重症病毒性脑炎患儿非惊厥性癫持续状态9例临床分析

2015-04-22陈文雄杨思达高媛媛周艳霞刘鸿圣彭炳蔚王秀英麦坚凝陶建平宁书尧钟燕银

陈文雄 杨思达 高媛媛 周艳霞 刘鸿圣 彭炳蔚 王秀英 麦坚凝 陶建平 宁书尧 钟燕银

·论著·

陈文雄1杨思达1高媛媛1周艳霞1刘鸿圣2彭炳蔚1王秀英1麦坚凝1陶建平3宁书尧1钟燕银1

1 方法

1.1 重症病毒性脑炎诊断标准 参照《诸福棠实用儿科学》儿童病毒性脑炎诊断标准[6],符合以下条件之一为重症病毒性脑炎[7]:①频繁抽搐或惊厥持续状态;②稽留高热;③不同程度意识障碍;④脑干颅神经损害;⑤颅内高压症、脑疝形成;⑥多脏器功能衰竭。

1.3 研究对象纳入标准 检索我院神经内科2012年6月至2014年9月电子病案系统,符合重症病毒性脑炎和NCSE诊断的病例进入本文分析。

1.4 VEEG监测方法 我院VEEG监测采用美国Nicolet公司Nicolet-one 32通道视频脑电图仪,按照国际10-20系统标准安放19个头皮记录电极,记录患儿发作期及发作间期VEEG;昏迷患儿持续或间断密集VEEG监测7 d,之后1~2周定期复查VEEG;非昏迷患儿均行至少1次VEEG监测,连续记录最少1 h,1~2周定期复查VEEG;结果由神经内科及脑电图医生结合脑电记录分析,按统一标准判定;监测过程中予地西泮0.3 mg·kg-1静脉注射,每次最大剂量<10 mg,以1~2 mg·min-1均匀注入。节律性异常脑电波减少或消失,同时伴临床征象好转为药物起效的标准。

表1 NCSE的临床标准[9]

注 以上标准改良自Kaplan(2007)[12]。1)样放电:棘波,多棘波,尖波、尖慢综合波;2)若EEG改善而临床表现无改善,或波动无确定演化,应考虑NCSE可能;3)具发作频率、波幅及分布的演化现象:起始递增(波幅增加与频率改变),或模式演化(频率改变>1 Hz或分布改变),或终末递减(波幅或频率)。

2 结果

2.1 一般资料 9例重症病毒性脑炎NCSE连续病例进入本文分析,男5例,女4例。脑炎起病年龄(7.2±3.9)岁,入院时Glasgow评分(8.6±1.9)分,脑炎起始与NCSE起始间隔4~70(19.4±20.9)d。

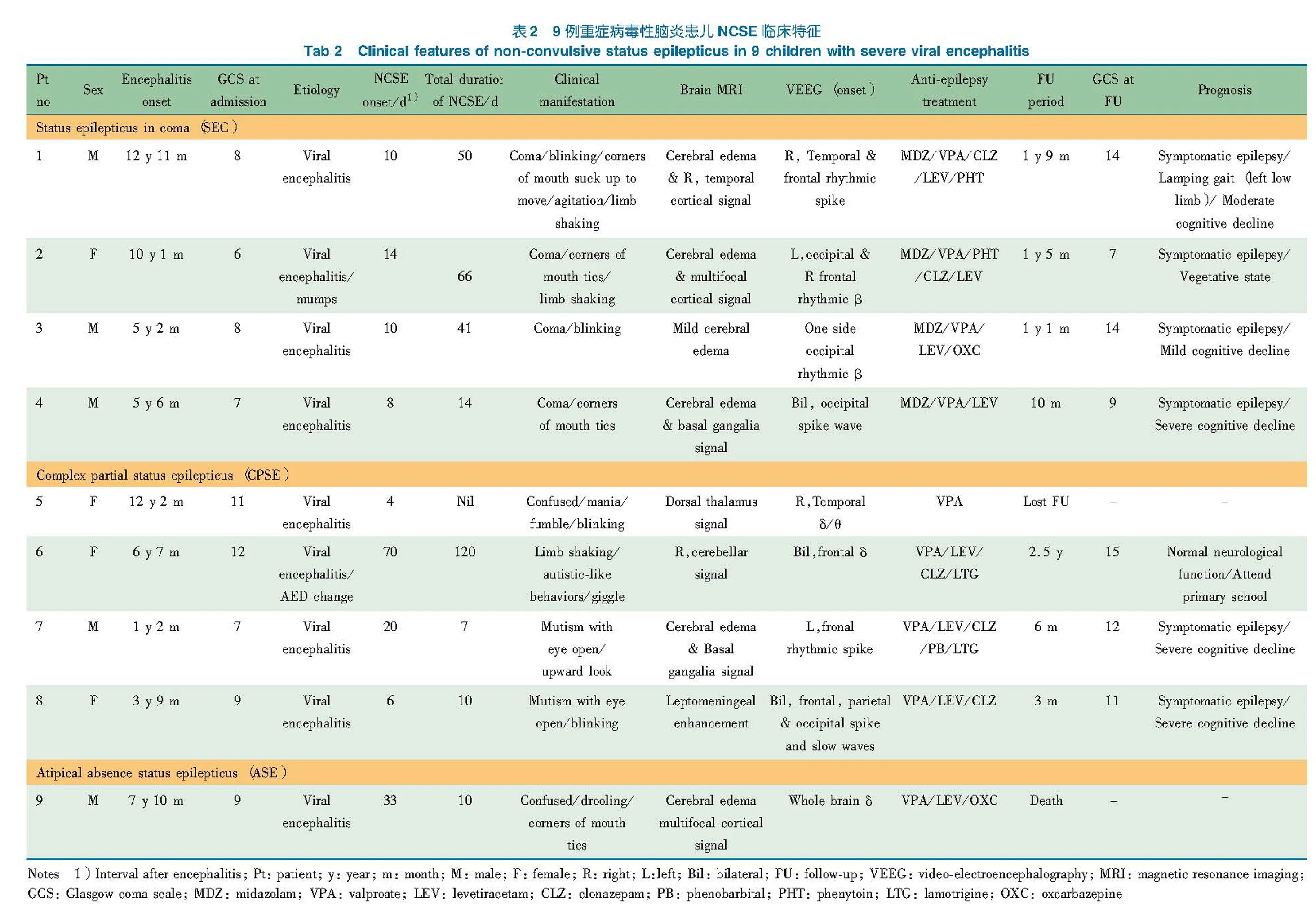

2.2 临床特征(表2)

2.2.1 病因分析 9例CSF病原学(单纯疱疹病毒、巨细胞病毒、肺炎支原体、肠道病毒、EB病毒)检测未发现明确病原,其中例2感染腮腺炎,例6合并惊厥,在调整AEDs期间出现NCSE。

2.2.2 NCSE类型 SEC 4例(例1~4),CPSE 4例(例5~8),不典型ASE 1例(例9)。

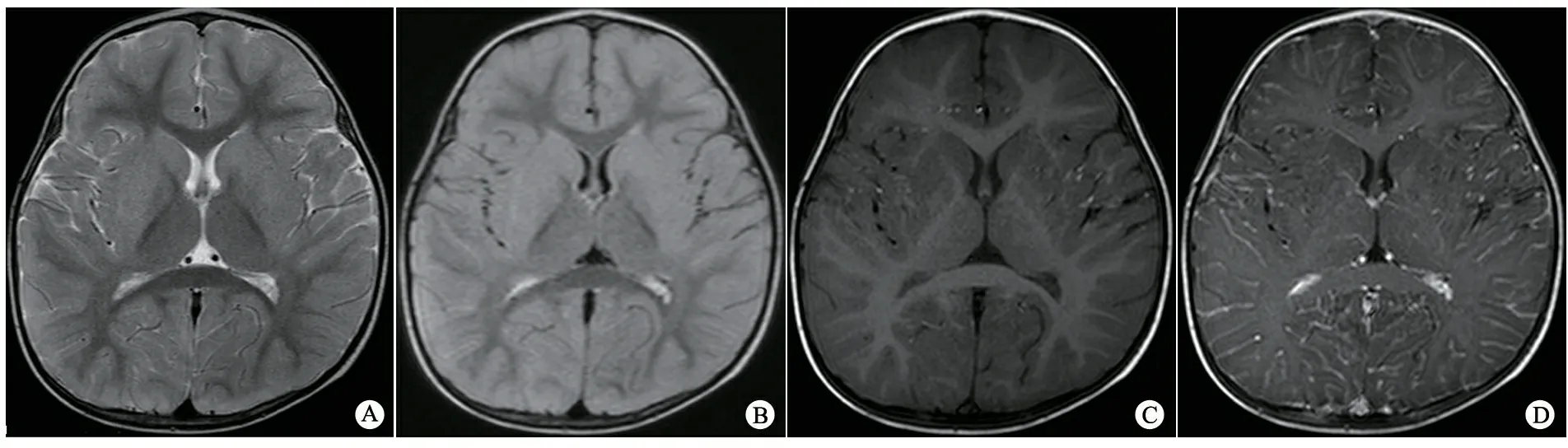

图1 例7EEG表现

Fig 1 EEG findings of case 7

Notes Male, 1 y 2 m. A: eyes-open state of mutism with upward look of both eyes; recording parameters: bilateral ear referential montage, paper speed 3 cm·s-1, high frequency 70 Hz, low frequency 0.5 Hz; ictal VEEG: background electrical activity slow, spike rhythm at left frontal pole & frontal area; B: the behaviors of cry with upward look of both eyes were reduced after 2 min of intravenous administration of diazepam; recording parameters: bilateral ear referencial montage, paper speed 3 cm·s-1, high frequency 70 Hz, low frequency 0.5 Hz; VEEG after 2.2 min of intravenous administration of diazepam: the fast wave at frontal area disappeared with the background of 2-3 Hz moderate low amplitude delta rhythm

2.4 临床发现 4例SEC患儿临床发现包括昏迷、昏睡、躁动、肢体或嘴角微小抽动、轻微眨眼或眼震和嘴角咂动等;4例CPSE患儿临床发现包括认知倒退、不能认人、不清醒、混乱、躁狂、眨眼、嘴角轻微抽动、睁眼缄默、斜视和手摸索等,其中例6在AEDs减量调整过程中出现孤独症样行为(叫名不理、眼神回避、刻板样重复行为等);例9不典型ASE患儿表现为不清醒、混乱、嘴角轻微抽动及流涎。

2.5 MRI 9例病毒性脑炎急性期均行头颅MRI检查,均有不同程度异常发现,以脑实质或脑膜局灶、多局灶、弥漫性损害为特点(图2)。6例患儿双侧大脑皮质弥漫性肿胀并异常信号(2例累及基底节),例6累及小脑,例5累及背侧丘脑,例8累及软脑膜(表 2)。

图2 例7MRI所见

Fig 2 Cerebral MRI findings of case 7

Notes Case 7, male, 1 y 2 m. A: Brain MRI (acute phase): Bilateral cerebral hemisphere and basal ganglia swellen; T2WI and T2WI FLAIR: signal diffuse increased slightly; T1WI signal did not change significantly; Contrast-enhanced scan: The shadow of enhanced small blood vessels on the surface of bilateral cerebral hemisphere increased

2.6 治疗、预后与随访 4例SEC患儿予咪达唑仑联合多种AEDs(丙戊酸钠、左乙拉西坦、苯妥英钠、氯硝西泮)治疗;4例CPSE和1例不典型ASE患儿予丙戊酸钠、左乙拉西坦和氯硝西泮等治疗。例5自动出院,余8例NCSE持续(39.8±39.2)d,其中4例SEC患儿NCSE持续(42.8±21.8)d;3例非SEC患儿(例7~9)NCSE持续(9.0±1.7)d,例6 NCSE持续4个月。

3例复查MRI提示遗留轻度异常:双侧大脑半球脑沟加深,幕上脑室稍丰满(例1、3)、双侧小脑半球脑沟稍加深(例6);例2和4遗留弥漫性慢性缺损;例7和8提示亚急性局灶缺损。

3 讨论

本文9例前驱均有惊厥发作。Tay等[14]报道12/19例患儿存在前驱惊厥发作。晚近有研究[7]报道前驱惊厥发作可增加34%发生NCSE的可能;本文3例前驱尚有CSE发生。Tay等[14]也报道5/19例患儿前驱发生CSE。张赟健等[17]报道2例NCSE患儿前驱有CSE发生。汪叶松等[17]监测17例CSE发作后成人患者,4例诊断为NCSE。Feen等[18]建议CSE发作停止后伴意识改变>20 min者,均需行VEEG监测。

3.2 重症病毒性脑炎患儿NCSE的临床发现 Kaplan等[19]将非惊厥发作临床表现归纳为兴奋性与抑制性症状。本文发现重症病毒性脑炎患儿非惊厥发作既有兴奋性,亦有抑制性症状,表现多样,包括昏迷、躁动、眨眼或眼震、肢体或口面部微小抽动、认知障碍、孤独症样行为、自动症及睁眼缄默等。汪叶松等[17]及申浩等[20]也报道重症或昏迷成人患者NCSE临床表现存在口、眼或肢体微小抽动,混乱、谵妄等精神症状,或仅有昏睡状态。新近的NCSE临床标准[9]提示,觉察临床细微的发作现象,如眨眼、肢体或口面部的微小抽动等,也是支持NCSE诊断的依据之一。

3.3 重症病毒性脑炎患儿NCSE的MRI表现 本文9例病毒性脑炎急性期均有不同程度头颅MRI异常发现,以双侧大脑皮质广泛性损害为主,可能直接或间接与EEG异常放电的起源部位相关,提示头颅神经影像学脑炎急性期异常可能是NCSE发生的潜在危险因素。Greiner等[7]报道急性皮质神经影像学异常增加了29%发生NCSE的可能,如惊厥与急性皮质神经影像学异常同时出现,则发生NCSE的可能性增至82%。

本文发现重症病毒性脑炎患儿初始Glasgow评分、MRI累及范围与预后可能相关。例2、4和9 Glasgow评分低,头颅MRI显示广泛性损害,预后较差;例1、3和6 Glasgow评分高,头颅MRI轻度异常的患儿预后相对较好。

NCSE对神经系统的影响尚不明确[5]。新近研究报道NCSE是创伤后大脑损伤患者脑萎缩的一个独立危险因素[28]。NCSE患儿死亡与潜在的惊厥原因相关,而非NCSE持续时间或是否出现NCSE[5]。当前证据表明临床症状改善至少在一定程度上与及时、有效的抗惊厥治疗相关[29]。因此,关注重症颅内感染患儿原发病治疗同时,不能忽视NCSE治疗。

本文的不足之处和局限性:①病毒性脑炎患儿多存在认知障碍伴不自主动作,较难与NCSE发作相鉴别,NCSE的实际病程可能更长; ②每1~2周随访EEG,可能影响对NCSE病例评估的准确性。

[1]Meierkord H,Holtkamp M. Non-convulsive status epilepticus in adults: clinical forms and treatment. Lancet Neurol, 2007, 6(4):329-339

[2]Shneker BF, Fountain NB. Assessment of acute morbidity and mortality in nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Neurology, 2003, 61(8):1066-1073

[3]Pisani F, Sisti L, Seri S. A scoring system for early prognostic assessment after neonatal seizures. Pediatrics, 2009,124(4):e580-587

[4]Galimi R. Nonconvulsive status epileptieas in pediatric populations: diagnosis and management.Minerva Pediatr,2012,64(3):347-355

[5]Greiner HM, Holland K, Leach JL, et al. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus: the encephalopathic pediatric patient. Pediatrics, 2012, 129:e748

[6]胡亚美,江载芳,主编.诸福棠实用儿科学.第7版.北京:人民卫生出版社,2002:759-763[7]Wu BM(吴保敏),Wang H, Ye LM,et al.The Diagnosis and treatment of children with viral encephalitis. Chinese Journal of practical Pediatrics (中国实用儿科杂志),2004,19(7):385-402

[8]Kaplan PW.The clinical features,diagnosis,and prognosis of nonconvulsive status epilepticus.Neurologist,2005,11(6):348-361

[9]Beniczky S, Hirsch LJ, Kaplan PW, et al. Unified EEG terminology and criteria for nonconvulsive status epileticus. Epilepsia, 2013, 54(S6):28-29

[10]The EEG & Epilepsy Expert group of Neurological society of Chinese Medial Association(中华医学会神经病学分会脑电图与癫痫学组). Expert consensus of the treatment of non-convulsive status epilepticus. Chin J Neurol(中华神经科杂志), 2013, 46(2): 133-137

[11]Maganti R, Gerber P, Drees C, et al. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Epilepsy Behav, 2008, 12(4):572-586

[12]Kaplan PW. EEG criteria for nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Epilepsia, 2007,48(S8):39-41

[13]Korff CM, Nordli Jr DR. Diagnosis and management of nonconvulsive status epilepticus in children. Nat Clin Pract Neurol, 2007, 3(9):505-516

[14]Tay SKH,Hirsch LJ,Leary L,et al. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus in children: Clinical and EEG characteristics. Epilepsia, 2006, 47(9):1504-1509

[15]Li H(李花), Hu XS, Fei LX, et al. The clinical features and EEG findings of nonconvulsive status epilepticus: 4 cases. Journal of Brain and Nervous Diseases(脑与神经疾病杂志), 2013, 21(3):161-164

[16]Zhang YJ(张赟健),Qiu PL,Zhou SZ,et al. Video-electroencephalogram momtoring in children with nonconvuisive status epilepticus. Chin J Appl Clin Pediatr (中华实用儿科临床杂志),2013,28(9):708-710

[17]Wang YS (汪叶松), Li YY,Cui W, et al. Analysis of non-convulsive status epilepticus in Neurological Intensive Care Unit. Chin J Emerg Med, 2011,20(10):1097-1099

[18]Feen ES,Bershad EM,Suarez JI. Status epileptus. South Med J, 2008,101(4):400-406

[19]Kaplan PW. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus in the emergency room. Epilepsia, 1996, 37(7):643-650

[20]Shen H(申浩),Chang L,Guang J,et al. Clinical features of nonconvulsive smtus epilepticus in comatose patients. J Clin Neurol(临床神经病学杂志), 2013, 26(3):228-230

[21]Abend NS, Dlugos DJ, Hahn CD, et al. Use of EEG monitoring and management of non-convulsive seizures in critically ill patients: a survey of neurologists. Neurocrit Care, 2010, 12(3):382-389

[22]Bonati LH, Naegelin Y, Wieser HG, et al. Beta activity in status epilepticus. Epilepsia, 2006, 47(1):207-210

[23]Zhang YJ(张赟健),Wang Y,Sun DK. Research progress in critically children with nonconvuisive status epilepticus. Chin J Pediatr (中华儿科杂志), 2011,49(2):128-131

[24]Mnatsakanyan L,Chung JM,Tsimefinov EI,et al.Intravenous Laco-samide in refractory nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Seizure,2012,21(3):198-201

[25]Metague A,Kneen R,Kumar R,et al.Intravenous levetiracetam in acute repetitive seizures and status epilepticus in children:experience from a children′s hospital.Seizure,2012,21(7):529-534

[26]Fernandez-Torre JL, kaplan PW, Rebollo M, et al. Ambulatory non-convulsive status epilepticus evolving into a malignant form. Epileptic Disord, 2012, 14(1):41-50

[27]Hopp JL,Sanchez A,Krumholz A,et al.Nonconvulsive status epilepticus:value of a benzodiazepine trial for predicting outcomes.Neurologist,2011,17(6):325-329

[28]Verpa PM, McArthur DL, Xu Y, et al. Nonconvulsive seizures after traumatic brain injury are associated with hippocampal atrophy. Neurology, 2010,75(9):792-798

[29]Arzimanoglou A. Outcome of status epilepticus in children. Epilepsia, 2007, 48(S8):91-93

(本文编辑:丁俊杰)

Analysis of non-convulsive status epilepticus in 9 children with severe viral encephalitis

CHENWen-xiong1,YANGSi-da1,GAOYuan-yuan1,ZHOUYan-xia1,LIUHong-sheng2,PENGBing-wei1,WANGXiu-ying1,MAIJian-ning1,TAOJian-ping3,NINGShu-yao1,ZHONGYan-yin1

(1DepartmentofNeurology;2DepartmentofMagneticResonance;3DepartmentofPediatricIntensiveCareUnit,GuangzhouWomenandChildren′sMedicalCenter,Guangzhou510623,China)

CHEN Wen-xiong,E-mail:chenwx100@hotmail.com

ObjectiveTo explore the clinical features, diagnosis and treatment of non-convulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) in children with severe viral encephalitis.MethodsThe clinical manifestations, video electroencephalographic (VEEG) features, anti-epilepsy treatment and prognosis of NCSE in children with severe viral encephalitis in the child neurological inpatient setting of Guangzhou Women and Children′s Medical Center between June 2012 and September 2014 were retrospectively analyzed. Results Nine patients including 5 boys were identified. The age onset of encephalitis was (7.2±3.9) years. The Glasgow scores of 9 patients were (8.6±1.9) points. The average interval between the onset of encephalitis and NCSE ranged from 4 to 70 (19.4±20.9) days. NCSE types included status epilepticus in coma (SEC) (n=4), complex partial status epilepticus (n=4), and atypical absence status epilepticus (n=1). Eight children were with severe viral encephalitis and 1 child with severe viral encephalitis in changing antiepileptic drug regimen. The preceding seizures in all children and convulsive status epilepticus in 3 patients were found. A variety of clinical manifestations, including limb or mouth and face tiny tic, eye blinking or nystagmus, cognitive impairment, autistic-like behavior, mutism with eye open and automatism were observed. The characteristics of ictal VEEG generally included slow activity of background; focal, multi-focal, or generalized δ, θ , β,spike rhythmic activity, or continuous spike and wave discharges; with the evolution of frequency, amplitude, and distribution; frequently of frontal or occipital lobe origin. The patients diagnosed as SEC were treated with general anesthesia (midazolam) plus multiple antiepileptic drug (AEDs) with average duration of attack of 42.8 days, whereas others with non-SEC were provided with multiple AEDs with average duration of attack of 9 days in 3 cases and 4 months in 1 case with changing AEDs regimen respectively. Among 9 patients, 1 failed to be followed up, 1 died, and 7 were followed up for 3 months to 2.5 years. Six patients had different degree abnormalities of ictal or interictal VEEG, though 1 case with normal VEEG outcome. One patient had normal neurological function, whereas other 6 patients had symptomatic epilepsy with different degree abnormalities of cognition in 5 patients and persistent vegetative state in one patient respectively.ConclusionClinical manifestations of NCSE in children with severe viral encephalitis may present with mouth, face and limb movement phenomena, cognitive and behavioral changes. The morphologies of ictal VEEG are various, in which the spike rhythmic activity may serve as a unique pattern. The measures of treatment and effective time are associated with NCSE types.

Nonconvulsive status epilepticus; Severe viral encephalitis; Video electroencephalography; Children

广州市妇女儿童医疗中心 1 神经内科;2 磁共振室;3 儿科重症监护室 广州,510623

陈文雄,E-mail:chenwx100@hotmail.com

10.3969/j.issn.1673-5501.2015.04.008

2015-04-30

2015-07-15)