重症儿童应激性溃疡预防的研究进展

2023-06-25克日曼·帕尔哈提穆热迪力·木合塔尔阿布来提·阿不都哈尔

克日曼·帕尔哈提 穆热迪力·木合塔尔 阿布来提·阿不都哈尔

【摘要】 应激性溃疡预防在重症患者中的应用十分普遍,但随着现代医疗水平的提高,与应激相关的消化道出血的发生率下降,且越来越多的研究开始关注预防药物的副作用和过度使用的现状,使得应激性溃疡预防药物的常规使用受到质疑。本文通过综述应激性溃疡的发病机制、危险因素和不同预防策略的优势及其弊端,旨在为应激性溃疡预防在重症患儿中的合理应用提供依据。

【关键词】 应激性溃疡 预防 重症监护

Research Advance of Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis in Critically Ill Children/PAERHATI Keriman, MUHETAER Muredili, ABUDUHAER Abulaiti. //Medical Innovation of China, 2023, 20(10): -188

[Abstract] Stress ulcer prophylaxis is widely used in critically ill patients, but with modern medical advances, the incidence of stress-related gastrointestinal bleeding has declined and a growing number of studies are focusing on the side effects and overuse of prophylactic drugs, which has brought into question the routine use of prophylactic drugs. This article reviews the pathogenesis, risk factors and benefits and drawbacks of different prevention strategies of stress ulcer, aiming to provide a basis for the rational application of stress ulcer prophylaxis in critically ill children.

[Key words] Stress ulcer Prophylaxis Intensive care

First-author's address: College of Pediatrics, Xinjiang Medical University, Urumqi 830000, China

doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-4985.2023.10.043

应激性溃疡是指机体在各种重大创伤、危重疾病、大型手术或严重心理疾病等应激状态下出现的消化道黏膜急性糜烂、溃疡等病变[1]。内镜检查显示75%~100%的危重症患者会在发病24~72 h出现应激相关胃肠道黏膜损伤[2],这种损伤可以发展为胃肠道溃疡、出血。但随着对血流动力学管理的改善及机械通气患者的精细护理,与应激相关消化道出血的发生率有所降低,目前在儿童重症监护室(pediatric intensive care unit,PICU)中的发生率为2%~5%[3]。因儿童正处于生长发育阶段,身体各项功能尚未发育完全,重症患儿若发生应激性溃疡出血或穿孔,可使病情恶化、原发疾病加重,甚至增加死亡率。因此在重症患儿的诊疗中,除积极治疗原发病外,应激性溃疡预防(stress ulcer prophylaxis,SUP)对改变预后非常重要。然而,近年来SUP药物导致的不良反应相关研究持续发表,使SUP在重症患者中常规使用的有效性及安全性颇受争议,为危重患儿进行合理的SUP已成为急需解决的问题。

1 发病机制

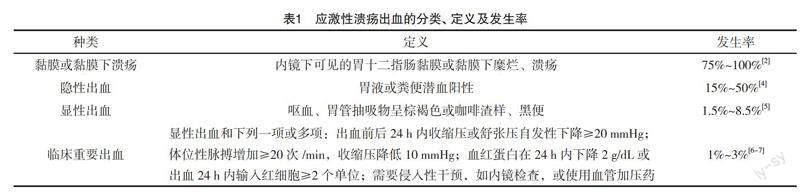

多种因素与应激性溃疡的发生有关,目前广为接受的观点为胃黏膜防御功能的减弱与相关损伤因子作用的增强。在重症患者中,由于低血容量、低心输出量或休克等引起的促炎癥状态、内脏低灌注和微循环受损可引起缺血再灌注损伤和胃内pH值降低,这些因素共同损害黏膜的完整性,随后可能会发生胃十二指肠的糜烂、溃疡和出血,其中出血相关定义及发生率见表1。而应激导致的迷走神经兴奋,通过使黏膜下动静脉短路开放,进一步加重黏膜的缺血缺氧。黏膜屏障的破坏可能比胃酸在发生胃肠道出血中的作用更为突出[4]。应激性溃疡中胃酸可能参与损伤,但低灌注和再灌注损伤为其主要机制,这正是消化性溃疡与应激性溃疡的不同之处。所以监测及维持血流动力学的稳定对于重症患者至关重要。

2 危险因素

研究显示,多种危险因素与重症患者发生应激性溃疡出血有关。一项多中心前瞻性研究表明,机械通气时间大于48 h和凝血功能障碍(血小板计数<50 000/mm3,国际标准化比值>1.5或活化部分凝血活酶时间>正常值的2倍)为应激性溃疡出血的独立危险因素。当这两项危险因素存在时,应激性溃疡出血的发生率为3.7%,而无危险因素的患者为0.1%[8]。儿童相关前瞻性研究显示呼吸衰竭、凝血功能障碍及儿童死亡风险评分≥10分为3项高危因素[9]。其他研究也得出了应激性溃疡出血的危险因素[10-11],包括严重颅脑、颈脊髓外伤、烧伤面积>30%、严重创伤、复杂手术、脓毒症、多脏器功能障碍综合征、休克、心肺脑复苏后、严重心理应激、使用大剂量糖皮质激素或合并使用非甾体类抗炎药、肾脏替代治疗和接受体外生命支持等。

3 药物预防

3.1 抑酸剂 胃酸、胃蛋白酶及各种损伤因子导致胃黏膜屏障破坏是使用抑酸剂的理论基础。抑酸剂主要为质子泵抑制剂(proton pump inhibitors,PPIs)和H2受体拮抗剂(histamine-2 receptor antagonists,H2RAs)。抑酸剂在PICU中的应用非常普遍,一项纳入333.6万名PICU患儿的研究发现,其中60.0%的患儿接受了抑酸治疗,70.4%单独使用H2RAs,17.8%单独使用PPIs,两种药物同时使用的患儿占11.8%[12]。成人相关研究表明,抑酸剂能显著减少胃肠道的出血[13-14],然而Abu El-Ella等[15]发表的随机对照试验发现,在PICU患者中使用PPIs进行SUP时,未能降低胃肠道出血的发生率。2021年发表的荟萃分析也得出同样的结论,即抑酸剂在减少重症患儿显性胃肠道出血方面无显著意义[3]。但因这项研究纳入了1986-2006年发表的试验,且样本量较少,存在一定局限性。其他方面,抑酸剂对于死亡率的影响目前仍存在争议[16-17],而无论是成人或儿童,使用抑酸剂都有引起感染的可能[15,18]。

PPIs有抑酸能力强、持续应用无耐药现象、肝内代谢,肾衰患者无需调整剂量等药理学优点,但与H2RAs相比易增加感染风险[19],这可能是在儿童中H2RAs较PPIs的使用率更高的原因之一[12,20]。目前比较PPIs和H2RAs在重症患儿SUP中作用的相关研究较少,期待未来有更多高质量的研究发表,为重症患儿SUP药物的选择提供依据。

3.2 抗酸剂及黏膜保护剂 常见的抗酸药物为碳酸氢钠、氢氧化铝、铝碳酸镁等,但因其副作用较多,一般不作为临床一线用药[21]。目前临床上最常用且最具成本效益的黏膜保护剂为硫糖铝,其通过与暴露蛋白质的静电结合黏附于胃黏膜受损区域,从而形成黏性覆层而起作用,但因其给药途径局限,评价硫糖铝在SUP中作用的研究较少。Thorburn等[22]的研究表明急性肾衰竭患儿,尤其是接受腹膜透析的患儿,在使用硫糖铝预防应激性溃疡时血液中铝浓度明显升高,而且血肌酐与铝浓度有相关性。故不建议在PICU中将硫糖铝作为SUP药物,若需使用时,应监测铝浓度。

3.3 用药方式及时机 国内外相关研究已指出胃肠道出血高风险的患者需进行SUP,但对预防药物开始使用的时间、种类、方法及停药标准等均不明确。目前国内外暂无针对儿童患者的SUP指南发表,已发表的PPIs相关指南表明,PPIs可适用于有凝血障碍伴应激相关胃肠道出血风险的患儿,建议剂量为每日1 mg/kg(最高可达20 mg/d),在早上进食前服用[23]。随着对重症儿童SUP药物的不断研究及临床试验的不断更新,期待相关指南早日颁布。

4 药物弊端

4.1 肺炎 胃酸通过防止细菌定植而对机体起防御作用,抑制胃酸可能导致细菌过度繁殖,胃排空时间延长,细菌易位及正常肠道菌群改变[24],而抑酸剂的使用可能还与中性粒细胞功能受损有关[25-26]。

医院获得性肺炎(hospital acquired pneumonia,HAP)的发生受多种因素影响,如不同医疗机构的细菌谱、护理水平、医生的医疗习惯等,但目前有研究提示抑酸剂增加HAP发生的风险不容忽视。一项大型队列研究发现,预防性使用PPIs组HAP的发生率高于未使用PPIs组,且随着PPIs剂量的增加,发生HAP的风险增加[27]。然而针对PICU患者的随机对照试验提示,接受PPIs和不接受预防性用药的患儿相比,在HAP的发生率上无显著差异[15],这与2022的发表的一项荟萃分析结果一致,即抑酸治疗不是HAP发生的危险因素[28]。

虽然抑酸剂与HAP之间的关系尚不明确,但是呼吸道作为重症患儿最常见且最重要的感染部位,不应忽视抑酸剂可能带来的潜在感染风险。为进一步明确抑酸剂与HAP之间的关系,需在PICU中进一步开展高质量的临床研究。

4.2 艰难梭菌感染 艰难梭菌是一种专性厌氧、革兰阳性梭状产毒芽孢杆菌,可引起艰难梭菌感染(clostridium difficile infection,CDI)。轻者引起腹泻,重者可出现伪膜性肠炎、中毒性巨结肠、结肠穿孔等,甚至可造成死亡。目前我国住院腹泻患者CDI发生率高达19%[29],ICU患者CDI患病率明显高于普通病房患者,发生CDI的ICU患者死亡率增加、住院时间延长[30]。既往研究认为抗生素的使用为CDI的重要原因,而越来越多的研究证实抑酸剂的使用亦为其重要原因之一[31-33],且与H2RAs相比,使用PPIs进行SUP时,CDI发生风险增加38.6%[34]。CDI在成人中比儿童更常见,然而有研究显示,住院儿童CDI的发生率正在上升,且PICU和血液/肿瘤病房住院是CDI的独立危险因素[35]。故对于使用抑酸剂且怀疑有CDI的重症患儿应加强感染监测,并早期制订感染控制方案。

4.3 其他弊端 抑酸剂的过度使用十分普遍,且处方金额巨大。90%的ICU患者接受了应激性溃疡的预防性治疗[36],2017年PPIs国内销售额为188亿,自2017年起,多省市将PPIs列为重点监控药物品种[37]。抑酸剂的不合理使用可能造成各器官系统的不良反应,近年来在儿童患者中一些潜在不良反应如骨折、肾脏损伤、抑郁和焦虑、坏死性小肠结肠炎、过敏性疾病和肥胖、低镁血症、维生素B12缺乏、血小板减少症等备受关注[38-45]。

5 肠内营养(enteral nutrition,EN)

药物预防一直是SUP的主要选择,但最近的临床研究试图评估EN在SUP中的作用。EN通过维持胃肠道屏障功能,为黏膜细胞提供能量,从调节免疫及增强胃肠道运动等方面保护胃肠道,从而预防应激性溃疡出血[46]。Huang等[36]在基于7项随机对照试验的荟萃分析中发现,在接受EN的重症患者中,SUP药物的使用与否对胃肠道出血率、总死亡率、艰难梭菌感染、机械通气时间和ICU住院时长没有显著影响。两项最近发表的回顾性研究也得出类似的结果,即在接受EN的重症患者中,药物预防不会降低胃肠道出血发生率[47-48]。

目前尚无将EN作为SUP唯一手段的前瞻性随机对照试验数据,且EN在危重儿童SUP中的研究较少,若未来有相关研究发表,建议详细阐述EN开始及持续时间,具体剂量及所提供热量等,为EN更加精细化的应用提供依据。

6 其他治疗

心理预防及镇静镇痛为重症患者SUP的重要方面。因病情及陌生环境,重症患儿有恐惧、紧张不安等心理,甚至可能出现分离性焦虑等。一项纳入8~17 岁PICU住院患儿的研究显示,住院期间急性应激发生率高,几乎所有患儿(96%)都有创伤后应激,74.8%的患儿有急性应激症状,6%符合急性应激障碍诊断标准[49]。因PICU患兒年龄跨度大、身心状态不同、病情严重程度不一,为减少应激性溃疡的发生,需制定个性化的心理指导及护理干预,同时也要注意镇静镇痛的评估及合理应用。

7 總结

综上所述,SUP在重症患儿中的应用广泛,然而其收益及风险仍存在争议。重症医师在识别高危患儿的同时,应积极处理原发病及危险因素,尽可能消除应激源。在药物预防方面,因儿童相关研究较少,现无明确证据指导最佳药物的选择。但重症医师需明确,用药应仅限于有高危因素的危重症患儿,为减少药物副作用,对无指征的患者应避免使用预防药物。危重患儿的SUP药物与安慰剂比较的随机对照试验正在进行[50],期待未来有更多相关高质量研究的发表,为重症患儿SUP药物的选择提供依据。在EN方面,近几年的研究不断证实其在预防应激性溃疡出血中起保护作用,相关指南也提出当重症患者恢复进食后,应停用SUP药物,且早期EN可能是药物预防应激性溃疡的可行替代方案[51]。建议临床实践中对无EN禁忌的危重症患儿行早期EN,并做好胃肠功能监护。

因儿童这一群体的特殊性,不同年龄、不同性别、不同疾病状态等情况下,对其进行SUP时需反复评估、权衡利弊,使用预防性药物时,需做到精准,并综合考虑其安全性及有效性,使用过程中应监测可能出现的不良反应。期待未来有更多相关高质量研究的发表,为临床决策及制订更加安全有效SUP方案提供循证医学依据。

参考文献

[1]柏愚,李延青,任旭,等.应激性溃疡防治专家建议(2018版)[J].中华医学杂志,2018,98(42):3392-3395.

[2] ALHAZZANI W,ALSHAHRANI M,MOAYYEDI P,et al.

Stress ulcer prophylaxis in critically ill patients: review of the evidence[J].Pol Arch Med Wewn,2012,122(3):107-114.

[3] JENSEN M M,MARKER S,DO H Q,et al.Prophylactic acid suppressants in children in the intensive care unit: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis[J].Acta Anaesthesiol Scand,2021,65(3):292-301.

[4] COOK D,GUYATT G.Prophylaxis against upper gastrointestinal bleeding in hospitalized patients[J].N Engl J Med,2018,378(26):2506-2516.

[5] FINKENSTEDT A,BERGER M M,JOANNIDIS M.Stress ulcer prophylaxis: Is mortality a useful endpoint?[J].Intensive Care Med,2020,46(11):2058-2060.

[6] SAEED M,BASS S,CHAISSON N F.Which ICU patients need stress ulcer prophylaxis?[J].Cleve Clin J Med,2022,89(7):363-367.

[7] KRAG M,PERNER A,WETTERSLEV J,et al.Prevalence and outcome of gastrointestinal bleeding and use of acid suppressants in acutely ill adult intensive care patients[J].Intensive Care Med,2015,41(5):833-845.

[8] COOK D J,FULLER H D,GUYATT G H,et al.Risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients. Canadian Critical Care Trials Group[J].N Engl J Med,1994,330(6):377-381.

[9] CHAIBOU M,TUCCI M,DUGAS M A,et al.Clinically significant upper gastrointestinal bleeding acquired in a pediatric intensive care unit: a prospective study[J].Pediatrics,1998,102(4 Pt 1):933-938.

[10] QUENOT J P,THIERY N,BARBAR S.When should stress ulcer prophylaxis be used in the ICU?[J].Curr Opin Crit Care,2009,15(2):139-143.

[11] MAZZEFFI M,KIEFER J,GREENWOOD J,et al.Epidemiology of gastrointestinal bleeding in adult patients on extracorporeal life support[J].Intensive Care Med,2015,41(11):2015.

[12] COSTARINO A T,DAI D,FENG R,et al.Gastric acid suppressant prophylaxis in Pediatric Intensive Care: current practice as reflected in a large administrative database[J].Pediatr Crit Care Med,2015,16(7):605-612.

[13] KRAG M,MARKER S,PERNER A,et al.Pantoprazole in patients at risk for gastrointestinal bleeding in the ICU[J].N Engl J Med,2018,379(23):2199-2208.

[14] WANG Y,YE Z,GE L,et al.Efficacy and safety of gastrointestinal bleeding prophylaxis in critically ill patients: systematic review and network meta-analysis[J].BMJ,2020,368:l6744.

[15] ABU EL-ELLA S S,SAID EL-MEKKAWY M,MOHAMED SELIM A.Stress ulcer prophylaxis for critically ill children: routine use needs to be re-examined[J].An Pediatr (Engl Ed),2021,96(5):402-409.

[16] YOUNG P J,BAGSHAW S M,FORBES A B,et al.Effect of stress ulcer prophylaxis with proton pump inhibitors vs histamine-2 receptor blockers on in-hospital mortality among ICU patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation: the PEPTIC randomized clinical trial[J].Jama,2020,323(7):616-626.

[17] LEE T C,GOODWIN W M,LAWANDI A,et al.Proton pump inhibitors versus histamine-2 receptor antagonists likely increase mortality in critical care: an updated Meta-analysis[J/OL].Am J Med,2021,134(3):e184-e188.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32931766/.

[18] ALHAZZANI W,ALSHAMSI F,BELLEY-COTE E,et al.

Efficacy and safety of stress ulcer prophylaxis in critically ill patients: a network meta-analysis of randomized trials[J].Intensive Care Med,2018,44(1):1-11.

[19] MACLAREN R,REYNOLDS P M,ALLEN R R.Histamine-2 receptor antagonists vs proton pump inhibitors on gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage and infectious complications in the intensive care unit[J].JAMA Intern Med,2014,174(4):564-574.

[20] DUFFETT M,CHAN A,CLOSS J,et al.Stress ulcer prophylaxis in critically ill children: a multicenter observational study[J/OL].Pediatr Crit Care Med,2020,21(2):e107-e113.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31821206/.

[21]中華医学会创伤学分会神经损伤专业组,中华医学会神经外科学分会颅脑创伤专业组.颅脑创伤后应激性溃疡防治中国专家共识[J].中华神经外科杂志,2018,34(7):649-652.

[22] THORBURN K,SAMUEL M,SMITH E A,et al.Aluminum accumulation in critically ill children on sucralfate therapy[J].Pediatr Crit Care Med,2001,2(3):247-249.

[23] JORET-DESCOUT P,DAUGER S,BELLAICHE M,et al.

Guidelines for proton pump inhibitor prescriptions in paediatric intensive care unit[J].Int J Clin Pharm,2017,39(1):181-186.

[24] BAVISHI C,DUPONT H L.Systematic review: the use of proton pump inhibitors and increased susceptibility to enteric infection[J].Aliment Pharmacol Ther,2011,34(11-12):1269-1281.

[25] ZEDTWITZ-LIEBENSTEIN K,WENISCH C,PATRUTA S,et al.Omeprazole treatment diminishes intra- and extracellular neutrophil reactive oxygen production and bactericidal activity[J].Crit Care Med,2002,30(5):1118-1122.

[26] OZATIK O,OZATIK F Y,TEKSEN Y,et al.Research into the effect of proton pump inhibitors on lungs and leukocytes[J].Turk J Gastroenterol,2021,32(12):1003-1011.

[27] MAO X,YANG Z.Association between hospital-acquired pneumonia and proton pump inhibitor prophylaxis in patients treated with glucocorticoids: a retrospective cohort study based on 307,622 admissions in China[J].J Thorac Dis,2022,14(6):2022-2033.

[28] LUKASEWICZ FERREIRA S A,HUBNER DALMORA C, ANZILIERO F,et al.Factors predicting non-ventilated hospital-acquired pneumonia: systematic review and meta-analysis[J].

J Hosp Infect,2022,119:64-76.

[29]谢和宾,曾鸿,尹柯,等.我国住院腹泻患者艰难梭菌感染率的荟萃分析[J].中华医院感染学杂志,2017,27(5):961-964.

[30] CAMPBELL C T,POISSON M O,HAND E O.An updated review of Clostridium difficile treatment in pediatrics[J].J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther,2019,24(2):90-98.

[31] TRIFAN A,STANCIU C,GIRLEANU I,et al.Proton pump inhibitors therapy and risk of Clostridium difficile infection: systematic review and meta-analysis[J].World J Gastroenterol,2017,23(35):6500-6515.

[32] CAO F,CHEN C X,WANG M,et al.Updated meta-analysis of controlled observational studies: proton-pump inhibitors and risk of Clostridium difficile infection[J].J Hosp Infect,2018,98(1):4-13.

[33] BARLETTA J F,SCLAR D A.Proton pump inhibitors increase the risk for hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infection in critically ill patients[J].Crit Care,2014,18(6):714.

[34] AZAB M,DOO L,DOO D H,et al.Comparison of the hospital-acquired clostridium difficile infection risk of using proton pump inhibitors versus histamine-2 receptor antagonists for prophylaxis and treatment of stress ulcers: a systematic review and Meta-analysis[J].Gut Liver,2017,11(6):781-788.

[35] KARAASLAN A,SOYSAL A,YAKUT N,et al.Hospital acquired Clostridium difficile infection in pediatric wards: a retrospective case-control study[J].Springerplus,2016,5(1):1329.

[36] HUANG H B,JIANG W,WANG C Y,et al.Stress ulcer prophylaxis in intensive care unit patients receiving enteral nutrition: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J].Crit Care,2018,22(1):20.

[37]王佳,李丹瀅,葛卫红.注射用质子泵抑制剂预防应激性溃疡的应用现状与挑战[J].药学与临床研究,2020,28(6):451-454,458.

[38] WANG Y H,WINTZELL V,LUDVIGSSON J F,et al.

Association between proton pump inhibitor use and risk of fracture in Children[J].JAMA Pediatr,2020,174(6):543-551.

[39] WANG Y H,WINTZELL V,LUDVIGSSON J F,et al.Proton pump inhibitor use and risk of depression and anxiety in children: nationwide cohort study[J].Clin Transl Sci,2022,15(5):1112-1122.

[40] LI Y,XIONG M,YANG M,et al.Proton pump inhibitors and the risk of hospital-acquired acute kidney injury in children[J].Ann Transl Med,2020,8(21):1438.

[41] ZVIZDIC Z,MILISIC E,JONUZI A,et al.The Effects of Ranitidine treatment on the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants: a case-control study[J].Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove),2021,64(1):8-14.

[42] MITRE E,SUSI A,KROPP L E,et al.Association between use of acid-suppressive medications and antibiotics during infancy and allergic diseases in early childhood[J/OL].JAMA Pediatr,2018,172(6):e180315.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29610864/.

[43] STARK C M,SUSI A,EMERICK J,et al.Antibiotic and acid-suppression medications during early childhood are associated with obesity[J].Gut,2019,68(1):62-69.

[44] NEHRA A K,ALEXANDER J A,LOFTUS C G,et al.Proton pump inhibitors: review of emerging concerns[J].Mayo Clin Proc,2018,93(2):240-246.

[45] PHAN A T,TSENG A W,CHOUDHERY M W,et al.Pantoprazole-

associated thrombocytopenia: a literature review and case report[J/OL].Cureus,2022,14(2):e22326.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35371663/.

[46] SCHORGHUBER M,FRUHWALD S.Effects of enteral nutrition on gastrointestinal function in patients who are critically ill[J].Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol,2018,3(4):281-287.

[47] HAMILTON L A,DARBY S H,ROWE A S.A retrospective cohort analysis of the use of enteral nutrition plus pharmacologic prophylaxis or enteral nutrition alone[J].Hosp Pharm,2021,56(6):729-736.

[48] OHBE H,MORITA K,MATSUI H,et al.Stress ulcer prophylaxis plus enteral nutrition versus enteral nutrition alone in critically ill patients at risk for gastrointestinal bleeding: a propensity-matched analysis[J].Intensive Care Med,2020,46(10):1948-1949.

[49] NELSON L P,LACHMAN S E,GOODMAN K,et al.Admission psychosocial characteristics of critically ill children and acute stress[J].Pediatr Crit Care Med,2021,22(2):194-203.

[50] MILLS K I,ALBERT B D,BECHARD L J,et al.Stress ulcer prophylaxis versus placebo-a blinded randomized control trial to evaluate the safety of two strategies in critically ill infants with congenital heart disease (SUPPRESS-CHD)[J].Trials,2020,21(1):590.

[51] WEISS S L,PETERS M J,ALHAZZANI W,et al.Surviving sepsis campaign international guidelines for the management of septic shock and sepsis-associated organ dysfunction in children[J/OL].Pediatr Crit Care Med,2020,21(2):e52-e106.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32030529/.

(收稿日期:2023-02-21) (本文編辑:张明澜)