Efficacy of pancreatoscopy for pancreatic duct stones: A systematic review and meta-analysis

2020-10-09SyedSaghirHarmeetMashianaBabuMohanBanreetDhindsaAmaninderDhaliwalSaurabhChandanNeilBhogalIshfaqBhatShailenderSinghDouglasAdler

Syed M Saghir, Harmeet S Mashiana, Babu P Mohan, Banreet S Dhindsa, Amaninder Dhaliwal, Saurabh Chandan, Neil Bhogal, Ishfaq Bhat, Shailender Singh, Douglas G Adler

Abstract

Key Words: Electrohydraulic shockwave lithotripsy; Laser lithotripsy; Chronic pancreatitis; Calculi; Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy; Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; Systematic review; Meta-analysis; Outcome

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic duct (PD) stones are a common complication of chronic pancreatitis (CP), which can lead to obstruction of the PD and cause chronic abdominal pain and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency[1]. PD stones may be present in as many as 50%-90% of CP patients[1,2]. The cause of the pain is multifactorial, but is thought to be secondary to elevated pancreatic ductal pressures, elevated interstitial pancreatic pressure, ischemia, fibrosis, and inflammation-related injury to the nerves innervating the pancreas[1]. Relieving PD obstruction is an important aspect in treatment of patients with painful chronic pancreatitis.

Current management of symptomatic PD stones includes medical therapy such as pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT), extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) with or without endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), ERCP with pancreatic sphincterotomy and either balloon or basket retrieval with stent placement, peroral pancreatoscopy and/or surgery[1,2]. According to the 2018 European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) and the 2017 United European Gastroenterology (UEG) guidelines, ESWL is the first line approach for patients with painful PD stones who have failed in medical therapy and who have stones greater than 5 mm[3,4]. ERCP is recommended for stones less than 5 mm[4]. The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) 2020 guidelines recommend ERCP/interventional endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) for PD stone management[5]. If these modalities are unsuccessful, pancreatic surgery should be considered[6,7].

Per oral pancreatoscopy (POP)-guided lithotripsy is being increasingly used for the management of main pancreatic duct calculi (PDC) in the setting of CP[2,8]. Previously two operators were required to do this procedure and imaging quality was poor, but with the advent of newer technology, POP by single operator is now widely available[9]. POP uses two techniques: Electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL) and laser lithotripsy (LL). EHL technique uses a charge generator and bipolar probe to create a spark to produce a vapor plasma. The vapor plasma becomes a cavitation bubble that oscillates around the tip of the probe, which leads to stone fragmentation by absorption of rebounding shockwaves from the vapor. LL technique uses laser light at a specific wavelength to induce fragmentation[1]. Both techniques simply fragment stones into smaller pieces that still need to be removedviaballoon and basket retrieval devices.

Information about the safety profile of POP and ESWL is limited. We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis on POP to assess the two techniques with regards to stone fragmentation, safety, and efficacy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search

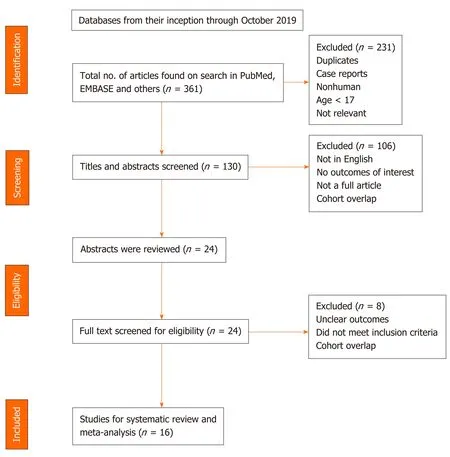

We conducted a comprehensive search of multiple electronic databases and conference proceedings including PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane, Google Scholar, and Web of Science databases (from 1999 to October 2019). We identified studies reporting on outcomes of POP-guided intracorporal lithotripsy and followed the Preferred Reporting items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines[10]. The schematic diagram of study selection as per PRISMA guidelines is illustrated in Figure 1.

Literature search keywords included a combination of “per-oral”, “pancreatoscopy”, “pancreatoscope”, “POP”, “electrohydraulic”, “EHL”, “laser”, “lithotripsy”, “LL”, “pancreas”, “calculi”, “stones”, “chronic” and “pancreatitis”. The literature retrieved was restricted to studies done on humans and published in English. Two authors (BD, HS) independently evaluated titles and abstracts obtained from the literature search and discarded any studies that were irrelevant to our topic, based on predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. We then reviewed the complete versions of the articles of interest to determine if they contained relevant context. Any article with discrepancies was reviewed by a third author (SS).

这是一个很复杂的问题,一方面云南那一段历史,的确有待我们重新认识;另一方面,讲武堂作为一所学校,的确在师资、管理和思想等方面,有独到之处。

Additional relevant articles were discovered from the bibliographic sections from the articles of interest.

Study selection

In this meta-analysis, studies that discussed the use of POP, EHL, and LL in patients with pancreatic duct stones were included. We included relevant studies for the data analysis regardless of their geographical location, inpatient/outpatient setting, or abstract/manuscript status.

The exclusion criteria included the following: (1) Alternative therapies for management of pancreatic duct stones other than POP; (2) Use of POP for indications other than for pancreatic duct stones; (3) Studies of the pediatric population (age < 17 years); and (4) Studies published in languages other than English.

In instances where there were multiple articles from the same cohort or overlapping cohorts, we used the ones that were the most relevant, comprehensive and/or recent.

Figure 1 Study selection process in accordance with preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis statement.

Data extraction

Information regarding study-related outcomes from the individual studies was extracted onto a standardized form by three authors (BD, HM, SMS).

Risk of bias

The collected data was evaluated akin to single group cohort studies and thus, we used the Newcastle-Ottawa scale to assess the quality of these studies[11]. Details of the scale is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Statistical analysis

The pooled estimates were calculated with meta-analysis techniques as per DerSimonian and Laird using the random-effects model[12]. A continuity correction of 0.5 was added to the number of incident cases if incidence of an outcome was zero before statistical analysis[13]. Heterogeneity was evaluatedviaCochraneQstatistical test for heterogeneity and theI2statistics[14,15].I2values of < 30%, 30% to 60%, 61% to 75%, and > 75% were indicative of low, moderate, substantial, and significant heterogeneity, respectively[16]. Publication bias was determined quantitativelyviathe Egger test and qualitativelyviavisual inspection of the funnel plot[17]. With the presence of publication bias, we used the fail-safe N test and the Duval and Tweedie’s “Trim and Fill” test to determine the impact of the bias[18]. Impact was described in three levels based on similarities between the reported results and of those estimated as if there were no bias. Impact was classified as minimal if versions of both results were valued to be same, modest if there was substantial change in effect size, but the conclusion remained the same, or severe if the final conclusion of the analysis was subject to change by the bias[19].

All of our analyses were executed using comprehensive meta-analysis software, version 3 (BioStat, Englewood, NJ, United States).

Outcomes assessed

Primary outcomes:(1) Pooled technical success rate of POP-guided lithotripsy; and (2) Pooled clinical success rate of POP-guided lithotripsy.

Secondary outcomes:(1) Pooled technical success rate: EHL and LL; (2) Pooled clinical success rate: EHL and LL; (3) Pooled rate of adverse events (AE): POP, EHL and LL; and (4) Pooled rate of AE subtypes for POP: Hemorrhage, post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP), perforation, abdominal pain, fever and infections.

Definition of outcomes

Technical success rate was defined as the rate of clearing the pancreatic duct stones[2,7-9,20-31]. Clinical success was defined as improvement of the symptoms, primarily pain[2,7,20-26,28-31]. AE was defined as complications directly related to the procedure.

RESULTS

Search results and characteristics of the population

Our initial search yielded 361 results. There was a total of 16 studies that reported on POP lithotripsy procedures. Ten of these studies reported outcomes on POP using EHL[2,7-9,20,21,23,25,29,30]and 8 studies reported outcomes on POP using LL[2,20,21,24,26-28,31].

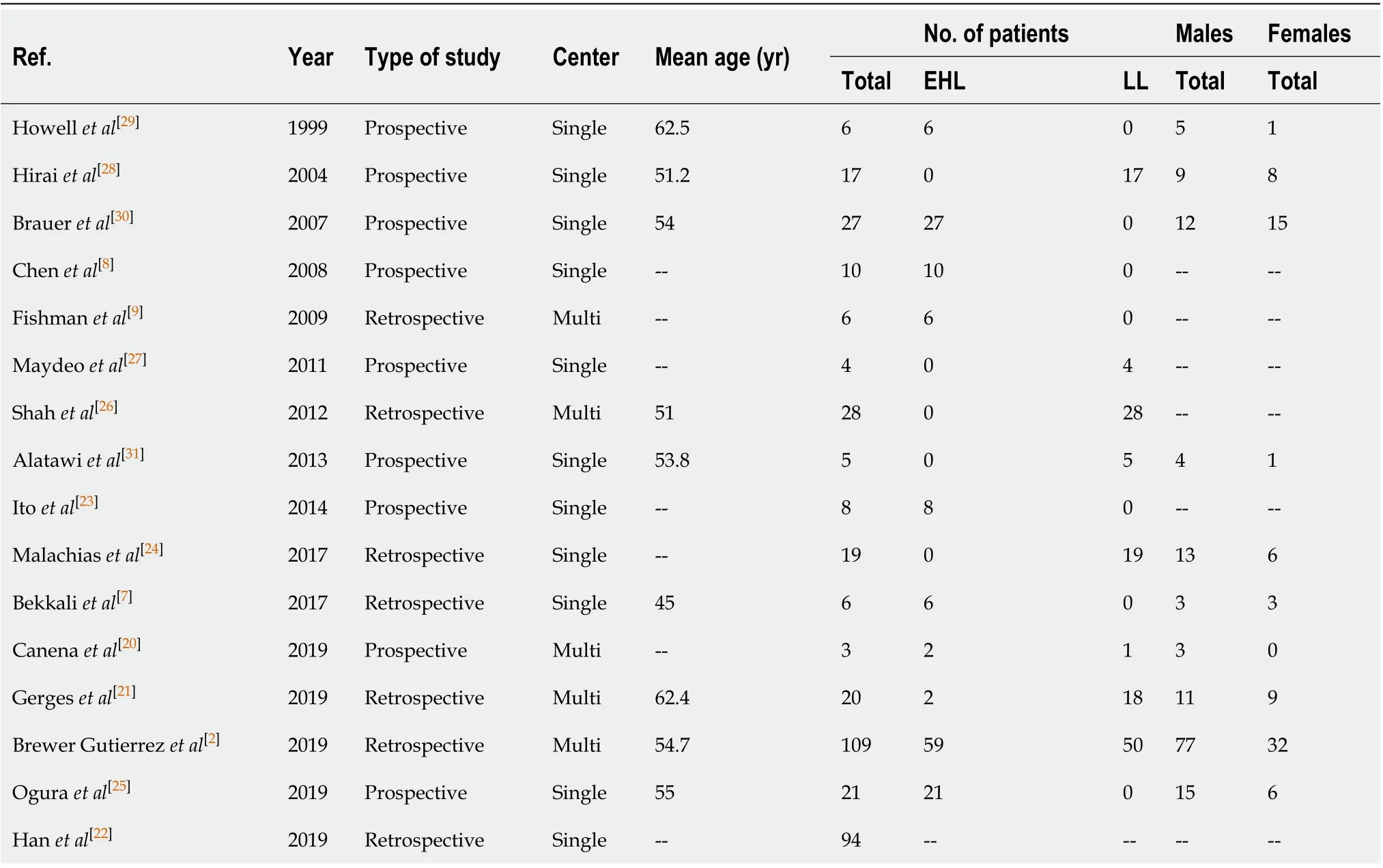

Ten of the 16 studies reported gender differences, with 65% of the population being male. The mean age reported in 9 of the 16 studies on POP was 54.4 years. The patient demographics are shown in Table 1.

Characteristics and quality of included studies

Nine studies were prospective, and the rest were retrospective. Eleven studies were from a single center and the remainder from multicenters. Twelve studies were in full text and 4 studies were in abstract form. There were no population-based studies. The clinical outcomes from all studies were adequately documented.

Outcomes of the meta-analysis

A total of 383 patients underwent 464 POP procedures. One hundred and forty-seven patients underwent 265 EHL procedures. One hundred and forty-two patients underwent 199 LL procedures.

Primary outcomes

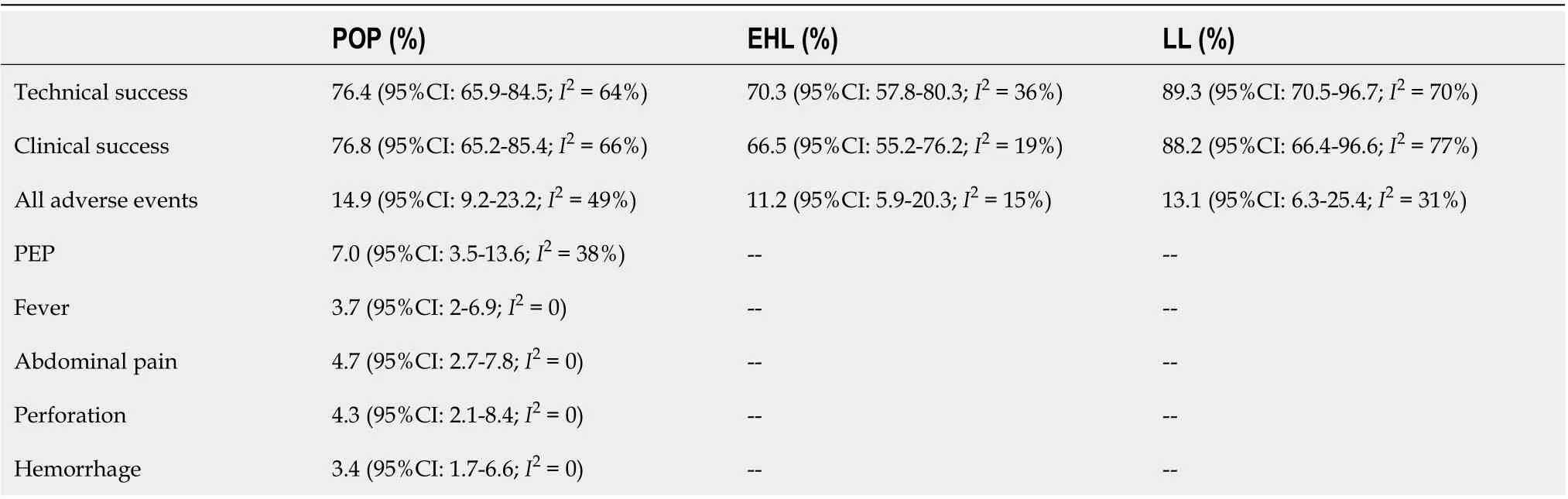

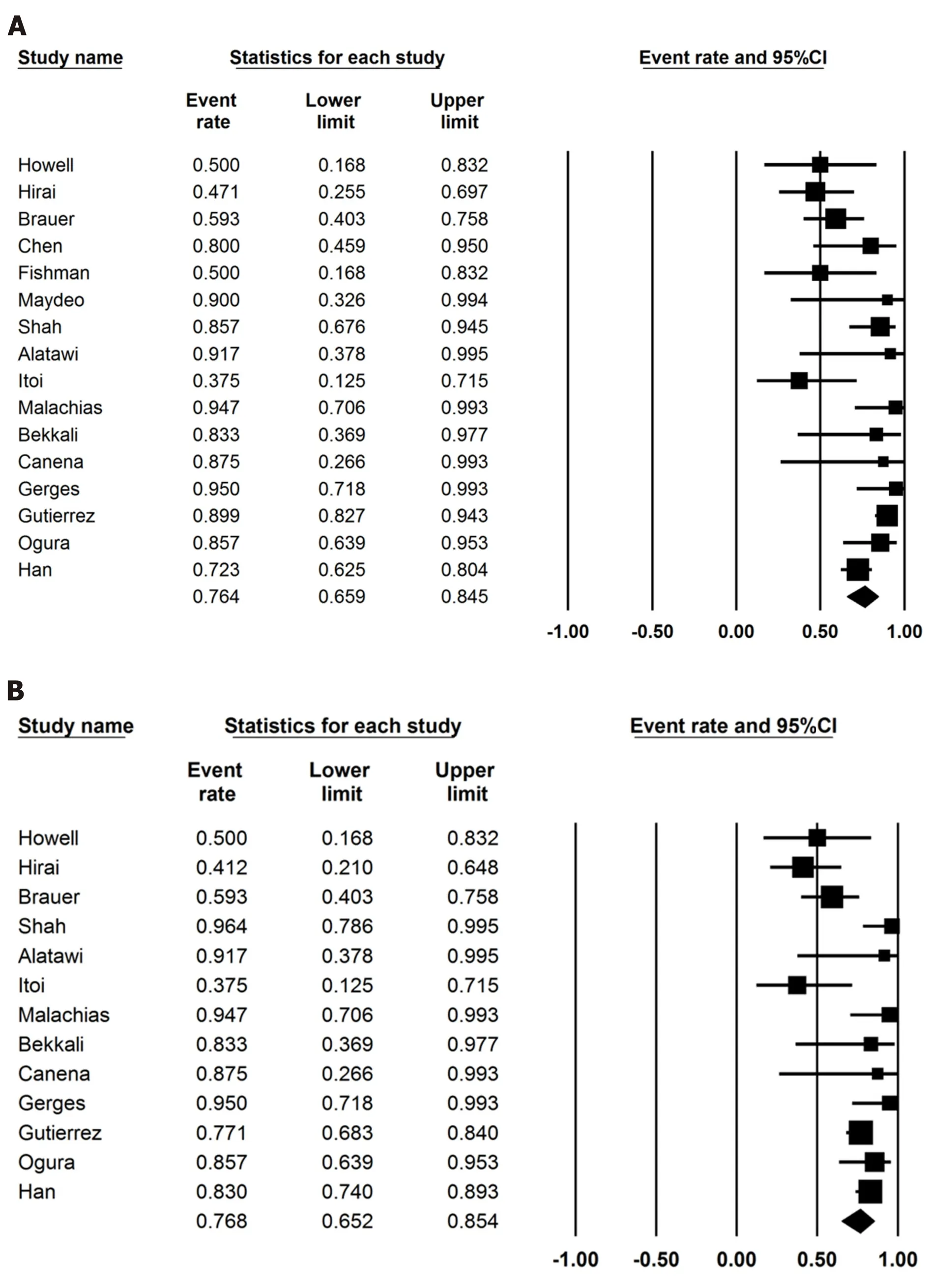

The pooled technical success rate of POP was 76.4% (95%CI: 65.9-84.5;I2= 64%) and the pooled clinical success rate of POP was 76.8% (95%CI: 65.2-85.4;I2= 66%). Figure 2 shows the forest plots for technical and clinical success of POP, respectively.

Secondary outcomes

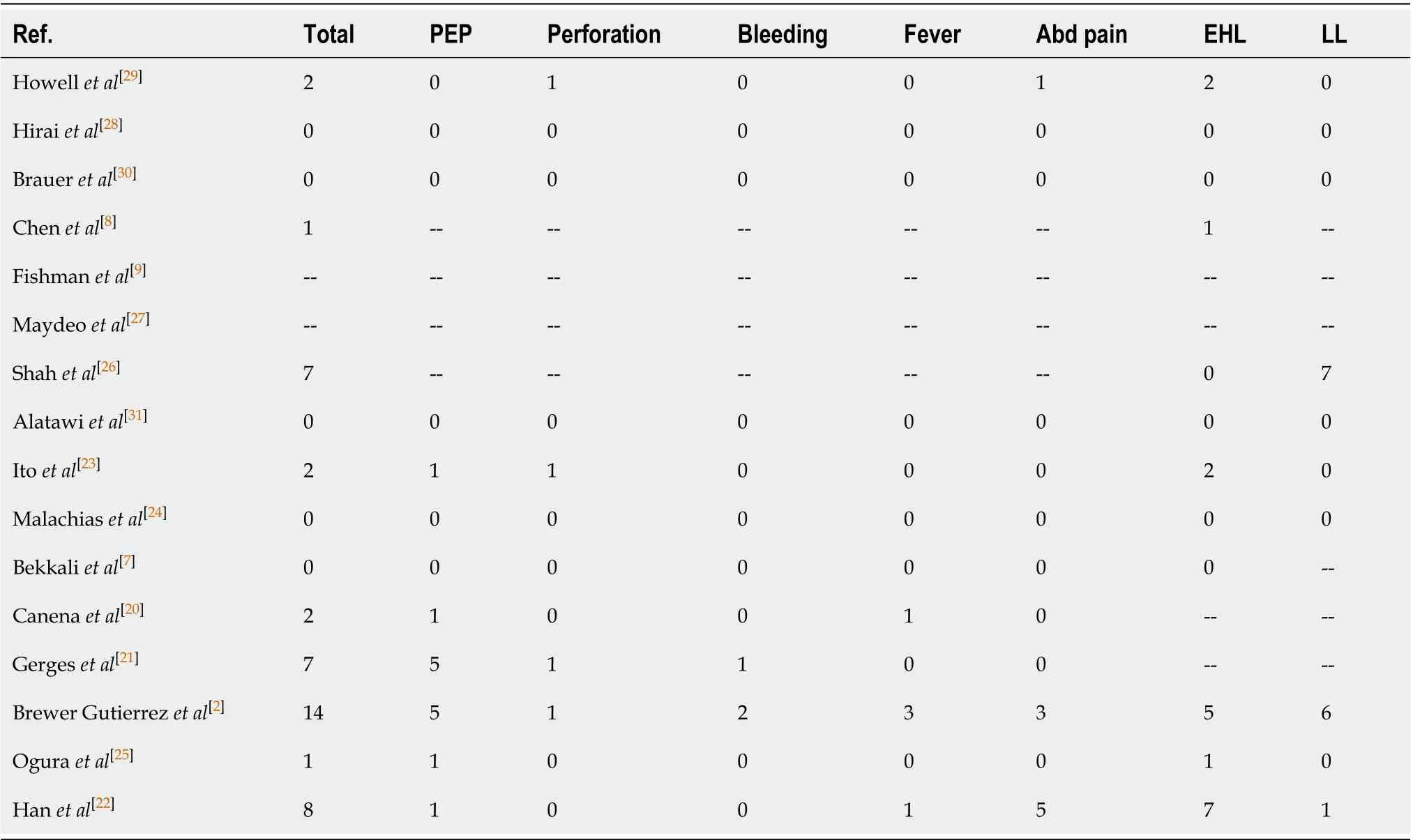

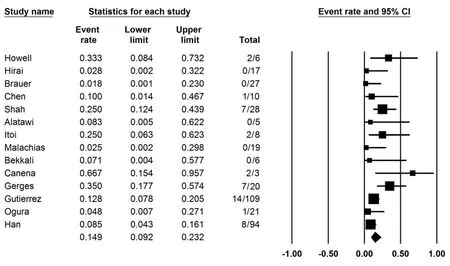

The pooled technical success rate of EHL was 70.3% (95%CI: 57.8-80.3;I2= 36%) and the pooled technical success rate for LL was 89.3% (95%CI: 70.5-96.7;I2= 70%). The pooled clinical success rate of EHL was 66.5% (95%CI: 55.2-76.2;I2= 19%) and of LL was 88.2% (95%CI: 66.4-96.6;I2= 77%). The pooled rates of technical success, clinical success, AE of POP, EHL and LL are presented in Table 2. The pooled POP AE rate was 14.9% (95%CI: 9.2-23.2;I2= 49%), the pooled POP EHL AE rate was 11.2% (95%CI: 5.9-20.3;I2= 15%) and the pooled POP LL AE rate was 13.1% (95%CI: 6.3-25.4;I2= 31%). The subgroup analysis for POP AE were as follows: post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP), 7% (95%CI: 3.5-13.6;I2= 38%); fever, 3.7% (95%CI: 2-6.9;I2= 0); abdominal pain, 4.7% (95%CI: 2.7-7.8;I2= 0); perforation, 4.3% (95%CI: 2.1-8.4;I2= 0); hemorrhage, 3.4% (95%CI: 1.7-6.6;I2= 0) and no mortality. The AE in all procedures is shown in Table 3. Figure 3-5 show technical and clinical success of EHL, technical and clinical success of LL, and total adverse events, respectively.

Validation of meta-analysis results

Sensitivity analysis:We excluded one study at a time and explored its effect on the main summary evaluation to determine if any one study had a dominant effect on the meta-analysis. We concluded that there was no significant effect on the outcome or heterogeneity.

The subgroup analysis of technical and clinical success by geographical location (United States, Japan and Europe), publication type (manuscript/abstract), study center (single/multicenter), and study type (retrospective/prospective) did not revealmajor differences.

Table 1 Description of 16 studies included in the final analysis

Table 2 Pooled rates of technical success, clinical success, and adverse events of per oral pancreatoscopy, electrohydraulic lithotripsy and laser lithotripsy

Heterogeneity:Based on prediction interval andI2analysis for heterogeneity, we assessed dispersion of the calculated rates. WithI2we can determine what proportion in terms of dispersion is truevschance[32]. The technical success of POP, clinical success of POP and technical success of LL showed substantial heterogeneity. The technical success in EHL, POP AE, POP LL AE, and PEP showed moderate heterogeneity. Clinical success in EHL, POP EHL AE and remaining subgroup analysis of AE had low heterogeneity. Clinical success for LL had significant heterogeneity.

Table 3 Adverse events in all procedures

Publication bias

Based on the results of the funnel plot and Eggers regression test, there was publication bias. Further assessment using the fail-safe N test and the Duval and Tweedie’s “Trim and Fill” test did not affect the final pooled outcomes. Figure 6 shows the funnel plot.

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates that the technical success rate of POP was 76.4% and the clinical success rate was 76.8%. Eight out of 16 studies performed ESWL[2,21-23,26,29,30]and all studies attempted standard ERCP prior to POP. This highlights that POP-guided lithotripsy can be utilized when patients fail in the first-line therapy.

The overall technical success ranged from 37.5%-95% and this variability could be secondary to the type of POP procedure used and the experience of the individual operator. On indirect comparative analysis between EHL and LL, we found that LL had higher overall rates of technical and clinical success. This may be secondary to the ability of LL to fragment denser stones (i.e., Hounsfield index > 2000 HU) as compared to EHL[2]. Although EHL is more widely available as compared to LL, LL tends to be much more expensive and requires special precautions compared with EHL. On subgroup analysis, studies with more than 20 patients showed higher technical success as compared to studies with less than 20 patients. This indicates that operator expertise may have influence on technical success.

Multiple stones, strictures, impacted stones, difficulty in cannulating PD due to angulation, poor visibility, equipment failure, or stones greater than 17 mm are other factors that may lead to lower technical success of POP[2,7,9,22-24,28-30]. Gutierrezet al[2]reported that presence of 3 or more stones was an independent risk factor for technical failure of POP (P< 0.04). Conversely, Hanet al[22]reported that increased stone burden lead to higher technical success as these patients had higher chances of having smaller stones as compared to larger stones, which led to easier clearance.

Only Gergeset al[21]reported data regarding quality of lifeviaquestionnaires for pre- and post-procedure pain improvement based on a numeric rating scale decreased from mean of 5.4 ± 1.6 to 2.8 ± 1.8 (P< 0.01). Improvement in quality of life was reported by 89% of the patients in this study, which is comparable to ESWL[21,33].

Figure 2 Per oral pancreatoscopy. A: Forest plot for the technical success of per oral pancreatoscopy; B: Forest plot for the clinical success of per oral pancreatoscopy.

The overall pooled AE rate of POP was comparable to ESWL ranging from 7% to 15%[34-37]. On subgroup analysis, the pooled AE rate of EHL and LL was similar at 11.2% and 13.1%, respectively. PEP was the most common AE and was comparable to ESWL at 7%[4,33,35].

Several limitations exist in our meta-analysis. Most of our studies were performed in tertiary care referral centers, so they may not be reflective of outcomes seen with less experienced operators. Also, POP does not reflect the skill of an average endoscopist. Our analysis contains studies that are retrospective in nature, which contribute to selection bias. No studies included data to compare POP as a first-line therapy with POP as a second-line therapy. Less than 5% of patients underwent POP as a first-line procedure and the individual outcomes were not mentioned in these studies. Nevertheless, this study contains the best available literature thus far with respect to POP. More studies are warranted to evaluate the technical and clinical success of EHL and LL. Clinical success is best defined universally with questionnaires, scores or scales to assess improvement of pain and quality of life, but not all studies provided this data.

Figure 3 Electrohydraulic lithotripsy. A: Forest plots showing technical success of electrohydraulic lithotripsy; B: Forest plots showing clinical success of electrohydraulic lithotripsy.

CONCLUSION

In summary, POP-guided lithotripsy is a viable option for management of patients with chronic pancreatitis and symptomatic PD stones. We found LL technique to have a higher technical and clinical success rate with comparable AE rates. Optimal techniques for POP should be selected based on the clinical situation, device availability, and local center expertise. Further randomized controlled trials are needed for head to head comparison of the two techniques and evaluate if POP can be a potential first-line therapy in these cases.

Figure 4 Laser lithotripsy. A: Forest plots showing technical success of laser lithotripsy; B: Forest plots showing clinical success of laser lithotripsy.

Figure 5 Forest plots for adverse events.

Figure 6 Funnel plots for publication bias.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research perspectives

Further randomized controlled trials are needed for head to head comparison of the two techniques and evaluate if POP can be a potential first line therapy in these cases.

猜你喜欢

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Role of succinate dehydrogenase deficiency and oncometabolites in gastrointestinal stromal tumors

- Acupuncture improved lipid metabolism by regulating intestinal absorption in mice

- Experimental model standardizing polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel to simulate endoscopic ultrasound and endoscopic ultrasound-elastography

- Construction of a convolutional neural network classifier developed by computed tomography images for pancreatic cancer diagnosis

- Mixed epithelial endocrine neoplasms of the colon and rectum – An evolution over time: A systematic review

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for Budd-Chiari syndrome: A comprehensive review