The selection rules of acupoints and meridians of traditional acupuncture for postoperative nausea and vomiting: a data mining-based literature study

2020-06-29LiShaLiuJianHuoXiuLiYuanYiLanJingYuanZhangHongMeiZhongYuWangYunShengHe

Li-Sha Liu, Jian Huo, Xiu-Li Yuan, Yi Lan, Jing-Yuan Zhang, Hong-Mei Zhong, Yu Wang, Yun-Sheng He

The selection rules of acupoints and meridians of traditional acupuncture for postoperative nausea and vomiting: a data mining-based literature study

Li-Sha Liu1*#, Jian Huo2#, Xiu-Li Yuan1, Yi Lan1, Jing-Yuan Zhang1, Hong-Mei Zhong1, Yu Wang3, Yun-Sheng He1

1Mianyang Affiliated Hospital, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Mianyang, 621000, China;2Chengdu Women's and Children's Central Hospital, School of Medicine, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, 611731, China;3Sichuan Second Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital, Chengdu, 610031, China.

: Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) refers to a problem commonly occurring after surgery. Acupuncture is considered a critical complementary alternative therapy for PONV. The acupoints selection critically determines the efficacy of acupuncture, whereas the selection rules remain unclear. The objective of the present study was to delve into the principles of acupoints selection for PONV using data mining technology.: Theclinical trials assessing the acupuncture effect for PONV were searched with the use of computer in PubMed, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, and Chinese Biomedical Database; the time span was confined as 2009–2019. The database of acupuncture prescriptions for PONV was built using Excel 2016; the description and association were analyzed by IBM SPSS modeler 18.: Eighty-three relevant literatures were screened out. The number of specific acupoints took up 72.5% of all acupoints; specific acupoints exhibited the frequency taking up 91.30% of the total frequency. As revealed from the result,Neiguan (PC 6), Zusanli (ST 36), Hegu (LI 4), andZhongwan (CV 12) were most frequently applied, suggesting the tightest associations. Most acupoints were taken from the stomach meridian and pericardium meridian. The common acupoints were concentrated in the lower limbs, chest, as well as abdomen.: Data mining acts as a feasible method to identify acupoints selection and compatibility characteristics. As suggested from our study, the acupoints selection for PONV prioritizes specific acupoints and related meridians. The selection and combination of acupoints comply with the theory of traditional Chinese medicine.

Postoperative nausea and vomiting, Acupuncture, Data mining, Regularity, Clinical research

The present study collected the clinical researches regarding acupuncture for postoperative nausea and vomiting in the recent decade and explored the selection rules based on data mining technology, to give scientific guide and evidence to clinical researchers.

The acupoints selection principles for nausea and vomiting was initially documented in the book() (221 B.C.E.–220 C.E.), valuably inspiring doctors of later generations. As revealed from the book() of Mi Huangpu in 282 C.E., nausea and vomiting displayed associations with the Zangfu (the general name of human internal organs in traditional Chinese medicine theory) and 18 core acupoints to treat nausea and vomiting were developed. In the 1950s, JF Xu adopted acupuncture at Neiguan (PC 6), Tianshu (ST 25) and chewed ginger to achieve nausea and vomiting treatment. In 1997, National Institutes of Health confirmed the role of acupuncture to treat nausea and vomiting. The mechanism of acupuncture may display associations with the enhancing effect on gastric motility and suppressing effect on temporary lower esophageal sphincter relaxation. The acupoints selection refers to the fundamental step of the effect, whereas the selection rules for postoperative nausea and vomiting remain unclear.

Background

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is defined as nausea or vomiting in 24 h postoperatively, one of the commonest complications after surgery or general anesthesia[1]. PONV is likely to cause numerous complications for patients (e.g., aspiration, wound dehiscence, hematoma, bleeding, dehydration, and electrolyte imbalance) [2]. The incidence of PONV follows the range from 20% to 30% in general patients and even up to 80% of the patients having undergone laparoscopic surgery [3]. PONV can adversely affect the rehabilitation after surgery and noticeably prolong the hospitalization length. In several cases, PONV might even induce mental symptoms (e.g., depression and anxiety) [4]. PONV has now aroused extensive attention from the researchers worldwide [5–7].The typical antiemetic drug, ondansetron, has been extensively used after surgery, whereas it brings the side effects (e.g., headache, constipation and abdominal pain) [8].

According to the history of acupuncture, the acupoints selection principles for nausea and vomiting was initially documented in the book[9] () (221 B.C.E.–220 C.E.). As highlighted, the nausea and vomiting should be treated by acupuncture at Zusanli (ST 36) as well as bleeding at the gallbladder meridian, valuably inspiring doctors of later generations. As revealed from the book[10]() of Mi Huangpu in 282 C.E., nausea and vomiting displayed associations with the Zangfu (the general name of human internal organs in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM)), and 18 core acupoints to treat nausea and vomiting were developed. As the modern medicine has been leaping forward, acupuncture therapies to treat nausea and vomiting have been extensively performed clinically. In the 1950s, JF Xu [11]adopted acupuncture at Neiguan (PC 6), Tianshu (ST 25) and chewed ginger to achieve nausea and vomiting treatment. In 1997, National Institutes of Health confirmed the role of acupuncture to treat nausea and vomiting [12]. The mechanism of acupuncture for PONV remains unclear. According to several studies, the mechanism of acupuncture might display associations with the enhancing effect on gastric motility and suppressing effect on temporary lower esophageal sphincter relaxation [13]. The acupoints selection refers to the fundamental step of the effect, whereas the selection rules for PONV remain unclear. Nevertheless, as fueled by the development of data mining, researchers are allowed to use novel methods to investigate the information of acupuncture. Data mining, i.e., knowledge discovery in databases, is considered the nontrivial extraction of implicit, previously unknown and potentially valuable data[14]. To give evidences to clinical researchers, the present study collected the clinical researches regarding acupuncture for PONV in the recent decade and explored the selection rules based on data mining technology.

Materials and methods

Data sources

The following databases were searched by computer: PubMed (http://www.pubmed.com), China Biomedical Database (http://www.sinomed.ac.cn), and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (http://www.cnki.net) for the period from 2009 to 2019. The searching target was confined into the modern literatures regarding traditional acupuncture for PONV. Besides, the language was set as English and Chinese.

Literature search strategy

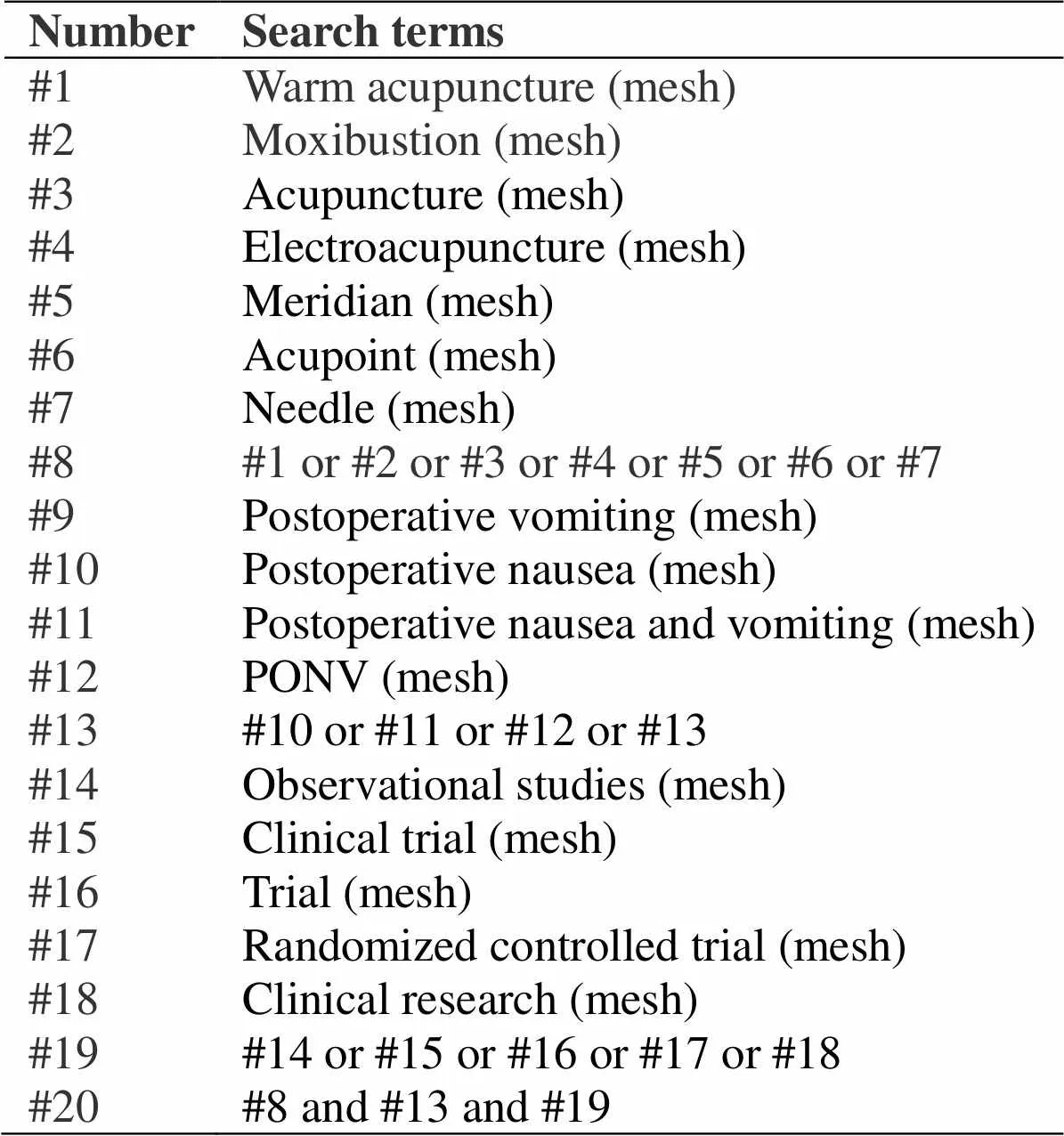

The subject words were searched in accordance with the name of disease and conventional acupuncture treatments. The searching mechanism of PubMed included: (warm acupuncture OR moxibustion OR acupuncture OR electroacupuncture OR meridian OR acupoint OR needle) AND (postoperative vomiting OR postoperative nausea OR postoperative nausea and vomiting OR PONV) AND (observational studies OR clinical trial OR trial OR randomized controlled trial OR clinical research), with unlimited subheadings. Similar search strategies were used in other databases. English medical subject words were referenced from the[15]and limited to “postoperative nausea and vomiting”. Chinese medical subject words were referenced from the Chinese translation of theand limited to “手术后恶心呕吐” (postoperative nausea and vomiting). Table 1 presents the retrieval strategy for PubMed.

Data screening

Types of studies. Inclusion criteria covered clinical trials that assess the effect of acupuncture for PONV, clinical trials with or without randomization and/or control can be covered. The latest one literature was selected for duplicate publications of the identical author. Participants with nausea and vomiting after operation were the research objects. Exclusion criteria consisted of reviews, animal trials, case reports, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses.

Types of intervention.Inclusion criteria covered clinical trials with acupuncture as the primary therapies. Acupuncture and moxibustion can be adopted independently or jointly with other types of interventions. Traditional acupuncturetherapies included: needle insertion into traditional meridian acupointsandextraordinaryacupoints;electric stimulation of needle insertion into acupoints or meridians; moxibustion; simultaneous intervention of acupuncture/electroacupuncture and moxibustion.Exclusion criteria consisted of trials of stimulating Ashi acupoint (a kind of acupoint that you will feel pain when pressing it) alone; trials of dry needling or trigger point therapy complying with anatomy and physiology; trials of laser acupuncture and non-invasive electrical stimulation (e.g., transcutaneous acupoint electrical stimulation); acupoint massage (finger-pressing acupoint); studies assessing micro-acupuncture for different theoretical basis from TCM [16]. The focus of this trial is limited to traditional acupuncture by screening therapies.

Table 1 The retrieval strategy for PubMed

Types of outcome measurements.The following was the inclusion criteria. Studies were covered if reporting at least one clinical outcome regarding PONV (e.g., nausea, vomiting, abdominal distention, abdominal pain, and use of antiemetic drugs). In the case of controlled trials, acupoints selection without statistical improvement in symptoms could be incorporated into prescriptions. Several studies drew the comparison of the therapeutic effects of various acupoints. Only the prescriptions with optimal efficacy should be covered. The following was the exclusion criteria. Trials reported only physiological or laboratory parameters were excluded. Acupoint prescriptions were excluded except for the most feasible one if 1 study drew the comparison of the therapeutic effects of a range of prescriptions.

Data collection. All the titles and abstracts of respective record retrieved from the literature search screened by Lisha Liu. who excluded those noticeably unrelated abstracts (e.g., studies focusing on case reports reviews, experiments, animal), reviewed the full text of all potentially relevant articles, and then re-screened these articles to exclude the unrelated ones. Subsequently, Jian Huo made a formal check of the eligibility of all articles in accordance with the mentioned screening criteria. If differences existed between the 2 researchers, they decided to include or exclude the literatures given the discussion or after the third researcher reviewed the information. Literature information, covering title, author, journal name, intervention measures and results (e.g., number of acupoints, location of acupoints, meridians of acupoints, and specific acupoints) were standardized prior to processing. The names of acupoints were standardized in line with the basic principles of[17].

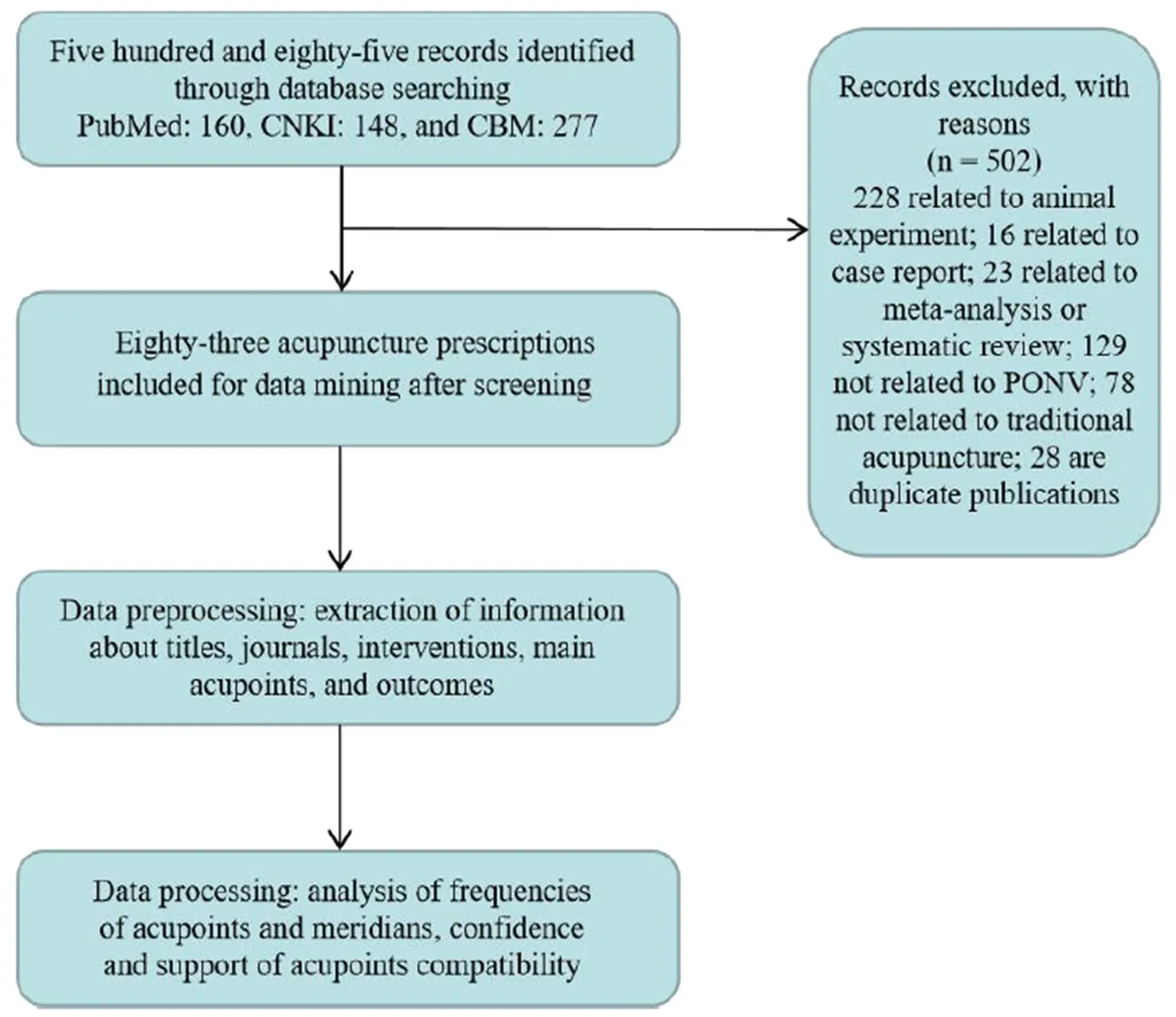

Data processing.The prescriptions of acupuncture for PONV were inputted into Microsoft Excel 2016. IBM SPSS modeler 18 was employed to calculate the frequency, support, confidence, as well as lift level [18]. Support refers to an index expressing the probability of event A and event B that appear simultaneously under specific conditions. Confidence refers to the probability of event B that appears in event A [19]. Lift displays the ratio of confidence for the rule to the prior probability of having the consequent [20]. On the whole, rules with lift different from 1 will be more noteworthy than those with lift close to 1. Lift indicates the ratio of confidence of the rule to the previous probability of generating the result. Association rules are useful only when the support degree and confidence level satisfy the minimal requirements. Apriori algorithm, a common algorithm to mine association rules, was adopted to analyze the frequencies and support of acupoint combinations. Given the definition of association rules mining [21], the following can be a statement to mine association principles for acupoint combination. Set I = {i 1, i 2, …, i m} as a set of acupoints. Set D as a group of acupoint prescriptions, in which each acupoint prescription T denotes a set of acupoints, so T ⊆ I. Each acupoint prescription is associated with a unique identifier, termed as TID. An acupoint prescription T covers X, a set of some acupoints in I, if X ⊆ T. The rule X–Y has support s in the acupoint prescription set D if s% of acupoint prescriptions in D contain X ⋃Y. Figure 1 presents the steps of data processing.

Results

Overall profile of acupuncture prescriptions

Database searching identified 160 records in PubMed, 148 records in China National Knowledge Infrastructure, and 277 records in Chinese Biomedical Database. Eighty-three acupuncture prescriptionswerecoveredinthepresentstudyafter filtering (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The steps of data processing. CNKI, China National Knowledge Infrastructure; CBM, Chinese Biomedical Database; PONV, postoperative nausea and vomiting.

Application of acupoints

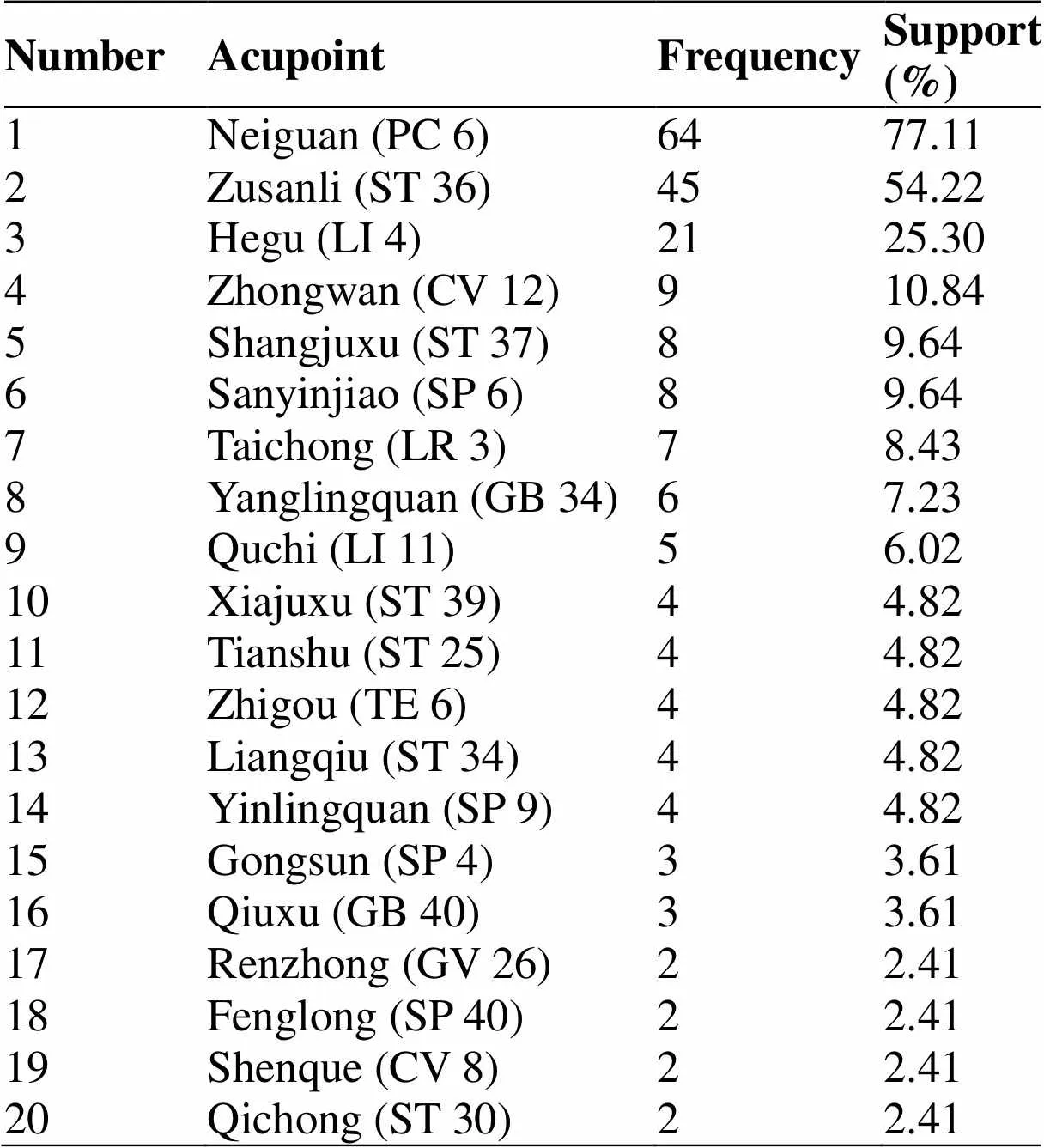

This analysis aimed to provide the acupoints selections and their frequencies when treating PONV by acupuncture. Statistics revealed that acupuncture prescriptions for PONV covered 40 acupoints in the whole body, and the total application frequency of the acupoints reached 230 times. The commonest acupoints for PONV in descending order included Neiguan (PC 6), Zusanli (ST 36), Hegu (LI 4), Zhongwan (CV 12), Shangjuxu (ST 37), Sanyinjiao (SP 6), Taichong (LR 3), Yanglingquan (GB 34), Quchi (LI 11) and Xiajuxu (ST 39) (Table 2).

Application of meridians

The taken acupoints displayed the distribution among 12 meridians, covering 10 regular meridians, governor vessel, and conception vessel. The commonest meridians included large intestine meridian (LI), pericardium meridian (PC), and stomach meridian (ST). Table 3 lists in the application of meridians.

Application of special acupoints

The number of specific acupoints took up 29 (72.50%) of the 40 acupoints, and the frequency (210 times) took up 91.30% of the total frequencies. Crossing acupoints were the commonest specific acupoints, exhibiting the frequency of 92 times. They were followed with Luo-connecting point, five-Mu point, eight-convergent points, lower He-sea point and Yuan-source point (they are the specific acupoints are a group of acupoints with particular treating effect on 14 meridians) (Table 4).

Specific acupoints refer to a group of acupoints with particular treating effect on 14 meridians. Specific acupoints consisted of ten types, namely, back-Shu points (the acupoints on the back where the Qi of Zangfu gathers), Xi-cleft points (the acupoints where the meridian Qi is deeply gathered), eight-confluent points (8 specific acupoints on the four limbs that connecting 8 extra meridians and the 12 regular meridians), front-Mu points (the acupoints located on the chest and abdomen where the Qi of Zangfu gathers), Yuan-source points (the acupoints located near the wrist or ankle where the Qi of Zangfu passes and gathers), lower He-sea points (the specific acupoints reflect the 6 Fu (viscera) in the lower limbs), eight convergent points (the 8 specific points located on the four limbs where the twelve meridians communicates with the eight extra channels), five-Shu points (the 5 acupoints located below the elbow and knee joints of the 12 regular meridians), Luo-connecting points (the acupoints linking the inner and outer meridians), crossing points (the acupoints where 2 or more meridians cross).

Application of acupoints on different body parts

Given the analysis and statistics of the location of acupoints, acupoints on the lower limbs have been used most frequently, with 11 acupoints and a frequency of 100 times in total, followed by acupoints on the chest and abdominal (used 25 times), back and lumbar (used 3 times), and the head, face, and neck (used 3 times) (Table 5).

Association of acupoint compatibilities

IBM SPSS Modeler 18 was employed for the analysis of the association rules of acupoints with frequencies 2 times or more. The minimal support degree was set to 10%, the minimal confidence level was set to 20%, and the maximal preceding item was set to 5. The support degree suggested that Hegu (LI 4)-Neiguan (PC 6), and Zusanli (ST 36)-Neiguan (PC 6) appeared together in the 83 prescriptions 77.11% of the time. The maximal confidence level was Zusanli (ST 36)-Zhongwan (CV 12), and Neiguan (PC 6)-Zhongwan (CV 12), revealing that when Zusanli (ST 36) and Neiguan (PC 6) appeared, the probability of Zhongwan (CV 12) was 88.89%. Lift was different from 1, revealing that the results were reliable. Table 6 lists the 21 most commonly used acupoint combination, support, and confidence, and Figure 2 presents the network map according to the combination result.

Table 2 Twenty commonest acupoints identified by data mining

Table 3 Meridians and acupoints used in acupuncture therapy for postoperative nausea and vomiting

Frequencies of meridians mean that the total frequency of acupoints on the same meridian; PCT indicates the percentage of a specific meridian frequency taking up the total frequency of all meridians. The number of acupoints represents the total number of selected acupoints on the same meridian. PCT of acupoints indicates the percentage of number of acupoints taking up the total number of taken acupoints in all meridians.

ST, stomach meridian, PC, pericardium meridian, LI, large intestine meridian, SP, spleen meridian, GB, gallbladder meridian, LR, liver meridian, TE, triple energizer, BL, bladder meridian; LU, lung meridian; HT, heart meridian, CV, conception vessel, GV, governor meridian; PCT, percent.

Table 4 Frequencies and numbers of different types of acupoints

Table 5 The frequencies and numbers of acupoints on different body parts

Table 6 Combinations of the 21 commonest acupoints

Figure 2 Network map of acupoint combinations

Discussion

Patients are now inclined to look for less harmful, more acceptable, and more feasible therapies [22]. In the present paper, the clinical literatures of acupuncture for PONV were searched, and the following rules of acupoints selection were identified based on data mining technology.

Application of meridian and acupoints for PONV

According to the results of acupoint location analysis, acupuncture for PONV is characterized by selecting acupoint according to the disease location. The sites of acupoints concentrated in the lower limb, chest and abdomen. PONV belongs to the category of “epigastric fullness” and “vomiting” in TCM, locating in the stomach. According to modern research, acupoints selection complying with the location of disease is capable of stimulating the nearby acupoints to exert a good target effect, e.g., taking Tianshu (ST 25) to treat abdominal disease, taking Baihui (GV-20) to treat head disease, and Zusanli (ST 36) to treat knee joint disease[23]. The absorption function of small intestine was reported to be enhanced, and the content of D-xylose in serum was up-regulated after electroacupuncture at Zhongwan (CV 12) and Tianshu (ST 25) in rats with functional diarrhea [24]. Acupoints selection for PONV complies with the fundamental rule of “the location of acupoints is the range of indications” in TCM theory. The results of meridians analysis suggest another rule that “selecting acupoints in line with the meridians involved in the disease”. The main acupoints were from ST and PC, the frequency percentages of the 2 meridians were 30.00% and 27.83%, respectively. The direction of ST is from head to foot, following the stomach. PC originates is from the chest, going through the heart, chest, and stomach. Modern clinical researches suggested that the treating effect of acupoints of ST for functional dyspepsia were significantly better than acupoints of other meridians [25]. A number of experimental studies also verified the specificity effect of a range of meridians, the rats received ligation of SThad defecation and diet changes, remarkably different from those received ligation of other meridians [26]. The acupuncture for PONV complies with the principle of selecting acupoints in theory of TCM, as well as with the basic law that “the indication extends to where the meridian reaches”.

Acupoint compatibility in treatment of PONV

Acupoints exhibit specificity in morphological structure, biophysical characteristics, pathological response and stimulation; such specificity is capable of distinguishing acupoints and non-acupoints[27]. Accordingly, the proper selection of acupoints is critical to the treating effect of acupuncture for PONV. Specific acupoints are a group of acupoints with specific treating effect on 14 meridians. There are 10 types of specific acupoints, namely, crossing points, Luo-connecting points, five-Mu points, eight convergent points, lower He-sea points, Yuan-source points, front-Mu points, Xi-cleft points, back-Shu points. The result revealed that the specific acupoints took up 72.50% of the total number of acupoints. Neiguan (PC 6) and Zusanli (ST 36) were the most commonly used specific acupoints. According to the attribution of specific acupoints, Neiguan (PC 6) was the acupoint with the maximal frequency, which is one of the Luo-connecting points and eight confluent points of PC. Zusanli (ST 36) is one of the lower He-sea points of ST. According to the analysis of the compatibility, the combination of Neiguan (PC 6), Zusanli (ST 36), Hegu (LI 4), Zhongwan (CV 12) might has the potential for PONV. Most prescriptions of acupuncture for PONV included acupoint combinations while few of them cover single acupoint. For instance, patients received acupuncture at Neiguan (PC 6) and Hegu (LI 4) displayed a lower incidence of PONV in contrast to the patients received acupuncture at Neiguan (PC 6) [28]. Clinical studies also revealed that electroacupuncture on Neiguan (PC 6) and Zusanli (ST 36) for 30 min before anesthesia could effectively reduce PONV, and the plasma concentration of serotonin[29]. One study reported that there were somatic visceral convergent neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the inferior colliculus, capable of responding to both gastric distensible and acupuncture stimulation, probably associating with the regulatory effects of Neiguan (PC 6) andZusanli (ST 36) for gastrointestinal function [30]. Electroacupuncture at Zusanli (ST 36) was reported to be able to suppress stress through receptor type 1 of corticotropin releasing factor and relieve delayed gastric emptying via receptor type 2 of corticotropin releasing factor, thereby facilitating colonic transport and relieving gastrointestinal conduction disorder after abdominal operation[31]. Nevertheless, several experiment-based studies have reported antagonistic effects that one acupoint weakens the treating effect of another. For instance, electroacupuncture could improve gastrointestinal motility in rats, while the effect of single acupuncture at Pishu (BL 20) was better than that of simultaneous at Pishu (BL 20) and Zusanli (ST 36) [32]. Moxibustion at Zusanli (ST 36) was reported to be able to noticeably enhance gastric motility of rats at the temperature of thermal stimulation as 43°C and 45 °C, while moxibustion at Zhongwan (CV 12) could inhibit gastric motility at the identical temperature level [33]. Accordingly, whether the acupoint combination outperforms single acupoint require in-depth studies.

Limitations

First, the evidence-based medicine method based on randomized control in many literatures included in the present study was not available, so the present study did not assess the quality of the included literatures. The uneven quality of the literatures may affect scientific and objective outcomes. Second, some literatures did not report specific operations, treatment frequency and treatment time, so the present study did not analyze these information, requiring in-depth studies. Lastly, preoperative or postoperative intervention of acupuncture remains controversial and the optimal intervention time remains unclear. According to the mentioned results, potential acupoints and combinations will be explored in future clinical trials to verify the effects of acupuncture for PONV. The data can be extracted not only from literatures, but also from clinical practices and optimized acupoint prescription by data mining in the future.

Conclusions

In the present study, data mining was employed to identify the commonest acupoints, meridians, specific points, as well as the acupoints combination of acupuncture for PONV. The commonest acupoints were Neiguan (PC 6), Zusanli (ST 36), and Hegu (LI 4). The commonest meridians were ST, PC, and LI. Acupoints used were primarily specific acupoints, and the acupoints on the lower limbs. As revealed from the findings here, Neiguan (PC 6), Zusanli (ST 36), Hegu (LI 4), and Zhongwan (CV 12) require in-depth investigation in forthcoming trials or employed clinically for PONV.

Data Availability

Some or all data, models, or code generated or used during the study are available in a repository or online in accordance with funder data retention policies. DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.10171304.

1. Matthews C. A review of nausea and vomiting in the anaesthetic and post anaesthetic environment. J Perioper Pract 2017, 27: 224–247.

2. Apfel CC, Heidrich FM, Jukar-Rao S, et al. Evidence-based analysis of risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Br J Anaesth 2012, 109: 742–753.

3. Gan TJ, Diemunsch P, Habib AS, et al. Consensus guidelines for the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg 2014, 118: 85–113.

4. Chatterjee A, Rudra A, Sengupta S. Current concepts in the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesiol Res Pract 2011, 74: 1–10.

5. Majholm B, Møller AM. Acupressure at acupoint P6 for prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: a randomised clinical trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2011, 28: 412–419.

6. Chung YC, Tsou MY, Chen HH, et al. Integrative acupoint stimulation to alleviate postoperative pain and morphine-related side effects: a sham-controlled study. Int J Nurs Stud 2014, 51: 370–378.

7. Kwon JH, Shin Y, Juon HS. Effects of Nei-Guan (P6) acupressure wristband: on nausea, v- omiting, and retching in women after thyroidectomy. Cancer Nurs 2016, 39: 61–66.

8. Goodin S, Cunningham R. 5-HT (3)-receptor antagonists for the treatment of nausea and vomiting: a reappraisal of their side-effect profile. Oncologist 2002, 7: 424–436.

9. Lehmann H. Acupuncture in ancient China: how important was it really? J Integr Med 2013, 11: 45–53.

10. Pang B, Wang ZX. Contribution of() to surface anatomy. Chin Acup Moxib 2011, 31: 371–374. (Chinese)

11. Chang TAN, Weimin LU, Danhua XU, et al. Experience of Jingfan XU in Treating Postoperative Esophageal Cancer. J Tradit Chin Med 2019, 60: 195–198. (Chinese)

12. Morey SS. NIH issues consensus statement on acupuncture. Am Fam Physician 1998, 57: 2545–2546.

13. Li H, He T, Xu Q, et al. Acupuncture and regulation of gastrointestinal function. World J Gastroenterol 2015, 21: 8304–8313.

14. Zhang Y, Guo SL, Han LN, et al. Application and exploration of big data mining in clinical medicine. Chin Med J 2016, 129: 731–738. (Chinese)

15. Lipscomb CE.(MeSH). Bull Med Libr Assoc 2000, 88: 265–266.

16. Li X, Sun Y, Xu X, et al. Present situation and development direction of microacupuncture therapy. Chin Acup Moxib 2016, 36: 557. (Chinese)

17. Luo YF, Wu JM. Fundamentals of Acupuncture. Sichuan: Sichuan University Press, 2008. (Chinese)

18. Wang C, Chen MH, Schifano E, et al. Statistical methods and computing for big data. Stat Interface 2016, 9: 399–414.

19. Samet A, Lefèvre E, Yahia SB. Evidential data mining: precise support and confidence. J Intell Inf Syst 2016, 47: 135–163.

20. Deora CS, Arora S, Makani Z. Comparison of interestingness measures: support-confidence framework versus lift-irule framework. Int J Eng Res Appl 2013, 3: 208–215.

21. Agrawal R, Imielinski T, Swami A. Mining association rules between sets of items in large databases. ACM SIGMOD Record 1993, 22: 207–216.

22. Veigagil L, Pueyo J, Lópezolaondo L. Postoperative nausea and vomiting: physiopathology, risk factors, prophylaxis and treatment. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 2017, 64: 223–232.

23. Zhao L, Chen J, Liu CZ, et al. A review of acupoint specificity research in china: status quo and prospects. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012, 2012: 543943.

24. Yin S, Chen Y, Lei D, et al. Cerebral mechanism of puncturing at He-Mu point combination for functional dyspepsia: study protocol for a randomized controlled parallel trial. Neural Regen Res 2017, 12: 831–840.

25. Han G, Ko SJ, Park JW, et al. Acupuncture for functional dyspepsia: study protocol for a two-center, randomized controlled trial. Trials 2014, 15: 89.

26. Ye FY. Observation of the effects of ligation of stomach, kidney and Du meridians on emotional cognition and related organs in rats. Beijing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2019. (Chinese)

27. Zhou W, Benharash P. Effects and mechanisms of acupuncture based on the principle of meridians. J Acupunct Meridian Stud 2014, 7: 190–193.

28. Pan F, Gong H, He B, et al. Preventive and therapeutic effects of different acupoints and stimulating methods on nausea and vomiting after breast surgery. J New Chin Med 2014, 46: 169–171. (Chinese)

29. Fleckenstein J, Baeumler P, Gurschler C, et al. Acupuncture reduces the time from extubation to “ready for discharge” from the post anaesthesia care unit: results from the randomised controlled AcuARP trial. Sci Rep 2018, 8: 15734.

30. Qin QG, Gao XY, Liu K, et al. Acupuncture at heterotopic acupoints enhances jejunal motility in constipated and diarrheic rats. World J Gastroenterol 2014, 20: 18271–18283.

31. Jung SY, Chae HD, Kang UR, et al. Effect of acupuncture on postoperative ileus after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. J Gastric Cancer 2017, 17: 11–20.

32. Zhu J, Xu Q, Zou R, et al. Distal acupoint stimulation versus peri-incisional stimulation for postoperative pain in open abdominal surgery: a systematic review and implications for clinical practice. BMC Complement Altern Med 2019, 19: 192.

33. Su YS, Xin JJ, Yang ZK, et al. Effects of different local moxibustion-like stimuli at Zusanli (ST 36) and Zhongwan (CV 12) on gastric motility and its underlying receptor mechanism. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015, 2015: 486963.

34. Agrawal R, Imielinski T, Swami A. Mining association rules between sets of items in large databases. ACM SIGMOD Record 1993, 22: 207–216.

:

This study was supported by the Major projects of Sichuan Science and Technology Department of China (No. 18ZDYF0347) and Mianyang Science and Technology Bureau of China (No. 17YFHM008).

:

PONV, postoperative nausea and vomiting; TCM, traditional Chinese medicine; ST, stomach meridian; PC, pericardium meridian; LI, large intestine meridian; GV, governor meridian.

:

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

:

Li-Sha Liu, Jian Huo, Xiu-Li Yuan, et al.The selection rules of acupoints and meridians of traditional acupuncture for postoperative nausea and vomiting: a data mining-based literature study. Traditional Medicine Research 2020, 5 (4): 272–281.

: Xiao-Hong Sheng

:23 December 2019,

11January 2020,

:16 January 2020.

#These authors are co-first authors on this work.

Li-Sha Liu.Mianyang Affiliated Hospital, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, No.14, Fucheng Road, Fucheng District, Mianyang, 621000, China. E-mail: wenliyinyusha@163.com.

10.12032/TMR20200114154

杂志排行

Traditional Medicine Research的其它文章

- Treating COVID-19 by traditional Chinese medicine: a charming strategy?

- India’s indigenous idea of herd immunity: the solution for COVID-19?

- Does Liuzijue Qigong affect anxiety in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, even during the COVID-19 outbreak? a randomized, controlled trial

- Qingfei oral liquid downregulates TRPV1 expression to reduce airway inflammation and mucus hypersecretion injury caused by respiratory syncytial virus infection and asthma in mice

- The advances of traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment of liver diseases in 2019

- Efficacy of Xuebijing injection for the treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 via network pharmacology