在风景园林研究中定义“城市中的自然”

2018-11-19狄德瑞奇布鲁斯严妮张诗阳

著:(德)狄德瑞奇·布鲁斯 译:严妮 校:张诗阳

风景园林行业日渐广泛的社会作用需要学科产生新的知识[1]。学科也亟需进行深入的研究为其实践奠定坚实可靠的基础[2]。项目型工作,如那些在工作室里进行的或本科课程设计,与通过实验生成科学实证依据的学术研究和满足一般研究标准的其他类型研究有根本的不同。

为了了解实证研究在风景园林研究报告结果中所占的比例,Meijering等[3]系统地回顾了国际同行评审期刊上发表的与风景园林相关的研究论文。在抽样论文中,只有42%的论文有实证研究报告,同时仅有12%的报告提出了明确的研究问题。面对这些令人担忧的发现,亟需采取行动。

为了深化对风景园林研究特征和本质的理解,提高学者、专业人士、教师和学生等有关如何制定研究计划和完善研究方法方面的认知,Van den Brink等[4]出版了《风景园林研究的方法和方法论》一书。目前,研究者们正广泛地使用该书开展研究以及界定研究问题和方法。

下文是该书中部分章节的摘录(引号内为引用部分),并总结了各章节作者在未来研究中推荐使用的方法。其目的是提高对风景园林研究特殊属性的理解。Backhaus等[5]提出了应对城市水资源挑战的方案。为了创造缓解城市热岛效应的小气候,Brown和Gillespi[6]报告了关于城市环境热舒适度的研究。面对当前健康危机带来的挑战,特别是在西方世界,Ward Thompson[7]的报告对设计“健康景观”的必备知识进行了扩充。从遗产管理开始,瞬息万变的世界中各类挑战日趋加剧,Taylor[8]将其研究聚焦于景观的无形价值意义及其在风景园林设计中所扮演的角色。

1 研究示例—城市水体

世界人口中有一半以上居住在城市,并仍在持续增长。通过提供基于验证的设计专业知识,风景园林学科对综合应对全球城市水资源挑战做出了重要贡献。Backhaus等[5]介绍了3个解决水资源相关问题的风景园林专业研究。

3项研究都与城市水管理实践相关,被称作基于景观的雨洪管理(LSM)。LSM指的是“通过储蓄、渗透和蒸发来管理城市景观中的径流,从而促进自然水循环以改善局部小气候,补给地下水、提供灌溉用水等”。LSM的水管理方法包括一系列不同的措施,如“绿色屋顶,透水铺装,生物沼泽和水塘”。

3项研究涵盖了3种介于城市与场地之间不同的景观尺度。研究内容包括:1)20例已建成LSM项目的回顾性比较分析;2)回顾性分析了哥本哈根某建成区中,为改进LSM解决方案采取第一环路集水策略的设计过程;3)对设计过程实验及结果进行回顾性比较分析。

3项研究均使用了若干个不同的案例。第一项研究使用了20个案例并旨在了解已建成项目中LSM的最新技术概况。其余两项研究使用的案例较少,但侧重于深入分析。

实例和数据的采集方式如下:

·场地考察,个人观察,图像记录;

·查阅文献、地图和设计图纸;

·对设计过程进行录像、观察和记录;

·对工作坊和与最终使用者的协商会进行录像、个人观察和记录;

·对设计师和其他项目利益相关者进行半预设性访谈。

第一项研究通过采用5个关键参数对20个案例进行回顾性分析,确定了雨洪管理项目的具体特征,即可以优化或最小化项目的美学价值。第二项研究解释了如何在整个城市地下水系统的规模下,利用LSM技术来适应城市现有的排水系统。通过对整个城市地下水系统采用LSM技术,来了解风景园林研究如何适应现有城市排水系统。第三项研究是一个“设计实验”,旨在回答 “风景园林师在场地规模下的雨洪管理工作中遇到过哪些设计挑战?”。总而言之,通过回归实践,这3项研究有助于解决复杂性问题。在研究二和三中所展示的设计过程的具体特质得益于规划和设计所固有的解释学特性。

2 研究示例—城市气候

由于全球气候变化(GCC)和城市热岛效应(UHI),城市逐渐变成“不宜居的气候环境”。气候和热舒适度会影响人们的审美偏好。

气候变暖导致某些疾病传播,栖息地丧失导致野生动物濒临灭绝,而物种栖息地的关键组成部分就是小气候。与正常的夏季相比,高温期间需要消耗更多能量使城市中的建筑环境降温。

城市是大多数人生活中最常接触的景观。因此,努力缓解GCC和UHI效应以及研究城市环境热舒适度等变得非常重要。风景园林师无法控制宏观尺度气候,但可以改善中观尺度气候(如建成区比绿地更加温暖、干燥),同时通过景观改造以改善城市开放空间的小气候。

由于气候是由影响人们的物理因素组成的,因此需要对所有因素进行监测和记录,包括受景观中建筑物、植物和其他表面影响的温度、湿度、风和辐射。

同时,必须将记录的测量结果与人类在不同微气候条件下对热舒适度的感知记录相关联。因此,风景园林设计的热舒适度研究需要将自然科学和社会科学的方法结合起来。Brown和Gillespie[6]提出了室外环境热舒适模型,其中包括用于计算景观中能量流的方程式,景观中各元素对小气候的影响方式以及景观中能量流与热舒适度的关联模式。

研究者还提供了在热舒适度研究中理解人们观点的方法。实例和数据收集情况如下:

·检测小气候的组成部分,包括太阳和地面辐射、空气温度、湿度以及风等(各因素均通过专业仪器和技术确保测量的准确性);

·观察和记录人们在城市景观中的停留地点,并广泛比较各类型小气候条件;

·对城市开放空间使用者进行访谈,通过问卷调查评估人们对热舒适度(即热感觉)的感知。研究采用观测和社会调查并行的方法,对特定地点的小气候进行监测。

研究目标是根据特定地点的小气候条件找出受试者热感知与能量预算之间的关系。“这项典型的研究将人们设身于一系列小气候条件之下,并使研究参与者接触不同的热舒适度水平”。“设计驱动型研究”所取得的进展为小气候研究和实验提供了额外的机遇[9]。从迄今为止取得的研究成果来看,越来越多的实例表明城市气候影响着人类的健康和福祉。

3 研究示例—城市健康和福祉

了解如何设计保持身心健康、提供积极生活方式和健康心理的景观具有重大的社会意义[7]。正如研究城市水和气候问题一样,健康支撑型景观的研究范围极广,从国家、区域级风景园林规划到具体的城市、公园及花园设计。邻里或社区尺度的景观项目对景观和健康之间关联性研究有巨大的潜力。

为了理解“不同景观特征、人们与它们的接触方式与不同类型的健康行为、结果之间的关联”,Ward Thompson[7]提出了复合型方法并进行了大量案例研究,展示了如何使用不同方法来研究风景园林设计与健康、福祉之间的联系。

这些案例包括:1)在老龄化社会中支持户外活动的环境横向研究,包含调研活动、福祉和生活质量等方面,并将其与室外环境属性相关联;2)以住宅街道的实例,进行环境设计介入对幸福感影响的纵向研究;3)以联合分析为途径,了解不同环境要素的相对重要性。

实例与数据收集情况如下:

·通过邮寄或在线方式,开发和使用固定问卷;

·一段时间内,对部分参与者进行追踪调查,在(设计)干预环境变化前后采访同一批参与者;

·通过对环境变化前后的景观进行评估,对物理环境中各项变化的连续性记录,以及在环境变化前后对使用者行为进行观察,将受访者的访谈结果与其身体和行为变化进行关联;

·向受访者呈现具体对象或情境特征的综合体(综合体具备多种属性,同时每个属性具备多重价值),而后要求其在给定的集合中做出首要选择(选择通过比较多个属性中的不同值,并基于所有属性考虑后联合分析得出的实用程序而产生)。

这些案例说明了每种研究方法的优势、劣势和挑战,并提出了研究者在使用时需要考虑的细节问题。“其所描述的方法绝不是探求景观设计和人们健康、福祉之间联系的详尽说明”。还有更深入的研究方法以提供关于使用者如何对景观做出反应的详细说明,比如照片、语音采访和“追踪调研”的方式,长期研究更是如此。

“在社会科学和环境研究的背景下,横向比较调查可提供有价值的信息表明人们的特性、行为与环境之间的关系,但此法也有不可避免的缺点,即变量间的关联方向不能完全确定”。在关于健康、福祉和景观的研究中,明确方法的鲁棒性是很重要的。

鉴于健康、环境和个人之间复杂而动态的关系,很难明确人类健康与当地环境之间存在因果关系。同时需要指出,大多数研究,特别是涉及人类参与者的任何研究,都需要注意伦理标准和行为规范;大学和主要资助者通常需要获得伦理道德上的认可才能开展研究。

4 研究示例—景观的无形价值

景观向土地所有者、参观者和使用者展示了有关景观的无形价值—即“对社区最广泛的意义以及对挖掘遗产价值的作用”[8]。遗产与价值、意义和美均有着千丝万缕的联系。景观不仅仅被看作是物质要素和自然要素的集合,而是一种特征形成的过程。Taylor[8]提出了相关方法来考察研究者如何在实践中运用相应手段揭示景观意义和无形价值。研究者从“人类提出的价值源于何处,遗产来自哪里?”这个问题开始,研究提取文献中的案例以及澳大利亚新南威尔士州温哲卡利比郡的历史景观评估的案例。实例和数据收集情况如下:

·根据档案的主要和次要来源,历史资料以及对景观特征的现场检查和评估,确定景观类型及其设定;

·记录景观历史(例如使用景观传记法);

·评估包括文化价值和意识形态在内的景观特征(例如使用景观特征评估法);

·分析和评估景观,以了解景观中的美学、历史、科学、社会和精神文化内涵等内在价值。

研究者提出的方法成功回应了涉及具体景观时,如何认识、保护和管理文化遗产的无形价值。这种对文化遗产和遗产景观的研究方法,与关注于著名考古遗迹和建筑为重点的文化遗产精英鉴赏方法截然不同。对关联价值的鉴识能力为风景园林研究者和实践者提供了机会,从而对理解景观的无形价值和人类意义及价值积累过程的研究实践领域做出了独特贡献。在风景园林师参与应对遗产景观管理的实践中,关键之处在于所使用的研究方法而不仅仅是视觉评价。通过跨学科团队合作进行深入研究,将有助于指导研究方法的实施,以定义和构想其文化和历史背景。

5 以城市中的自然为对象的设计型风景园林研究

此研究通常有3个阶段[10]:1)制定研究计划;2)进行研究;3)汇报研究成果(例如发表论文或学术报告)。研究成果能够填补知识空白。明确知识空白之处是设计研究课题的开始。该过程的这一阶段包括:“概念型研究设计”和“技术型研究设计”。

1)“概念型研究设计”解决研究中“为什么”(WHY)和“是什么”(WHAT)的问题。找到研究问题的答案有助于填补知识空白。一个概念性的研究框架可以解释项目的原因和内容,其通常由相关的定义、理论和模型组成。

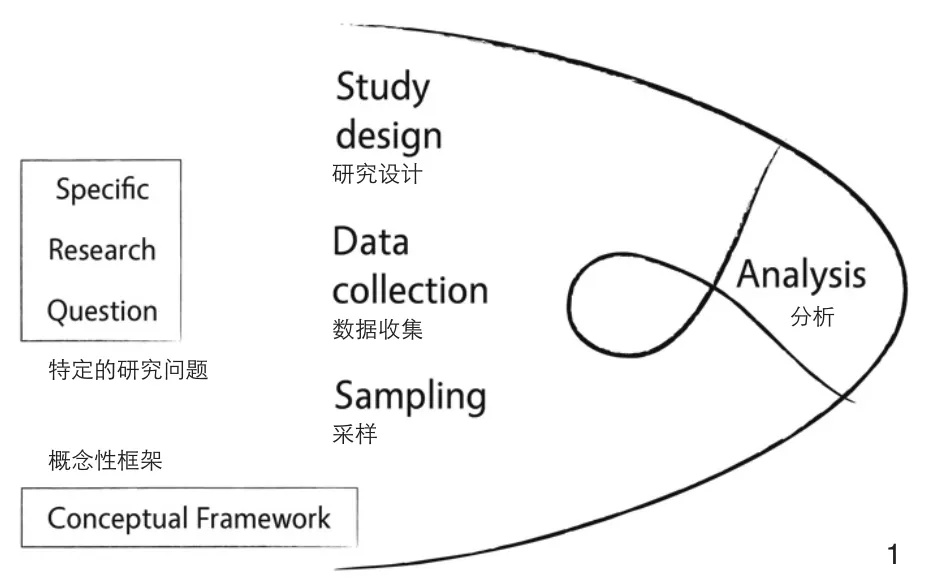

2)“技术型研究设计”解决“如何完成研究”(HOW)的问题。“如何”侧重于寻找研究问题的答案。研究者设计用于进行研究的途径或“策略”,例如收集数据的途径、采样策略、选择获取案例和数据单元的策略,以及案例和数据的分析策略(图1)。

出于实用目的,研究者将研究项目分成许多明确的子课题或“模块”。为每个模块赋予特定的方法,然后将所有模块获得的实例和数据综合在一起(图2)。为了构建模块,研究者可能首先制定一般性研究问题(GRQ),并将其分为2个或多个具体问题(SRQs),以便指导各个模块中的子研究。

1 技术型研究设计:针对一个特定的研究问题Technical research design: respondings to one Specific Research Question

2 综合体:针对于一般的设计问题Synthesis: responding to general Research Question(s)

例如,当研究者通常询问如何以最佳方式对城市区域进行设计,以便“提供热舒适环境,并最大限度地减少城市热岛的影响”时,Brown和Gillespie[6]建议定义2个具体的(相互关联的)问题。第一个问题是“景观中的建筑物、植物和其他表面如何改变温度、湿度、风和辐射?”第二个问题是“人类在不同的微气候条件下如何感知热舒适度”。每个具体研究问题对应一个“研究模块”,而获得的结果综合起来回答一般性研究问题。也可以在同一研究模块中对多个具体研究问题进行作答。

又例如,Backhaus等[5]通过现场观察与图像记录、半预设性访谈和文献分析相结合的方法来评估雨洪管理项目在施工数年后的“使用现状”。同样,Taylor[8]表示可以结合多种不同的方法探索遗产景观评估中的某个具体问题并获取答案。Ward Thompson[7]通过调查“活动、健康和生活质量数据”,并将其与“户外环境属性”相关联,以“复合型方法”对2个具体研究问题进行解答。这涉及到数个阶段,“从焦点问题开始,然后根据问卷进行更广泛的调查”。

如果根据研究与设计之间的关系来梳理上述情况和实例,我们将得到3组研究:“以设计为目的的研究”“基于设计的研究”和“设计驱动型研究”。“以设计为目的的研究”包括使用不同领域的方法进行研究;自然科学方法(例如气象学方法)、工程学方法(如测量地表径流)或社会科学方法(例如人员采访)提供支持设计决策的经验证据。“基于设计的研究”包括关于设计产品和成果的研究;研究者可能会使用人文学科(如历史研究法)、艺术学科(如文献研究法)以及其他领域的方法。在这两组的所有研究中,风景园林研究者从其他学科和领域借用方法。第三组是“设计驱动型研究”,该组研究主动将设计作为研究方法。

由于“设计驱动型研究”在风景园林研究中扮演着越来越重要的角色,因此风景园林设计过程自身逐渐成为重要的文化实践。“设计驱动型研究”包括所有主动以设计为方法的研究[9,11-12],其基本原则是设计者从研究某一问题开始,然后产生和评估应对这些问题的观点(图3)。继续针对特定问题开发原型解决方案,然后研究群体(包括设计人员)根据特定标准对这些解决方案进行测试。这时就会进行反复设计并重复测试空间布局。在某些阶段,特别是当需要选择若干备选解决方案之一用于进一步实施时,测试就可能包括对资金和技术可行性的评估,以及对水文、生物多样性和土地利用等方面的影响[13-14]。

在这个反复过程中,积极和反馈性的设计活动起基础性作用[10]。采用设计和科学、人文和其他领域研究方法的研究设计将包括设计过程和严格测试等几个不同阶段(图4)。设计和测试将由此以循环的方式产生新的知识。这种方法使严格测试和设计相辅相成,设计成为研究的固有部分[14]。Lenzholzer等[9]认为当设计符合学术研究的程序和价值观时,设计就是研究,并且他们为设计提出了标准的研究框架。“设计驱动型研究”将设计过程从专业人员的核心工作工具上升为研究方法,这是一种采用多种连续分析和反馈的方法,一种使问题解决过程易于理解,并在一定程度上可以为其他人效仿的方法[5]。

3 设计过程:针对特定的(设计)问题Design process: responding to specific (design) problems

4 通过设计及研究设计效果和过程以产生新的知识Generating knowledge through designing and studying design

通过以上案例可以发现,“设计驱动型研究”有2种类型。

1)研究设计效果:设计和施工过程并行,例如检验景观干预成果(在景观干预之前、期间和之后应用同一套方法);

2)研究设计过程,例如通过开发和反馈性地测试不同的设计方案(应用相同的方法和标准),包括:

·在过程中研究;

·对设计过程进行回顾性分析;

·在设计实验过程的比较分析。

6 结论

传统观念中自然与城市是截然对立的,同样研究与实践之间也是如此。另一方面,一些学者指出,城市和自然、研究和实践是相辅相成的,存在辩证关系[15-16]。如果将驱动过程以及空间、自然和人类层面共同考虑,研究者就可以成功地应对社会挑战。风景园林研究基于“设计思维”,设计必须依靠并反映该领域多样性的研究,最终通过实践和学术研究共同构建知识体系。

风景园林学者和从业者通过响应国家政府和国际组织指出的当务之急,为全世界的研究议程做出贡献[1]。通过研究城市和自然、研究和实践关系,相关学者和从业者正在做出重要的社会贡献,即制定未来风景园林发展和管理路线的指导方针[17],为传播和落实与风景园林和环境有关的政策提供知识。

未来风景园林的研究领域必须有助于推动风景园林学成为具有特定属性的独立知识领域,成为由其知识体系和独特研究方法来界定的一门学科[2]。对于风景园林师来说,将“自然与城市”并置思考十分重要:它对探索生态路径和工程解决方案,囊括艺术与哲学、人文学和美学方法有重要意义。另外,建议新增风景园林社会学家一职。景观与设计在实体化之前是存在于人们的思想中的,学者与从业者甚至可以在思想实验和增强现实中创造景观,而不是实地改造[18]。

The broadening of the role of landscape architecture in society calls for the discipline to generate new knowledge[1]. There is a desperate need for more research to equip the discipline with a solid evidential base for its practice[2]. Project related work,such as done in of fices and in undergraduate study programmes, is fundamentally different from the kind of academic research undertaken to generate evidence through empirical and other types of studies that meet general research standards.

With the aim to learn what percentage of landscape architecture research report findings from empirical studies, Meijering et al.[3]systematically reviewed papers that appeared in international peerreviewed journals that publish landscape architecture research. Of the sampled papers, a mere 42%reported on empirical research, and only 12% stated a definite research question. These findings are alarming. Action is needed.

With the aim to improve the understanding of the character and nature of landscape architecture research, and to raise awareness how to approach research design and methodological development among academics and professionals, teachers and students, van den Brink et al.[4]published the book“Research in Landscape Architecture. Methods and Methodology”. Researchers are now using this book widely for getting started in their studies and defining research questions and methods.

The following presents excerpts from some book chapters (quotation marks indicate quotes)and summarises which methods chapter-authors recommend to use in future research. The objective is to increase the understanding of the specific nature of landscape architecture research.Backhaus et al.[5]are offering solutions that help solving urban water challenges. In order to create microclimates that ameliorate the effects of urban heat island intensification Brown & Gillespie[6]report about researching thermally comfortable urban environments. Challenged by current health crises, particularly in the western world, Ward Thompson[7]reports on generating knowledge needed for designing “healthy landscapes”. Starting with heritage management, a growing challenge in a rapidly changing world, Taylor[8]speaks about research that puts the focus on intangible landscape meanings and values and on their role in landscape design.

1 Water in the city, research examples

More than half the world population lives in cities, and the number is increasing. By contributing evidence-based design expertise, landscape architecture makes important contributions to integrated responses to the global urban water challenge. Backhaus et al.[5]present three landscape architecture studies that are addressing water related research questions.

All of the three studies relate to the practise of managing urban water events that the authors call Landscape-based Stormwater Management (LSM).LSM refers to “managing runoff in the urban landscape through retention, in filtration and evapotranspiration,thus supporting a natural water cycle with a locally improved microclimate, groundwater recharge, water availability for vegetation, etc.” The LSM approach to water management comprises and uses a range of different “measures such as green roofs, porous pavement, bio-swales and ponds.”

The three studies cover three different landscape scales, starting with a citywide scale and ending with site-scale. The studies are 1) a retrospective comparative analysis of twenty built LSM projects, 2) a retrospective analysis of design processes for a first-loop catchment strategy for the retrofitting of LSM solutions in an existing built up area of Copenhagen and 3) a retrospective comparative analysis of experimental design processes and their outcomes.

Each of the three studies is working with a different number of cases. While the first study uses 20 cases and aims to get an overview of the state of the art of LSM in built projects, the two other studies are using fewer cases but focus on in-depth analysis. Evidence and data collection occurs by:

·Site visits, personal observations,photographic documentation;

·Review of literature, maps and design drawings;

·Video recordings, personal observations and note taking of design processes;

·Video recordings, personal observations and note taking of workshops and meetings with end-users;

·Semi-structured interviews with designers and project stakeholders.

Through the retrospective analysis of 20 cases and by using five key parameters, the first study identified specific characteristics of stormwater management projects that might optimise or minimise a project”s aesthetic quality. The second study generated knowledge on how to adapt existing urban drainage systems by use of LSM at the scale of entire sewer-sheds. The third study was a“design experiment” aimed to answer the research question: “Which design challenges do landscape architects meet, when working with landscape based stormwater management at site-scale?” Altogether,and by using real-world settings, the three studies contribute to addressing problem complexity.The specific characteristics of the design process presented in studies 2 and 3 greatly benefit from the hermeneutic qualities that are inherent to planning and designing.

2 Climate in the city, research examples

Due to global climate change (GCC) and urban heat island intensification (UHI), cities are gradually turning into “climatically inhospitable environments.” It takes an increased amount of energy to cool buildings in urban areas during heat waves compared to normal summer weather.

Cities are the very landscapes where most people are spending most of their lives. Hence,efforts to ameliorate effects of GCC and UHI and research about, among others, thermally comfortable urban environments are very important. We cannot control the macroclimate, but we can alter the mesoclimate (built-up areas tend to be warmer and drier than green areas) and we can definitely improve the microclimate of urban open space through landscape modification. Since climate is made up of physical factors that affect people, all factors need to be measured and recorded, including temperature,humidity, wind, and radiation that are modified by buildings, plants, and surfaces in the landscape.

At the same time, we must relate recorded measures to recordings of how humans perceive their thermal comfort under different microclimatic conditions. Therefore, research into designing landscapes for thermal comfort combines natural and social science methods. Brown & Gillespie[6]present outdoor thermal comfort models that include equations for calculating energy flows in the landscape, how elements in the landscape affect the microclimate and how energy flow in the landscape relate to thermal comfort.

The authors also present methods used for understanding peoples perceptions in thermal comfort studies. Evidence and data collection occur by:

·Measuring components of microclimate such as solar and terrestrial radiation, air temperature and humidity, and wind (each component has specialized instrumentation and techniques to ensure accurate and precise measurements);

·Observing and recording locations where people spend time in the urban landscape and compare a wide range of microclimatic conditions;

·Conducting interviews with people who use urban open space, using questionnaires to provide an estimate of people”s perceptions of their thermal comfort level (i.e. thermal sensation);

·Simultaneously and parallel to studies involving observational and social empirical methods, site-specific microclimate measurements are taken.

The goal is to find a relationship between the perceived thermal sensation of the subjects and the energy budget calculations based on site-specific microclimatic conditions. “A typical study would take people to a wide range of microclimatic conditions and expose study participants to a range of thermal comfort levels.”Advancements in “Research-through-Designing”provides additional opportunities for microclimate research involving experiments[9]. From study results obtained so far there now exists increasing evidence of the effects of urban climates on human health and well-being.

3 Health and well-being in the city,research examples

Understanding how we can design landscapes that support “health in mind and body, which support active lifestyles and mental wellbeing”,is of major societal interest[7]. As in research into urban water and climate issues, research into designing health-supporting landscapes ranges across a wide spectrum of scales, from national and regional landscape planning to the details of urban, park and garden design. The scale that offers great potential to see links between landscape and health is the neighbourhood or local community scale.

Seeking to understand “how different landscape characteristics, and peoples’ varying access to them, may be associated with different kinds of health behaviours and/or outcomes”,Ward Thompson[7]presents mixed-method approaches and a number of case studies that exemplify the use of different methods to research links between landscape design and health and wellbeing.

The examples are: 1) a cross-sectional research on environments that support outdoor access in an ageing society measuring aspects of activity,well-being and quality of life and relating these to outdoor environmental attributes; 2)longitudinal studies to explore well-being effects of environmental design interventions using examples of residential streets; 3) Conjoint Analysis as an approach to learn about the comparative importance of different environmental elements.Evidence and data collection occurs by:

·Developing and applying fixed-response questionnaires, by mailing or online;

·Following a cohort of participants over periods of time, interviewing the same people before and after (designed) environmental change interventions;

·Relating results obtained from interviewing people to physical and to behavioural changes,by undertaking landscape audits before and after environmental change interventions and ensuring to record physical environments consistently and to note any changes to these environments,and by undertaking behaviour observations of use in environments before and after change interventions;

·Presenting respondents to a conjoint with profile characteristics of objects or situations,which consist of several attributes, and varying values for each attribute, and asking them to choose which is preferred within a given set (Choice is made by comparing different values in multiple attributes and the utilities generated in conjoint analysis are based on relative considerations of all attributes).

The examples illustrate each research methods” strengths, weaknesses and challenges and identify the detailed issues that researchers need to take into account in considering the use of each. “The methods described are by no means an exhaustive illustration of what might be used to explore links between landscape design and people’s health and well-being.” More in-depth approaches exist that can provide detailed insights on how people respond to the landscape such as Photo-Voice-Interviews and “go-along” methods especially if conducted over long periods.

“While cross-sectional surveys may be used in contexts of social science and environmental research, and provide useful indications of important associations between aspects of people’s characteristics and behaviour in relation to aspects of their environment, they have an unavoidable shortcoming. It is never possible to be completely confident about the direction of any association between one variable and another.” In the context of research into health, well-being and landscape, it is important to be explicit about the robustness of the method.

Given the complex and dynamic relationship between health, environment and individual, the level of proof possible to demonstrate a causal relationship between people’s health and their local environment may be difficult to ascertain. It is also important to note that most research, and particularly any research involving human participants, requires attention to ethical standards and procedures; universities and major funders will normally require ethics approval before a study is allowed to proceed.

4 Intangible landscape values, research examples

Landscapes demonstrate associative intangible values related to the meaning of a landscape for the landowners and for visitors and users—that is“for the community in its widest sense and their engagement with an active use of the heritage”[8].Heritage is inextricably linked to the emergence of the ideas of values and meanings, and of beauty.Landscape is not simply what is seen as an assembly of physical components and natural elements, but rather a process by which identities are formed.Taylor[8]presents approaches to examine the way in which researcher employ methods used in practice to unravel landscape meaning and intangible values.The author starts with the question of “whose values are we addressing and whose heritage is it?” The studies presented are examples from the literature and the example of the Historic Landscape Assessment of Wingecarribee Shire,New South Wales, Australia. Evidence and data collection occurs by:

·Identifying types of landscapes and their setting, based on archival primary and secondary sources, historical information and onsite examination and assessment of the landscape character;

·Documenting landscape history (e.g. by using Landscape Biography approaches);

·Assessing landscape characteristics including cultural values and ideologies (e.g. by using Landscape Character Assessment approaches);

·Analysing and evaluating landscapes to understand inherent values such as aesthetic, historic,scientific, social and spiritual or cultural significance.

Methods presented by the author respond to the challenge of recognising, protecting and managing intangible values of cultural heritage with specific reference to landscapes. This approach to cultural heritage and heritage landscape in particular, marks a divergence from the elite connoisseurship approach to cultural heritage focusing on famous archaeological remains and buildings. Appreciation of associative values presents an opportunity for a landscape architecture researcher to make a distinctive contribution to the field of study and practice of understanding intangible aspects of landscape and to the process of how human meanings and values accumulate.In practice where landscape architects are involved in dealing with heritage landscape management,it is critical that a study method used reaches beyond being merely a visual appraisal. Thorough research through interdisciplinary teamwork will be instrumental in guiding the conduct of the method to address the idea of defining cultural and historic contexts.

5 Designing landscape architecture research for studying nature in the city

Research is a process that usually has three stages[10]: 1) designing the research project, 2) doing the research and 3) reporting on findings (e.g.publishing a paper or a report). Research findings represent a knowledge-gain that fills a knowledgegap. Identifying a knowledge-gap is the starting point for designing the research project. This stage of the process consists of the “conceptual research design”, and the “technical research design”.

1) The conceptual research design addresses the WHY and the WHAT of the research. Finding answers to RQs helps filling knowledge gaps. A conceptual framework informs both the WHY and the WHAT of the research project; the conceptual framework consists of relevant definitions, theories and models.

2) The technical research design addresses HOW-the-research-will-be-done. The HOW focuses on finding answers to RQs. Researchers design the tools, or “instruments”, for doing the research, e.g. tools by which one collects data, the sampling strategy, the strategy by which one selects the units from which evidence and data will be obtained, and the strategy for evidence and data analysis (Fig. 1).

For practical purposes, researchers will divide their research project into a number of well-defined sub-studies, or “modules”. They will equip each module with specific methods, and later synthesize evidence and data obtained through all of the modules together (Fig. 2). To frame modules,researchers might first formulate a General Research Question (GRQ) and divide it into two or more Specific Research Questions (SRQs) that then guide sub-studies in individual modules.

For example, when researchers are generally asking how to best design urban areas so that “they will provide thermally comfortable environments and minimise the impact of urban heat islands”,Brown & Gillespie[6]suggest defining two specific(interrelated) questions. The first question is “How are temperature, humidity, wind, and radiation modified by buildings, plants, and surfaces in the landscape?” The second question is “How do humans perceive their thermal comfort under different microclimatic conditions?” Each SRQ corresponds to one “research module”, and results obtained will be synthesized to respond to the GRQ.It may also be possible to respond to more SRQs in one research module.

For example, Backhaus et al.[5]combined methods of site observation with photographic documentation, semi-structured interviews and document analysis to find answers to the one specific question of how stormwater management projects are “performing” several years after being constructed. Similarly, Taylor[8]suggests combining a number of different methods to find answers to the one specific challenge of heritage landscape assessment. Ward Thompson[7], by measuring“aspects of activity, wellbeing and quality of life” and relating these to “outdoor environmental attributes”is responding to two SRQs by a “mixed methods approach”. This involves several phases, “starting with focus groups and then a wider survey based on a questionnaire”.

If we organise the cases and examples above according to relationships between research and design, we find three groups: “Research-for-Design”, “Research-on-Design”, and “Researchthrough-Designing”. Research-for-Design includes studies using methods from different fields;natural science methods (e.g. from meteorology),engineering methods (e.g. measuring surface water runoff) or social sciences methods (e.g.interviewing people) provide empirical evidence that support design decisions. Research-on-Design includes studies about the products and outcomes of design; researchers may be using methods from the humanities (e.g. from history) and the arts(e.g. from literature studies) and other fields. In all studies belonging to these two groups, landscape architecture researcher borrow methods from disciplines and fields outside of their own. The third group is Research-through-Designing (RtD)and this group includes studies that actively employ designing as a research method.

As RtD plays an increasingly important role in landscape architecture research, the process of designing landscapes itself is becoming an important cultural practice. RtD includes all research and studies that actively employ designing as a research method[9,11-12]. The basic principles of RtD are that designers start by 1) studying a problem and 2) generating and assessing ideas that respond to these problems (Fig. 3). They continue by 3) developing prototype solutions to particular problems and then 4) groups of people(including designers) test these solutions against certain criteria. An iterative process is now on its way of designing and repeatedly testing spatial configurations. At certain stages, particularly when one of several alternative solutions must be selected for further implementation, testing may include assessing solutions for financial and technical feasibility, and for impact on e.g.hydrology, biodiversity and land use[13-14].

In the iterative process, the active and reflective activity of designing plays a fundamental role[10]. A study design that employs methods of designing and of sciences, humanities, and other fields, would include several discrete phases of designing and rigorous testing (Fig. 4).Designing and testing will thus help generating new knowledge in a cyclic fashion. This approach,in which rigorous testing and designing are acknowledging and supporting each other,designing is an inherent part of doing research[14].Lenzholzer et al.[9]suggest that designing is research when it complies with the procedures and values of academic research, and they suggest a framework of research criteria for designing. RtD elevates the design process from being the central working tool of a practitioner to becoming a research approach,one that employs several methods of continuous analysis and reflection, and one that makes the process of problem solving comprehensible and,to some degree, repeatable for others[5].

In the cases and examples above, we find two types of RtD:

·Studying design effects parallel to processes of designing and implementing design decisions,e.g. by auditing landscape change interventions(applying the same set of methods before, during and after change interventions);

·Studying design processes, e.g. by developing and reflectively testing different design solutions(applying the same set methods and criteria) either:

·during the process (experimental or realworld), or;

·as retrospective analysis of design processes, or;

·as comparative analysis of experimental design processes.

6 Conclusion

A conventional assumption about nature and city is that they represent a dichotomy. Another conventional assumption is that research and practice represent a dichotomy. On the other hand, some authors have pointed out that city/nature and research/practice relationships take a number of mutually beneficial forms, particularly dialectical ones[15-16].We can address societal challenges successfully if we consider driving processes and the spatial, natural and human dimensions altogether. Landscape architecture relies on “design thinking” and, in turn, designing must rely upon research that reflects the diversity of the field,building the body of knowledge through practice and academic research together.

By contributing to research agendas worldwide,landscape architecture academics and practitioners will influence and respond to priorities set by national governments and international organisations[1].By studying city/nature and research/practice relationships, landscape architecture researchers and practitioners are making important societal contributions. They are devising guidelines for the future course of landscape development and management[17]. They are providing knowledge for informing and implementing policy pertaining to landscape and the environment.

The scope of future landscape architecture research must contribute to the promotion of landscape architecture as a discipline, and as a discrete field of knowledge with a specific identity,defined by its own body of knowledge and its own research methods[2]. For landscape architects it is important to think “Nature and City” together:to explore ecological pathways and engineering solutions, to include art and philosophy, to include the humanities and to take aesthetic approaches.In addition, I suggest adding the position of a landscape architecture sociologist. Landscape exists within people’s thoughts, including designs,before they materialise physically. We can even make landscapes, as in thought experiments and augmented realities, without changing them physically[18].

Notes:

① This is a speech delivered by the author at the International Landscape Architecture Symposium in 2017.

② The copyrights of all figures are with the author. The author thanks Franziska Bernstein for technical assistance in producing these drawings. Fig.3 was based on references [5], [12], [13].

(Editor / WANG Yilan)

注释:

① 本文为作者在2017世界风景园林师高峰讲坛上的发言稿。

② 所有图片版权归作者所有。感谢Franziska Bernstein对图纸绘制的技术支持。图3根据参考文献[5]、[12]、[13]绘制。

(编辑/王一兰)