Trends in the management of anorectal melanoma: A multi-institutional retrospective study and review of the world literature

2021-02-04JoshBleicherJessicaCohanLyenHuangWilliamPecheBartleyPickronCourtneyScaifeTawnyaBowlesJohnHyngstromElliotAsare

Josh Bleicher, Jessica N Cohan, Lyen C Huang, William Peche, T Bartley Pickron, Courtney L Scaife, Tawnya L Bowles, John R Hyngstrom, Elliot A Asare

Abstract

Key Words: Melanoma; Anorectal melanoma; Literature review; Melanoma surgery; Surgical oncology; Colorectal surgery

INTRODUCTION

Anorectal melanoma (ARM) is a rare malignancy with a poor prognosis. The estimated annual incidence in the United States is less than 5 cases per 10 million[1]. Overall 5-year survival is between 10% and 20%[2]. This low survival is due to the late diagnosis of most tumors and aggressive biology of ARM[3]. Most tumors are first recognized from symptoms such as bleeding, obstruction, pain, or changes in bowel habits[4-6]. When these tumors are recognized, they are often misdiagnosed as hemorrhoids or other benign anorectal pathology[7].

National Clinical Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines on melanoma do not currently include recommendations for treatment of ARM[8]. Without guidelines, and due to the rare nature of the tumor, treatment is highly variable. Controversy exists over optimal primary surgical therapy. Some advocate abdominoperineal resection (APR) for initial treatment, while others report similar oncologic outcomes with wide excision (WE) alone[9,10]. As outcomes are universally poor, many providers recommend the less invasive and lower morbidity WE as primary treatment[11]. Optimal primary nodal management strategy is also unknown. Non-surgical therapy is even more varied. Radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapies (including interferon, checkpoint-inhibitors, anti-BRAF therapy, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors) have all been used alone or in various combinations[12-17]. No clear treatment strategy has emerged as the gold standard for treatment of this rare but aggressive disease.

Given the lack of guidelines and variability in reported practice patterns, we analyzed outcomes from a multi-institutional cohort of patients with ARM. We also provide an updated review of the literature to compare outcomes from across the decades and around the world. This review allows for analysis of overall trends to help guide treatment decisions for patients with ARM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

We retrospectively reviewed patients diagnosed with ARM between January 1, 2000 and January 1, 2019. This allowed for at least 12 mo of follow-up for all patients. Patients were identified using international classification of diseases-9/10 codes in prospectively maintained institutional tumor registries at 7 centers near Salt Lake City, Utah. These centers included the University of Utah Huntsman Cancer Institute and 6 hospitals affiliated with Intermountain Health Care. All names were linked across institutions to ensure only unique patients were included in the study.

Data Collection

We abstracted data from the electronic medical record and institutional tumor registries. Manual chart review was performed for all records to verify data and obtain additional information. Data abstracted includes patient demographics, primary tumor characteristics, treatment details, and cancer-related outcomes. Both adjuvant therapy and therapy at time of relapse were recorded. Specific chemotherapy and immunotherapy agents were noted. Vital status was available for all but one patient.

Extent of disease was categorized into local, regional, or distant depending on whether disease was confined to the anorectum, involved regional lymph nodes, or other organs[3]. Extent of disease classification was based on clinical documentation. The extent of primary surgical therapy was also determined by clinical documentation. The Institutional Review Boards of the University of Utah and Intermountain Health Care approved this study.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata Version 15.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, United States). We analyzed patient demographics, initial tumor characteristics, and treatment details using descriptive statistics. We calculated median time to recurrence, melanoma-specific survival (MSS), and overall survival (OS) for the cohort and determined MSS and OS at 2, 3, and 5-year intervals. Patients with unknown survival outcomes were excluded from OS analysis and patients with unknown cause of death were excluded from MSS analysis. We graphically evaluated these outcomes using the Kaplan-Meier method. Time-zero for all time-to-event outcomes was the date of diagnosis. Recurrence was defined as re-appearance of disease on physical exam or radiographically in patients who had been initially rendered free of disease after initial treatment. Patients were determined to be free of disease following initial therapy based on intention to treat, as described in clinical documentation.

Cox regression was used to assess for any factors associated with survival. Results were considered statistically significant if the two-sidedP< 0.05. Analysis of outcomes associated with different surgical and non-surgical treatment options was performed in a similar fashion. Multivariable analysis was not performed because of the small sample size of this cohort.

Review of the literature

We performed a literature review using the PubMed database. The 2009 PRISMA checklist was used to ensure transparent reporting of search and review methodology[18]. The search term used was “ARM.” Search results did not differ significantly when “anal melanoma” or “rectal melanoma” were considered separately. All English language articles were included. Articles were excluded if they did not describe outcomes of a unique cohort of at least 10 patients. When multiple articles described overlapping patient cohorts, the most recent and inclusive article was used. Studies describing patient outcomes from national databases in the United States were excluded, as these patients are often represented in other institutional studies. National database studies from other countries were included when other cohorts from these countries did not exist. All titles and abstracts were reviewed for inclusion.

Once this review was complete, all full-length articles were reviewed. Outcomes of interest were surgical management of patients, median OS, and 5-year OS. No summary of outcomes was performed because of the significant heterogeneity among the various studies.

RESULTS

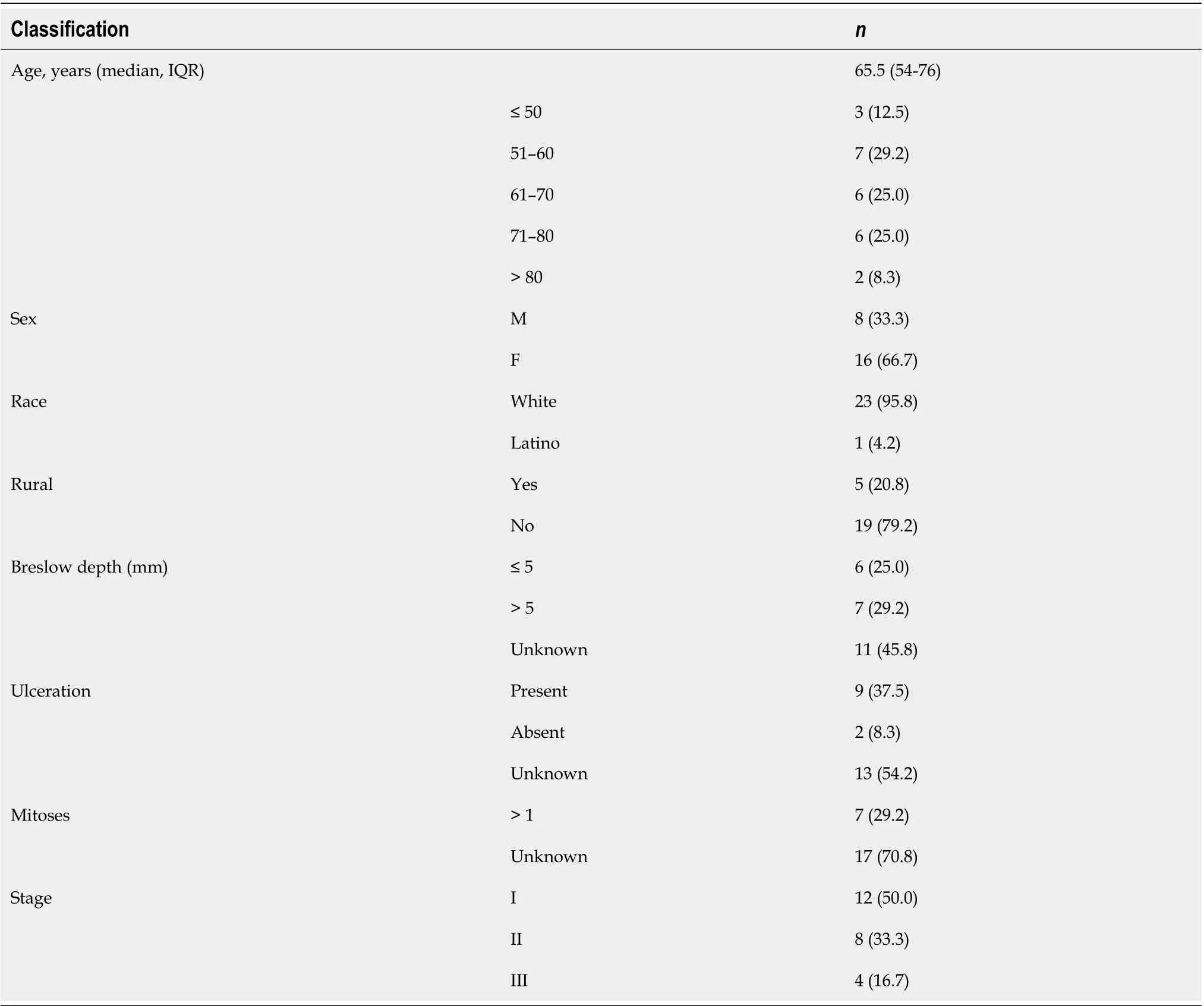

Twenty-four patients met inclusion criteria. Two-thirds of patients were female, with median age of 65.5 [interquartile range (IQR) 54-76] (Table 1). Patients were from five different states (UT, ID, WY, NV, CO) and approximately 20% of patients were from rural communities. Of 13 patients with information on Breslow depth, 7 (53.8%) were > 5 mm. There were 9 (37.5%) patients whose melanoma exhibited ulceration (Table 1). Half of the patients had advanced disease at diagnosis; 8 with nodal disease and 4 with distant metastases.

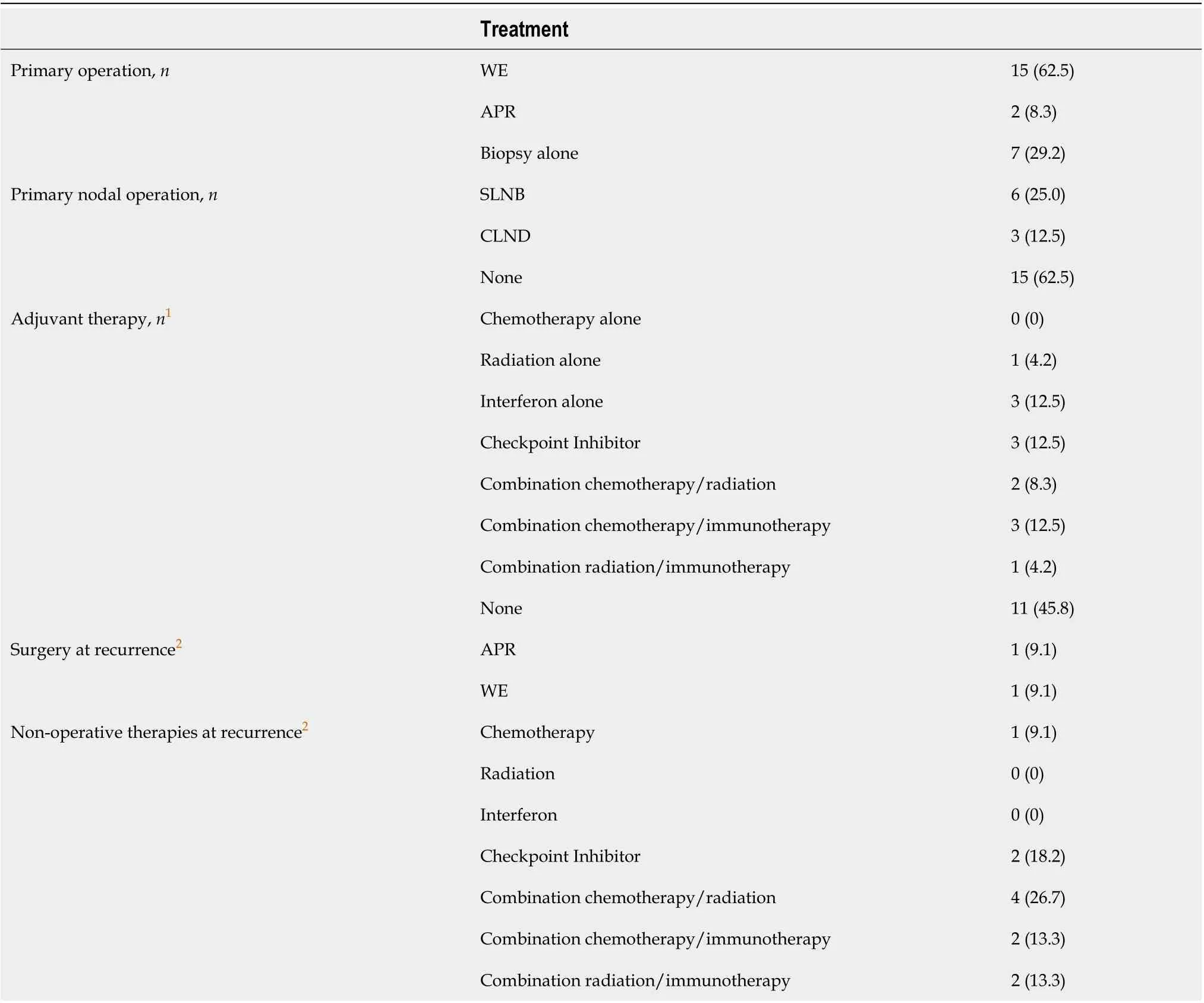

Fifteen patients (62.5%) underwent WE at diagnosis and 2 patients (8.3%) underwent APR (Table 2). Seven patients (29.2%) received biopsy alone, including 2/4 patients with distant disease at diagnosis. The primary operation took place at a median of 27 d after diagnosis (IQR 0-47). Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) was performed in 6 (25%) patients. Of those with local or nodal disease, nearly half of patients received surgery alone as primary management. The remainder of patients received systemic therapy of some form following surgical resection. There was wide variation in adjuvant treatment. Some patients received chemotherapy, radiation, interferon, or checkpoint-inhibitor therapy alone; others received these in various combinations (Table 2).

Of 21 patients with complete follow-up data, only 2 (9.5%) remained free of disease after resection. One of these patients died of metastatic colon adenocarcinoma 13.9 mo after ARM diagnosis. The other patient was alive at last follow-up with no evidence of disease 21.4 mo from diagnosis. Excluding the 4 patients with distant disease at diagnosis, 3 (20.0%) of the remaining 15 patients were never free of disease and the remaining 12 (80.0%) recurred after initial treatment. One patient who was never free of disease underwent APR as salvage therapy. Median time to recurrence was 10.4 mo (IQR 7.5-17.2). At the time of recurrence, 4 patients (33.3%) opted not to pursue further therapy given their age, comorbidities, and/or overall prognosis. Of those who received further treatment (n= 8), only 1 patient had surgery (repeat WE and bilateral inguinal lymph node dissection). Use of systemic therapy was highly variable. Individual patient treatments and outcomes are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

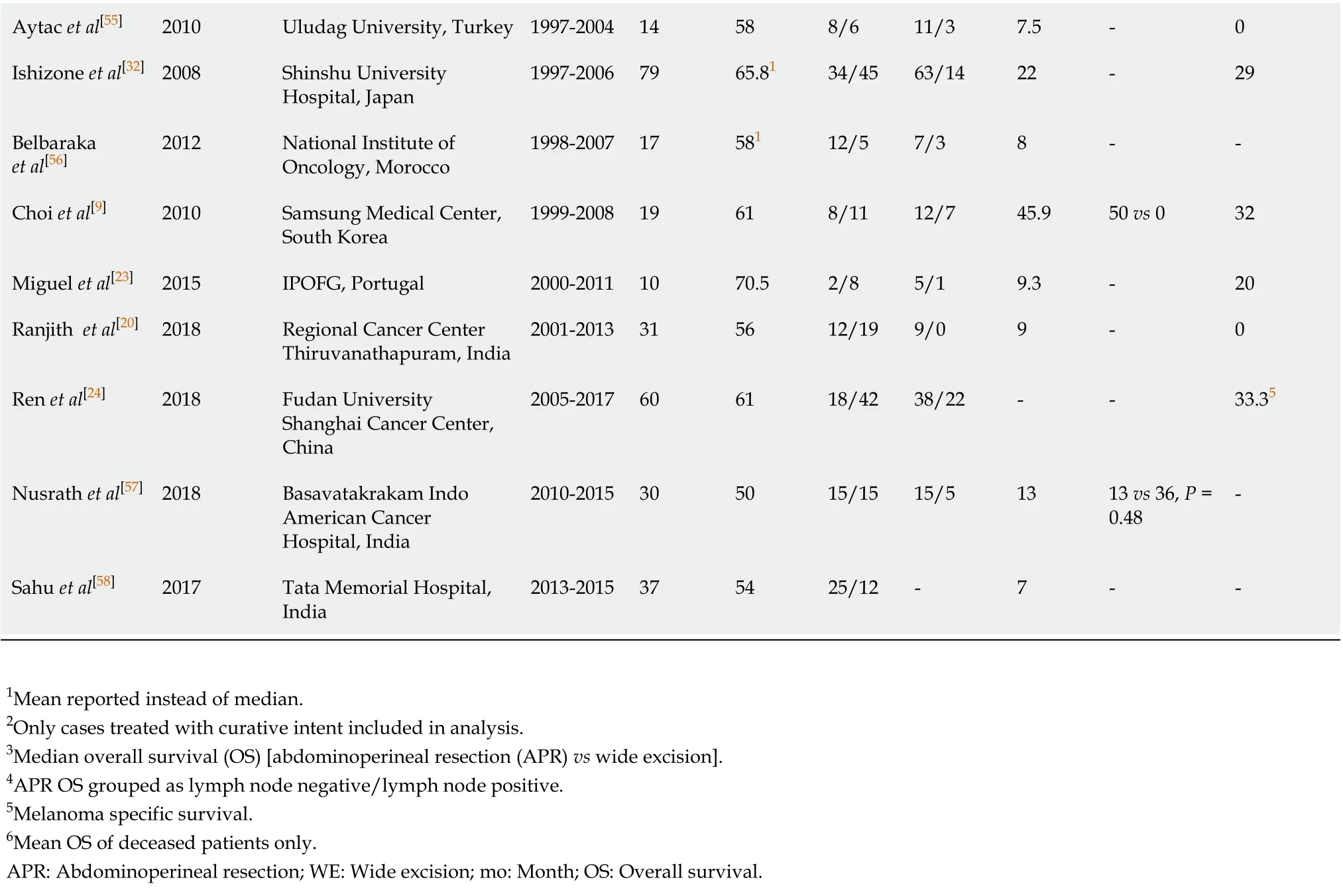

Survival status was known for all but 1 patient. Of these 23 patients, 1 (4.3%) was alive at last follow-up (21.4 mo from diagnosis). Fourteen (60.9%) died from ARM. The cause of death was unknown for 7 (30.4%) patients. Median OS was 18.8 mo (IQR 13.5-33.9) with 0 survivors at 5 years (Figure 1A). Two-year OS was 21.0% (95%CI: 6.8%-40.3%) and 3-year OS was 10.4% (95%CI: 1.8%-27.9%). Median MSS was 19.5 mo (IQR 14.8-35.1) (Figure 1B). Two-year MSS was 29.1% (95%CI: 9.1%-53.0%) and 3-year MSS was 14.6% (95%CI: 2.4%-37.0%). Excluding patients with distant disease at diagnosis, median OS was 19.9 mo (IQR 16.0-35.1) with 2-year OS of 25.5% (95%CI: 8.2%-47.3%) and 3-year OS of 12.7% (95%CI: 2.2%-33.0%). Median MSS was 19.9 mo (IQR 16.4-39.8) with 2-year MSS of 36.4% (95%CI: 11.2%-62.7%) and 3-year MSS of 18.2% (95%CI: 2.9%-44.2%).

Age, sex, rural location, mitoses, ulceration, and Breslow depth were not prognostic of OS. Patients with distant disease at diagnosis had higher risk of mortality than patients with local disease [hazard ratio (HR) = 14.6 (95%CI: 2.5-86.7)] or nodal disease [HR = 14.4 (95%CI: 2.2-92.1)]. No differences in OS were noted for patients who underwent APRvsWE as their primary operation [HR = 1.4 (95%CI: 0.3-6.8)]. There was no significant difference in OS between patients who underwent nodal surgery [SLNB or completion lymph node dissection (CLND)] and those who did not [HR = 0.4 (95%CI: 0.1-1.1)]. Exclusion of patients with distant disease at diagnosis did not alter these results. No individual adjuvant therapy (immunotherapy, radiation, or chemotherapy) demonstrated a benefit over another therapy for patients with local or nodal disease treated with surgery as initial treatment.

Review of the literature

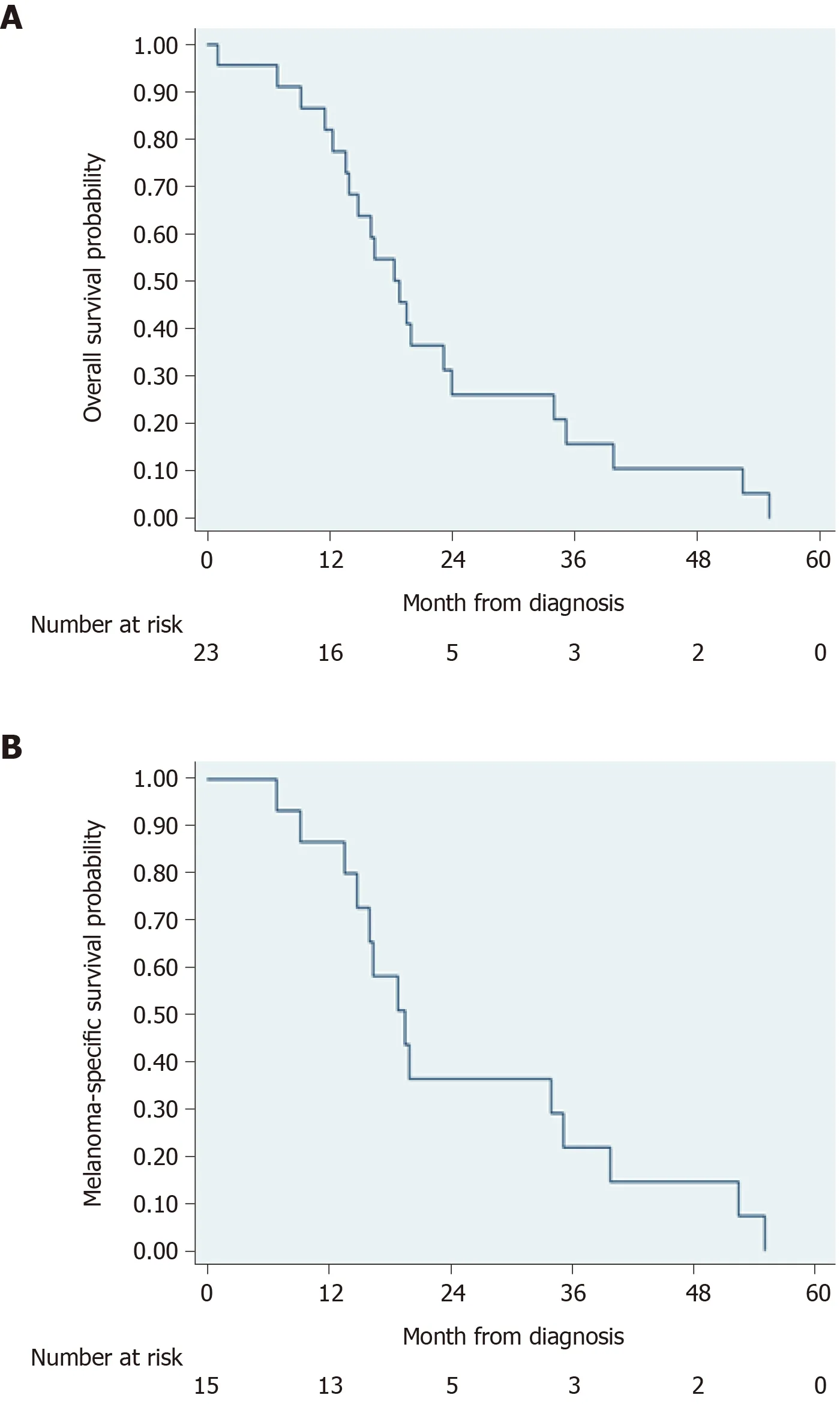

This search revealed 360 unique articles, of which 33 were included for review (Figure 2). Cohorts differed across studies, with some including all patients diagnosed with ARM and others limited to only patients with local or nodal disease or patientstreated with curative intent. Twenty-five studies reported median OS (Table 3). Median OS ranged from 7-49.5 mo and 21 (84%) studies had median OS < 25 mo. There was wide variation in the type of surgical management across studies. At some centers, all patients received WE while other centers treated all patients with APR[10,19,20].

Table 1 Demographics and primary tumor characteristics for cohort with anorectal melanoma (n = 24)

Eight studies achieved a 5-year OS rate of 20%. Three of these studies included patients diagnosed before 1980, with 1 study including patients from the 1930s[10,21,22]. The other five study cohorts spanned into the 2000s. Surgical management of patients was mixed in this subset of studies. In a study of 54 patients with ARM treated at MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) from 1989-2008, all patients with local disease underwent WE followed by radiation therapy and a 5-year OS of 30% was reported[10]. In another study from South Korea, authors described 12 patients who underwent APR and 7 who underwent WE with significantly improved OS with APR compared to WE[9]. In the remainder of studies, 3 studies reported no significant differences between APR and WE and 3 did not report results of this comparison[7,21-24]. No other dominant themes in surgical or non-surgical treatment were noted across these studies with superior survival outcomes.

Across all studies, the number of APRs was similar to WEs. In total, 427 patients had APR and 436 underwent WE. Studies from the same institution at different time points showed a trend towards performing fewer APRs with time. In two studies from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) looking at cohorts from 1950-1977 and 1984-2003, 73.3% of patients underwent APR in the older cohort compared to 41.3% in the more recent cohort[25,26]. At MDACC, Rosset al[27]reported APR in 53.8% of patients from 1952-1988 while Kellyet al[10]reported exclusive treatment with WEbetween 1989-2008, as noted previously[10,27].

Table 2 Treatment details for cohort with anorectal melanoma (n = 24)

Geographic variation in surgical management exists. In United States cohorts, 45.7% (132/289) of surgical patients underwent APR, down to 24.3% over the past 40 years (35/144). European cohorts were similar with 45.1% of patients undergoing APR (123/273). Asian (China, South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan) and Indian cohorts had higher rates of APR with 69.9% (200/286) and 79.7% (51/64) of patients receiving APR as primary surgical therapy respectively. Daset al[19]and Ranjithet al[20]report cohorts from India with 100% of patients undergoing APR[19,20].

DISCUSSION

Dr. George Pack wrote in 1967, “cures are possible although they do not occur with encouraging frequency[19]”. This study confirms the dismal prognosis associated with ARM. Only 1 patient from our study cohort was alive at last follow up, and there were no 5-year survivors. Only 6/33 studies reviewed reported a 5-year OS > 20%, and some of these studies included only patients with local disease. Most studies reported median OS of less than 2 years, and many less than 1 year. There is no compelling evidence from this review that a significant improvement in survival has been made for patients with ARM since 1967.

This study also demonstrates the wide variation in surgical treatment for ARM, bothwithin and between medical centers. Geographic variation also exists, with United States and European centers more likely to perform WE and Asian and Indian centers more likely to perform APR. This finding was true in our cohort, with few patients undergoing APR. While low sample size limits analysis, there was no difference in survival outcomes between patients undergoing WEvsAPR. Multiple other groups have demonstrated similar or better outcomes with WE compared to APR[10,28]. This same conclusion has been reached using larger cohorts from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results and National Cancer Database (NCDB)[1,11,12]. A prior systematic review concluded that while APR may reduce local recurrence, there is no improvement in OS or recurrence-free survival compared to WE[29].

Table 3 Studies included in literature review and select outcomes

Aytac et al[55]2010 Uludag University, Turkey 1997-2004 14 58 8/6 11/3 7.5-0 Ishizone et al[32]2008 Shinshu University Hospital, Japan 1997-2006 79 65.81 34/45 63/14 22-29 Belbaraka et al[56]2012 National Institute of Oncology, Morocco 1998-2007 17 581 12/5 7/3 8--Choi et al[9]2010 Samsung Medical Center, South Korea 1999-2008 19 61 8/11 12/7 45.9 50 vs 0 32 Miguel et al[23]2015 IPOFG, Portugal 2000-2011 10 70.5 2/8 5/1 9.3-20 Ranjith et al[20]2018 Regional Cancer Center Thiruvanathapuram, India 2001-2013 31 56 12/19 9/0 9-0 Ren et al[24]2018 Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center, China 2005-2017 60 61 18/42 38/22--33.35 Nusrath et al[57]2018 Basavatakrakam Indo American Cancer Hospital, India 2010-2015 30 50 15/15 15/5 13 13 vs 36, P = 0.48-Sahu et al[58]2017 Tata Memorial Hospital, India 2013-2015 37 54 25/12-7--1Mean reported instead of median.2Only cases treated with curative intent included in analysis.3Median overall survival (OS) [abdominoperineal resection (APR) vs wide excision].4APR OS grouped as lymph node negative/lymph node positive.5Melanoma specific survival.6Mean OS of deceased patients only.APR: Abdominoperineal resection; WE: Wide excision; mo: Month; OS: Overall survival.

WE allows for avoidance of a colostomy and significantly reduced morbidity compared to APR. A study of 49 patients undergoing WE demonstrated the safety of this procedure; 3 patients had minor infections requiring antibiotics and 1 patient required a second operation for postoperative bleeding. No other complications from surgery occurred[10]. While most studies of APR for ARM have not reported complication rates, APR for other indications is known to be associated with significant morbidities. Perineal wound complications occur in up to 40% of patients and 50% of patients develop genitourinary and/or sexual dysfunction postoperatively[30]. No studies currently exist in ARM that compare quality of life between WE and APR[31]. Some centers continue to routinely perform APR for ARM patients; however, we did not find evidence in this review to support this practice[9,19,20,32].

Nodal management also differs widely. In our cohort, there were no significant differences in survival outcomes between patients who underwent initial nodal surgery (SLNB or CLND) and those who did not. Nearly 2/3 of patients did not receive any nodal staging or treatment. Older studies hypothesized that the benefit of APR was largely secondary to the mesorectal lymphadenectomy performed with this procedure[25]. However, Yehet al[26]found that the presence of lymph node metastases had no prognostic significance on survival in 19 patients who underwent APR at MSKCC[26]. Many patients in this cohort received local surgery alone and did not receive additional therapy until the time of recurrence. Some of these patients likely had unidentified nodal disease at the time of initial surgery. If patients had undergone SLNB and were found to have positive nodal disease, adjuvant systemic therapy could have been initiated sooner. The impact this may have had on survival is unknown. This review did not find studies with large enough patient numbers to make conclusions regarding the benefits of nodal surgery.

Figure 1 Overall mortality and melanoma-specific mortality in cohort of patients with anorectal melanoma. A: Overall mortality; B: Melanomaspecific mortality.

Use of immune checkpoint inhibitors and targeted therapies is also controversial and evidence is lacking to help with decision making. While checkpoint inhibitors, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and BRAF/MEK inhibitors have significantly improved outcomes for cutaneous melanoma over the past decade, their role in treatment of ARM remains unknown[33-36]. Results of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy for ARM are limited and show mixed outcomes. Tokuharaet al[13]reported a case of a 67-yearold male with ARM who had no oncologic progression of disease for 17 mo after initiation of anti- programmed death 1 (PD-1) therapy[13]. Conversely, Faureet al[37]reported a case of a 77 year-old male with ARM who progressed rapidly on anti-PD-1 therapy[37]. Higher level evidence of the effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in treating ARM is lacking[13,38]. While immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy has helped individual patients with ARM, the efficacy of this treatment in most ARMs has been questioned as most ARMs do not exhibit 1-PD-ligand expression and few have tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes[25]. Evidence for other targeted therapies is similarly poor[2]. The genomic profiles of ARMs differ from cutaneous melanomas, with very low BRAF expression and few NRAS and KIT mutations[39]. ARM likely has different drivers of metastases with fewer targetable mutations. Although a rare disease, clinical trials are necessary to determine what therapies are most useful for ARM.

This study is limited by its retrospective nature and small cohort size. ARM is an extremely rare disease and only 24 cases were identified over a 20-year period. Additionally, the lack of a synoptic report for this disease has resulted in many missing pertinent variables which would have strengthened this study.

Figure 2 Flow diagram of selection of articles for literature review. ARM: Anorectal melanoma.

CONCLUSION

ARM is a highly lethal disease. Over the past 50 years, outcomes have remained largely unchanged. Without good evidence to drive treatment decisions, surgical and non-surgical management remains highly variable across the United States and the world. Even within our own cohort, management differed between patients. Review of the literature was also unable to resolve many questions on ARM. There does not appear to be survival benefit of APR over WE. With no clear advantage to APR, surgical management should aim to minimize morbidity. Many other questions on ARM management remain unanswered. Improving the quality of data on ARM is necessary. A consensus meeting of experts aimed at the identification of pertinent variables to collect would be a good first step. Additionally, clinical trials to assess the role of sentinel lymph node biopsy, targeted therapies, radiation therapy, and treatment sequencing are needed.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research methods

We performed a retrospective study of patients who were diagnosed with ARM at 7 hospitals in the Salt Lake City, UT region. We analyzed factors prognostic for recurrence and survival. We also performed a review of the literature to assess regional and temporal trends in ARM management.

Research results

We identified 24 patients diagnosed with ARM between 2000-01 and 2019-05. 12 (50.0%) had local, 8 (33.3%) regional, and 4 (16.7%) distant disease at diagnosis. Only 2 patients who had surgical resection of their primary tumor with curative intent failed to recur. Median time to recurrence was 10.4 mo [interquartile range (IQR) 7.5–17.2] and median overall survival was 18.8 mo (IQR 13.5–33.9). No patients survived to 5 years. No survival differences were noted for patients managed with WEvsAPR. Review of the literature demonstrated regional trends in surgical management of ARM, with WE favored in the United States and Europe and APR used more frequently in Asia.

Research conclusions

ARM remains a highly lethal disease regardless of surgical treatment. Patients who undergo WE and APR have poor outcomes. No convincing evidence exists to favor APR over WE. Despite this, APR continues to be used for primary surgical management, although with decreasing frequency in the United States and Europe in recent years. We feel that surgical management should aim to minimize morbidity. WE should be favored over APR for primary surgical treatment.

Research perspectives

Further research should focus on better risk stratification and the role of targeted therapies, radiation therapy, and treatment sequencing. Improving non-surgical therapies will be critical to improving survival for patients with ARM.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Emily Z. Keung, MD, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, United States.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Screening colonoscopy: The present and the future

- Circular RNA AKT3 governs malignant behaviors of esophageal cancer cells by sponging miR-17-5p

- Serum vitamin D and vitamin-D-binding protein levels in children with chronic hepatitis B

- Comparative study on artificial intelligence systems for detecting early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma between narrow-band and white-light imaging

- Peritoneal dissemination of pancreatic cancer caused by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration: A case report and literature review