“意指过程和差异的感受”特邀编辑概述

2023-10-07卓悦

卓 悦

I

讲座的第一部分对语言作为一个“不确定”的对象进行了思考。从英语中很少在“语言”一词前加定冠词这一现象出发,韦伯引用了德国文学评论家和哲学家维尔纳·哈马赫(Werner Hamacher)的论述,谈到了涉及所有语言的语言内部的“不断增殖”现象:“不存在一种语言,而是一种多样性;不是一种稳定的多样性,而只是一种语言的不断增殖。”(“95 Theses on Philology” 25)哈马赫认为,这种增殖既存在于语言内部,也存在于语言和语言之间。也许,语文学(philology)的新方法正是不把语言看作传统的、固定的对象,而是关注其内在的愉悦(德语:Genuß),即“不确定事物慢慢定义自己”的方式。这意味着,从语文学家的角度来看,研究者不仅要了解意义是如何通过过去的使用被关联并获得的,而且还要把能指从固定的意义中解放出来,使新的意义在未来能够重新关联和再生。

哈马赫将这种不确定的语言本身慢慢地定义自己的过程称为“多重语文学”(Archiphilologie)①。韦伯建议,理解这个概念的一种方式,是将其视为“回应”(response)和“呼吁”(appeal)之间的一种紧张关系:“回应先前已被固定使用的语义,并通过这种回应进一步呼吁将来的回应。”要理解这两个词的区别,我们首先要理解“回应”(response)和“回答”(answer)之间的区别,这两个在英语中相邻的词,具有不同的内涵。“回应”仍然接近于“回答”的词源(中世纪英语中的answere或andsware的意思),即简单的“回复”或“对应的话语”,而现代英语中“回答”(answer)承担的含义已狭隘化,成了对最初的陈述或问题“提供一个明确答案”的意思。所以“回答”(answer)这个词意味着一定程度的确定性,同时也表达了一种“明晰”的立场。

韦伯借助索绪尔在《普通语言学教程》中提出的语言内部差异功能的观点来强调两个观点:首先,在语言系统中,能指的意指过程是通过将自己与“周围”其他的能指(与自己相似又不相似的能指)区分开来的方式完成的。前文提到的“回应”和“回答”之间的关系就是一个例子。其次,虽然比较(comparing)和对比(contrasting)的过程以符号的某种稳定性为前提,但实际上所指并不是一个自理成章的概念,它本身就是一个过程和行为,需要时间才能实现“自身同一”和“意义独立”。

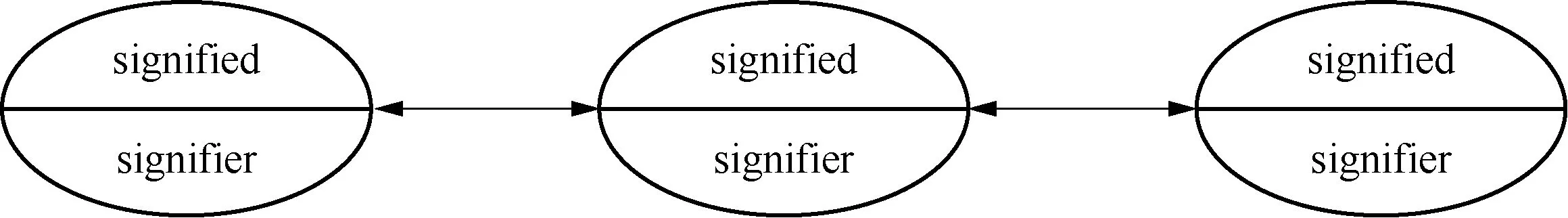

韦伯说的第一点里隐藏着索绪尔《普通语言学教程》中的“价值”概念,这一概念比符号的概念更鲜为人知,这里有必要回顾一下。根据索绪尔的说法,语言是一个相互依存的表达系统,其中每个符号的价值都是由与其他符号同时存在而产生的,如下图所示:

这句话的意思是:价值(value)不应该与意义(signification)相混淆。如果说意义是由下图中的垂直箭头决定的,即概念和音响形象之间的关系,那么价值指的是每个能指通过与其“周围”的音响形象“协商”而获得其含义的水平关系,这种协商关系通过差异性和相似性来获得。

回到回应(response)和呼吁(appeal)的问题,要理解语言和意指过程如何同时作为回应和呼吁发挥作用,我们需要了解回应(response)在多大程度上试着作为回答(answer)在运作,也就是说它怎样一味地“消除不确定性”。因此,这里的任务是让能指在意指过程中重新开始不确定的、多样性的游戏,无论是在它与过去,还是与未来的关系中。这种与过去和未来的紧张关系,不仅存在于纯粹的、形式的语言系统里,也存在于文学文本中。在第二部分,我们将以卡夫卡的短篇小说为例来说明这个问题。

II

如果在第一部分中,通过分析薄伽丘的《十日谈》,我们看到被传统约定的意义是如何在叙述行为中被重新定位、重构和取代的,那么在这一部分里,我们将考察卡夫卡的几个短篇小说以展示他的作品是对“一神论认同范式”(mono-theological identity paradigm)的一种防御性回应。这一范式(在此处可指奥匈帝国)似乎已不能维持自己,并表现出失控的症状,而这种防御性回应反过来又在文学文本中产生了一种紧张关系,需要仔细阅读才能体会。

韦伯分析的第一个故事是《中国长城建造时》(德语名:“Beim Bau der chinesischen Mauer”)。卡夫卡的这部短篇小说写于1917年,当时的奥匈帝国已明显处于衰败和消亡的阶段,而第一次世界大战使它更进一步地走向崩溃。作为一个主要生活在布拉格,讲德语的捷克犹太人,卡夫卡在奥匈帝国的双重外来性使他能够将叙事置于他实际生活的地域之外,即远离欧洲的中国。韦伯首先指出,小说标题中的“建造”一词很重要,因为“Beim Bau”这个词表明长城的“建造”仍处于正在进行时,就像故事本身一样未完成。他接着指出,尽管对这个故事有许多可能的解释,但我们在这里要讨论的主要问题是这个故事中对语言的反思。读者想知道的核心问题是中国长城是否已经竣工,但小说中对这个问题的描述是不确定的,因为它既说长城“被宣告完成”,又说在两端城墙合龙之后没在“一千米城墙的末端再接着修下去”(《中国长城建造时》 248)。因此,我们不能相信故事中的任何一则“声明”,事实上,这个故事被一种紧张关系支配着:它既有读者对建造完成的愿望(以便理解整个故事),也有文本自身结局的不确定性。

卡夫卡的这个短篇小说可以被解读为在不同的层面上的同时运作:一方面它是对世界帝国薄弱性的历史寄喻,另一方面也是对更普遍的语言本身的寄寓。这两个方面是如何共同发挥作用的?

故事中的叙述非常强调分工,也就是长城的模块化建造。读者被告知,即使长城竣工,也不足以克服它所使用的元素的零碎特性。“修长城是为了防御谁呢?是为了防御北方民族。我的家乡在中国的东南部。没有北方民族能在那里威胁我们。”(《中国长城建造时》 252)因此,“我们”听从来自高处的指令,但高处并不比我们知道得更多,甚至皇帝似乎也是一个懒惰的人(254)。渐渐地,随机投射的“外来敌人”的形象侵蚀了“保护”的概念:“修长城是为了防御北方民族。一个不连贯的长城又怎么能起到防御作用呢?当然不能,一个这样的长城非但不能防御,修城工程本身就处在不断的危险之中。”(248)

小说也可被认为是挑战语言作为一个聚合统一体的寄寓。试图建造一堵城墙来阻止“游牧民族”——来自北方的无拘无束的流浪者——的尝试可以被解读为语言中传统意义的固定性与持续的意指过程之间的紧张关系。换言之,城墙的未竣工与故事意义的不确定性有相似性。因此,韦伯写道,“阅读可以在复述文本中单词和短语所命题的内容,以及同时指出这些内容可以以其他方式阅读之间摇摆不定。”更具体一点说,故事中的语言提出了一些说法,但随后又将它们收回,从而挑逗了读者的定位欲望。韦伯称这种叙述为“渐进-漫谈”式叙述(他从劳伦斯·斯特恩《项狄传》的叙述者那里借用了这个术语),将这个过程称为“无声地召唤读者欲望”的“呼吁”过程:正是因为小说没有给出明确的答案,所以它吸引读者不断对文本意义进行追问。

《中国长城建造时》中的未完成感主要是由语言的不稳定性造成的,但在某些时候,使叙述变得曲折难测的“代理人”也会以具体、可见的形式出现在卡夫卡的作品中。《家父的忧虑》中的俄德拉代克就是一个例子——一个无生命的形状线轴变成了一个有生命的、会跳跃、发笑的东西,并回应了叙述者的问题(《家父的忧虑》 74)。在另一部不太为人所知的微型小说《教堂里的“紫貂”》中,这个“代理人”更引人注目:这是一只奇怪的貂类动物,它只有在祷告者开始祈祷时才会出现,除了听犹太教堂里人们的吁求之外,似乎什么也不做。更重要的是,它在“两指宽”的“突棱”(德语:Mauervorsprung)上大胆地前后蹦跃,这寓意着“渐进-漫谈”式的叙述(《教堂里的“紫貂》 502)。这些“令人不安”的叙述所实现的是对根基的质疑(无论是像不能环绕一整圈的城墙一样正在崩塌的帝国,还是对以线性因果为基础展开的传统叙事模式的期待),它们打开了地基,使新的建造成为可能。它们是“防御性的”,因为它们没有被封锁在有缺陷的、自我满足的传统意义中;它们先发制人地打开将要崩溃的地基,寻找新的意义和解决方案。

III

在第三部分,韦伯以讲解荷尔德林《对索福克勒斯〈安提戈涅〉的注释》一文来描述另一种对惯例的“推翻”(overturning)。荷尔德林将《安提戈涅》中的“推翻”描述为采取了他所谓的“vaterländische Umkehr”的形式。这个短语在英语中很难翻译,因为“Umkehr”(反转)影响了“Vaterland”(父国、祖国)一词②。今天,“祖国”(Fatherland)可能带有完全不同的内涵,比如殖民主义、帝国主义、旨在实现霸权的民族主义,包括世界各地的民族主义仇外心理。但是在荷尔德林写作的时候,也就是19世纪初的德国,在法国大革命之后的几年里,“vaterländische Umkehr”指的是这种霸权的反面,它可以被视为“一种将地方社会和政治存在的独异性与更普遍的愿望相结合的理想”(Weber,Singularity380)。韦伯强调,荷尔德林的模式从卡夫卡的反方向提供了一种可能性,因为诗人强调的是反转的局限性和坚持某些惯例的相对必要性。对荷尔德林来说,“vaterländische Umkehr”是“对各种表象和形式的反转”,它是一个永无止境的过程,没有任何一方是绝对的赢家或绝对的输家,因为每个“推翻”的一方,在努力争取更好的同时,也受制于自己的历史处境、他自己的“认知极限”。因此,“vaterländische Umkehr”是一个充满悖论、很难实现的计划,在历史的河流中,任何成功的反转形式都有可能被下一个反转所取消。

荷尔德林对索福克勒斯的忒拜三部曲,尤其是《俄狄浦斯王》和《安提戈涅》,表现出特别的兴趣,因为这两部戏剧展示了“无限的统一如何从无限的分离中净化出来”这一现象(Singularity12)。换一种说法,索福克勒斯的悲剧,尤其是《安提戈涅》,是体现“反转祖国”的绝佳案例,因为它维持了“反转祖国”形式中的一种紧张关系,而没有为了找到答案,仓促地断定谁是英雄、谁是恶棍。因此,荷尔德林在《安提戈涅》中看到了一种会被他的同代人所否定的东西,即一种“政治的、共和国的”理性形式(德语:Vernunftform)。

在荷尔德林写作的那个年代,拥护共和政体是很危险的,足以让一个人失去自由乃至生命,但荷尔德林却认为索福克勒斯的政治框架仍然是有效,甚至是有用的,即使在荷尔德林自己的历史情境中它只是“勉强”可行。这应该如何理解?荷尔德林所说的理性的“共和”形式,在这里具体指的是克瑞翁和安提戈涅之间所维持的一种平衡。与许多评论家不同,荷尔德林并没有简单地谴责克瑞翁并赞美安提戈涅,他欣赏的正是索福克勒斯在普遍利益与个人利益之间保持了一种张力:前者以克瑞翁禁止埋葬波吕尼克斯(忒拜的叛国者)为代表,后者以安提戈涅违抗克瑞翁的法令和她为了表达对哥哥的感情牺牲自己为体现。安提戈涅和克瑞翁都蒙受耻辱,但他们受辱的方式截然不同:安提戈涅是因为不服从克瑞翁的法令以及法令下的民法,而克瑞翁则是因为他的古板和在体谅生命之脆弱与有限上表现出的无能。克瑞翁的错误在于,他将生者和死者相提并论,禁止一个妹妹为自己无可替代的胞兄之死而哀悼,这是不理解一个具有道德和政治行为的活人(叛国者)与一具不埋葬就将沦为牲畜的尸体之间存在区别的一种标志。

在《对索福克勒斯〈安提戈涅〉的注释》的结尾,荷尔德林得出结论:尊重传统仍有其必要性。索福克勒斯的戏剧提供了祖国模式想象的一个绝佳范例,因为它在展示普遍性和独异性“共存”(德语:zugleich)的同时,也指出了它们的不平等(德语:ungleich)。这种“共和”模式开启了一个无穷的知识空间,“就像国家和世界的精神一样”,这个知识空间只能从“倾斜”(德语:linkische)的角度,或者以“巧妙笨拙”(法语:adroitly gauche)的方式才能把握住。荷尔德林的意思是,我们对时代精神的理解总是有限的;真正的知识更多地取决于不能完全被理解的东西,而不是习惯上获得的知识。然而,不能完全了解或以“巧妙笨拙”的方式了解的那部分,经常可以被我们感受到,而诗人的作用恰恰是“保留和感受”未说出的部分,即“深不可测的差异关系”。这让我们回到了城墙不能连接成一个完整圆圈的形象。所指本身也是一个能指,永远指向无尽的循环:“它指向自身,但同时(zu gleich)又指向不平等(ungleich),即与自身不同的东西。”韦伯认为,人类不仅是认知的存在,也是有感知的存在。真正的意义从来都不是简单地通过文字来表达的,而是被“倾斜”地感知,或者在两个手指之间的空间中被感知,这个空间,即是语文学(philology)的“对象”。

注释[Notes]

① Archiphilologie一词的前缀“archi-”既有“早期”“原始”“第一”“最重要”的意思,也有architecture (建筑)一词中所包含的“构造”和“累加”的含义。哈马赫的Archiphilologie概念在强调语言本身的多重性和加建性的同时,也指出它的非本体性,即语言可以不受意义、对象、目的的限制,在其内部无限地扩展自己自由游戏的空间。

② “Vaterländische Umkehr”(德语)可译为“爱国主义的反转”,也可译为“回归自己的国家”。1959年,保罗·德曼在布兰迪斯大学一次关于荷尔德林与浪漫主义传统的讲座中首次探讨了这一说法的复杂性。参见De Man, Paul. “Hölderlin and the Romantic Tradition,” “Hölderlin and the Romantic Tradition.”Diacritics40.1(2012):115。

引用作品[Works Cited]

De Man, Paul. “Hölderlin and the Romantic Tradition.”Diacritics40.1(2012):100-129.

Hamacher, Werner. “95 Theses on Philology.” Trans. Catherine Diehl.Diacritics39.1(2009):25-44.

弗朗兹·卡夫卡:《中国长城建造时》,薛思亮译,《卡夫卡小说全集Ⅲ》,韩瑞祥等译。北京:人民文学出版社,2003年。248—257。

[Kafka, Franz. “Building the Great Wall of China.” Trans. Xue Siliang.TheCompleteFictionofKafka. Vol.3. Trans. Han Ruixiang, et al. Beijing: People’s Literature Publishing House, 2003.248-257.]——:《家父的忧虑》,杨劲译,《卡夫卡小说全集III》,韩瑞祥等译。北京:人民文学出版社,2003年。74—75。

[---. “The Cares of a Family Man.” Trans. Yang Jing.TheCompleteFictionofKafka. Vol.3. Trans. Han Ruixiang, et al. Beijing: People’s Literature Publishing House, 2003.74-75.]——:《教堂里的“紫貂”》,叶廷芳译,《卡夫卡全集第一卷》,叶廷芳主编,叶廷芳、黎奇等译。北京:中央编译出版社,2015年。501—504。

[---. “In Our Synagogue.” Trans. Ye Tingfang.TheCompleteWorksofKafka. Vol.1. Ed. Ye Tingfang. Trans. Ye Tingfang and Li Qi, et al. Beijing: Central Compilation and Translation Press, 2015.501-504.]

Weber, Samuel.Singularity:PoliticsandPoetics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2021.

Overview of Lecture 2:SignifyingandtheFeelingofDifferences

I

The first part of the lecture is devoted to the reflection of language as an “indeterminate” object. Starting from the fact that in English, the word “language” is rarely refered to with a definite article, Weber quotes the German critic and philosopher Werner Hamacher to speak of a “perpetual multiplication” within language that affects all languages: “There is noonelanguage but a multiplicity; not a stable multiplicity but only a perpetual multiplication of languages” (“95 Theses on Philology” 25). This multiplication, according to Hamacher, exists both at an intralinguistic and an interlinguistic level. Perhaps the new approach to philology is precisely not to view language as a traditional, stable object, but to focus on its inner enjoyment (Genuß), i.e., the way in which “the indefinite slowly defines itself” (43). This means, from the philologist’s point of view, one should not only see how meaning is associated and gained through past usage, but also free the signifier from fixed meanings for future associations.

Hamacher calls this process of the indefinite of language slowly defining itself “archiphilology”①.One way of understanding it, Weber suggests, is to see it as a tension between “response” and “appeal”: “responding to previous attempts at appropriation, and through such responses appealing for further responses.” In order to understand this distinction, however, one first has to understand the difference between “response” and “answer,” two neighboring words in English which have different connotations. While “response” remains close to the etymological roots of “answer” —answereorandswarein Middle English — meaning simply a “counter-affirmation” or “countering word,” the modern English word “answer” has taken on a more limited meaning of “providing a definite solution” to the initial statement or question. The word “answer” entails a degree of certainty, and together with it, a position of “knowing.”

Weber resorts to Saussure’s view of intra-linguistic, differential function in language, developed in the linguist’sCourseinGeneralLinguistics, to emphasize two points. First, in the linguistic system, signifiers signify by differentiating themselves from other signifiers that “surround” them, that is, those bear both a resemblance and dissemblance to the signifier in question. Such is the relation between “response” and “answer.” Second, although the process of comparing and contrasting presupposes a certain stability of the sign, in reality the signified is not a taken-for-granted idea, itself being a process and an action; i.e., it needs time to become “self-identical” and “self-contained.”

Implicit in the first point is Saussure’s concept of value in theCourseinGeneralLinguistics, which, lesser-known than the concept of the sign, needs to be reminded here. According to Saussure, language is a system of interdependent terms in which the value of each sign results solely from the simultaneous presence of others, as the following diagram shows:

What it means is that value should not be confused with signification. Whereas signification is defined by the vertical arrows in the drawing below, namely, the relation between sound image and concept, value refers to the horizontal relation in which each signifier acquires its meaning by “negotiating” with its “surround” sound image/signifiers, through dissemblance and similarity.

To come back to the question of response and appeal and to understand the how language and signifying process function both as response and appeal, we need to see how muchresponsetries to operate as ananswer, i.e., to always want to “eliminate uncertainty.” The task here is therefore to reinstall the play of indeterminate multiplicity of signifiers in the process of signifying, both in relation to the past and to the future. This tension in relation to the past and to the future is not limited to the purely formal linguistic system; it operates also in literary texts, as Kafka’s short stories illustrate in the second part.

II

If, in the first lecture, Boccaccio’sDecameronis analyzed to show how established conventions of meaning are resituated, reframed and displaced in the act of recounting, here, in this section, several of Kafka’s short stories are examined to show a defensive response to a “monotheological identity paradigm” (for instance the Austro-Hungarian Empire) that is no longer holding itself well and is displaying symptoms of losing control. This defensive response in turn produces a tension within the literary texts that require close reading.

The first story Weber analyses is “While Building the Wall of China” (German: “Beim Bau der chinesischen Mauer”). Written in 1917, Kafka’s short story was written during the definite decline and demise of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which was further diminished by the First World War. As a German-speaking Czech Jew living mainly in Prague, Kafka’s double foreignness to the Austro-Hungarian Empire allows him to situate the narrative outside where he actually lives, namely, far away from Europe — in China. Weber first points out the word “building” in the title is important, since the word “Beim Bau” suggests that the “building” of the wall is ongoing and is as unfinished as the story itself. He then points out that although there are many interpretations possible of this story, the main issue that will occupy us here is that the story involves a reflection on language. The central question that the reader wants to know is whether the Chinese Wall was completed or not. But the language that describes this fact is uncertain, since it says both that the wall “was declared to be completed” and that “the building was not continued at the end of the thousand meters” (BuildingtheGreatWall113, translation modified by Weber). We cannot therefore trust any of these “declarations” in the story, and indeed, the story is animated by a tension between the desire for completion (to understand the story) and the inconclusiveness of the text itself.

Kafka’s story can be read as operating at different levels simultaneously. On the one hand as an historical allegory of the vulnerability of global empires, and on the other as an allegory of a more general linguistic one. How do the two function together?

In the story, much emphasis is placed on the division of labor, which is the modular construction of the Great Wall. One is made to understand that even the completion of the Wall will not suffice to overcome the fragmentary character of the elements with which it is working. “From whom is the Great Wall supposed to protect us? From the people of the north. I come from Southeastern China. No northern people can threaten us there” (BuildingtheGreatWall117). We therefore listen to the command from a higher place, but the high command does not know more than we do, even the emperor seems to be a lazy person who does not do much (119). Little by little, the projection of a random enemy outside compromises the notion of protection: “The wall was conceived of as a defense against the people of the north, but how can a wall that is not a continuous structure offer protection? Indeed, not only can such a wall not protect, but the construction itself is in perpetual danger” (113).

The second allegory is the allegory of challenging language as a coherent unity. The attempt to construct a wall to keep out the “nomads” — the uncontrolled wanderers from the north — can be read as an allegory of tension between the fixity of traditional meaning of language and an ongoing signifying process. In other words, the incompletion of the construction of the Wall is similar to the inclusiveness of the meaning of the story. “Reading can thus oscillate between essentially reproducing the propositional content of words and phrase in the text,” writes Weber, “and indicating how such content can be read otherwise than as simply reproducing conventional meanings ....” More concretely, it means the language in the story proposes something, but then takes back, thus teasing the reader’s desire for orientation. Weber calls this type of narration “progressive-digressive” (a term he borrowed from the narrator of Laurence Sterne’sTristramShandy) and this silent calling for the reader’s desire the process “appealing.” It is precisely because it does not give a clear answer to the meaning that it appeals to you to keep asking questions.

While the sense of incompletion in “While Building the Wall of China” is largely created by the instability of language, occasionally the agent that makes the narration twist and turn appears in Kafka’s writing as a concrete, visible thing. Such is the case of Odradek in the story “The Cares of a Family Man,” in which an inanimate object — a star-shaped spool for thread — becomes an animate being that not only lurks and laughs, but also responds to the narrator’s questions. A more striking example is found in in a lesser-well-known story called “In Our Synagogue,” in which a strange marten-like animal seems to do nothing in the synagogue other than listening to our appeals: it appears only when the church attenders start to pray. More importantly, it is the “two-fingers wide” “protruding ledge” (Mauervorsprung) on which it makes the audacious leap, both forward and backward, that is allegorical of the “progressive-digressive” narration (“In our Synagogue” 141-142). What these “unsettling” narratives achieve is a questioning of the foundation (whether it is collapsing empire resembling the Wall that does not come full-circle or the conventional expectations of a linear-causal unfolding of meaning) while opening it up for new constructions. They are “defensive” in that they are not caught in the flawed self-sufficient conventions; they preemptively open the collapsing foundations in search for new meanings and solutions.

III

In the third part, Weber examines Hölderlin’s “Remarks on Sophocles’Antigone” to describe another kind of the “overturning” of conventions. Hölderlin describes the “overturning” inAntigoneas taking the form of what he callsvaterländischeUmkehr— a phrase that is difficult to translate in English becauseUmkehr(reversal) has affected the wordVaterland(Fatherland)②. Today “fatherlandic” may mean something totally different, like colonial, imperial, nationalistic efforts aimed at hegemony, including nationalist xenophobia all over the world. But, at the time Hölderlin writes, that is to say Germany at the beginning of the nineteenth century, during the years immediately following the French Revolution,vaterländischeUmkehrrefers to the opposite of such hegemony; it could be seen as “an ideal combining the singularities of local social and political existence with more general aspirations” (Singularity, 380). Weber emphasizes that Hölderlin’s model offers an alternative to that of Kafka, for the poet stresses the limits of reversal and the relative need to hold on to certain conventions. For Hölderlin,vaterländischeUmkehris “the overturning of all kinds of representation and of forms;” it is anunendingprocess that no party comes out as the absolute winner or absolute loser, because each “overturning” party, while striving for the better, is also at the same time conditioned by its own historical situation, his own “cognitive limit.” Therefore,vaterländischeUmkehris an aporetic enterprise in which any successful form of reversal could always potentially be cancelled by the next one in the continuous flow of history.

Hölderlin shows a particular interest in Sophocles’ Theban tragedies, in particularOedipustyrannosandAntigone, because the two plays demonstrate how “limitless unification purges itself through limitless separation” (Singularity12). To put it differently, Sophocles’ plays, especiallyAntigone, serve as good examples to show how the tension around “fatherlandic reversal” can be sustained instead of deciding hastily on the heroes and villains. Hölderlin thus sees inAntigonesomething that would be repudiated by his contemporaries, namely aformofreason(Vernunftform) that “is political, and namely republican.”

At the time when Hölderlin was writing, republican sympathies were dangerous, sufficient to cost one one’s liberty or even one’s life, yet Hölderlin argues that Sophocles’ political framework, although “barely” workable in Hölderlin’s own historical situation, is still valid, and even useful. How so? What Hölderlin calls the “republican” form of reason here refers more specifically to the maintaining of the equilibrium between Creon and Antigone. Unlike many commentators, Hölderlin does not write off Creon and extol Antigone; what he appreciates in Sophocles is precisely the maintaining of the tension between the interests of the general, represented by Creon’s interdiction of burying Polynices, Thebe’s traitor, and of the singular, incarnated by Antigone’s defiance to Creon’s decree and her feelings for her brother. Both Antigone and Creon suffer disgrace, but they suffer in very different ways: Antigone for not obeying Creon’s edict and by consequence the civil law, and Creon for his inflexibility and incapability of understanding the vulnerability and mortality of the living. Creon’s fault was that he treated “too equally” the living and the dead, since forbidding a sister to mourn the death of an irreplaceable brother, is a sign of not understanding the difference between a living being, with moral and political deeds, and a dead body, which, without burial, would be reduced to the finitude of other living animals.

Toward the end of “Remarks on (Sophocles’)Antigone,” Hölderlin concludes that respect for the tradition is still needed. Sophocles’ play offers a good example of the fatherlandic modes of imagining, by exposing the general and the singularatonce(zugleich), while pointing toward the unequal (ungleich). This “republican” mode opens onto anunendingspace of knowledge, which, “like the spirit of states and of the world,” can only be grasped only from a “skewed” (linkische) point of view, or an “adroitly gauche” manner. What Hölderlin means here is that our understanding of the spirit of the time is always limited; the true knowledge depends more on what cannot be fully understood, than on the traditional sense of knowledge. That part that cannot be entirely known, or known in an “adroitly gauche” (linkische) way, can, however, often be felt, and it is precisely the poet’s role to “retain and to feel” what remained unsaid, that “unfathomable relation of difference.” This brings us back to the image of the wall never completely come into a full circle. The signified, being always already itself a signifier, can never conclude the circle of pointing: “It points to itself, and yet always at once (zugleich), simultaneously towards theungleich: toward that which is not the same itself.” Human beings, Weber suggests, are not only cognitive beings, but also sentient beings; true meaning is never simply signified through words, but left to be perceived “skewedly,” or be felt in that two-finger, in-between space that is also the “object” of philology.

[Notes]

① The prefix “archi-” in the word “archiphilologie” means “earlier,” “original,” “first,” “chief,” as well as “building” or “assemblage” as contained in the word “architecture.” Hamacher’s concept of “Archiphilologie,” while emphasizing the multiplicity and constructiveness of language itself, also points out its non-ontological nature, that is, language can expand its own free play indefinitely without being limited by the concerns for meaning, addressee and purpose.

②VaterländischeUmkehrcan be translated as “patriotic reversal,” but also “the return toward one’s own nation.” Paul de Man was the first to explore the complexity of this term in a lecture he delivered at Brandeis university in 1959. See Paul de Man, “Hölderlin and the Romantic Tradition.”Diacritics40.1(2012):115.

[Works Cited]

De Man, Paul. “Hölderlin and the Romantic Tradition.”Diacritics40.1(2012):100-129.

Hamacher, Werner. “95 Theses on Philology.” Trans. Catherine Diehl.Diacritics39.1(2009):25-44.

Kafka, Franz. “Building the Great Wall of China.”Kafka’sSelectedStories. Tran. Stanley Conrgold. New York: Norton, 2007.113-123.

---. “In Our Synagogue.” Franz Kafka.InvestigationsofaDogandOtherCreatures. Trans. Michael Hofmann. New York: New Directions, 2017.140-143.

Weber, Samuel.Singularity:PoliticsandPoetics, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2021.