When Did Humans First Learn to Count?

2018-11-28孙加

The history of math is murky1murky模糊不清。,predating2predate早于。any written records.When did humans first grasp the basic concept of a number? What about size and magnitude3magnitude巨大 。,or form and shape?

数学的开端早于所有现存的书面记录,因而其历史模糊不清。人类何时开始掌握基本的数字概念?何时开始掌握大小和度量概念,或外形和形状概念?

[2]In my math history courses and my research travels in Guatemala,Egypt and Japan,I’ve been especially interested in the commonality4commonality共同点。and differences of mathematics from various cultures.

[2]我教授数学历史课程,为了做研究,去过危地马拉、埃及和日本。在授课和研究过程中,我对各个文化间数学的异同尤其感兴趣。

[3]Although no one knows math’s exact origins,modern mathematicians like myself know that spoken language precedes written language by scores of5scores of许多。millennia.Linguistic clues show how people around the world must have first developed mathematical thought.

[3]数学的确切起源无人知晓。但是,现代数学家(比如我自己)都清楚,口头语言的发端比书面语言要早几千年。从语言学中能找到线索,说明世界各地的人们最初是如何发展出数学思维的。

Early clues

早期线索

[4]Differences are easier to comprehend than similarities.The ability to distinguish more versus6versus(比较两种不同想法、选择等)与……相对,与……相比。less,male versus female or short versus tall must be very ancient concepts.But the con-cept of different objects sharing a common attribute7attribute特征。—such as being green or round or the idea that a single rabbit,a solitary8solitary孤零零的,离群的。bird and one moon all share the attribute of uniqueness—is far subtler.

[4]数学中的“不同”概念,比“相似”概念容易掌握。“多”和“少”,“男”和“女”,“矮”和“高”,人类很早就能区别这些概念。而“不同的物体拥有共同特征”这一概念则复杂得多——比如,都是绿色、都是圆形,或单只兔子、一只孤鸟和一轮明月都拥有“独一无二”这一特征。

[5]In English,there are many different words for two,like “duo,” “pair”and “couple,” as well as very particular phrases such as “team of horses”or “brace of partridge.” This suggests that the mathematical concept of twoness developed well after humans had a highly developed and rich language.

[5]英语中有很多词表示“双”的概念,例如duo、pair和couple,还有些很特别的短语,如team of horses(一同拉车的两匹马)、brace of partridge(打猎时射下的一对鹧鸪)。这表明,在人类语言高度发展和极大丰富很久以后,才有了“二”这个数学概念。

[6]By the way,the word “two” probably was once pronounced closer to the way it’s spelled,based on the modern pronunciation of twin,between,twain(two fathoms9fathom英寻(测量水深用的长度单位,合6英尺或1.829米)。fathom来自古英语fæthm,表示“伸展开的双臂”,因而1英寻也就是两臂之长。),twilight (where day meets night),twine (the twisting of two strands)and twig (where a tree branch splits in two).

[6]顺带一提,two一词原先的发音,很可能跟拼写方式相近。这一猜测,乃是基于现代英语中以下这些词的发音:twin(双胞胎)、between(在……之 间 )、twain( 水 深 两 寻 ),twilight(日夜之交)、twine(合股绞线)、twig(树枝分岔处)。

[7]Written language developed much later than spoken language.Unfortunately,much was recorded on perishable10perishable易损的,易腐的。media,which have long since decayed.But some ancient artifacts that have survived do exhibit some mathematical sophistication.

[7]书面语言比口头语言出现晚得多。不幸的是,很多书面记录都写在易损的介质上,腐烂已久。不过,也有些古代人工制品得以留存至今,可以看出数学的成熟发展。

[8]For example,prehistoric tally11tally(符契上的)刻记;计数的签筹。sticks—notches12notch(刻在棍子等上的)计数刻痕。incised13incise(在表面)雕;切入。on animal bones—are found in many locations around the world.Though these might not be proof of actual counting,they do suggest some sense of numerical record keeping.Certainly people were making one-to-one comparisons between the notches and external collections of objects—perhaps stones,fruits or animals.

[8]比如,全球很多地方都出土了史前文物“记数棒”——刻有计数痕迹的动物骨头。这些或许算不上真正计数的证据,但确实表明,史前人类有了保存数字记录的意识。当时的人类,肯定是拿着记数棒,与某种外部收集的物体(也许是石头、水果或动物)一对一比照计数。

Counting objects

计算物体数量

[9]The study of modern “primitive”cultures offers another window into human mathematical development.By“primitive,” I mean cultures that lack a written language or the use of modern tools and technology.Many “primitive”societies have well-developed arts and a deep sense of ethics and morals,and they live within sophisticated societies with complex rules and expectations.

[9]对现代“原始”文化的研究,也提供了一扇了解人类数学发展的窗口。我说的“原始”文化,是指没有书面语言或没有现代工具和技术的文化。很多“原始”社会有发达的艺术,深刻的伦理道德观,社会发展成熟,具备复杂的规范和要求。

[10]In these cultures,counting is often done silently by bending down fingers or pointing to specific parts of the body.A Papuan14巴布亚族,新几内亚的原住民。tribe of New Guinea15新几内亚,太平洋西南岛屿,澳大利亚以北。can count from 1 to 22 by pointing to various fingers as well as to their elbows,shoulders,mouth and nose.

[10]在这些文化中,人们计数时通常默不作声,只弯曲手指,或者指向身体的某个部位。新几内亚的某个巴布亚部落,计数时指向各个手指、手肘、肩膀、嘴巴和鼻子,用这种办法,能从1数到22。

[11]Most primitive cultures use object-specific counting,depending on what’s prevalent in their environment.For example,the Aztecs16Aztec阿兹特克人。阿兹特克是14—16世纪的墨西哥古文明。would count one stone,two stone,three stone and so on.Five fish would be “five stone fish.”Counting by a native tribe in Java begins with one grain.The Nicie tribe of the South Pacific counts by fruit.

[11]很多原始文化使用“物体计数法”。其中的“物体”各有不同,取决于在当地环境中,什么东西最为普遍。例如,阿兹特克人计数时,会数“1石头、2石头、3石头”,等等。“5条鱼”在阿兹特克人说来,就是“5石头鱼”。另外,爪哇的某个原住民部落,从“1谷”开始计数;南太平洋的尼西部落用水果计数。

[12]English number words were probably object-specific as well,but their meanings have long been lost.The word “five” probably has something to do with “hand.” Eleven and 12 meant something akin to “one over” and “two over”—over a full count of 10 fingers.

[12]英语中的数词很可能也曾特指物体。不过,如今数词中的物体含义早已丧失。比如,five(5)一词很可能跟hand(手)有关。eleven(11)和twelve(12)则接近于“多1”和“多2”——十个手指都数完后,还多了“1”和“2”。

[13]The math Americans use today is a decimal,or base 10,system.We inherited it from the ancient Greeks.However,other cultures show a great deal of variety.Some ancient Chinese,as well as a tribe in South Africa,used a base 2 system.Base 3 is rare,but not unheard of among Native American tribes.

[13]美国人的数学系统使用十进制,也就是以10为基础的系统,这是从古希腊人那儿继承下来的。不过,以哪个数字为基数,在各个文化间差异很大。有些古代中国人,还有南非的某个部落,使用以数字2为基数的二进制。三进制很少见,但偶尔也会有人使用,例如某些美洲土著部落。

[14]The ancient Babylonians used a sexagesimal17sexagesimal六十的;六十进位的。,or base 60,system.Many vestiges18vestige遗迹,遗痕。of that system remain today.That’s why we have 60 minutes in an hour and 360 degrees in a circle.

[14]古巴比伦人用的则是六十进制,也就是以60为基数的系统。这种计数系统的影响一直遗留至今,所以60分钟才会等于1个小时、圆周才会有360度。

Written numbers

数字的书写

[15]What about written numbers?

[15]那么,数字如何书写呢?

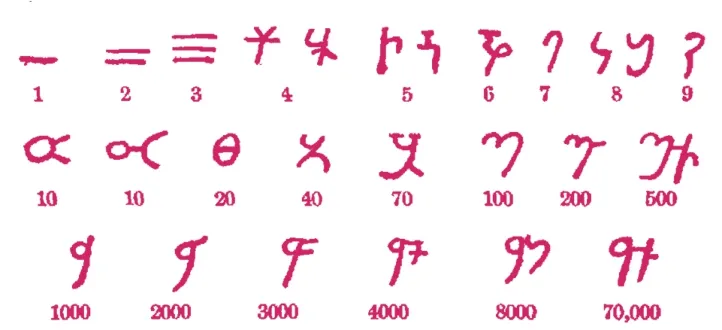

[16]Ancient Mesopotamia19古美索不达米亚,西南亚古文明,位于底格里斯河和幼发拉底河之间,现伊拉克境内。had a very simple numerical system.It used just two symbols: a vertical wedge (v)to represent 1 and a horizontal wedge (<)to represent 10.So <<vvv could represent 23.

[16]古美索不达米亚人的书面数字系统很简单,只有两个符号:竖的楔形(v)代表1,横的楔形(<)代表10。所以<<vvv就代表 23。

[17]But the Mesopotamians had no concept of zero either as a number or as a place holder.By way of analogy,it would be as if a modern person were unable to distinguish between 5.03,53 and 503.Context was essential.

[17]但是,美索不达米亚人没有“0”的概念。“0”既没有被列为数字,也不占位。打个比方,这就好像现代人没法区分5.03、53和503一样。没有“0”,数字前后的上下文就成了区分的关键。

[18]The ancient Egyptians used different hieroglyphs20hieroglyph象形文字。for each power21power乘方,幂。of 10.The number one was a vertical stroke,just as we currently use.But 10 was a heel bone,100 a scroll or coiled rope,1000 a lotus flower,10,000 a pointed finger,100,000 a tadpole and 1,000,000 the god Heh22赫神,古埃及神灵,是“无限”或“永恒”的人格化。holding up the universe.

[18]古埃及人用不同的象形文字表示10的幂。数字1就是直直的一竖,跟我们目前使用的数字差不多;不过,古埃及人的10却用踵骨来表示。100用一个卷轴或一盘绳子,1000用莲花,10000用伸出的手指,100000用蝌蚪,1000000则是赫神托起整个宇宙。

[19]The numerals most of us know today developed over time in India,where computation and algebra were of utmost importance.It was also here that many modern rules for multiplication,division,square roots and the like were first born.These ideas were further developed and gradually transmitted to the Western world via Islamic scholars.That’s why we now refer to our numerals as the Hindu-Arabic numeral system.

[19]大多数现代人熟知的数字系统起源并发展于古印度。在古印度,计算和代数这两门学问,占据最重要的地位。现代数学的很多规则,如乘、除、平方根之类,也诞生于古印度。后来,伊斯兰学者们进一步发展了古印度的数字系统和数学规则,并渐渐传播到西方世界。由此,我们的数字系统才得名“印度-阿拉伯数字系统”。

[20]It’s good for a young struggling math student to realize that it took thousands of years to progress from counting“one,two,many” to our modern mathematical world.■

[20]从1、2数到许多,再到我们今日的数学世界,其间经历了几千年的艰辛发展历程。知晓这段历史后,同样艰辛挣扎的数学专业年轻学子,一定会觉得安慰吧。□

(译者曾获第三届“《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛优秀奖)