Written on the Walls

2022-06-15

Throughout Chengdu, the rainy capital of southwest China’s Sichuan province, the word “DENS” reigns supreme in the world of underground graffiti.

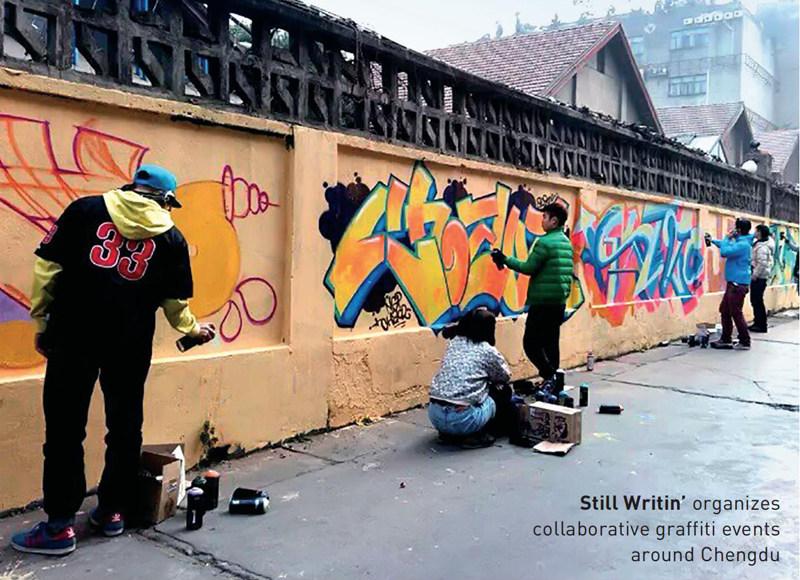

It’s a signature (known as a “tag” in the street art world) found across the city: under bridges, in back alleyways, on top of billboards. Yet the man behind the moniker is no masked marauder: His real name is Peng Dengke, and anyone who wants to can find him behind the counter at Still Writin’, the graffiti shop he co-owns, where artists can buy the spray cans that fuel much of the graffiti culture of the region. “Actually, the space is government-related,” he says, as he shows TWOC round the shop, smiling. “They’re really supportive of what we do.”

This is an understatement. In many ways, Still Writin’ only exists because of the tacit support of the local government, which has partnered with a private company to transform the neighborhood around the shop into a “culture district” called Red Star. As one of the businesses within Red Star, Still Writin’ is expected to frequently host events and draw visitors. “They want to mainly use it to attract people to the area and make the city cooler,” Dens says.

This isn’t just a Chengdu phenomenon. In order to beautify their communities, local administrators from Xi’an in the northwest to Hunan in the central-south have partnered with street artists to transform graffiti from a once-niche, underground hobby practiced by a select few into a full-blown business. But by partnering with the establishment, elements that attracted some to the subculture are slowly disappearing.

In many countries, graffiti is akin to vandalism, a serious crime worthy of prison time and high fines. In 2010, a Swiss national named Oliver Fricker was caught doing graffiti at a train station in Singapore, and was subjected to physical caning and jail time. In the US, to prevent youths from even engaging in graffiti, most major cities store their spray cans in cages, and you have to be at least 18 years old to purchase them. But in China, Dens often sells to high school students.

China’s laws regarding public spray paint have historically been lax. Despite a long history of writing political slogans on walls, the first real instance of contemporary graffiti in China can be traced back to one man: Zhang Dali, who started spray-painting rough murals of his own bald head on buildings slated for demolition in the mid-1990s. At that time, his work was seen as a veiled attack on the rampant demolition and urbanization of Beijing’s many old-style streets.

But whereas graffiti has been a source of protest against the establishment (political or social) in the West, it developed other practical uses alongside China’s rapid urbanization. Messages on walls advertising fake IDs and rentals, or marking walls for demolition with the character 拆 (“demolish”), are common enough to fade into the background of China’s urban landscape. As such, there have been no serious rules prohibiting it, and according to Dens, this “gray area” is what initially allowed graffiti to flourish largely unregulated and ignored for much for the past two decades as China’s cities continued to grow in scale.

However, the recent popularity of a generalized graffiti aesthetic, with its bright, colorful bubble-letters and pleasing curves, as well as the mass appeal of “street culture,” has become a trend that is impossible to ignore.

Paul “Dezio” Coello, a French graffiti artist who has lived and worked in Shanghai for the past 16 years, attributes much of the popularity of modern graffiti culture in China to the “golden era” between 2006 and 2010, where blank walls were plenty and police nowhere to be seen. “When I first came to Shanghai in 2006, there were only a few people doing graffiti,” Dezio, who is considered by some peers to have been one of the founders of Chinese contemporary street art, tells TWOC. “Maybe a maximum of 10 to 14 people in all of China.”

Both Dens and Dezio place particular emphasis on the Beijing Olympics of 2008 and the Shanghai World Expo of 2010 as the cultural catalysts that allowed graffiti to take root in China.

“At that time, China was trying to be more open and attract people,” Dezio says. At the Shanghai World Expo, some countries brought over young artists to create murals for their pavilions. This exposed many people to graffiti for the first time as a legitimate art form. “Those two events really changed everything,” says Dezio, who estimates that China went from having a dozen “graffiti writers” (artists who only create tags) to hundreds in two years after the Olympics.

Government got in on the act too. Ahead of the 2008 Olympics, the Beijing government sanctioned a 730-meter-long “spray paint zone” for patriotic murals. Even before that, the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts in Chongqing commissioned a massive “Graffiti Street” located at Huangjueping in 2006. By the time it was completed 150 days later, a total of 12.5 tons of paint had been used by more than 800 artists, earning it a nod as the “world’s longest graffiti street” from the Guinness Book of World Records.

When he painted on the streets, Dezio recalls mostly positive feedback from pedestrians. “In France, people would shout at me and call me a vandal. Here, children and their grandparents would watch me paint, and sometimes they would even join in,” he claims. “Following those two events, it was a very open time, with lots of opportunities.”

Not everyone agrees. Zhang Dali has ceased to do graffiti altogether since 2006, citing concerns that it was becoming just a “fashion” in China and losing all meaning as a form of protest, according to a Vice News interview in 2014.

As more and more young people in cities across China embrace the aesthetic, so do local government offices, real estate developers, and corporate sponsors, all of whom clamor to work with graffiti artists in order to beautify their streets, enrich their brand’s image, or draw visitors to a certain area.

These policies have continued to advance across China, aided and abetted by government initiatives for urban and rural rejuvenation. “A few years ago, there was a ‘beautiful countryside policy’ that allowed many villages to paint their walls,” says Chen Yang, a graffiti artist from Jiangxi province better known as Sheep Chen. Many grassroots-level governments organized painting activities, provided equipment and painting materials, and let the artists express themselves. Chen has painted in a county in the central Hunan province and a district of Xi’an, capital of Shaanxi province in the northwest, among other places.

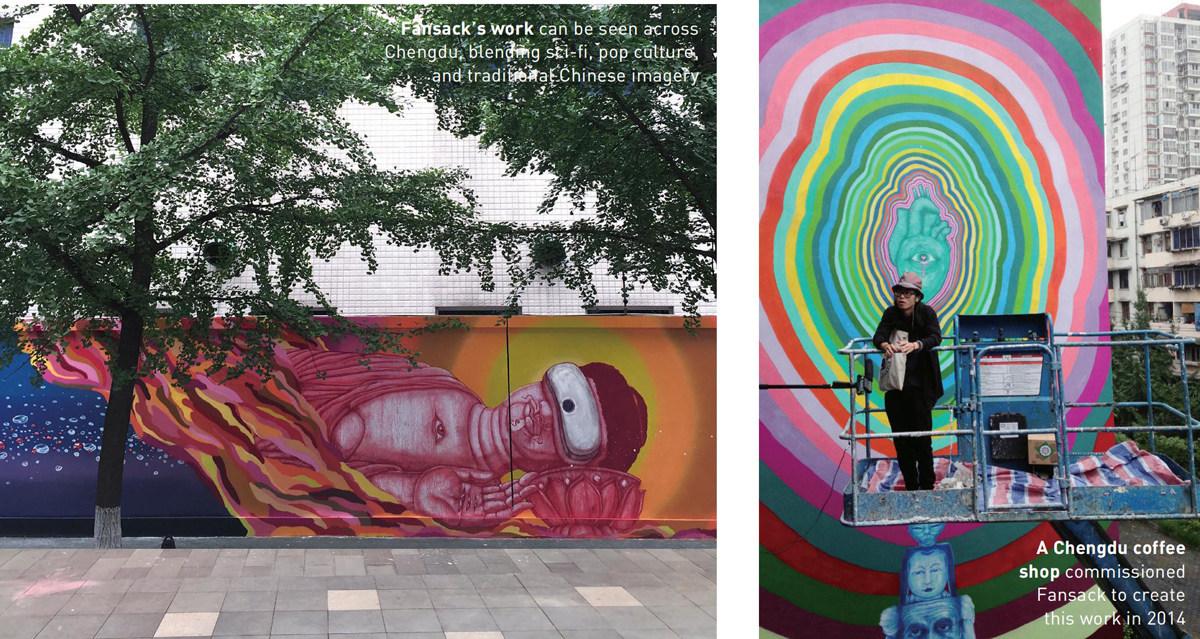

Some have benefited from this drive, like 33-year-old Pang Fan, better known by his street name Fansack. A graduate of art at the Sorbonne in France, Fansack also got his start in Chengdu, doodling on walls back when he was still in high school. Since he returned to China in 2019 armed with his degrees and a little international buzz through the fine-art circuits of Paris, Hong Kong, and Taipei, Fansack’s commercial and government collaborations have been vast and, for the most part, profitable. He’s worked with everyone from Adidas to KFC, and rarely does anything for free.

His is far from the anti-establishment vibe of other street artists like Banksy (whom Fansack has sometimes referenced in his work). “Urban art must have a positive effect on urban life,” he tells TWOC, his studio buzzing with activity as he prepares for an exhibition at the Shanghai Museum of Contemporary Art later this year. “To create in such a public space, and be appreciated by as many people as possible, this is a happy thing.”

Artists can still go it alone underground, as long as they follow certain unspoken rules. “Nothing on government property, and nothing political, religious, or pornographic,” lists Dezio, calling them a set of uncodified “Cardinal Rules” that all street artists are aware of. “And you can’t be too open about it. That’s it.”

Break these rules, and the repercussions can be severe. “There was a guy in Chengdu once,” says Dens. “He painted some political content across from the American Consulate when it was closing in 2020. The police got him, and he’s still in jail now.”

But these instances are few and far between. Whether by design or by necessity, most graffiti artists don’t rock the boat. As a result, punishments are rare, and most altercations with the police end up in peaceful negotiations. “You usually just have to clean the wall, or something like that,” says Dens, who even now still goes out painting large swaths of surfaces (known as bombing) in Chengdu with impunity. “Maybe sign a piece of paper saying you will never do graffiti on that street again.”

Chengdu has a reputation for being a graffiti haven due to its slow development and the relaxed nature of the city, but Dens’s experience is backed up by Dezio. In the latter’s 16 years of painting in China, he’s only ever seen a big pushback against graffiti once, following a five-day painting event in Changsha called the “Meeting of Styles” in 2011. Graffiti writers gathered from all over China, and went out openly bombing all night. Nothing happened until the third day, when police arrived and arrested any artists they saw. They were “breaking the cardinal rules,” Dezio explains.

But the punishment was light. Although around 30 people were rounded up and fined 6,000 yuan in total, “they all got together and split the bill,” says Dens. “So it was only a couple hundred each. And they were free to go.”

Can street art that is backed by the government, whether through direct action or inaction, still be considered “graffiti?” In response to this question, Fansack points out that graffiti culture in Western countries is also becoming less subversive than it used to be, and artists there also collaborate on art projects with governments. “Sure, there are some street artists who think we should stay underground...and I respect that. But with age, we should also grow, adapt, and mature,” he says. Being largely removed from politics also seems to allow artists like Fansack and Sheep Chen to explore vastly different themes than their Western counterparts, such as China’s own poetry, folklore, and ancient cultural symbols.

But this migration to the mainstream comes with consequences. Although Dens is excited about young people’s interest in graffiti, he is skeptical about where it is headed. “Many kids just do it in order to take pictures and post on their personal blog, then never do it again. For me, I go out at night and paint with friends because it’s a way of life, and I like the community.”

But he fears the community is disappearing, along with the blank walls that sustain it: Just as the rise of graffiti culture coincided with the rise of China’s new real estate projects and their copious amounts of wall space, spaces for free spray-painting are shrinking.

“There are fewer and fewer places to really experiment, and more and more cities don’t allow people to paint freely anymore.” Dezio says. “It used to be that virtually every university in China had walls for their students to paint on, but they’re completely disappearing, along with the culture.” Perhaps in the future, a blank wall that was once a limitless canvas for experimentation will become a perfect spot for an advertisement or brand collaboration with the “right” urban artist.