systems

The next question is, should we establish the noun as a formal category for multimodal discourse analysis?

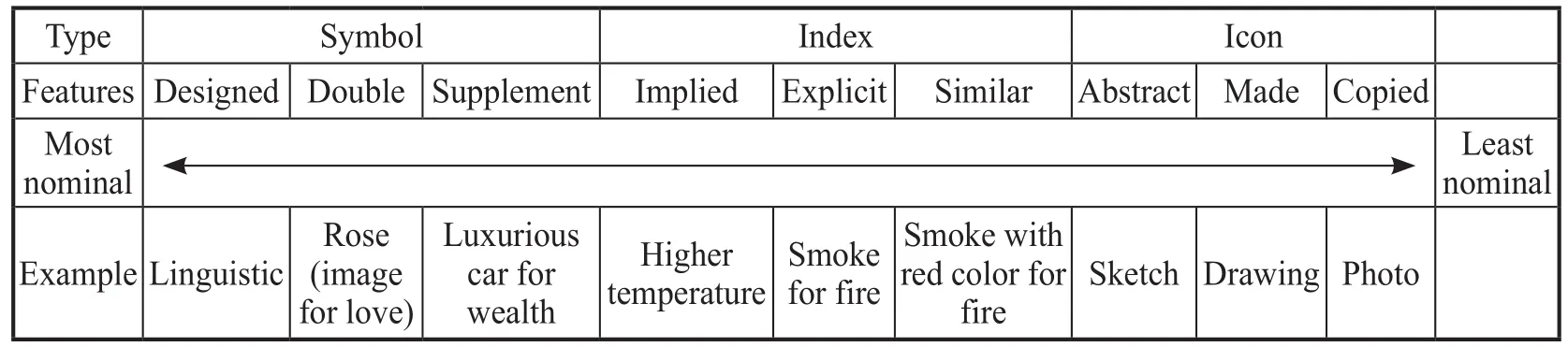

As in linguistics, where we need to develop a category of noun for the description of the linguistic system and language structure, in multimodal discourse analysis, we also need to develop a category of noun-like elements for the description of non-linguistic semiotic systems and the multimodal discourse. However, the noun-like element in nonlinguistic semiotic systems and in multimodal discourse is both similar to and different from the linguistic noun. For its similarity to the linguistic noun, it is plausible to establish such a category in multimodal discourse, but for its difference from it, we should not use the same concept. A more general concept is needed as it not only includes the noun-like element in non-linguistic semiotic systems, but also the linguistic noun. In this sense,the concept of the nominal is preferred rather than of the noun as it is more general,embracing both nouns and nominal elements above the noun in rank and more abstract,including all noun-like elements, nominalized processes, and epithets, functioning similarly as nouns. Arnheim (1974, 1982) uses the term “volume”, but a volume, it seems,is more concerned with mediality rather than modality. It is not an apt term for describing the features of a sign.

As we discussed above, the multimodal nominal shares most of the features of the linguistic noun and nominal, but there are certain types of signs like icons and indexes that are weak in sharing certain features, such as the conventional or the non-natural medium. In this way, we can see that, instead of taking all the features as criteria for the determination of the nominal category, it is more desirable to take the essential features of the nominal as the main criteria, that is, conventional and non-natural mediums. Here,both the linguistic sign and the symbolic sign meet the criteria (except that some of the symbolic signs may be weak in the non-natural medium, as in the case of rose signifying the concept of love).

All signs are, in a sense, symbolic in nature, but some types of signs are very weak in this aspect, like icons, and others are weak in the non-natural medium, like indexes.In this sense, nominals are ranged from the most nominal, like the linguistic sign and the braille sign, to the least nominal, like the picture taken with a camera.

Figure 5. The continuum of nominalness of signs in different semiotic systems

When we recognize the status of the nominal in multi-semiotic systems, then we need to recognize the unit of the “clause” in multimodal grammar; as the nominal has to have a function in a multimodal clause, a unit larger than a group as the nominal represents both the word and the group in multimodal grammar. A multimodal clause may be linear or multi-dimensional.

However, whether it is the least nominal or the most nominal, when a sign functions as a participant in the transitivity structure of a multimodal clause, it will be recognized as a nominal as it becomes a nominalized element, whether it is a noun, or nominal, or not. In this sense, the functional status of the elements in the multimodal grammatical structure helps to reveal its class nature as a noun or nominal, and this is in line with the idea underlying functional grammar: the grammatical patterns are interpreted in terms of configurations of functions (Halliday, 1994, p. F36).

7. Conclusive Remarks

In order to base our study of multimodal grammar on solid ground, we need to develop a metalanguage for the class of elements in different semiotic systems, so it is necessary to recognize the noun, or noun-like category, in multimodal text analysis. We prefer to use the term ‘nominal’, rather than ‘noun’, as it is more general and abstract, and rather than ‘volume’ as it is concerned with multimodality, not multimediality. Along with that, we also need to employ another term, “the multimodal clause”, so that the category of nominal can be chosen from the system to function in a multimodal structure. The concept of the nominal here may have a set of features defining it, but the major ones are conventionality and the non-natural medium (especially conventionality).

The study is not just concerned with the proposal of the use of a particular concept,but also related to a new perspective for the study of semiotic systems and multimodal discourses. For example, should we describe the lexis or lexicogrammar of different semiotic systems? Should multimodal discourse or text be studied by relating functions to the classes of the system? In this sense, it carries with it a heavy load. Further study or consideration is necessary for the further development of multimodal discourse analysis.

Arnheim, R. (1974).Art and visual perception. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Arnheim, R. (1982).The power of the centre. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Grunske, L., Wenter, K.,, & Yatapanage, N. (2008). Defining the abstract syntax of visual languages with advanced graph grammars—A case study based on behavior trees.Journal of Visual Languages and Computing,19, 343-379.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1967).Grammar, society and the noun(lecture given at University College London on 24 November, 1966). London: Lewis & Co. Ltd. for University College London.Halliday, M. A. K. (1975).Learning how to mean: Explorations in the development of language.London: Edward Arnold.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1994).Introduction to functional grammar(2nd ed.). London: Edward Arnold.

Hjelmslev, L. (1943/1963).Prolegomena to a theory of language(Trans., F. Whitfield). Madison:University of Wisconsin Press.

Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (1996/2006).Reading images: The grammar of visual design.London: Routledge.

Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2002). Colour as a semiotic mode: Notes for a grammar of colour.Visual Communication,1(3), 343-368.

Lewis, C. T., & Short, C. (1879).A Latin dictionary.Medford and Somerville: The Perseus Project.

Liddell, H. G., & Scott, R. (1897).A Greek–English lexicon.Medford and Somerville: The Perseus Project.

Machin, D. (2007).Introduction to multimodal analysis. London: Hodder Arnold.

Pharies, C. S. (1985).Charles S. Peirce and the linguistic sign. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Saussure, F. de. (1915).Course in general linguistics. Paris: Payot.

Trescak, T., Esteva, M., & Rodriguez, T. (2012). A shape grammar interpreter for rectilinear forms.Computer-Aided Design,44, 657-670.

杂志排行

Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- The Logic of Legal Narrative1

- An Embodied View of Physical Signs in News Cartoons

- Complementiser and Complement Clause Preference for Verb-Heads in the Written English of Nigerian Undergraduates

- Towards a Semantic Explanation for the(Un)acceptability of (Apparent) Recursive Complex Noun Phrases and Corresponding Topical Structures

- Developing Mathematics Games in Anaang

- Identif i cation by Antithesis and Oppositional Discourse Reproduction in Chinese Space of New Media