Best therapy for the easiest to treat hepatitis C virus genotype 1b-infected patients

2022-12-09DorotaZarebskaMichalukMichalBrzdekJerzyJaroszewiczMagdalenaTudrujekZdunekBeataLorencJakubKlapaczynskiWlodzimierzMazurAdamKazekMarekSitkoHannaBerakJustynaJanochaLitwinDorotaDybowskatukaszSupronowiczRafatKrygierJolantaCitkoA

Dorota Zarebska-Michaluk,Michal Brzdek,Jerzy Jaroszewicz,Magdalena Tudrujek-Zdunek, Beata Lorenc,Jakub Klapaczynski,Wlodzimierz Mazur, Adam Kazek,Marek Sitko, Hanna Berak, Justyna Janocha-Litwin,Dorota Dybowska, tukasz Supronowicz, Rafat Krygier, Jolanta Citko, Anna Piekarska,Robert Flisiak

Abstract

Key Words: Hepatitis C; Genotype 1b; Direct-acting antivirals; Pangenotypic; Genotype-specific; Sustained virologic response

INTRODUCTION

The revolution in antiviral treatment of chronic infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) dates to 2011 when direct-acting antivirals (DAA) were introduced into therapeutic regimens. The first registered drugs in this group were used in combination with an existing regimen containing pegylated interferon(pegIFN) and ribavirin (RBV) and their activity was limited to HCV genotype (GT) 1 infections[1].Evaluated in the retrospect, it seems that it is patients infected with HCV GT1 who have become the beneficiaries of this therapeutic revolution.

GT1 infections are nearly equally divided into subtypes 1a and 1b, are the most common worldwide accounting for about 49% of all cases of chronic hepatitis C (CHC), which, according to the latest data, is estimated at 58 million people[2-4]. With the highest global prevalence, GT1 infection is the leading cause of the most severe complications of CHC, such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the chronically HCV-infected population. It was therefore of great public health importance that GT1-infected patients were also the first to gain access to highly effective and safe IFN-free regimens, termed GT-specific due to their activity against GT1 and GT4 only[5]. As a result, the treatment efficacy of GT1-infected patients increased to 95% and above compared to the approximately 50% efficacy of pegIFN +RBV therapy[6]. It is additionally worth noting that pegIFN + RBV therapy was less effective against HCV subtype 1b than subtype 1a, and this difference was independent of other factors that may favor viral clearance[7]. At the same time, for patients with GT3 infection, the second most common HCVinfected population with the share of 18%, the only IFN-free regimen available was a combination of sofosbuvir (SOF) + RBV with a suboptimal efficacy of 75% comparable to that achieved with pegIFN +RBV therapy[5,6]. In this way the population of GT1-infected individuals defined as “difficult to treat”in the IFN era became “easy to treat” in the time of DAA therapies. And conversely to what happened in the IFN era among patients with GT1 infection, the best treatment results with DAA were obtained in those infected with subtype 1b, who can therefore be called the “easiest to treat”. This is due to resistance associated substitutions with the potential to reduce efficacy which are more common in the subtype 1a[8].

The differences in the treatment efficacy between GT1 and GT3-infected patients have balanced out with the registration of pangenotypic regimens with documented activity against all HCV GTs[9,10].The purpose of this analysis was to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of antiviral treatment in patients with GT1b infection from real-world experience (RWE) settings since the beginning of the IFNfree era with the identification of the most effective type of therapy and to identify positive and negative predictors that affect the likelihood of virological response in this “easiest to treat” but most numerous populations among HCV-infected patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

Patients chronically infected with GT1b HCV, whose data were obtained from the EpiTer-2 database,were included in this analysis. EpiTer-2 is an ongoing real-world multicenter observational project evaluating antiviral treatment of CHC since the beginning of the availability of IFN-free therapy in Poland. From mid-2015 to the end of 2021, 15156 patients in 22 Polish hepatology centers started DAA therapy and their data were retrospectively entered into an online questionnaire administered by TIBA.The study is supported by the Polish Association of Epidemiologists and Infectiologists.

The choice of the IFN-free regimen by the treating physician, as well as the monitoring of treatment,were guided by the recommendations of the Polish Group of Experts of HCV and the regulations on drug reimbursement under the drug program of the National Health Fund. Patients provided informed consent for treatment and the processing of personal data as required by the therapeutic program and national regulations[11,12]. Due to the observational, non-interventional nature of the study using approved drugs, ethics committee approval was waived in accordance with local law (Pharmaceutical Law of 6thSeptember 2001, art. 37al).

The database includes patients’ data, such as sex, age, body mass index (BMI), HCV GT, liver disease severity, current DAA regimen, history of previous therapy, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and HBV co-infection, comorbidities and comedications, and baseline laboratory test results, including aminotransferases activity, international normalized ratio, complete blood count, bilirubin, albumin and creatinine concentration.

Liver disease severity

Assessment of liver disease advancement included measurement of liver stiffness using non-invasive elastography with Fibroscan or Aixplorer with correlating METAVIR fibrosis values[13]. Patients with a fibrosis value of F4 were evaluated for the presence of esophageal varices, decompensation of liver function in the past and at the start of antiviral therapy and were assessed on the Child-Pugh scale. Data were also collected on the diagnosis of HCC and past liver transplantation.

Antiviral treatment

GT-specific regimens include asunaprevir (ASV) + daclatasvir (DCV), ledipasvir (LDV)/SOF ± RBV,ombitasvir (OBV)/paritaprevir (PTV)/ritonavir + dasabuvir (r + DSV) ± RBV, grazoprevir (GZR)/elbasvir (EBR) ± RBV, and others which included SOF, DCV, simeprevir used in various combination with or without RBV. Pangenotypic regimens include the combination of SOF and velpatasvir (VEL),voxilaprevir (VOX) with SOF/VEL, glecaprevir (GLE) and pibrentasvir (PIB), and GLE/PIB plus SOF and RBV.

Treatment effectiveness

Data on HCV RNA measured by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction with a lower limit of detection 10 IU/mL assessed at baseline, at the end of therapy and 12 wk after the treatment completion were collected. Based on these, the effectiveness of the treatment which is a sustained virological response (SVR), is determined and defined as undetectable HCV RNA 12 wk after the end of therapy.Patients lost to follow-up without HCV RNA evaluation 12 wk after the end of therapy were considered non-virological failures, while those with detectable viral load at this time point were considered virological failures.

Treatment safety

During therapy and up to 12 wk after its completion, data were collected on the treatment course,incidence of adverse events (AEs) with an assessment of their severity, and deaths with an assessment of their relation to antiviral therapy.

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as mean ± SD orn(%).Pvalues of < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. The significance of difference was calculated by Fisher’s exact or chi square tests for nominal variables and by Mann-WhitneyUtest for continuous and ordinal variables. Forward stepwise logistic regression models with Bayesian Information Criterion as a model selection criterion were performed with virological response as the dependent variable. Baseline independent variables were selected by significance in univariate analyses and included sex, fibrosis advancement, coinfection with HIV, liver cirrhosis decompensation at baseline, the history of cirrhosis decompensation, HCC, therapy, BMI,serum albumins, bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and platelets. Logistic regression models were calculated by use of Statistica 13.0 (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA, United States).

RESULTS

Patients’ characteristics

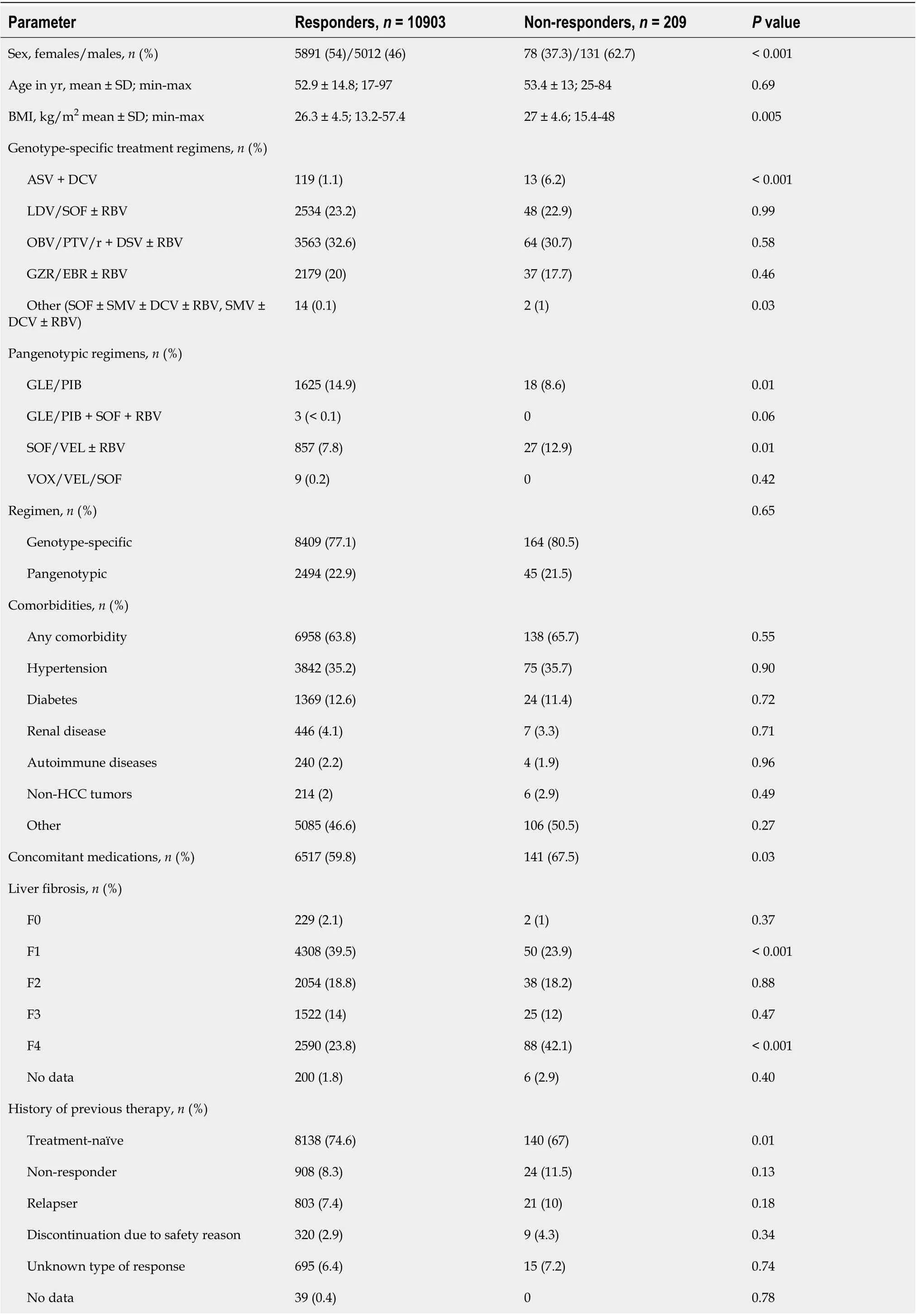

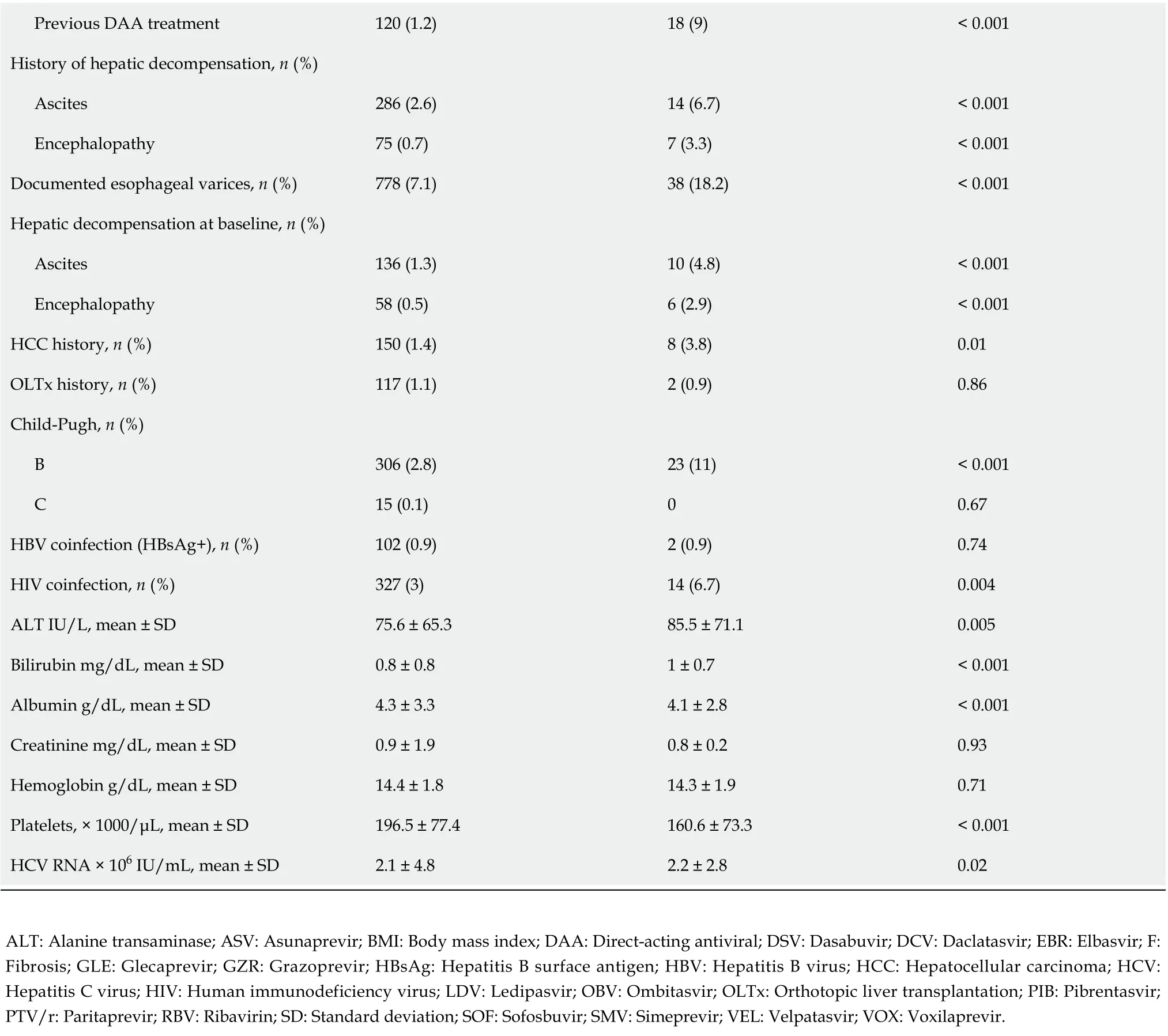

The population consisted of 11385 GT1b-infected patients with a mean age of 53 ± 14.8 years and a female predominance (53.4%). Detailed characteristics of patients are presented in Table 1. The majority of them had comorbidities with the most prevalent arterial hypertension (35.2%) followed by diabetes(12.7%), 60.1% were under pharmacological treatment for coexisting diseases. The largest group in terms of fibrosis was F1 patients who accounted for 39% of the analyzed population, patients with F4 corresponding to cirrhosis accounted for nearly a quarter of the cohort. The majority of them were compensated, 13.1% were scored as B and 0.1% as C in CP scale (Table 2). Hepatic decompensation at baseline in the form of ascites and encephalopathy was reported in 5.9% and 0.3% of them, respectively.Eight hundred and sixty (31%) patients had documented esophageal varices.

Antiviral treatment

Three-quarters of the studied patient population was treatment-naive; among those who had been previously treated, nonresponse was the most common type of treatment failure (Table 3). The most frequently used prior regimen was the combination of pegIFN + RBV, 155 patients (1.4%) were unsuccessfully treated with IFN-free options. Of the currently used regimens, 76.9% were GT-specific,with OBV/PTV/r + DSV ± RBV being the most commonly used option (32.4%). The GLE/PIB combination was the most frequently administered (14.8%) among the pangenotypic therapies. Twelvepatients were treated with triple pangenotypic regimens, three with GLE/PIB + SOF + RBV and nine with VOX/VEL/SOF, and all of them responded to treatment. In all cases, it was a rescue therapy used after prior DAA failure.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of 11385 genotype 1b-infected patients treated with interferon-free regimens

Treatment effectiveness

A total of 10903 patients responded to antiviral treatment, resulting in a 98.1% cure rate in the per protocol (PP) analysis after excluding 273 patients without SVR data. The effectiveness of different treatment regimens varied; in the PP analysis, the lowest 90.2% was reported for the GT-specific ASV +DCV regimen, while the highest effectiveness of 98.9% was achieved in the group of patients treated with GLE/PIB pangenotypic option (Table 4, Figure 1). The significantly higher percentage of men,patients with higher BMI, HIV co-infection and those taking concomitant medications were reported in virologic non- responders compared to patients with SVR (Table 5).

Table 2 Genotype 1b-infected patients with liver cirrhosis treated with direct-acting antivirals

This population also documented a lower proportion of patients with F1 fibrosis and a higher proportion of those with F4 fibrosis, patients with a history of decompensated liver function, as well as those with the presence of esophageal varices and decompensation at baseline. Statistically significant differences were also documented for laboratory test results consistent with advanced liver disease such as platelet count, bilirubin and albumin levels.

Virologic responders were more likely to be treatment-naive and significantly more frequently received the GLE/PIB regimen, while the proportion of ASV + DCV and SOF/VEL ± RBV were lower.There was no statistically significant difference in SVR by type of therapy, GT-specificvspangenotypic.Logistic regression analyses showed that virologic response in GT1b-infected patients was independently associated with female sex [odds ratio (OR) = 1.67], absence of cirrhosis decompensation at baseline (OR = 2.42) and higher baseline platelets (OR = 1.004 per 1000/μL increase), while the presence of HIV coinfection significantly decreased the odds of response (OR = 0.39) (Table 6).Importantly, there was no association with liver fibrosis, history of prior therapy, BMI or serum ALT,albumin and bilirubin levels.

Treatment safety

Regardless of the drug regimen used, the vast majority of patients (95.3%-100%) completed therapy as planned (Table 7). At least one AE occurred in 10.9%-36.3% of patients, with the highest percentage in those treated with ASV + DCV. This population also experienced the highest rate of serious AEs (SAEs)and discontinuation of therapy due to AEs, 5.2% and 1.5%, respectively. Among 7 SAEs reported during ASV + DCV therapy, two events were described as a transient elevation of aminotransferases activity;the remaining SAEs were not related to liver disease and antiviral therapy. In one person with elevated aminotransferases activity, the ASV + DCV was discontinued for this reason at week 20thbut finally this patient achieved an SVR. There were 64 deaths in the entire study population, none of which were judged by the treating physician to be related to antiviral treatment.

DISCUSSION

In our work, we analyzed a sizeable real-world population of patients infected with GT1b which is the most common HCV GT in Europe and in Poland accounts for about 82% of all cases of CHC[2,14].Dominating among HCV-infected patients, GT1b is also mainly responsible for the most severe complications of the disease, thus posing a public health burden which is why this population came under our attention.

We followed a cohort of 11385 patients from the beginning of the IFN-free era to the final stage which was the introduction of pangenotypic therapies using the retrospective national multicenter EpiTer-2 database. DAA therapy was effective in 98% of the analyzed population demonstrating what a hugeleap in treatment effectiveness has made in these patients compared to the IFN era when SVR was around 50%. Such a result supports our thesis that this is currently the easiest way to treat the HCVinfected population and is in line with the results of many RWE analyses on populations with GT1 infection[15,16]. However, it should be noted, that there are several papers that concentrate exclusively on GT1b-infected patients, and furthermore, some of them analyze only a specific DAA regimen[17-21].Focusing on patients with GT1b infection with the inclusion of all registered treatment regimens since the beginning of the DAA era in the analysis makes our study unique.

Table 3 Treatment characteristics of genotype 1b-infected patients treated with direct-acting antiviral

Regardless of which therapeutic options patients were treated with, effectiveness exceeded 90% and was higher than 98% for most regimens. The lowest SVR rate was documented for the GT-specific ASV+ DCV regimen which was the DAA option registered only for patients with GT1b infection and available in Poland until 2018. However, it should be noted that the effectiveness of 90.2% we achieved in Polish GT1b-infected patients using this therapeutic option was higher than the SVR of 85%documented in a meta-analysis in nine clinical trials[22].

The highest success rate among widely used regimens of 98.9% was achieved in patients treated with the pangenotypic option, GLE/PIB. Univariate analysis confirmed a significantly higher proportion of patients treated with this regimen among responders compared to virologic failures (P= 0.01). Our findings regarding the very high effectiveness of GLE/PIB are consistent with the results of many RWE analyses and clinical trials documenting efficacy of this regimen at 99%-100%[23-25]. Despite the disparity between the two regimens discussed above, we did not show a statistically significant difference in SVR overall between GT-specific and pangenotypic options. This finding is consistent withthe results of another Polish RWE analysis evaluating GT-specificvspangenotypic regimens in GT1binfected patients and according to our best knowledge there are no other analyses of a comparative nature[18]. We are aware that our study does not compare the two types of regimens head-to-head, it is a retrospective analysis and the results of comparison in this area should be approached with caution.However, considering the clinical trials and RWE studies evaluating the effects of therapy in GT1binfected patients with particular therapeutic regimens, belonging to both GT-specific and pangenotypic options, it should be concluded that our results are comparable to them. The largest group in our analysis were patients treated with the OBV/PTV/r + DSV ± RBV regimen, the first available DAA option in our country[26]. This means that it was used in patients at the beginning of the IFN-free era.Based on our previous study on the change in profile of patients in EpiTer-2 database, we can assume that they were older, more likely to have been diagnosed with cirrhosis, treatment-experienced, and had a greater burden of comorbidities, that is, more difficult to treat, compared to patients further down the DAA availability timeline[27]. The excellent 98.2% effectiveness of this regimen demonstrated by us supports the findings of numerous clinical trials and RWE analyses carried out in GT1b-infected patients[15-17,28,29]. We demonstrated in patients treated with LDV/SOF ± RBV, almost identical effectiveness. Based on the clinical trial results, this combination could be used even in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis[30]. Other RWE studies reported lower effectiveness of LDV/SOF ± RBV at the level of 93%-96% compared to 98.1% achieved in the current analysis but this difference may be related to baseline patient characteristics[15,31,32]. The list of GT-specific options in our study is completed by the GZR/EBR combination, the last regimen from this group in terms of timeline availability, with the excellent SVR of 98.3%. This is almost the same effectiveness as documented in a meta-analysis of eight randomized clinical trials with GZR/EBR[33]. Patients infected with GT1b achieved an SVR of 98.4 while those with GT1a infection responded 95.7% supporting the statement of the easiest to treat HCV population. A slightly lower success rate of 97.3% was reported in the cohort of United States veterans treated with GZR/EBR, while Korean patients responded at a rate of 98.6%,comparable to our analysis[21,34].

Table 4 The overall treatment effectiveness and according to treatment regimens in relation to different risk factors among the studied patients (per protocol analysis)

Among the currently available regimens for GT1b-infected patients, we documented the lowest SVR of 96.9% for the pangenotypic option SOF/VEL ± RBV. This combination is registered for use in any stage of liver disease including patients with decompensated cirrhosis which may have influenced our results[35]. In addition, we did not separately analyze the regimen without and with RBV which could also have affected the total result obtained[35,36].

Table 5 The comparison of virological responders and non-responders to direct-acting antiviral therapy

Previous DAA treatment 120 (1.2)18 (9)< 0.001 History of hepatic decompensation, n (%)Ascites 286 (2.6)14 (6.7)< 0.001 Encephalopathy 75 (0.7)7 (3.3)< 0.001 Documented esophageal varices, n (%)778 (7.1)38 (18.2)< 0.001 Hepatic decompensation at baseline, n (%)Ascites 136 (1.3)10 (4.8)< 0.001 Encephalopathy 58 (0.5)6 (2.9)< 0.001 HCC history, n (%)150 (1.4)8 (3.8)0.01 OLTx history, n (%)117 (1.1)2 (0.9)0.86 Child-Pugh, n (%)B 306 (2.8)23 (11)< 0.001 C 15 (0.1)00.67 HBV coinfection (HBsAg+), n (%)102 (0.9)2 (0.9)0.74 HIV coinfection, n (%)327 (3)14 (6.7)0.004 ALT IU/L, mean ± SD 75.6 ± 65.385.5 ± 71.10.005 Bilirubin mg/dL, mean ± SD 0.8 ± 0.81 ± 0.7< 0.001 Albumin g/dL, mean ± SD 4.3 ± 3.34.1 ± 2.8< 0.001 Creatinine mg/dL, mean ± SD 0.9 ± 1.90.8 ± 0.20.93 Hemoglobin g/dL, mean ± SD 14.4 ± 1.814.3 ± 1.90.71 Platelets, × 1000/μL, mean ± SD 196.5 ± 77.4160.6 ± 73.3< 0.001 HCV RNA × 106 IU/mL, mean ± SD 2.1 ± 4.82.2 ± 2.80.02 ALT: Alanine transaminase; ASV: Asunaprevir; BMI: Body mass index; DAA: Direct-acting antiviral; DSV: Dasabuvir; DCV: Daclatasvir; EBR: Elbasvir; F:Fibrosis; GLE: Glecaprevir; GZR: Grazoprevir; HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV:Hepatitis C virus; HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus; LDV: Ledipasvir; OBV: Ombitasvir; OLTx: Orthotopic liver transplantation; PIB: Pibrentasvir;PTV/r: Paritaprevir; RBV: Ribavirin; SD: Standard deviation; SOF: Sofosbuvir; SMV: Simeprevir; VEL: Velpatasvir; VOX: Voxilaprevir.

Twelve patients in our analysis were treated with triple pangenotypic regimens, GLE/PIB + SOF +RBV (n= 3) and VOX/VEL/SOF (n= 9) with 100% effectiveness. In each case, it was a rescue therapy used after prior DAA failure according to the guidelines[11,12,37,38]. Recommendations for the use of both regimens in DAA non- responders are based on the results of clinical trials documenting efficacy of 96%-100% of GT1b-infected patients[39,40]. It should be noted, however, that the clinical studies involved a small group of DAA-experienced patients with GT1b infection treated with VOX/VEL/SOF,only 69 individuals participated in the POLARIS-1 and POLARIS-4 studies, and in the case of GLE/PIB+ SOF + RBV therapy it was only one patient participating in the MAGELLAN-3 study. While RWE publications with a much larger number of patients and such characteristics confirming the high effectiveness of the VOX/VEL/SOF regimen are numerous, for the GLE/PIB + SOF + RBV option, data from routine clinical practice concern only two patients who responded to treatment[41-43].

Along with the very high effectiveness of DAA regimens in GT1b-infected patients, we documented a good safety profile supporting literature data[44]. Regardless of the option used, the vast majority of patients completed therapy as planned and discontinuation of treatment course due to AEs was experienced by a maximum of 1.5% of patients in the ASV + DCV group. In this population, we also noted the highest rate of serious AEs, 5.2%, in two patients in the form of transient elevation of aminotransferases, a phenomenon of unknown pathogenesis previously reported by researchers[45].None of the 64 deaths reported during therapy course and 12 wk of follow-up were considered by the treating physician to be related to antiviral treatment. The second objective of our analysis was to identify positive and negative predictors affecting the likelihood of virological response in GT1binfected patients.

Multivariate analysis showed that virologic response in GT1b-infected patients was independently associated with female sex, absence of cirrhosis decompensation at baseline and a higher platelet count,while the presence of HIV co-infection significantly reduced the odds of response. Moreover, no association with liver fibrosis, history of prior therapy, BMI or serum ALT levels, albumin and bilirubin concentration was documented.

Table 6 Factors associated with virologic response in logistic regression model in studied hepatitis C virus-genotype 1b population

It is difficult to directly compare our results to other studies because to the best of our knowledge,apart from one single-center study from Poland, there is no analysis evaluating different DAA therapies all together in a GT1b-infected population with identifying negative predictors of SVR[18]. Therefore,we can refer to the prognostic factors of virologic response in the GT1b-infected patients established for a specific DAA regimen, but the findings are inconsistent. Male sex was the only negative prognostic factor for SVR in Polish patients with GT1b infection treated with different DAA options, as well as in Romanian patients receiving OBV/PTV/r + DSV ± RBV[17,18]. However, a study of Chinese GT1binfected patients treated with another GT-specific regimen GZR/EBR showed that sex did not affect virological response[46]. A multivariate analysis involving a cohort of GT1-infected United States veterans treated with LDV/SOF documented cirrhosis and thrombocytopenia as negative predictors of virologic response, but GT1a-infected patients were the overwhelming majority[32]. In contrast to our study, an integrated analysis of the use of LDV/SOF in phase 2 and 3 trials showed prior treatment failure as a negative factor but once again, the analysis involved patients infected with both subtypes of GT1 with an advantage of 1a[47]. Both GT1 subtypes, also with predominance of 1a, were analyzed by the RWE study, Backuset al[16] established that the negative predictor of virological response in both LDV/SOF ± RBV and OBV/PTV/r + DSV ± RBV regimens is BMI > 30 kg/m2. The same treatment regimens were evaluated in a study of Spanish GT1-infected patients but this time with a predominance of subtype 1b (83.7%) and the only negative predictor for SVR was low albumin level, while the degree of fibrosis did not affect the virologic response, as did in our analysis[15]. An interesting finding in our analysis is a documented HIV co-infection as an independent negative SVR predictor. In the era of IFN,this group of patients was considered difficult to treat, however, data from the DAA era indicate no negative impact of HIV co-infection on the SVR rate[34,48]. We do not have an answer to explain our results because there is no study directly assessing GT1b-infected patients with HCV monoinfection and HIV co-infection treated with DAA. It should be noted, however, that we did not collect data on adherence to treatment in our analysis which is a factor that may be important in the HIV-coinfected population.

This is one of the limitations of our study that we are aware of. Other limitations of the analysis arise from its retrospective nature with possible entry errors, bias and underreporting AEs. The strongest point of our study was the analysis of a large real-world population from an entire country which is homogeneous in terms of HCV GT and subtype, but very diverse in terms of other important factors,including liver fibrosis, history of previous therapy, comorbidities, coinfections and therapeutic regimens used. This means that the obtained results can be generalized to the entire population infected with GT1b HCV.

Table 7 Safety of antiviral therapy in genotype 1b-infected patients according to treatment regimens

CONCLUSION

In a large real-world population of patients infected with GT1b, we have documented a very high effectiveness and good safety profile of DAA therapy, regardless of the therapeutic regimen used. Positive predictors of SVR were female sex, absence of decompensated cirrhosis at baseline and a higher platelet count, while HIV coinfection reduced the chance of cure.

Figure 1 Treatment effectiveness (sustained virologic response rates) according to treatment regimens per protocol analysis. ASV:Asunaprevir; DCV: Daclatasvir; DSV: Dasabuvir; EBR: Elbasvir; GLE: Glecaprevir; GZR: Grazoprevir; LDV: Ledipasvir; OBV: Ombitasvir; PIB: Pibrentasvir; PP: Per protocol; PTV/r: Paritaprevir; RBV: Ribavirin; SOF: Sofosbuvir; SVR: Sustained virologic response; VEL: Velpatasvir; VOX: Voxilaprevir.

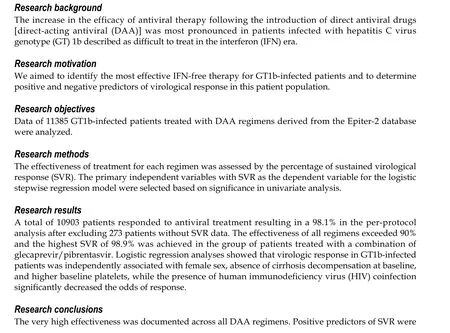

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research perspectives

The obtained data constitute the basis for selecting the most effective therapy in the case of GT1binfected patients with no positive predictors and the presence of negative predictors of DAA therapy effectiveness.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Zarębska-Michaluk D and Flisiak R conceived the study design, acquired the data; Zarębska-Michaluk D and Brzdęk M analyzed and interpreted the data; Zarębska-Michaluk D drafted the manuscript; Brzdęk M prepared tables and figures; Jaroszewicz J acquired the data, performed statistical analysis; Flisiak R prepared figures; Tudrujek-Zdunek M, Lorenc B, Klapaczyński J, Mazur W, Kazek A, Sitko M, Berak H, Janocha-Litwin J,Dybowska D, Supronowicz Ł, Krygier R, Citko J, Piekarska A acquired the data and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Institutional review board statement:According to local law (Pharmaceutical Law of 6th September 2001, art. 37al),non-interventional studies do not require ethics committee approval.

Informed consent statement:All study participants provided informed consent for treatment and processing of personal data.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Data sharing statement:Dataset available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author at dorota1010@tlen.pl.

STROBE statement:The authors have read the STROBE Statement-checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement-checklist of items.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Poland

ORCID number:Dorota Zarębska-Michaluk 0000-0003-0938-1084; Michał Brzdęk 0000-0002-1180-9230; Jerzy Jaroszewicz 0000-0003-0139-4753; Magdalena Tudrujek-Zdunek 0000-0002-5640-5432; Beata Lorenc 0000-0002-6319-9278; Jakub Klapaczyński 0000-0003-0209-1930; Włodzimierz Mazur 0000-0001-9023-2670; Adam Kazek 0000-0002-5657-4025; Marek Sitko 000-0003-3078-8604; Hanna Berak 0000-0002-0844-9158; Justyna Janocha-Litwin 0000-0002-6072-4559; Dorota Dybowska 0000-0002-1961-8519; Łukasz Supronowicz 0000-0001-7747-6187; Rafał Krygier 0000-0003-3821-6854; Jolanta Citko 0000-0003-0323-9466; Anna Piekarska 0000-0002-7188-4881; Robert Flisiak 0000-0003-3394-1635.

S-Editor:Wang JJ

L-Editor:Filipodia

P-Editor:Wang JJ

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- COVID-19 drug-induced liver injury: A recent update of the literature

- Gastrointestinal microbiota: A predictor of COVID-19 severity?

- The mononuclear phagocyte system in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Deep learning based radiomics for gastrointestinal cancer diagnosis and treatment: A minireview

- Endoscopic mucosal resection-precutting vs conventional endoscopic mucosal resection for sessile colorectal polyps sized 10-20 mm

- Meta-analysis on the epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease in China