东西方国家急性坏死性胰腺炎影响因素的Meta分析

2023-04-29马书丽杨晓曦陈晨喻静周游路国涛向晓星龚卫娟陈炜炜陈娟

马书丽 杨晓曦 陈晨 喻静 周游 路国涛 向晓星 龚卫娟 陈炜炜 陈娟

摘要:

目的 探討东西方国家急性坏死性胰腺炎(ANP)及感染性坏死性急性胰腺炎(IPN)影响因素的区别,为预测和预防ANP的发生提供理论依据。方法 在PubMed、Embase、Cochrane library、Web of Science等数据库检索公开发表的有关ANP、IPN的影响因素,检索期限为建库至2021年1月21日,运用Meta分析方法进行整合分析。结果 共纳入59项研究,其中22项来自东方国家,37项来自西方国家。结果显示, ANP的影响因素:在东方为男性(OR=1.51,95%CI:1.18~1.91,P<0.01)、CRP(SMD=1.39,95%CI:1.06~1.71,P<0.01)、D-二聚体(SMD=0.44,95%CI:0.07~0.81,P=0.02)、APACHE-Ⅱ评分(MD=3.51,95%CI:1.38~5.64,P<0.01)、酒精性病因(OR=3.57,95%CI:2.68~4.75,P<0.01)、胆源性病因(OR=0.60,95%CI:0.46~0.77,P<0.01);在西方为男性(OR=1.63,95%CI:1.30~2.05,P<0.01)、CRP(SMD=2.09,95%CI:1.12~3.05,P<0.01)、APACHE-Ⅱ评分(MD=4.28,95%CI:2.73~5.83,P<0.01)、Ranson评分(MD=2.99,95%CI:2.50~3.47,P<0.01)和器官衰竭(OR=10.87,95%CI:2.62~45.04,P<0.01)。IPN的影响因素:在东方为年龄(MD=2.16,95%CI:0.43~3.89,P=0.01)、BMI(MD=1.74,95%CI:1.23~2.25,P<0.01)、白蛋白水平(SMD=-0.43,95%CI:-0.75~-0.12,P<0.01)、CRP(SMD=0.58,95%CI:0.04~1.11,P=0.03)、PCT(SMD=0.80,95%CI:0.56~1.04,P<0.01)、D-二聚体(MD=0.23,95%CI:0.15~0.31,P<0.01)、APACHE-Ⅱ评分(MD=2.47,95%CI:0.73~4.22,P<0.01)、Ranson评分(MD=1.60,95%CI:1.46~1.73,P<0.01)和坏死范围≥30%(OR=2.52,95%CI:1.26~5.06,P<0.01);在西方为年龄(MD=4.07,95%CI:1.82~6.31,P<0.01)、APACHE-Ⅱ评分(MD=3.28,95%CI:1.39~5.17,P<0.01)、Ranson评分(MD=2.18,95%CI:1.75~2.62,P<0.01)、SIRS评分(OR=3.88,95%CI:1.58~9.51,P<0.01)、酒精性病因(OR=0.61,95%CI:0.42~0.87,P<0.01)和器官衰竭(OR=3.63,95%CI:1.11~11.92,P=0.03)。结论 当前证据显示,东方人群ANP的特异性影响因素为胆源性病因及酒精性病因,而Ranson评分是西方人群ANP的特异性影响因素;BMI和坏死范围≥30%是东方人群IPN特异性影响因素,酒精性病因是西方人群IPN特异性影响因素。

关键词:

胰腺炎, 急性坏死性; 影响因素; Meta分析

基金项目:

国家自然科学基金(82004291);江苏省自然科学基金(BK20190907);江苏省六大人才高峰项目(WSN-325)

Influencing factors for acute necrotizing pancreatitis in Eastern and Western countries: A Meta-analysis

MA Shuli1,2,3, YANG Xiaoxi1,3, CHEN Chen3, YU Jing3, ZHOU You3, LU Guotao4, XIANG Xiaoxing1, GONG Weijuan3, CHEN Weiwei1, CHEN Juan1. (1. Department of Gastroenterology, Subei Peoples Hospital, Yangzhou, Jiangsu 225000, China; 2. Department of Gastroenterology, Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University, Nantong, Jiangsu 226000, China; 3. School of Nursing, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, Jiangsu 225000, China; 4. Department of Gastroenterology, The Affiliated Hospital of Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, Jiangsu 225000, China)

Corresponding author:

CHEN Juan, chenjuan406512@163.com (ORCID: 0000-0002-2181-2636)

Abstract:

Objective To investigate the differences in the influencing factors for acute necrotizing pancreatitis (ANP) and infectious pancreatic necrosis (IPN) between Eastern and Western countries, and to provide a theoretical basis for the prediction and prevention of ANP. Methods Databases including PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, and Web of Science were searched for articles on the influencing factors for ANP and IPN published up to January 21, 2021, and a Meta-analysis was performed. Results A total of 59 studies were included, with 22 studies from Eastern countries and 37 studies from Western countries. The Meta-analysis showed that in Eastern countries, male sex (odds ratio [OR]=1.51, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.18-1.91, P<0.01), C-reactive protein (CRP) (standardized mean difference [SMD]=1.39, 95%CI: 1.06-1.71, P<0.01), D-dimer (SMD=0.44, 95%CI: 0.07-0.81, P=0.02), Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE-II) score (mean difference [MD]=3.51, 95%CI: 1.38-5.64, P<0.01), alcoholic etiology (OR=3.57, 95%CI: 2.68-4.75, P<0.01), and biliary etiology (OR=0.60, 95%CI: 0.46-0.77, P<0.01) were the influencing factors for ANP, and in Western countries, male sex (OR=1.63, 95%CI: 1.30-2.05, P<0.01), CRP (SMD=2.09, 95%CI: 1.12-3.05, P<0.01), APACHE-II score (MD=4.28, 95%CI: 2.73-5.83, P<0.01), Ranson score (MD=2.99, 95%CI: 2.50-3.47, P<0.01), and organ failure (OR=10.87, 95%CI: 2.62-45.04, P<0.01) were the influencing factors for ANP. In Eastern countries, age (MD=2.16, 95%CI: 0.43-3.89, P=0.01), body mass index (BMI) (MD=1.74, 95%CI: 1.23-2.25, P<0.01), albumin level (SMD=-0.43, 95%CI: -0.75 to -0.12, P<0.01), CRP (SMD=0.58, 95%CI: 0.04-1.11, P=0.03), procalcitonin (SMD=0.80, 95%CI: 0.56-1.04, P<0.01), D-dimer (MD=0.23, 95%CI: 0.15-0.31, P<0.01), APACHE-II score (MD=2.47, 95%CI: 0.73-4.22, P<0.01), Ranson score (MD=1.60, 95%CI: 1.46-1.73, P<0.01), and extent of necrosis ≥30% (OR=2.52, 95%CI: 1.26-5.06, P<0.01) were the influencing factors for IPN, while in Western countries, age (MD=4.07, 95%CI: 1.82-6.31, P<0.01), APACHE-II score (MD=3.28, 95%CI: 1.39-5.17, P<0.01), Ranson score (MD=2.18, 95%CI: 1.75-2.62, P<0.01), SIRS score (OR=3.88, 95%CI: 1.58-9.51, P<0.01), alcoholic etiology (OR=0.61, 95%CI: 0.42-0.87, P<0.01), and organ failure (OR=3.63, 95%CI: 1.11-11.92, P=0.03) were the influencing factors for IPN. Conclusion Current evidence shows that biliary etiology and alcoholic etiology are unique influencing factors for ANP in the Eastern population, while Ranson score is a unique influencing factor in the Western population. BMI and extent of necrosis ≥30% are unique influencing factors for IPN in the Eastern population, while alcoholic etiology is a unique influencing factor in the Western population.

Key words:

Pancreatitis, Acute Necrotizing; Influencing Factors; Meta-analysis

Research funding:

National Natural Science Foundation (82004291); Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20190907); Six Talent Peaks Project of Jiangsu Province (WSN-325)

急性胰腺炎(acute pancreatitis, AP)是消化科最常见的疾病,绝大部分AP患者是轻度且自限性的。但10%~20%的患者可进展成为急性坏死性胰腺炎(acute necrotizing pancreatitis, ANP),其中33%的患者仍会进一步进展为病死率更高的感染性坏死性急性胰腺炎(infected pancreatic necrosis, IPN)[1-4]。目前临床上,ANP的诊断主要采用增强CT(contrast-enhanced computed tomography, CECT),CECT显示胰腺或胰腺周围坏死组织内有小而不规则的气泡或细针穿刺(fine needle aspiration, FNA)细菌培养呈阳性提示为IPN,然而在疾病早期,尤其是发病48~72 h内CECT很少能诊断出ANP,且大约一半的IPN患者CECT不显示有气体,FNA并非常规操作,增加早期识别的难度[5]。而提早发现高危患者对临床管理和预后至关重要。

由于AP的病因、治疗和遗传易感性在东西方存在差异,因此ANP和IPN的影响因素也可能不同。本研究旨在识别并分析早期的风险因素,探讨这些因素在东西方国家ANP和IPN的预测和防治方面的价值。

1 资料与方法

1.1 规程与注册 本研究根据PRISMA指南完成,已在PROSPERO注册(CRD42021168942)。

1.2 检索策略 检索了PubMed、Embase、Cochrane Library和Web of Sci等数据库,检索时间均从建库到2021年1月21日。以“Pancreatitis”,“Pancreatitis, Acute Necrotizing”主题词与自由词相结合的方式进行检索,并联合文献追溯法进行手动检索。

1.3 纳入与排除标准 纳入标准:(1)以英文发表;(2)患者年龄≥14岁;(3)观察性研究;(4)胰腺坏死需由CECT或活检或有经验的外科医生手术中诊断,而IPN则由CECT上存在气泡征或经FNA引流或坏死切除获得的胰腺或胰腺外组织提示培养呈阳性确诊;(5)ANP文献中纳入的生化标志物和评分系统需要在72 h内获得,而IPN的相关因素无时间限制。

排除标准:(1)样本量≤5个;(2)非原始研究,包括会议摘要、个案报告、信件、专家意见、评论等;(3)无法提取数据;(4)无法获得全文。

1.4 数据提取与质量评估 使用EndNote X9软件严格按照纳入和排除标准进行文献筛选;采用纽卡斯尔-渥太华量表(Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, NOS)评估队列研究和病例对照研究的质量;提取数据包括:第一作者、国家(东方和西方)、出版年份、研究设计、研究人群(ANP和IPN)、風险因素等。文献筛选、质量评估和数据提取均由两名研究者独立完成,有分歧由两名研究者讨论,若仍无法达成一致由通信作者裁决。

1.5 东西方概念的界定 本研究共涉及20个国家,将地理位置处于欧洲和北美的国家定义为西方国家。处于亚洲的定义为东方。根据Mak等[6]的研究,将处于交接处的土耳其定义为东方国家。

1.6 统计学方法 使用RevMan 5.3统计软件进行数据分析。分类变量以OR和95%CI表示,连续变量以均方差(mean difference,MD)或标准化均方差(standardized mean difference, SMD)及95%CI表示。参考Hozo等[7]和Wan等[8]提出的方法将中位数、范围或四分位数转化x±s。采用Q检验和I2检验评估异质性。当P>0.1和I2<50%时,采用固定效应模型;否则,采用随机效应模型[9]。当I2<75%和P>0.05被认为是低异质性[10]。当异质性高时,进行敏感性分析,必要时根据研究特征进行亚组分析。漏斗图用于检测发表偏倚。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

根据van der Vlist等[11]和Kunze等[12]的研究,将风险因素分为强、中度、弱、边缘或无证据。(1)强有力证据:所纳入研究中,不止一项研究的NOS评分>7分,且≥75%的研究报告结果一致或OR值>2.0/<0.8,P<0.05。(2)中度证据:所纳入研究中,一项研究的NOS评分>7分,且≥75%的研究报告结果一致或OR值为1.5~2.0/0.8~0.9,P<0.05。(3)弱证据:所纳入研究中,≥75%的研究报告结果一致或OR值为1.0~1.5/0.9~1.0,P<0.05。(4)边缘或无证据:所纳入研究中,<75%的研究报告结果一致或P≥0.05。

2 结果

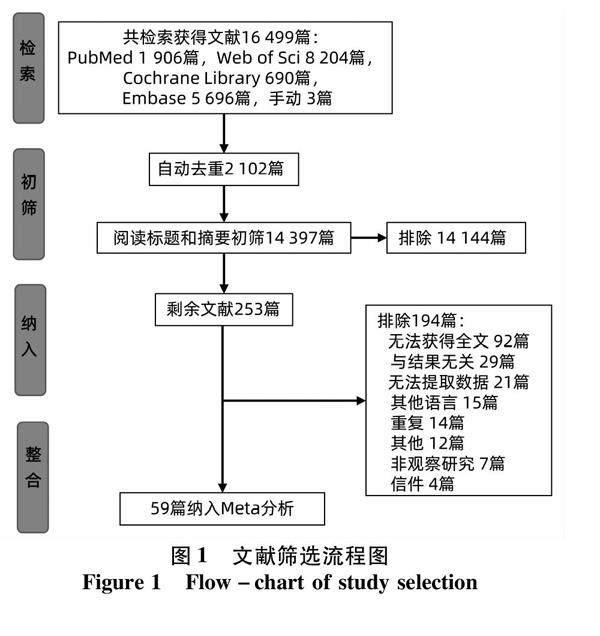

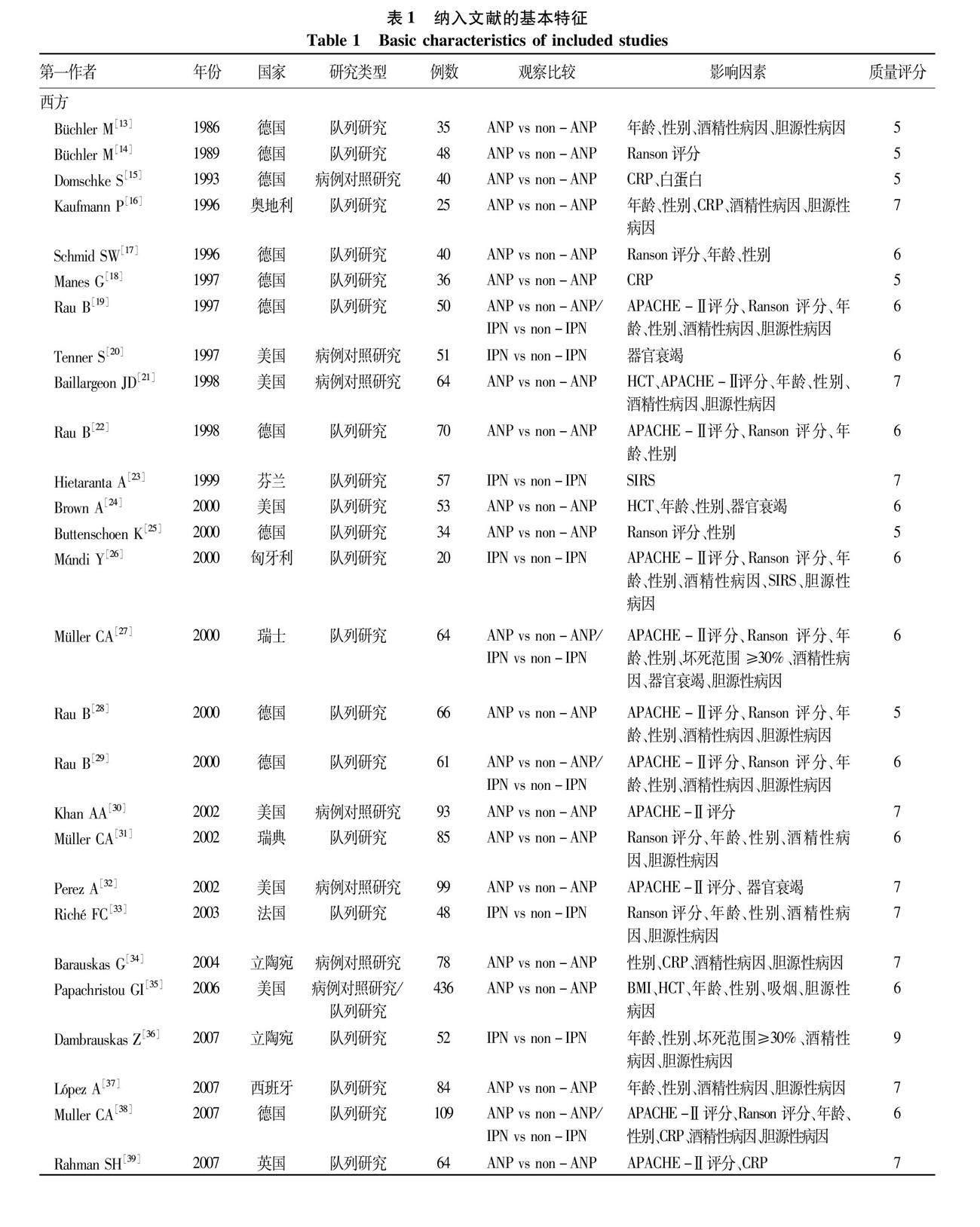

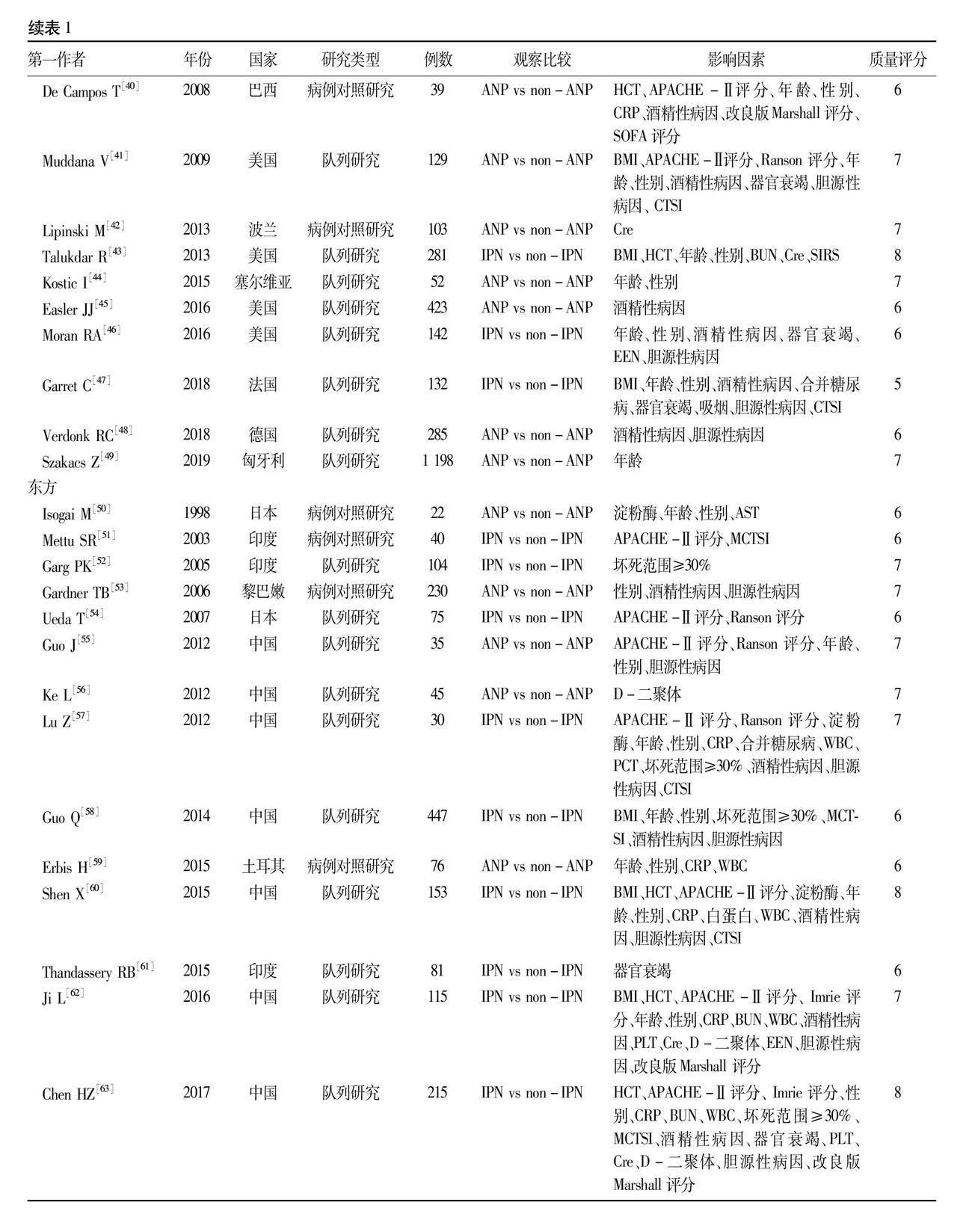

2.1 文献检索结果 初步纳入文献16 499篇,在去重、查阅标题和摘要之后剩余253篇,进一步阅读全文,最终纳入文献59篇[1,4,13-69],其中37篇[13-49]来自西方,22篇[1,4,50-69]来自东方,具体见图1所示,纳入文献特征见表1。纳入文献发表于1986—2019年,其中43篇为队列研究,16篇为病例对照研究。共包括来自20个国家的12 625例患者,主要涉及国家为德国、美国和中国,共评估66个影响因素,其中30个符合Meta分析要求。所纳入文献NOS评分均≥5分,提示文献质量相对较高[70]。

2.2 ANP的影响因素 共39项[13-19, 21-22, 24-25, 27-32,

34-35, 37-42, 44-45, 48-50, 53, 55-56, 59, 64, 65, 67-69]研究报告了与ANP相关的影响因素。整体人群的Meta分析显示,ANP的影响因素包括:男性[13, 16-17, 19, 21-22,

24-25, 27-29, 31, 34-35, 37-38, 40-41,44, 50, 53, 55, 59, 65, 67-68]、Cre[42, 65]、CRP[15-16, 18, 34, 38-40, 59, 64, 68]、D-二聚体[56, 64, 69]、APACHE-Ⅱ 评分[19, 21-22, 28-30, 32, 39-41, 55, 64]、Ranson评分[14, 17, 19, 22, 25, 27-29, 31, 38, 41, 55, 65]、酒精性病因[13,16,19,21, 27-29, 31, 34, 37-38, 40-41, 45, 48, 65, 68]、吸烟[35, 65]和器官衰竭[24, 27, 32, 41]。西方ANP的影响因素为男性(OR=1.63,P<0.01)、CRP(SMD=2.09,P<0.01)、APACHE-Ⅱ评分(MD=4.28,P<0.01)、Ranson评分(MD=2.99,P<0.01)和器官衰竭(OR=10.87,P<0.01)(表2);东方ANP的影响因素为男性(OR=1.51,P<0.01)、CRP(SMD=1.39,P<0.01)、D-二聚体(SMD=0.44,P=0.02)、APACHE-Ⅱ评分(MD=3.51,P<0.01)、酒精性病因(OR=3.57,P<0.01)、胆源性病因(OR=0.60,P<0.01)(表3)。结果提示,东西方影响因素的差异表现在D-二聚体、Ranson评分、器官衰竭、胆源性病因和酒精性病因上。敏感性分析表明结果具有可靠性。

2.3 IPN的影响因素 共26项[1, 4, 19, 20, 23, 26-27, 29, 33, 36, 38, 43, 46-47, 51-52, 54, 57-58, 60-64, 66]研究调查了与IPN相關的影响因素,整体人群Meta分析结果表明,IPN的影响因素包括年龄[4, 19, 26-27, 29, 33, 36, 38, 43, 46-47, 57-58, 60, 62, 66]、白蛋白[60, 66]、BMI[43, 47, 58, 60, 62, 66]、CRP[38, 57, 60, 62-63, 66]、PCT[57, 63, 66]、D-二聚体[62-63]、APACHE-Ⅱ 评分[19, 26-27, 29, 38, 51, 54, 57, 60,62-63]、Ranson评分[19, 26-27, 29, 33, 38, 54, 57]和坏死范围≥30%[4, 27, 36, 52, 57-58, 63, 66]。因研究间的异质性较大,进一步分析了以IPN和无菌性坏死性急性胰腺炎(sterile pancreatic necrosis, SPN)为研究对象的亚组。结果表明,年龄[19, 26-27, 29, 36, 38, 46, 58]、WBC[58, 63]、CRP[38, 63]、APACHE-Ⅱ评分[19, 26-27, 29, 38, 51, 54, 63]、Ranson评分[19, 26-27, 29, 38, 54]和坏死范围≥30%[27, 36, 52, 58, 63]是SPN进展为IPN的影响因素。为进一步比较东西方影响因素的差异,按研究对象的地域分为东西方两个亚组。结果显示:在西方,IPN的影响因素为年龄(MD=4.07,P<0.01)、APACHE-Ⅱ评分(MD=3.28,P<0.01)、Ranson评分(MD=2.18,P<0.01)、SIRS(OR=3.88,P<0.01)、酒精性病因(OR=0.61,P<0.01)和器官衰竭(OR=3.63,P=0.03)(表4);在东方人群中,与IPN相关的影响因素是年龄(MD=2.16,P=0.01)、BMI(MD=1.74, P<0.01)、白蛋白水平(SMD=-0.43,P<0.01)、CRP(SMD=0.58,P=0.03)、PCT(SMD=0.80,P<0.01)、D-二聚体(MD=0.23,P<0.01)、APACHE-Ⅱ评分(MD=2.47,P<0.01)、Ranson评分(MD=1.60,P<0.01)和坏死范围≥30%(OR=2.52,P<0.01)(表5)。结果表明,BMI、CRP、PCT、D-二聚体和坏死范围≥30%仅在东方国家有显著性差异,东方国家发生IPN的影响因素明显多于西方国家。对异质性高的东西方IPN的影响因素进行敏感性分析显示:在西方,器官衰竭结果不稳定;在东方,APACHE-Ⅱ评分结果稳定,CRP、SAP、坏死范围≥30%的结果不稳定。在分别去除Shen等[60]、Chen等[63]和Cao等[66]的研究之后,CRP(SMD=0.30,95%CI:0.11~0.48;I2=42%,P异质性=0.16)、SAP(OR=15.20,95%CI:10.38~22.25;I2=0,P异质性=0.32)和坏死范围≥30%(OR=3.55,95%CI:2.52~5.00;I2=27%,P异质性=0.24)的异质性显著降低。进一步以IPN和SPN分组,探讨器官衰竭影响因素的异质性来源。结果显示器官衰竭(OR=2.63,95%CI:0.59~11.80;I2=80%,P异质性=0.006)不能区分IPN和SPN,且敏感性分析结果稳定。

2.4 发表偏倚 发表偏倚采用进行漏斗图进行识别,结果显示:年龄、性别、酒精性病因、胆源性病因、APACHE-Ⅱ评分和Ranson评分的漏斗图均表现为左右对称分布,表明本研究结果无明显发表偏倚。

3 讨论

本研究结果显示在整体人群中,ANP的影响因素及IPN的影响因素与既往研究基本一致[27,47,62,65]。ANP的影響因素:在东方,得到强有力证据支持的是D-二聚体、胆源性病因和酒精性病因;中度证据支持的是男性和CRP;边缘证据支持的是APACHE-Ⅱ评分。在西方,强有力证据支持的是器官衰竭;中度证据支持的是男性;弱证据支持的是CRP、APACHE-Ⅱ评分和Ranson评分。IPN的影响因素:在东方,得到强有力证据支持的是年龄、CRP、BMI、PCT、D-二聚体和坏死范围≥30%;弱证据支持的是Ranson评分;边缘证据支持的是白蛋白和APACHE-Ⅱ评分。在西方,强有力证据支持的是年龄和SIRS;中度证据支持的是酒精病因;弱证据支持的是Ranson评分和器官衰竭;边缘证据支持的是APACHE-Ⅱ评分。

整体及东西方ANP各人群共同的影响因素有:(1)男性,其原因之一是男性患者喜饮酒[35],酒精加重了胰腺负担;其二是男性体质属阳易化热,女性属阴易化寒,而AP多属湿热证,考虑到清热的柴芩承气汤能改善胰腺微循环[71],推测湿热的男性体质易发生微循环障碍。(2)CRP,CRP能预测ANP的发生,此研究结果与以往研究[36]一致。(3)APACHE-Ⅱ评分,由于其复杂性,很少在普通病房使用。东西方人群存在区别的影响因素:(1)胆源性病因是东方人群胰腺坏死的保护因素,此研究结果与姜丹等[72]研究一致。胆源性胰腺炎与其他类型胰腺炎在发病机制上有所差异,其与胆汁酸引起的钙离子超载、活性氧生成增加、线粒体功能损伤有关[73]。此外,早期ERCP手术的开展减轻了胆源性胰腺炎患者病情的严重程度。而在国外,胆道问题处理时机相对较晚[74],这可能是胆源性病因不是西方人群的保护因素的原因;(2)酒精性病因是整体及东方人群的影响因素,东方人群长期饮酒使胰腺更易发生坏死。原因可能是由于饮酒类型[75]、人群对酒精敏感性[76]以及环境或遗传因素的不同[75]。亚洲人的AP与酒精脱氢酶-2和醛脱氢酶-2的多态性有关,而未发现白人的AP与此相关[76]。酒精影响胰腺细胞死亡反应的机制有多种。乙醇分解为脂肪酸乙醇酯可以改变细胞的钙离子传递,导致线粒体功能障碍和细胞坏死[77]。此外,乙醇还会影响胰腺实质细胞的炎症反应和死亡途径[77]。乙醇可以增强组织蛋白酶B的表达和活性,而组织蛋白酶B可能会增强坏死。同时,乙醇可能抑制胰腺实质中JAK2/STAT1信号通路,进而降低半胱天冬酶的活性和表达;(3)Ranson评分是整体和西方人群的影响因素,该评分系统需在患者入院48 h后使用,且有些指标并不常规采集(如剩余碱)。受研究数量影响,尚不能区分双方差异的指标有:(1)Cre,该指标反映了血管内容积和内脏血流[41]和微血管灌注[78];(2)吸烟可致与胰腺坏死有关肝外门静脉系统血栓形成的风险增加60%[79-80];(3)D-二聚体是ANP患者发生凝血紊乱和微循环障碍的中间产物;(4)器官衰竭,约45%的ANP患者会并发器官衰竭[81]。

整体及东西方IPN各人群共同的影响因素有:(1)年龄,老年人作为AP严重程度和死亡的风险因素已被广泛研究,因此被纳入如APACHE-Ⅱ评分、Ranson评分等评分系统中[82]。国外一项动物实验[83]亦证明与年轻组相比,老年组大鼠胰腺组织的阳性细菌培养明显增加;(2)CRP会在组织损伤、炎症反应和细菌感染时升高,具有高敏感性和低特异性[27];(3)APACHE-Ⅱ和Ranson评分,此结果与Papachristou等[84]的研究结果一致。东西方人群存在区别的影响因素:(1)BMI是东方人群的影响因素,这可能与东方人易患腹型肥胖有关[85]。脂肪分解产生的不饱和脂肪酸抑制了线粒体复合物Ⅰ和Ⅴ,导致胰腺坏死[85],加重AP的严重程度。另一种可能是,内脏肥胖患者的脂联素水平较低,导致炎症反应增大[86]。而肥胖患者更易感染,机制尚不清楚,可能是由于肥胖相关的免疫失调,降低了细胞介导的免疫应答;(2)坏死范围≥30%是东方和整体人群的影响因素。究其原因可能是,坏死面积越大,感染的机会越大;另一个原因是不同地区的人群肠道菌群不同。在AP期间,肠道微生物群失调导致短链脂肪酸减少,减少肠上皮细胞的增殖和分化,促进细胞凋亡,破坏肠屏障,导致细菌移位,这是IPN的主要原因[64]。东西方肠道菌群不同可能是导致IPN不同影响因素的根本原因;(3)酒精性病因是西方人群的保护因素,可能是酒精更大程度改变了西方人群的肠道菌群,肠道微生态及其代谢产物改变影响了患者肠道的通透性,但这有待进一步实验证明;(4)器官衰竭是西方人群的影响因素,其与患者免疫功能受损和异常有关,不同的人免疫功能不同,未来还可以进一步比较东西方人群在器官衰竭发生率上的差异,进一步更深层次的发现其本质差异,为未来研究靶点提供参考。因研究数量较少,尚不能区分双方差异的指标有:(1)低蛋白血症 患者体内丢失的白蛋白与游离脂肪酸结合,促进炎症反应进展和血管通透性增加[87]。此外,白蛋白水平是患者营养水平的衡量指标,充足的热量能转运出细胞内更多的钙离子,从而减少细胞的损伤[88]; (2)PCT在细菌或真菌感染和败血症时含量升高[19]。CRP联合PCT对IPN的预测价值值得探讨;(3)D-二聚体,在亚组分析中发现,D-二聚体并不是SPN进展为IPN的影响因素,出现此研究结果的原因可能是D-二聚体的产生发生在胰腺组织坏死时,而不是后期继发感染时; (4)SIRS评分,本研究结果提示其仅为西方人群IPN的影响因素;另有研究[89]表明将SIRS评分纳为条目的PASS评分能预测东方人群的IPN,故单独使用SIRS评分的价值仍需进一步研究。

本研究存在的不足:首先,本研究结果可能存在一些混杂因素导致结果偏差。其次,由于数据的限制,一些影响因素如钙、补体C3、血清甘油三酯等未纳入荟萃分析。此外,本研究中许多指标的异质性水平较高,异质性可能来源于不同的研究类型、人群或病因。因此,笔者通过亚组分析、选择合适的统计模型来降低异质性。今后仍需开展高质量、大规模、跨国的前瞻性研究进一步证明影响因素的差异。

结合纳入研究的数量及质量,综上所述,胆源性病因及酒精性病因是东方人群胰腺坏死特异性影响因素,Ranson评分是西方人群特异性影响因素;BMI和坏死范圍≥30%是东方人群IPN特异性影响因素,酒精性病因是西方人群IPN特异性影响因素。研究者可进一步分析造成东西方差异的原因,为疾病的发生、发展及治疗提供新视角。此外本研究进一步提示需根据人群特点构建出更适合的预测工具。

利益冲突声明:本文不存在任何利益冲突。

作者贡献声明:陈娟负责论文设计和拟定写作思路;马书丽、杨晓曦负责文献检索、整理并分析数据;马书丽负责解读数据并撰写论文初稿;陈晨指导分析数据,修改论文;喻静、周游、路国涛、向晓星、龚卫娟、陈炜炜指导撰写文章并最后定稿。

参考文献:

[1]

TAN C, YANG L, SHI F, et al. Early systemic inflammatory response syndrome duration predicts infected pancreatic necrosis[J]. J Gastrointest Surg, 2020, 24(3): 590-597. DOI: 10.1007/s11605-019-04149-5.

[2]MEDEROS MA, REBER HA, GIRGIS MD. Acute pancreatitis: A review[J]. JAMA, 2021, 325(4): 382-390. DOI: 10.1001/JAMA.2020.20317.

[3]BARON TH, DIMAIO CJ, WANG AY, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice Update: Management of pancreatic necrosis[J]. Gastroenterology, 2020, 158(1): 67-75.e1. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.064.

[4]DING L, YU C, DENG F, et al. New Risk factors for infected pancreatic necrosis secondary to severe acute pancreatitis: The role of initial contrast-enhanced computed tomography[J]. Dig Dis Sci, 2019, 64(2): 553-560. DOI: 10.1007/s10620-018-5359-y.

[5]TRIKUDANATHAN G, WOLBRINK D, van SANTVOORT HC, et al. Current concepts in severe acute and necrotizing pancreatitis: An evidence-based approach[J]. Gastroenterology, 2019, 156(7): 1994-2007.e3. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.269.

[6]MAK WY, ZHAO M, NG SC, et al. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: East meets west[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2020, 35(3): 380-389. DOI: 10.1111/jgh.14872.

[7]HOZO SP, DJULBEGOVIC B, HOZO I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample[J]. BMC Med Res Methodol, 2005, 5: 13. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13.

[8]WAN X, WANG W, LIU J, et al. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range[J]. BMC Med Res Methodol, 2014, 14: 135. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135.

[9]MAO J, ZHANG Q, ZHANG H, et al. Risk factors for lymph node metastasis in papillary thyroid carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2020, 11: 265. DOI: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00265.

[10]JI X, LENG XY, DONG Y, et al. Modifiable risk factors for carotid atherosclerosis: a meta-analysis and systematic review[J]. Ann Transl Med, 2019, 7(22): 632. DOI: 10.21037/atm.2019.10.115.

[11]VAN DER VLIST AC, BREDA SJ, OEI E, et al. Clinical risk factors for Achilles tendinopathy: a systematic review[J]. Br J Sports Med, 2019, 53(21): 1352-1361. DOI: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099991.

[12]KUNZE KN, WRIGHT-CHISEM J, POLCE EM, et al. Risk factors for ramp lesions of the medial meniscus: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Am J Sports Med, 2021, 49(13): 3749-3757. DOI: 10.1177/0363546520986817.

[13]BCHLER M, MALFERTHEINER P, SCHOETENSACK C, et al. Sensitivity of antiproteases, complement factors and C-reactive protein in detecting pancreatic necrosis. Results of a prospective clinical study[J]. Int J Pancreatol, 1986, 1(3-4): 227-235. DOI: 10.1007/BF02795248.

[14]BCHLER M, MALFERTHEINER P, SCHDLICH H, et al. Prognostic value of serum phospholipase A in acute pancreatitis[J]. Klin Wochenschr, 1989, 67(3): 186-189. DOI: 10.1007/BF01711351.

[15]DOMSCHKE S, MALFERTHEINER P, UHL W, et al. Free fatty acids in serum of patients with acute necrotizing or edematous pancreatitis[J]. Int J Pancreatol, 1993, 13(2): 105-110. DOI: 10.1007/BF02786078.

[16]KAUFMANN P, TILZ GP, SMOLLE KH, et al. Increased plasma concentrations of circulating intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (cICAM-1) in patients with necrotizing pancreatitis[J]. Immunobiology, 1996, 195(2): 209-219. DOI: 10.1016/S0171-2985(96)80040-4.

[17]SCHMID SW, UHL W, STEINLE A, et al. Human pancreas-specific protein. A diagnostic and prognostic marker in acute pancreatitis and pancreas transplantation[J]. Int J Pancreatol, 1996, 19(3): 165-170. DOI: 10.1007/BF02787364.

[18]MANES G, SPADA OA, RABITTI PG, et al. Serum interleukin-6 in acute pancreatitis due to common bile duct stones. A reliable marker of necrosis[J]. Recenti Prog Med, 1997, 88(2): 69-72.

[19]RAU B, STEINBACH G, GANSAUGE F, et al. The potential role of procalcitonin and interleukin 8 in the prediction of infected necrosis in acute pancreatitis[J]. Gut, 1997, 41(6): 832-840. DOI: 10.1136/gut.41.6.832.

[20]TENNER S, SICA G, HUGHES M, et al. Relationship of necrosis to organ failure in severe acute pancreatitis[J]. Gastroenterology, 1997, 113(3): 899-903. DOI: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70185-9.

[21]BAILLARGEON JD, ORAV J, RAMAGOPAL V, et al. Hemoconcentration as an early risk factor for necrotizing pancreatitis[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 1998, 93(11): 2130-2134. DOI: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00608.x.

[22]RAU B, CEBULLA M, UHL W, et al. The clinical value of human pancreas-specific protein procarboxypeptidase B as an indicator of necrosis in acute pancreatitis: comparison to CRP and LDH[J]. Pancreas, 1998, 17(2): 134-139. DOI: 10.1097/00006676-199808000-00004.

[23]HIETARANTA A, KEMPPAINEN E, PUOLAKKAINEN P, et al. Extracellular phospholipases A2 in relation to systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and systemic complications in severe acute pancreatitis[J]. Pancreas, 1999, 18(4): 385-391. DOI: 10.1097/00006676-199905000-00009.

[24]BROWN A, ORAV J, BANKS PA. Hemoconcentration is an early marker for organ failure and necrotizing pancreatitis[J]. Pancreas, 2000, 20(4): 367-372. DOI: 10.1097/00006676-200005000-00005.

[25]BUTTENSCHOEN K, BERGER D, HIKI N, et al. Endotoxin and antiendotoxin antibodies in patients with acute pancreatitis[J]. Eur J Surg, 2000, 166(6): 459-466. DOI: 10.1080/110241500750008772.

[26]MNDI Y, FARKAS G, TAKCS T, et al. Diagnostic relevance of procalcitonin, IL-6, and sICAM-1 in the prediction of infected necrosis in acute pancreatitis[J]. Int J Pancreatol, 2000, 28(1): 41-49. DOI: 10.1385/IJGC:28:1:41.

[27]MLLER CA, UHL W, PRINTZEN G, et al. Role of procalcitonin and granulocyte colony stimulating factor in the early prediction of infected necrosis in severe acute pancreatitis[J]. Gut, 2000, 46(2): 233-238. DOI: 10.1136/gut.46.2.233.

[28]RAU B, STEINBACH G, BAUMGART K, et al. Serum amyloid A versus C-reactive protein in acute pancreatitis: clinical value of an alternative acute-phase reactant[J]. Crit Care Med, 2000, 28(3): 736-742. DOI: 10.1097/00003246-200003000-00022.

[29]RAU B, STEINBACH G, BAUMGART K, et al. The clinical value of procalcitonin in the prediction of infected necrosis in acute pancreatitis[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2000, 26 (Suppl 2): S159-164. DOI: 10.1007/BF02900730.

[30]KHAN AA, PAREKH D, CHO Y, et al. Improved prediction of outcome in patients with severe acute pancreatitis by the APACHE II score at 48 hours after hospital admission compared with the APACHE II score at admission. Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation[J]. Arch Surg, 2002, 137(10): 1136-1140. DOI: 10.1001/archsurg.137.10.1136.

[31]MLLER CA, APPELROS S, UHL W, et al. Serum levels of procarboxypeptidase B and its activation peptide in patients with acute pancreatitis and non-pancreatic diseases[J]. Gut, 2002, 51(2): 229-235. DOI: 10.1136/gut.51.2.229.

[32]PEREZ A, WHANG EE, BROOKS DC, et al. Is severity of necrotizing pancreatitis increased in extended necrosis and infected necrosis?[J]. Pancreas, 2002, 25(3): 229-233. DOI: 10.1097/00006676-200210000-00003.

[33]RICH FC, CHOLLEY BP, LAISN MJ, et al. Inflammatory cytokines, C reactive protein, and procalcitonin as early predictors of necrosis infection in acute necrotizing pancreatitis[J]. Surgery, 2003, 133(3): 257-262. DOI: 10.1067/msy.2003.70.

[34]BARAUSKAS G, SVAGZDYS S, MALECKAS A. C-reactive protein in early prediction of pancreatic necrosis[J]. Medicina (Kaunas), 2004, 40(2): 135-140.

[35]PAPACHRISTOU GI, PAPACHRISTOU DJ, MORINVILLE VD, et al. Chronic alcohol consumption is a major risk factor for pancreatic necrosis in acute pancreatitis[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2006, 101(11): 2605-2610. DOI: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00795.x.

[36]DAMBRAUSKAS Z, GULBINAS A, PUNDZIUS J, et al. Value of routine clinical tests in predicting the development of infected pancreatic necrosis in severe acute pancreatitis[J]. Scand J Gastroenterol, 2007, 42(10): 1256-1264. DOI: 10.1080/00365520701391613.

[37]LPEZ A, de LA CUEVA L, MARTNEZ MJ, et al. Usefulness of technetium-99m hexamethylpropylene amine oxime-labeled leukocyte scintigraphy to detect pancreatic necrosis in patients with acute pancreatitis. Prospective comparison with Ranson, Glasgow and APACHE-II scores and serum C-reactive protein[J]. Pancreatology, 2007, 7(5-6): 470-478. DOI: 10.1159/000108964.

[38]MULLER CA, BELYAEV O, VOGESER M, et al. Corticosteroid-binding globulin: a possible early predictor of infection in acute necrotizing pancreatitis[J]. Scand J Gastroenterol, 2007, 42(11): 1354-1361. DOI: 10.1080/00365520701416691.

[39]RAHMAN SH, MENON KV, HOLMFIELD JH, et al. Serum macrophage migration inhibitory factor is an early marker of pancreatic necrosis in acute pancreatitis[J]. Ann Surg, 2007, 245(2): 282-289. DOI: 10.1097/01.sla.0000245471.33987.4b.

[40]de CAMPOS T, CERQUEIRA C, KURYURA L, et al. Morbimortality indicators in severe acute pancreatitis[J]. JOP, 2008, 9(6): 690-697.

[41]MUDDANA V, WHITCOMB DC, KHALID A, et al. Elevated serum creatinine as a marker of pancreatic necrosis in acute pancreatitis[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2009, 104(1): 164-170. DOI: 10.1038/ajg.2008.66.

[42]LIPINSKI M, RYDZEWSKI A, RYDZEWSKA G. Early changes in serum creatinine level and estimated glomerular filtration rate predict pancreatic necrosis and mortality in acute pancreatitis: Creatinine and eGFR in acute pancreatitis[J]. Pancreatology, 2013, 13(3): 207-211. DOI: 10.1016/j.pan.2013.02.002.

[43]TALUKDAR R, NECHUTOVA H, CLEMENS M, et al. Could rising BUN predict the future development of infected pancreatic necrosis?[J]. Pancreatology, 2013, 13(4): 355-359. DOI: 10.1016/j.pan.2013.05.003.

[44]KOSTIC I, SPASIC M, STOJANOVIC B, et al. Early cytokine profile changes in interstitial and necrotic forms of acute pancreatitis[J]. Serb J Exp Clin Res, 2015, 16(1): 33-37. DOI: 10.1515/sjecr-2015-0005.

[45]EASLER JJ, DE-MADARIA E, NAWAZ H, et al. Patients with sentinel acute pancreatitis of alcoholic etiology are at risk for organ failure and pancreatic necrosis: A dual-center experience[J]. Pancreas, 2016, 45(7): 997-1002. DOI: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000643.

[46]MORAN RA, JALALY NY, KAMAL A, et al. Ileus is a predictor of local infection in patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis[J]. Pancreatology, 2016, 16(6): 966-972. DOI: 10.1016/j.pan.2016.10.002.

[47]GARRET C, PRON M, REIGNIER J, et al. Risk factors and outcomes of infected pancreatic necrosis: Retrospective cohort of 148 patients admitted to the ICU for acute pancreatitis[J]. United European Gastroenterol J, 2018, 6(6): 910-918. DOI: 10.1177/2050640618764049.

[48]VERDONK RC, STERNBY H, DIMOVA A, et al. Short article: Presence, extent and location of pancreatic necrosis are independent of aetiology in acute pancreatitis[J]. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2018, 30(3): 342-345. DOI: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001053.

[49]SZAKCS Z, GEDE N, PCSI D, et al. Aging and comorbidities in acute pancreatitis II.: A cohort-analysis of 1203 prospectively collected cases[J]. Front Physiol, 2018, 9: 1776. DOI: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01776.

[50]ISOGAI M, YAMAGUCHI A, HORI A, et al. LDH to AST ratio in biliary pancreatitis-a possible indicator of pancreatic necrosis: preliminary results[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 1998, 93(3): 363-367. DOI: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00363.x.

[51]METTU SR, WIG JD, KHULLAR M, et al. Efficacy of serum nitric oxide level estimation in assessing the severity of necrotizing pancreatitis[J]. Pancreatology, 2003, 3(6): 506-513; discussion 513-514. DOI: 10.1159/000076021.

[52]GARG PK, MADAN K, PANDE GK, et al. Association of extent and infection of pancreatic necrosis with organ failure and death in acute necrotizing pancreatitis[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2005, 3(2): 159-166. DOI: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00665-2.

[53]GARDNER TB, OLENEC CA, CHERTOFF JD, et al. Hemoconcentration and pancreatic necrosis: further defining the relationship[J]. Pancreas, 2006, 33(2): 169-173. DOI: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000226885.32957.17.

[54]UEDA T, TAKEYAMA Y, YASUDA T, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase-to-lymphocyte ratio for the prediction of infection in acute necrotizing pancreatitis[J]. Pancreas, 2007, 35(4): 378-380. DOI: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000297827.05678.9e.

[55]GUO J, XUE P, YANG XN, et al. Serum matrix metalloproteinase-9 is an early marker of pancreatic necrosis in patients with severe acute pancreatitis[J]. Hepatogastroenterology, 2012, 59(117): 1594-1598. DOI: 10.5754/hge11563.

[56]KE L, NI HB, TONG ZH, et al. D-dimer as a marker of severity in patients with severe acute pancreatitis[J]. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci, 2012, 19(3): 259-265. DOI: 10.1007/s00534-011-0414-5.

[57]LU Z, LIU Y, DONG YH, et al. Soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells in severe acute pancreatitis: a biological marker of infected necrosis[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2012, 38(1): 69-75. DOI: 10.1007/s00134-011-2369-z.

[58]GUO Q, LI A, XIA Q, et al. The role of organ failure and infection in necrotizing pancreatitis: a prospective study[J]. Ann Surg, 2014, 259(6): 1201-1207. DOI: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000264.

[59]ERBIS H, ALIOSMANOGLU I, TURKOGLU MA, et al. Evaluating mean platelet volume as a new indicator for confirming the diagnosis of necrotizing pancreatitis[J]. Ann Ital Chir, 2015, 86(2): 132-136.

[60]SHEN X, SUN J, KE L, et al. Reduced lymphocyte count as an early marker for predicting infected pancreatic necrosis[J]. BMC Gastroenterol, 2015, 15: 147. DOI: 10.1186/s12876-015-0375-2.

[61]THANDASSERY RB, YADAV TD, DUTTA U, et al. Hypotension in the first week of acute pancreatitis and APACHE II score predict development of infected pancreatic necrosis[J]. Dig Dis Sci, 2015, 60(2): 537-542. DOI: 10.1007/s10620-014-3081-y.

[62]JI L, LV JC, SONG ZF, et al. Risk factors of infected pancreatic necrosis secondary to severe acute pancreatitis[J]. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int, 2016, 15(4): 428-433. DOI: 10.1016/s1499-3872(15)60043-1.

[63]CHEN HZ, JI L, LI L, et al. Early prediction of infected pancreatic necrosis secondary to necrotizing pancreatitis[J]. Medicine (Baltimore), 2017, 96(30): e7487. DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007487.

[64]CHEN Y, KE L, MENG L, et al. Endothelial markers are associated with pancreatic necrosis and overall prognosis in acute pancreatitis: A preliminary cohort study[J]. Pancreatology, 2017, 17(1): 45-50. DOI: 10.1016/j.pan.2016.12.005.

[65]ZHANG Y, GUO F, LI S, et al. Decreased high density lipoprotein cholesterol is an independent predictor for persistent organ failure, pancreatic necrosis and mortality in acute pancreatitis[J]. Sci Rep, 2017, 7(1): 8064. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-017-06618-w.

[66]CAO X, WANG HM, DU H, et al. Early predictors of hyperlipidemic acute pancreatitis[J]. Exp Ther Med, 2018, 16(5): 4232-4238. DOI: 10.3892/etm.2018.6713.

[67]NODA Y, GOSHIMA S, FUJIMOTO K, et al. Utility of the portal venous phase for diagnosing pancreatic necrosis in acute pancreatitis using the CT severity index[J]. Abdom Radiol (NY), 2018, 43(11): 3035-3042. DOI: 10.1007/s00261-018-1579-z.

[68]NAL Y, BARLAS AM. Role of increased immature granulocyte percentage in the early prediction of acute necrotizing pancreatitis[J]. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg, 2019, 25(2): 177-182. DOI: 10.14744/tjtes.2019.70679.

[69]WAN J, YANG X, HE W, et al. Serum D-dimer levels at admission for prediction of outcomes in acute pancreatitis[J]. BMC Gastroenterol, 2019, 19(1): 67. DOI: 10.1186/s12876-019-0989-x.

[70]CAMPBELL C, WANG T, MCNAUGHTON AL, et al. Risk factors for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. J Viral Hepat, 2021, 28(3): 493-507. DOI: 10.1111/jvh.13452.

[71]QIN SH, TANG YM, LI Q,et al. Clinical efficacy and mechanism of Chaishao Chengqi Decoction in the treatment of acute pancreatitis [J]. Hunan J Tradit Chin Med, 2022, 38(6): 197-201. DOI: 10.16808/j.cnki.issn1003-7705.2022.06.046.

覃樹辉, 唐友明, 黎锵, 等. 柴芍承气汤治疗急性胰腺炎的临床疗效及作用机制研究进展[J]. 湖南中医杂志, 2022, 38(6): 197-201. DOI: 10.16808/j.cnki.issn1003-7705.2022.06.046.

[72]JIANG D, LUO BW, LIANG ZH, et al. A preliminary study on the data model construction for predicting pancreatic necrosis in acute pancreatitis [J]. J Guangxi Med Univ, 2022, 39(7): 1106-1111. DOI: 10.16190/j.cnki.45-1211/r.2022.07.013.

姜丹, 罗博文, 梁志海, 等. 预测急性胰腺炎发生胰腺坏死的数据模型建立的初步研究[J].广西医科大学学报, 2022, 39(7): 1106-1111. DOI: 10.16190/j.cnki.45-1211/r.2022.07.013.

[73]FANCZAL J, PALLAGI P, GRG M, et al. TRPM2-mediated extracellular Ca2+ entry promotes acinar cell necrosis in biliary acute pancreatitis[J]. J Physiol, 2020, 598(6): 1253-1270. DOI: 10.1113/JP279047.

[74]HALLENSLEBEN ND, TIMMERHUIS HC, HOLLEMANS RA, et al. Optimal timing of cholecystectomy after necrotising biliary pancreatitis[J]. Gut, 2022, 71(5): 974-982. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324239.

[75]YADAV D, LOWENFELS AB. The epidemiology of pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer[J]. Gastroenterology, 2013, 144(6): 1252-1261. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.068.

[76]YADAV D, PAPACHRISTOU GI, WHITCOMB DC. Alcohol-associated pancreatitis[J]. Gastroenterol Clin North Am, 2007, 36(2): 219-238, vii. DOI: 10.1016/j.gtc.2007.03.005.

[77]PANDOL SJ, RARATY M. Pathobiology of alcoholic pancreatitis[J]. Pancreatology, 2007, 7(2-3): 105-114. DOI: 10.1159/000104235.

[78]CUTHBERTSON CM, CHRISTOPHI C. Disturbances of the microcirculation in acute pancreatitis[J]. Br J Surg, 2006, 93(5): 518-530. DOI: 10.1002/bjs.5316.

[79]REBOURS V, BOUDAOUD L, VULLIERME MP, et al. Extrahepatic portal venous system thrombosis in recurrent acute and chronic alcoholic pancreatitis is caused by local inflammation and not thrombophilia[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2012, 107(10): 1579-1585. DOI: 10.1038/ajg.2012.231.

[80]EASLER J, MUDDANA V, FURLAN A, et al. Portosplenomesenteric venous thrombosis in patients with acute pancreatitis is associated with pancreatic necrosis and usually has a benign course[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2014, 12(5): 854-862. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.068.

[81]SCHEPERS NJ, BAKKER OJ, BESSELINK MG, et al. Impact of characteristics of organ failure and infected necrosis on mortality in necrotising pancreatitis[J]. Gut, 2019, 68(6): 1044-1051. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314657.

[82]MORAN RA, GARCA-RAYADO G, DE LA IGLESIA-GARCA D, et al. Influence of age, body mass index and comorbidity on major outcomes in acute pancreatitis, a prospective nation-wide multicentre study[J]. United European Gastroenterol J, 2018, 6(10): 1508-1518. DOI: 10.1177/2050640618798155.

[83]COELHO A, MACHADO M, SAMPIETRE SN, et al. Local and systemic effects of aging on acute pancreatitis[J]. Pancreatology, 2019, 19(5): 638-645. DOI: 10.1016/j.pan.2019.06.005.

[84]PAPACHRISTOU GI, MUDDANA V, YADAV D, et al. Comparison of BISAP, Ransons, APACHE-II, and CTSI scores in predicting organ failure, complications, and mortality in acute pancreatitis[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2010, 105(2): 435-441; quiz 442. DOI: 10.1038/ajg.2009.622.

[85]KHATUA B, EL-KURDI B, SINGH VP. Obesity and pancreatitis[J]. Curr Opin Gastroenterol, 2017, 33(5): 374-382. DOI: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000386.

[86]NATU A, STEVENS T, KANG L, et al. Visceral adiposity predicts severity of acute pancreatitis[J]. Pancreas, 2017, 46(6): 776-781. DOI: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000845.

[87]CHEN L, HUANG Y, YU H, et al. The association of parameters of body composition and laboratory markers with the severity of hypertriglyceridemia-induced pancreatitis[J]. Lipids Health Dis, 2021, 20(1): 9. DOI: 10.1186/s12944-021-01443-7.

[88]YAO Q, LIU P, PENG S, et al. Effects of immediate or early oral feeding on acute pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Pancreatology, 2022, 22(2): 175-184. DOI: 10.1016/j.pan.2021.11.009.

[89]KE L, MAO W, LI X, et al. The pancreatitis activity scoring system in predicting infection of pancreatic necrosis[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2018, 113(9): 1393-1394. DOI: 10.1038/s41395-018-0112-x.

收稿日期:

2022-03-18;錄用日期:2022-04-24

本文编辑:王亚南

引证本文:

MA SL, YANG XX, CHEN C, et al.

Influencing factors for acute necrotizing pancreatitis in Eastern and Western countries: A meta-analysis

[J]. J Clin Hepatol, 2023, 39(7): 1643-1656.

马书丽, 杨晓曦, 陈晨, 等.

东西方国家急性坏死性胰腺炎影响因素的Meta分析

[J]. 临床肝胆病杂志, 2023, 39(7): 1643-1656.