古迹重绘

——“德意志”视角下的彩饰之辩:希托夫、森佩尔、库格勒与他们这一代 (下)

2017-12-25荷雅丽李路珂AlexandraHarrerLILuke

荷雅丽,李路珂 /Alexandra Harrer, LI Luke

蒋雨彤 译,李路珂 校 / Translated by JIANG Yutong; Revised by LI Luke

古迹重绘

——“德意志”视角下的彩饰之辩:希托夫、森佩尔、库格勒与他们这一代 (下)

荷雅丽,李路珂 /Alexandra Harrer, LI Luke

蒋雨彤 译,李路珂 校 / Translated by JIANG Yutong; Revised by LI Luke

19世纪的一场关于建筑彩饰的论争颠覆了我们对于古典建筑,特别是古希腊和古罗马神庙建筑的认知。作为建筑理论领域较为后起的一支力量,“德意志”在这一过程中扮演了特殊的角色。本文详细回顾了这场论争的来龙去脉,各派学说如何卷入其中,又如何在特定的社会机制下推动着事实的逐步揭示,最终达到观念的彻底改变。这一事件直接地影响到现代希腊复兴建筑,甚至也波及到西方的中国建筑史编纂学。

19世纪欧洲彩饰之辩,古代希腊建筑,建筑色彩,阿法雅神庙,帕提农神庙,伊格纳茨·希托夫,戈特弗里德·森佩尔,弗朗兹·库格勒,约翰·约阿希姆·温克尔曼,詹姆斯·弗格森

(上篇请参见世界建筑,201709期,p104)

3.1.5 库格勒,一次柔化色调的折中尝试(在森佩尔/希托夫和劳尔–罗谢特之间)

次年(1835),一个来自德国的声音回应了森佩尔对于无条件接受古典建筑采用彩饰的要求,弗朗兹·特奥多尔·库格勒(1808–1858)以一种温和而折中的方式阐释了彩饰理论:根据考特梅尔关于希腊彩饰的观点,他提交了一个对于帕提农神庙彩饰的复原设计(《关于希腊建筑和雕塑的彩饰及其局限性》,1835),这一成果在几年后被森佩尔在《建筑四要素》中给予了回应[1]5。

库格勒是19世纪德意志在艺术史与诗歌领域的一位主要的权威人物,同时也是普鲁士王国的文化部长。他编纂了第一部关于绘画史和艺术史的全球性调查报告(《绘画史手册,从康斯坦丁大帝到现在》,1837;《艺术史手册》,1842),还有一本非常流行的书《腓特烈大帝的一生》(莱比锡,1840)21)。然而在史学编纂领域,他的光芒往往被他最出色的学生兼搭档雅各布·布尔卡特(1818–1897)所掩盖——后者是一位瑞士艺术史家,被誉为“文艺复兴历史的伟大探索者”。

库格勒试图在这场彩饰之辩中扮演调停人的角色。他的论文《关于希腊建筑和雕塑的彩饰及其局限性》尝试在中立的态度下对论争双方的观点进行讨论,从而在支持派与反对派之间寻求一种平衡[8]4。然而,值得注意的是,他将论文标题中特意强调了希腊的建筑和雕塑的“局限性”,表明他认为希腊建筑对于色彩的运用实际上是局限于特定条件和特定地域的。

在这场论辩中,库格勒并不是任何一方的热情支持者。一方面,他承认考特梅尔的成果以及彩绘在雕塑上的使用,但另一方面他对彩饰在历史建筑上的普遍性持宽容而非完全接受的态度,认为古典文献上的相关证据缺乏重要性[8]114。库格勒观点的核心在于,古典建筑上的色彩运用应该与材料保持一致,而在洁白的大理石上施以彩饰,是既不必要也不恰当的。因此,他拒绝接受希托夫与森佩尔提出的,建筑与建筑构件上普遍存在彩饰这一观点[8]819。他激烈地抨击了希托夫太过艳丽的色彩组合,强调这种做法只适用于个别情况,而不能一概而论。库格勒强调了彩饰法对于建筑所在地理环境的依赖性,并拒绝接受阿提卡——以雅典城为核心的阿提卡半岛,古希腊的历史中心——存在建筑彩饰的观点[8]10。此外,他将彩饰的运用限定于早期的建筑之中。概括起来,库格勒提出了以下几点:第一,色彩服从形式;第二,一旦某个时期的人们能够彻底地驾驭“形式”,色彩就变得无关紧要;第三,只有当形式(在美学层面)不够有力的前提下,色彩才能作为补充。库格勒没有评价罗谢特富有争议的木板彩绘观点。

3.1.6 勒托,从文献学角度对希托夫的支持

让·安东尼·勒托(1787–1848)是一位法国文献学家,同时也是法兰西公学院的教授(1831年任历史学讲席教授,1838–1848年任考古学讲席教授),1840年成为国家档案的监管人。勒托最重要的著作是《埃及的希腊与拉丁铭文集》(两卷本,1842,1848)[3]116。

与此前在这场彩饰之辩中支持派与反对派动辄冗长繁缛的学术探讨不同,作为希托夫最好的朋友之一,勒托在1835年以16封写给希托夫的优美信件表达了他的支持。在《一个艺术品商人写给一个艺术家的信:关于古希腊和古罗马的神庙及其他公共或私人建筑装饰上使用墙面彩绘》(1835)中,勒托生动地描绘了一幅详实而包罗万象的古代艺术生活图景。他引经据典地反对了罗谢特的理论。勒托彬彬有礼却极尽讽刺之能事,逐字逐句地讨论了罗谢特的观点,向世人展示这位素以学识渊博自居的考古学家却在自己的领域犯了大量的错误。对于古典文献的细致研究表明,在希腊本土和意大利(殖民地)一样,墙面彩绘和木板彩绘都是关键的设计元素。此外,勒托区分了不同的绘画方法,并逐个详细讨论。他的讨论使得希托夫的理论更加广为人知,并表明了后者是经得起科学和文献学检验的。

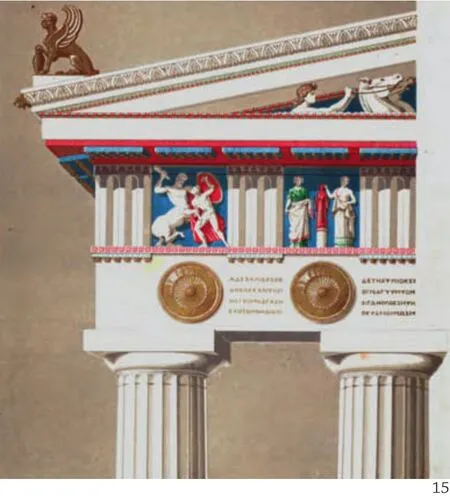

15 帕提农神庙东立面,库格勒的复原图(库格勒,《关于希腊建筑和雕塑的彩饰及其局限性》,图版1)/East facade of the Parthenon, reconstructed by Kugler (Kugler,Über die Polychromie der griechischen Architektur, plate 1)

(See World Architecture 201709, p104 for part one)

3.1.5 Kugler, an attempt at mediation, to soften the tone (between Semper/Hittorff and Raoul-Rochette)

A response to Semper's unconditional demand for the acknowledgment of painted decoration in antiquity came from Germany the following year (1835), when Franz Theodor Kugler (1808 –1858) put forward his moderate, conciliatory interpretation of the polychromy theory: following Quatremère de Quincy's ideas of Greek polychromy,he presented a reconstruction of the polychrome decoration of the Parthenon (Über die Polychromie der griechischen Architektur und Skulptur und ihre Grenzen; 1835), which was answered several years later by Semper's Vier Elemente der Baukunst.[1]5

Kugler was one of the leading 19th-century German authorities in art history and poetry and the cultural administrator for the Prussian state.He also compiled the first global survey text of the history of painting (Handbuch der Geschichte der Malerei von Constantin dem Grossen bis auf die neuere Zeit, 1837) and the history of art (Handbuch der Kunstgeschichte, 1842), as well as his immensely popular Geschichte Friedrichs des Grossen (Leipzig,1840).21)And yet, in modern historiography,his achievements are often eclipsed by his most prominent student and collaborator – the Swiss art historian and "great discoverer of the age of the Renaissance" – Jacob Burckhardt (1818 – 1997).

Kugler wanted to play the role of mediator in the polychromy debate: Über die Polychromie was intended to strike a balance between supporters and opponents by providing an impartial discussion of the arguments of both sides.[8]4However, it is significant that he gave his work the title "…Greek architecture and sculpture and its limitations"(…Architektur und Skulptur und ihre Grenzen),indicating that the use of colors in Greek architecture was restricted (by conditions) and confined (to a given area).

Kugler did not feel passionately about the subject either way. He acknowledged the work of Quatremère de Quincy and the use of colors on sculpture, but he condoned rather than wholeheartedly accepted the universality of polychromy in historical architecture, attaching little significance to the testimonies of classical texts.[8]114The core of Kugler's argument was that colors were used in antiquity in accordance with the materials used, and the coloring of white marble was unnecessary and inappropriate. As a consequence,he rejected the idea of a universality of polychrome buildings and building parts in the sense intended by Hittorff and Semper.[8]8-9He harshly criticized Hittorff for his too-colorful color scheme, arguing that it could not be applied generally, but only to specific cases. Kugler stressed the dependency between polychromy and the geographic location of buildings, rejecting the idea of the use of polychromy for Attica, the historical heartland of ancient Greece located on the Attic peninsula and centered on the city of Athens.[8]10Moreover, he restricted polychromy to the architecture of older periods. In essence, Kugler argued that: first, color follows form;second, as soon as a period has mastered "form","color" becomes unnecessary; and third, color is used as a supplement to form only if form proves insufficient (in aesthetic expression). He did not comment on Raoul-Rochette's controversial views on wooden panel painting.

3.1.6 Letronne, support for Hittorff from a philologist

Jean Antoine Letronne (1787 – 1848) was a French philologist and professor at the Collège de France (chair of history, 1831; chair of archaeology,1838-1848) and in 1840 he became keeper of the national archives. Letronne's most important work is his Recueil des inscriptions grecques et latines de l'Égypte (2 vols, 1842 and 1848).[3]116

Letronne, one of Hittorff's closest friends,demonstrated his support in 1835 in the pleasing form of sixteen letters addressed to Hittorf,avoiding the lengthy and cumbersome scholarly discussion of previous supporters and opponents in the polychromy debate. His Lettres d'un antiquaire à un artiste sur l'emploi de la peinture historique murale dans la décoration des temples et des autres édifices publics et particuliers chez les Grecs et les Romains (1835) gave an extensive and informative picture of the artistic life of the ancients. He disproved Raoul-Rochette's theory with the aid of classical quotations. Politely, but using irony to the full, he went through Raoul-Rochette's arguments point by point, and showed that the pretentious archeological scholar had made substantive errors in his own discipline. Detailed study of classical texts revealed that in Greece as well as in Italy,both wall painting and wood panel painting had been key design elements. In addition, Letronne distinguished between different painting methods and discussed them in detail. His argument publicly acknowledged Hittorff's theory and showed that it stood up to scientific and philological examination.

3.2 Further development and end of debate

Raoul-Rochette was not out of the debate, but his scholarly vanity had been deeply wounded –simply by the fact that someone had contradicted him.[3]119For example, in 1836-1837, he struck back,criticizing Semper for his ideas of "elaboration of form with color" and "not staying truthful to the(building) material", by obscuring the beauty of the material by covering it with a colored coating.22)In this final stage of discussion, the debate was fueled by increasingly rapid statements by its key players,who exchanged opinions on the subject in a harsh,often personally insulting manner (Raoul-Rochette against Letronne and Hittorff; Letronne against Raoul-Rochette and Kugler).23)The polychromy debate gradually degenerated into a conf l ict between philology (Letronne) and archaeology (Rochette),and both sides called upon judges to arbitrate the dispute to resolve the disagreement. As a consequence, the Académie had to make a stand and voice a carefully-formulated explanation – not least because by then, young French architects were allowed to study polychrome architecture in Italy or Greece (as pensionnaires at the French Academy in Rome or the French School in Athens): for example,in 1845 Alexis Paccard (1813 – 1867) reconstructed the Parthenon, and in 1846 Philippe Auguste Titeux(1812 – 1846) the Propylaea. Their observations in Greece proper largely confirmed the findings of Hittorff in the Greek colonies in Italy, although their visual recoveries were sometimes rather more fiction than fact.[3]122-123

3.2 进一步的发展与论战的终结

罗谢特并没有退出这场争辩,但是他作为一个学者的自尊心被深深地伤害了——仅仅因为有人站在了他的对立面[3]119。比方说,在1836–1837年,他回击了森佩尔,指责他“用色彩表达形式”的观点“未能坚持(建筑)材料的真实性原则”,因为色彩涂层完全掩盖了材料的美感22)。这场争辩到了最后一幕,已经愈演愈烈,变为主角之间日趋紧锣密鼓的声明、回应,甚至人身攻击(罗谢特对阵勒托与希托夫;勒托对阵罗谢特与库格勒)23)。论争后来逐渐缩小为文献学(勒托)与考古学(罗谢特)的对峙,双方均提出请求仲裁方来解决这场争议。接下来,学院不得不表明立场,并发表了一份措辞谨慎的声明——尤其是因为那个时候,年轻的法国建筑师们已经被允许在意大利和希腊研究建筑彩饰(作为罗马大奖的获得者,在罗马法兰西学院或者雅典法兰西考古学院学习)。例如,1845年亚历克西斯·皮卡德(1813–1867)复原了帕提农神庙;1846年菲利普·奥古斯特·蒂特(1812–1846)复原了卫城山门。尽管他们的复原设计大多是虚构大于实际,但他们的在希腊的观察极大地证实了希托夫在意大利希腊殖民区的发现[3]122-123。

最重要的是,在这个阶段,考古学证据日益丰富,甚至引起了伦敦大英博物馆馆藏埃尔金石雕的化学分析24)。在这些证据面前,争论内容的实质发生了转换。就如库格勒的折中方案所显示的那样,争论的重点变为了探讨建筑彩饰的外延和内涵,而非古典建筑的彩饰本身是否存在,因为那时这已经成为一个不争的事实。

1851年,希托夫终于出版了自1830年起就受到期待的,配有大量插图的赛林努特的恩培多克勒神庙的完整复原设计,尽管这次依然有反对的声音(库格勒)。然而,这场纷争中的关键人物都相继与世长辞,而反对派的人数也在逐年减少——勒托、罗谢特、库格勒、希托夫和森佩尔分别在1848年、1854年、1858年、1867年和1879年辞世。这场彩饰之辩前后持续了30多年,直到此时才逐渐归于尾声,留给我们一个令人震惊又无可辩驳的事实——古希腊神庙终于亮出它富有色彩的一面。

4 结论

与古典建筑有关的彩饰问题,使德籍或德裔建筑学者们(希托夫、森佩尔和库格勒)在国际舞台上收获了更大的存在感,但也在很长一段时间内禁锢了法、德两国的专业学者在艺术与建筑史、考古学以及文献学范畴的学术交流。同时,尽管雅典卫城和古典希腊建筑一直都是现代学者所关注的中心,但由于一些历史原因,“研究彩饰法的这一代先驱者们没有关注帕提农神庙(森佩尔和库格勒除外),而是截取了一些零星证据,用以支持自己的理论。”[4]270——位于埃伊纳小岛上的阿法雅神庙就是这样的一个证据,因此具有了某种重要性。

无论如何,对这座无名古建筑的发现和视觉复原,拉开了这场广泛的跨文化交流的序幕,而这场发生于19世纪的彩饰之辩,彻底改变了今日我们看待古典建筑的方式。

作为总结,我们现在可以回答文章开头所提的3个问题——即事件的历史梗概、取得的新知,以及彩饰之辩的世界性意义:

4.1 “彩饰之辩”的历史梗概

这场学术论争起源于人们不得不直面一个出人意料且从观念上难以接受的现象,而后在不断被揭示的事实依据面前,开始逐渐接受并习以为常。从彩饰法之辩开始(19世纪的第二个10年),直到1830年代中期,古典希腊艺术及建筑存在彩饰的可能性,在学者与普通大众之中引发了激烈的争论,而这更加凸显了辩题的重要性。而后,鉴于有大量确凿证据证明希腊神庙上存在着使用颜色的痕迹,这场争论的重点逐步转移到探讨彩饰的外延(时代与地域范围)、内涵和色彩特性(饱和度、基色、与采光的关系等)。

4.2 “彩饰之辩”的背后

在这里我们可以看到200年前学会的运作机制——实际上现在还是这样运作的:通过书信、考古发掘报告、普及性小册子以及带有大量插图的专著,进行着学术观点的精彩交锋以及激烈的口水战。

此外,这场纷争一部分是在巴黎美术学院这个国家(政治)平台上进行的。巴黎美术学院是19世纪前期法国建筑学理论的诞生地,而在学校核心人物和学生的参与下,这些理论也极大地影响了国际化的现代设计学。彩饰之辩也体现了十九世纪初期巴黎美术学院的内部斗争和学生反叛——对于这个“在某种程度上偶然而随意的”建筑彩饰问题的流行,德国建筑理论家汉诺-沃尔特·克鲁夫特进行了如下解读:年轻的浪漫主义者们将这个原本属于考古学和古物研究的话题当成了“武器”,用以对抗考特梅尔领导的巴黎美术学院所固守的温克尔曼式古典主义教条25)。

通过这场西方彩饰之辩,我们还可以深刻地领会到19世纪欧洲的思想状况(思考问题的方式),以及法兰西与德意志学者的思维模式(态度及看法)。在彩饰这个概念最初进入人们视野的时候,它是不被接受的,因为其概念动摇了西方建筑理论的根基,而这个根基是建立在文艺复兴时期(“单色调的高贵”、镶嵌着古典元素的平坦表面所体现的灰白而平面化的古典主义、伯鲁乃列斯基、阿尔伯蒂)和新古典主义时期(形式统领色彩、形式作为图解温克尔曼美学概念“高贵的单纯与静谧的伟大”的工具)对古典建筑的随意解读之上的26)。

也就是说,直到19世纪,随着现代考古学正式成为一门学科,新的发掘和勘察不断动摇着罗马建筑至高无上的地位,并强调希腊建筑的重要性(“希腊-罗马之争”),对于古典建筑的想象被放到了特定信仰、判断和环境的背景之下。在不可能证实这些构想的情况下(由于无法到达真正的遗址现场,以及实物证据的缺乏),人们得出的往往是与事实相去甚远的曲解,这是需要克服的一大挑战。因此,历经多年,(古典建筑中的)彩饰才得到广泛的接受。

值得特别注意的是,不论是支持派还是反对派,积极参与这场彩饰之辩的学者们都是各自领域的专家,在各自的职位上取得了卓越而富有开创性的成就。比如库格勒创造了“加洛林风格”(他是第一个用此术语的人),这在艺术史领域已获公认。尽管希托夫、罗谢特、森佩尔、库格勒以及勒托等学者的重要性在西方世界早已被公认,在中文文献中关于他们的叙述却很贫乏,仅是粗略地扫过各个领域,并只关注他们学术生涯中某一特定阶段的研究。

此外,这场论争还体现出某些人性的特点——“人非圣贤,孰能无过”,而且人生并不是非黑即白,而是有很多灰色地带的。也就是说,虽然以今天的我们所掌握的知识来判断,当时某些学者——例如罗谢特和库格勒——选择了“错误的”立场,但这并不能削弱他们在当时的声望和地位,也不会影响他们的职业发展。库格勒在年仅28岁时就毫不费力地写出了《关于希腊建筑和雕塑的彩饰及其局限性》(1835),试图对彩饰法这一热点议题起到调停作用。但这篇文章实际上暴露了他的某种“本色”,表现了他对于这个问题的消极和怀疑。大约10年后(1840),库格勒就被吸收进入学术评议会,并被委派到文化部任职,负责监管普鲁士的各类艺术。此外,他的作品还为他获得了国际上的知名度:他的绘画史研究报告被翻译成了英文(1842),且多次修订出版,和詹姆斯·弗格森(1808–1886)的代表作《各国建筑通史:从远古到现代》(1860–1870)一同,树立了世界艺术史研究的样板,并在英语地区非常流行。弗格森的引入,对于本文开端所提出的第三个问题而言尤为有趣。

Most importantly, at this stage, faced with growing archaeological evidence that even led to a chemical testing of the Elgin marbles in the British Museum in London, there was a shift in the content of the debate. Instead of asking whether or not polychromy existed in antiquity, since this had already become an established fact that no one could afford to refute – the shift was towards asking about the extent and nature of the polychromy in architecture, as exemplified by Kugler's proposed compromise solution.

In 1851, Hittorff finally published the complete,lavishly-illustrated edition of the reconstructed Empedocles Temple in Selinunte, which had been awaiting completion since 1830, albeit again not without opposition (Kugler). However, the key players in the conflict were gradually dying off, and the number of opponents shrank from year to year –Letronne passed away in 1848, Raoul-Rochette in 1854, Kugler in 1858, Hittorff in 1867, and Semper in 1879. The polychromy debate had been carried on for more than three decades, and only then did it slowly come to an end, leaving us with the astonishing and undeniable fact that ancient Greek temples had finally shown their colors.

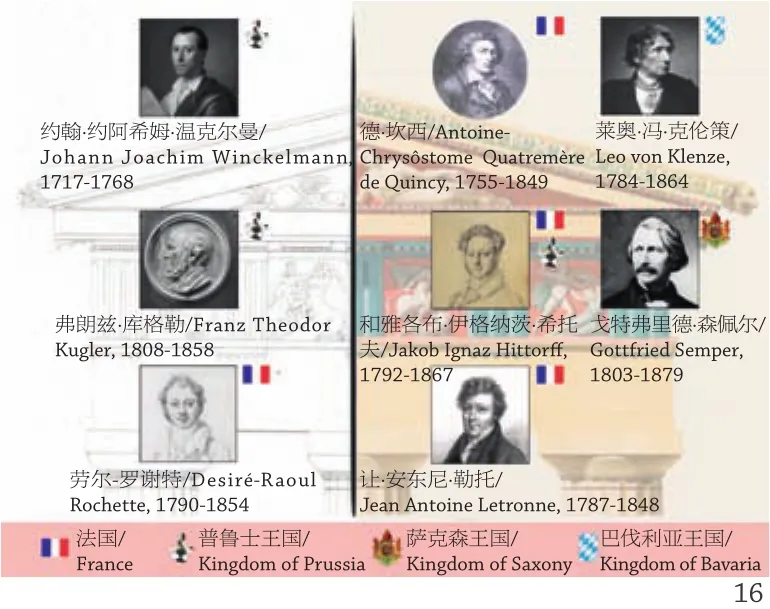

16 法–德彩饰之辩中的关键人物(绘制:荷雅丽)/Key players in the German-French polychrome debate (Drawing:Alexandra Harrer)

4 Conclusions

The subject of polychromy in connection with the historical architecture of antiquity established a greater presence of German/German-born architectural scholars on the international stage(Hittorff, Semper, and Kugler), but for a long time"poisoned" academic relations between the French and the German authorities on art and architectural history, archaeology, and philology. And although the acropolis in Athens and the classical architecture of Greece itself have long been the centre of modern scholarly attention, for historical reasons,"the generation of the pioneers of the polychromy question did not focus on the Parthenon (with the exception of Semper [and Kugler]) but used much more scattered evidence to more personal ends"[4]270– the Aphaia Temple on the small island of Aegina was one of them and herein lies some of its importance.

In any case, the discovery and visual recovery of this historically rather insignificant building set the scene for a broad cross-cultural dialogue that revolutionized the way we see antiquity today –the 19th century polychromy issue. To draw a final conclusion, we may now answer the questions posed at the beginning regarding the historical course of events, knowledge gained, and the global significance of the polychromy debate.

4.1 Changes in the course of the polychromy debate

What happened back then was at first a confrontation with the unexpected and virtually unbelievable phenomenon, followed by its gradual habituation (acceptance upon repeated exposure to factual evidence). At the beginning of the polychromy debate (1810s) until the mid-1830s,the mere possibility of colorful classical Greek art and architecture provoked a serious debate among scholars and the general public, which highlights the importance of the question. Then, given the mass of overwhelmingly convincing evidence of traces of color on Hellenistic temples, the debate shifted its focus increasingly in the direction of the extent of the polychromy (time period; geographic region)and the nature and quality of the colors that had been applied (bright or dull; basic color; dependency on light exposure).

4.2 Behind the scene of the polychromy debate

What we can see here is the mechanism of how academia worked two hundred years ago – and in fact still works today: an exciting back and forth of scholarly opinions and a battle of words, expressed in letters, excavation reports, pamphlets, and lavishly-illustrated print publications.

And what is more, the debate was partly fought on the national (political) stage of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, the birthplace of early 19th-century French theory that had considerable inf l uence on modern international design, with its dignitaries and its students became involved. The dispute embodied an internal conflict and student revolt at the Académie des Beaux-Arts in the early 19th century: the German architectural theorist Hanno-Walter Kruft explains the popularity of the "somewhat incidental and arbitrary issue"of architectural polychromy, originally an archaeological and antiquarian issue, which the young Romantics used as "a weapon" to attack the rigid classical norms of the Winckelmann tradition still upheld at the Académie by Quatremère.25)

4.3 “彩饰之辩”与全球建筑史:19世纪的德意志——希腊古典复兴与中国建筑史的书写

关于第三个问题,“德意志”视角下的彩饰之辩对于我们今天理解全球建筑史至关重要。通过这场争辩,我们能够窥探德国–希腊之间的紧密联系,以及其现实意义。不光德籍或德裔学者及建筑师在这场理论争辩中起到带头作用,会说德语的,以及有德意志教育背景的建筑师们还积极地促成了彩饰在当代建筑上的视觉重现27)。

正是在希腊独立战争之后的雅典,德国建筑师冯·加特纳 (1791–1847)为希腊的奥托一世大帝(约1832–1862)设计了旧皇宫(1836–1843,现为希腊议会大厦)——奥托大帝是巴伐利亚路德维希一世大帝(1786–1868)的儿子,而路德维希一世大帝就是10年前哈勒尔的赞助人,也是正是他下令在慕尼黑古代雕塑博物馆对阿法雅神庙进行复原。在雅典,还有丹麦裔奥地利建筑师特奥费尔·翰森(1813–1891)设计了雅典大学(1859–1885)、扎皮翁宫(1874–1888)以及希腊国家图书馆(1887–1902),在翰森离开希腊之后,这些建筑都是在他的代理人,德裔希腊建筑师恩斯特·齐勒尔(1837–1923)的监理下建成的。这些位于雅典的德意志–希腊复兴建筑的柱头和线脚使用了“具有生动异域风情的金棕榈叶装饰,并在重点部位点缀了红色、绿色和蓝色”。[4]260光洁的白色柱子立在深红色墙面的前方,展现出一种稳健而雅致的古希腊彩饰风味。

17 雅典的后希腊式(希腊复兴式)建筑:雅典大学正立面细部(左,摄影:李路珂)与扎皮翁宫的内庭院(右),均由特奥费尔·翰森设计(图片来源:www.commons.wikipedia.org)/Neo-Grec architecture in Athens, Academy of Athens (left, photo by LI Luke) and the courtyard of the Zappeion (right, public domain work, www.commons.wikipedia.org), both designed by Theophil Hansen.

此外,出人意料的是,发生于欧洲中部的彩饰之辩对于万里之外的中国,竟十分有助于理解本国建筑的史学观念,以及建筑史的书写。1876年,弗格森出版了名为《印度及东方建筑史》的四卷本著作,在这本书里他以贬抑的语调评论中国的建筑传统:

“……中国建筑并不值得太多关注。然而有一点,中国是现今唯一还将彩饰作为建筑的重要组成部分的民族,所以中国建筑还是有一定启发性的:实际上对于他们而言,色彩比形式重要得多;且目前的效果是比较令人愉悦而满意的。这是因为,在艺术的较低阶段,情况无疑总是这样的。但是,对于较高阶段的艺术而言,毋庸置疑,尽管色彩是最有价值的附加之物,它并不像形式那样具有直指人心的崇高表现力。”

弗格森认为在中国建筑中,色彩是凌驾于形式之上的,是建筑美的决定性因素,这一挑衅式的论断源于他自己对中国建筑的误解——他拒绝承认中国建筑结构中比例的作用,以及根据社会等级和礼制意义而调整的颜色等级体系。

虽然弗格森不得不承认古希腊神庙中建筑彩饰的运用(“希腊人在他们的神庙内外施以彩绘”),但在他看来,中国建筑中刻板而千篇一律的色彩组合(既不表达建筑结构,也不适合特定地域条件)必须被视为一种缺乏教养、尚不成熟的表征。更有甚者,弗格森针对西方建筑提出了一套彩饰依赖于特定气候和地理条件的理论,所以只有在地中海的强烈阳光下,建筑彩饰才是可以允许的(“除了希腊与埃及这样的国家,仅仅通过在建筑外表面涂绘的方式来运用色彩,这一做法必然是错误的”)。然而,若已了解弗格森的语境背后这场刚刚平息不久的西方彩饰之辩,他的这种认知就如同这场辩论本身一样,是可以被理解和解释的。□

注释

20)克鲁夫特指出森佩尔抨击了克伦策对历史风格的模仿(《建筑理论史》,p311)。

21)他的《绘画史手册,从康斯坦丁大帝到现在》与《腓特烈大帝的一生》都有英译版(《绘画史手册》,伦敦,1842年,1911年以前出版了多个英文修订版;《腓特烈大帝的一生》,伦敦,1844,及其后的数个修订版)。库格勒唯一没有被翻译的书是《艺术史手册》,但此书的附图合集在1880年代于纽约出版了英文版本。

22)罗谢特的数篇论文发表在1836–1837年间的学者报上。

23)劳尔–罗谢特,《学者报》1836–1837年之间的一些文章;《未出版的古典绘画》,1836;《考古学信件》,1840。勒托,《一个古董商人写给一个艺术家的信之附录》,1837。关于人身攻击,参见范·赞特恩,《建筑彩饰法》,论文部分,p35。

24)埃尔金石雕指的是曾位于帕提农神庙、雅典卫城山门和伊瑞克提翁庙的古希腊雕塑。这些雕塑被埃尔金伯爵七世托马斯·布鲁斯(1766–1841)在1801–1802年间从神庙中移走,并带回大英帝国。

25)克鲁夫特,《建筑理论史》,第312页。范·赞特恩,建筑彩饰法,p11。范·赞特恩进一步解释道,对于很多年轻的法国建筑师(雅典法兰西学院罗马大奖获得者)来说,建筑彩饰法不是“循规蹈矩且一成不变的,而仅仅是(直接而多变的)涂鸦艺术的延续和实物的附属品。”(《帕提农神庙的彩饰》,p271)

26)森佩尔曾辛辣地指出所谓“单色调的高贵”纯粹是由伯鲁乃列斯基和米开朗基罗开创的,这种做法导致了“现代燕尾服和古董的杂糅”(《初评》,p16)。他主张“认为古典建筑是单色调是野蛮的”(同上,p20),以此抨击同时代的古典主义观点。

27)比如希腊建筑师帕纳伊斯·克罗斯(1818–1875)就被奥托大帝授予了奖学金并留学慕尼黑。

What we can also gain from the Western polychromy debate is a deep insight into the mentality (a particular way of thinking) of 19thcentury Europe and the mind-set of German and French scholars (their attitude or set of opinions).On its first appearance, the concept of polychromy was deemed to be unacceptable, a concept that undermined the very foundations of Western architectural theory rooted in the free interpretation of antiquity during the Renaissance ("novelty of monochromy"; grey-and-white planar classicism through flat surfaces veneered in classical elements;Brunelleschi, Alberti) and the neo-classicist period(superiority of form over color/form as shaping tool expressed in the aesthetic ideal of "noble simplicity and quiet grandeur"; Winckelmann).26)

That is to say, until the 19th century, which saw the establishment of modern archaeology as an academic discipline, when new discoveries and excavations challenged the primary role of Roman architecture and highlighted the importance of Greece ("Greco-Roman Controversy"), the architecture of antiquity was conceived in the light of individual beliefs, judgments, and circumstances.Without the possibility of verification (due to the inaccessibility of actual ruins and paucity of factual evidence), this had led to a distorted picture of the actual situation that posed quite a challenge to overcome. Consequently, it took many years for polychromy to gain widespread acceptance.

It is noteworthy that the scholars actively engaged in the polychromy debate were all experts in their relevant fields and proved their outstanding and pioneering achievements whatever position they took. Kugler, for example, had coined the concept of "Carolingian style" (being the first to use the term"Carolingian" ), which is taken for granted in the field of art history. Although the significance of scholars such as Hittorff, Raoul-Rochette, Semper,Kugler, and Letronne has long been recognized in the West, Chinese literature on the subject is sparse,spread out across disciplines and focused on studies of particular phases of their career.

Furthermore, there is a human side to this –to err is human, and moreover, life is not just black and white, but many shades in between. That is to say, taking the "wrong" side of the debate in the light of today's knowledge neither diminished the standing of scholars such as Raoul-Rochette and Kugler, who both enjoyed great popularity among their contemporaries, nor did it impair their career development. Kugler, who was 28 when he wrote his half-hearted attempt to mediate in the heated question of polychromy (Über die Polychromie,1835), which in fact rather showed his "true colors"(his reluctance and doubts on this matter), was called to the academic senate and appointed to the Ministry of Culture overseeing all the arts of Prussia just a decade later (1840s). Moreover, his work gained him international recognition: his survey text of painting history was translated into English (1842) and published in many revised editions, together with James Fergusson's (1808 –1886) standard work A History of Architecture in all Countries from the Earliest Times to the Present Day (1860 – 1870s) establishing as a genre the global art history survey text popular in the Englishreading world. The relation to Fergusson is especially interesting with regard to the last question posed at the beginning.

4.3 Global significance of the polychromy debate: 19th-century "German" Greek revival architecture and Chinese architectural historiography

The polychromy discussion seen through"German" eyes is significant for our modern understanding of global architectural history.Through the debate, we can unfold the close German-Greek relationship and its practical implications.Not only did German and German – born scholararchitects play a leading role in the course of the theoretical debate, but German – speaking and German – trained architects were also actively engaged in the visual recovery of polychromy in contemporary architecture.27)

It was in Athens, after the Greek War of Independence, that the German architect Friedrich von Gärtner (1791 – 1847) designed the Old Royal Palace(1836 – 1843; now the Hellenic Parliament) for King Otto of Greece (r. 1832 – 1862) – King Otto was the son of King Ludwig I of Bavaria (1786-1868), who was a patron of Haller's and who had commissioned the reconstruction of the Aphaia Temple in the Glyptothek in Munich a decade earlier – and the Danish-born Austrian architect Theophil Hansen (1813 – 1891)designed the Academy of Athens (1859 – 1885), the Zappeion (1874 – 1888), and the National Library of Greece (1887 – 1902), all of which were supervised by the German-born Greek architect Ernst Ziller(1837 – 1923), Hansen's representative when he was away. The German Greek revival architecture in Athens displays capitals and moldings "exotically enlivened with gold palmettes and touches of red,blue and green" and plain white columns standing in front of deep red walls, and presents a conservative and tasteful interpretation of ancient Greek polychromy.[4]260

Furthermore, it might come as a surprise to learn the central-European polychromy discussion is particularly useful for understanding the architectural history and historiography of a country far away from the center of the debate – China. In 1876, Fergusson published a 4th volume entitled The History of Indian and Eastern Architecture,in which he remarked disparagingly on Chinese building traditions:

"… it may be that Chinese architecture is not worthy of much attention. In one respect, however,it is instructive, since the Chinese are the only people who now employ polychromy as an essential part of their architecture: indeed, with them, color is far more essential than form; and certainly the result is so far pleasing and satisfactory, that for the lower grades of art it is hardly doubtful that it should always be so. For the higher grades, however,it is hardly less certain that color, though most valuable as an accessory, is incapable of that lofty power of expression which form conveys to the human mind."[9]688

Fergusson's provocative statement about the Chinese emphasizing color over form as a defining factor for architectural beauty was born of a misconception on his part, denying Chinese construction the effects of proportion and flexible color grading according to social rank and ritual significance.

[1] 范·赞特恩. 1830年代的建筑彩饰法. 纽约:加兰出版社,1977.

[2] 温岑茨·布里克曼和安德烈亚斯·舒尔 编. 色彩里的神——古典雕塑的彩饰. 慕尼黑:希尔默出版社,2010.

[3] 卡尔·哈默,雅各布·伊格纳茨·希托夫,1792–1867. 斯图加特:安东·希尔泽曼出版社,1968.

[4] 戴维·范·赞特恩,“帕提农神庙的彩饰”// 帕提农神庙及其对现代的影响. 帕纳约蒂斯·图尼基沃蒂斯编. 雅典:梅丽莎出版社. 1994.

[5] 汉诺-沃尔特·克鲁夫特. 建筑理论史:从维特鲁威到现在. 罗纳德·泰勒英译. 纽约:普林斯顿建筑出版社,1996. 王贵祥译. 北京:中国建筑工业出版社,2005.

[6] 富特文勒,《埃伊纳:阿法雅圣地》.

[7] 海因茨·奎特兹克,戈特弗里德·森佩尔的美学观点. 柏林:学术出版社,1962.

[8] 弗朗兹·库格勒. 关于希腊建筑和雕塑的彩饰及其局限性. 柏林. 1835.

[9] 詹姆斯·弗格森. 印度及东方建筑史. 建筑历史第1版第4卷. 伦敦. 1876. 赫尔施修订第3版第3卷. 伦敦.1899.

[10] 詹姆斯·弗格森(1808–1886),各国建筑通史:从远古到现代. 伦敦. 1865-1867. 赫尔施修订第3版第1卷. 伦敦. 1893.

参考书目

1. 罗伯特·亚当(1728–1792), 达尔马提亚斯帕拉托的戴克里先大帝皇宫遗址. 伦敦. 1764.

2. 查尔斯–路易斯·克莱里索(1721–1820),法兰西古迹之一:尼姆的遗迹. 巴黎. 1778.

3. 查尔斯·罗伯特·科尔雷尔(1788–1863),科尔雷尔,《埃伊纳的主神朱庇特庙与位于阿卡迪亚地区的费加里亚附近的巴塞的阿波罗·伊壁鸠鲁神庙》.伦敦. 1860.

4. 加布里埃尔·皮埃尔·马丁·迪蒙(1720–1791), 帕埃斯图姆,即普林尼所提及的帕埃斯图姆市1750年现存的3座古代神庙的平面图、剖面图、轮廓线图、立面几何分析及透视图。由J·G·苏夫洛测绘并绘制……于1750年. 巴黎. 1764.

5. 雅各布·伊格纳茨·希托夫(1792–1867),赛林努特的恩培多克勒神庙复原及希腊古建筑彩饰. 巴黎.1851.

6. 希腊的彩饰建筑——赛林努特卫城的恩培多克勒神庙的完整复原. 考古研究所年度通讯第2卷,1830:p263-284. 重刊. 美术学会刊第1卷,1830–31:p188-55.

7. 西西里的现代建筑——西西里主要城市中最优美的宗教建筑和最出众的公共或私人建筑集锦. 18期连载. 巴黎. 1826-1835.

8. 西西里的古代建筑——西西里主要城市和遗址中最值得探究的古迹集锦. 8期连载. 巴黎. 1827–1830.

9. 莱奥·冯·克伦策,阿格里真托的奥林匹亚宙斯神庙. 斯图加特. 1821. 1827修订版.

10. 绘画史手册 :从康斯坦丁大帝到现在. 柏林.1837;英译本. 伦敦. 1842

11. 艺术史手册. 斯图加特. 1842.

12. 腓特烈大帝的一生. 莱比锡,1840. 英译本. 伦敦.1844.

13. 让·安东尼·勒托(1787–1848),埃及的希腊与拉丁铭文集:基于亚历山大大帝到阿拉伯时期的国家政治史、行政管理和民事宗教机构的关联性研究.两卷本. 巴黎. 1842. 1848.

14. 一个艺术品商人写给一个艺术家的信:关于古希腊和古罗马的神庙及其他公共或私人建筑装饰上使用墙面彩绘. 巴黎. 1835.

15. 一个艺术品商人写给一个艺术家的信之附录:关于在神庙及其他公共或私人建筑装饰上使用墙面彩绘. 巴黎. 1837.

16. 乔瓦尼·巴蒂斯塔·皮拉内西(1720–1778). 建筑与透视图集第一卷,威尼斯建筑师皮拉内西绘制并雕版. 罗马. 1743.

17. 古代与现代罗马的景象集. 罗马. 1745.

18. 安东尼–克里索斯托姆·考特梅尔·德·坎西(1755–1849). 奥林匹亚的朱庇特:重新审视古代雕塑艺术. 巴黎. 1815.

19. 建筑学词典. 两卷本. 巴黎. 1789. 1832.

20. 劳尔–罗谢特(1790–1854), 古代壁画. 学者报.1833年6月. p361–371 .

21. 未出版的古希腊、伊特鲁里亚和古罗马的人物雕塑:1826-1827年间在意大利和西西里收集. 两卷本.巴黎. 1828. 1833.

22. 未出版的古代绘画,基于对希腊人和罗马人在圣殿或宗教建筑的装饰上运用彩绘的研究,及未出版的古代建筑. 巴黎. 1836.

23. 关于希腊绘画的考古学信件.巴黎. 1840.

24. 戈特弗里德·森佩尔(1803–1879), 关于古代彩饰建筑与雕塑的初评. 阿尔托纳. 1834.

25. 建筑与雕塑中色彩的运用. 柏林. 1834–1836.

26. 建筑四元素. 不伦瑞克. 1851.

27. 论文集. 柏林和斯图加特. 1884.

28. 詹姆斯·斯图尔特(1713–1788)和尼古拉斯·雷维特 (1721–1804),雅典的古迹. 四卷本. 伦敦.1762,1787,1784,1816.

29. 约翰·约阿希姆·温克尔曼(1717–1768), 关于在绘画与雕塑中模仿希腊艺术作品的思考. 德累斯顿/莱比锡. 1755.

30. 古代艺术史. 德累斯顿. 1764. 第二版. 1776.

31. 迈克·埃斯帕涅,本尼迪克特·萨伏伊和席琳·特劳特曼-沃勒,弗朗兹·西奥多·库格勒:一位德国艺术史学家和柏林诗人. 柏林:学术出版社. 2010.

32. 基利安·埃克,艺术对于人生的重要性:弗朗兹·库格勒与第一个艺术史教育机构. 马尔堡美学年鉴第32期. 2005:p7-15.

33. 亨里克·卡格,19世纪德国艺术史学的前瞻性:弗朗兹·库格勒,卡尔·施纳泽和戈特弗里德·森佩尔.艺术史学刊第9期. 2013:p1-26.

34. 唐纳德·戴维·施耐德, 雅各布·伊格纳茨·希托夫(1792–1867)的作品和理论. 两卷本. 纽约:加兰出版社,1977.

35. 雷内·施耐德,考特梅尔·德·坎西与他的艺术成就(1780–1830). 巴黎. 1910.

36. 渥瑞夫·锐查斯美术馆, 雅各布·伊格纳茨·希托夫,一位来自科隆的19世纪巴黎建筑师. 科隆:洛切尔出版社,1987.

To Fergusson, who by then had no choice but to acknowledge the polychromy of ancient Greek temples ("the Greeks painted their temples both internally and externally")[10], the rigid undifferentiated color scheme of Chinese buildings(neither necessarily serving to explain or give expression to the construction, nor being adaptive to specific local circumstances) must have seemed a sign of a lack of sophistication, lack of refinement.This is not least the case because for Western architecture, Fergusson established a dependency of colors from the specific climatic and geographic conditions of a place, allowing polychromy only for Mediterranean regions with bright light ("except in such countries as Egypt and Greece, it must always be a mistake to apply color by merely painting the surface of the building externally").[10]And yet, if seen in context, as a backdrop to the only recentlyresolved polychrome debate in the West, it is at least explainable and understandable as that debate was. □

Notes

21) His Handbuch der Geschichte der Malerei was translated into English (Handbook of the History of Painting, London 1842, and many revised English editions to 1911), and also his Geschichte Friedrichs des Grossen (Life of Frederick the Great,London, 1844 and subsequent English editions). The accompanying atlas of illustrations to his Handbuch der Kunstgeschichte, the only work not translated, was published in English in New York in the 1880s.

22) Several papers published in Journal des Savants,1836 – 37.

23) Raoul-Rochette, several articles in Journal des Savants 1836-37; Peintures antiques inédites, 1836;Lettres archéologiques, 1840. Letronne, Appendice aux lettres d'un antiquaire à un artiste, 1837. For the personal attacks see Van Zanten, The Architectural Polychromy, thesis, 35.

24) The Elgin marbles refers to the classical Greek sculptures removed from the Parthenon, the Propylaea,and the Erechtheum at the Athens Acropolis by Thomas Bruce (1766 – 1841), the 7th Earl of Elgin,between 1801 and 1812 and brought back to Great Britain.

25) Kruft, A History of Architectural Theory, 278. Van Zanten, The Architectural Polychromy, 11. Van Zanten further explains that for many young French architects(pensionnaires at the École française d'Athènes [French School at Athens]) polychromy was not "rule-bound and fixed, but merely the extension of graffiti [i.e.immediate and changing] and the attachment of actual objects." ("The painted decoration of the Parthenon,"271.)

26) Semper once poignantly pointed to the "novelty of monochromy" that only began with Brunelleschi and Michelangelo, leading to "hybrid creations born of modern tail-coats and Antiquity." (Vorläufige Bemerkungen, 16). Attacking contemporary Classicism, he perceived it as "barbaric that the monuments should have become monochrome."("Die Monumente sind durch Barbarei monochrom geworden" [Ibid., 20]).

27) The Greek architect Panagis Kalkos (1818-75) for example, received a scholarship by King Otto to study in Munich.

[1] van Zanten, David. The Architectural Polychromy of the 1830's. New York: Garland, 1977.

[2] Brinkmann, Vinzenz and Andreas Scholl (Eds).Bunte Götter. Die Farbigkeit antiker Skulptur. Munich:Hirmer, 2010.

[3] Hammer, Karl. Jakob Ignaz Hittorff. Ein Pariser Baumeister, 1792 – 1867. Stuttgart: Anton Hiersemann, 1968.

[4] van Zanten, David. "The painted decoration of the Parthenon". In The Parthenon and its Impact in Modern Times, edited by Panayotis Tournikiotis.Athens: Melissa Press, 1994.

[5] Kruft, Hanno-Walter. A History of Architectural Theory: From Vitruvius to the Present. Translated by Ronald Taylor. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996. Translated by Wang Guixiang. Beijing:Zhongguo jianzhu gongye chubanshe, 2005.

[6] Furtwängler, Adolf (1853 – 1907) et al. Aegina: Das Heiligtum der Aphaia. Academy of Sciences: Munich,1906.

[7] Quitzsch, Heinz. Die ästhetischen Anschauungen Gottfried Sempers. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1962.

[8] Kugler, Franz. Über die Polychromie der griechischen Architektur und Skulptur und ihre Grenzen. Berlin: 1835.

[9] Fergusson James. History of Indian and Eastern Architecture. 1st ed. Vol. 4 of A History of Architecture.London: 1876. Here, rev. 3rd ed. Vol. 3. London: 1899.

[10] Fergusson, James (1808 – 1886). A History of Architecture in all Countries from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. London: 1865 – 1867. Here, rev. 3rd ed. Vol. 1. London: 1893.

Bibliography

1. Adam, Robert (1728 – 1792). Ruins of the Palace of the Emperor Diocletian at Spalatro in Dalmatia.London: 1764.

2. Clérisseau, Charles-Louis (1721 – 1820). Antiquités de la France, prèmiere partie: monumens de Nismes.Paris: 1778.

3. Cockerell, Charles Robert (1788 – 1863). The Temples of Jupiter Panhellenius at Aegina and of Apollo Epicurus Bassae near Phigalaia in Arcadia.London: 1860.

4. Dumont, Gabriel-Pierre-Martin (1720 – 1791).Suite de plans, coupes, profils, élévations géométrales et perspectives de trois temples antiques, tels qu'ils existaient en 1750 dans la bourgade de Poesto, qui est la ville Poestum de Pline [...] ils ont été mesurés et dessinés par J.-G. Soufflot [...] en 1750. Paris: 1764.

5. Hittorff, Jakob Ignaz (1792 – 1867). Restitution du temple d'Empédocle à Sélinonte, ou l'architecture polychrôme chez les Grecs. Paris: 1851.

6. Hittorff, Jakob Ignaz (1792 – 1867). De l' architecture polychrôme chez les Grecs. "Annali dell' instituto di correspondenza archeologica 2 (1830): 263-84.Republished ("De l'architecture polychrôme chez les Grecs et restitution complète du temple d'Empédocle dans l'acropole de Sélinonte") in Journal de la Société Libre des Beaux-Arts 1 (1830 – 1831): 188-55.

7. Hittorff, Jakob Ignaz (1792 – 1867). Architecture moderne de la Sicile, ou recueil des plus beaux monuments religieux et des édifices publics et particuliers les plus remarquables des principales villes de la Sicile. 18 instalments. Paris: 1826 – 1835.

8. Hittorff, Jakob Ignaz (1792 – 1867). Architecture antique de la Sicile, ou recueil des plus intéressants monu- ments d'architecture des villes et des lieux les plus remarquables de la Sicile. 8 instalments. Paris:1827 – 1830.

9. von Klenze, Leo. Der Tempel des Olympsischen Jupiter von Agrigent. Stuttgart: 1821, revised 1827.

10. Kugler, Franz (1808 – 1858). Handbuch der Geschichte der Malerei von Constantin dem Grossen bis auf die neuere Zeit. Berlin: 1837. Translated into English,Handbook of the History of Painting. London: 1842.

11. Kugler, Franz (1808 – 1858). Handbuch der Kunstgeschichte. Stuttgart: 1842.

12. Kugler, Franz (1808 – 1858). Geschichte Friedrichs des Grossen. Leipzig, 1840. Translated into English,Life of Frederick the Great. London: 1844.

13. Letronne, Jean Antoine (1787 – 1848). Recueil des inscriptions grecques et latines de l'Égypte,étudiées dans leur rapport avec l'histoire politique,l'administration intérieure, les institutions civiles et réligieuses de ce pays depuis la conquête d'Alexandre jusqu'à celle des Arabes. 2 vols. Paris: 1842 and 1848.

14. Letronne, Jean Antoine (1787 – 1848). Lettres d'un antiquaire à un artiste sur l'emploi de la peinture historique murale dans la décoration des temples et des autres édifices publics et particuliers chez les Grecs et les Romains. Paris: 1835.

15. Letronne, Jean Antoine (1787 – 1848). Appendice aux lettres d'un antiquaire à un artiste sur l'emploi de la peinture historique murale dans la décoration des temples et des autres édifices publics ou particuliers.Paris: 1837.

16. Piranesi, Giovanni Battista (1720 – 1778). Prima parte di architetture e prospettive inventate ed incise da Giovanni Batta Piranesi architetto veneziano. Rome:1743.

17. Piranesi, Giovanni Battista (1720 – 1778). Varie vedute di Roma antica e moderna. Rome: 1745.

18. Quatremère de Quincy, Antoine – Chrysôstome(1755 – 1849). Le Jupiter olympien: l'art de la sculpture antique considéré sous un nouveau point de vue. Paris: 1815.

19. Quatremère de Quincy, Antoine – Chrysôstome(1755 – 1849). Dictionnaire historique de l'architecture. 2 vols. Paris: 1789 and 1832.

20. Rochette, Desiré-Raoul (1790 – 1854). "De la peinture sur mur chez les anciens." Journal des Savants(June 1833): 361 – 71.

21. Rochette, Desiré-Raoul (1790 – 1854). Monuments inédits d'antiquité figurée grecque, étrusque et romaine, recueillis pendant un voyage en Italie et en Sicile, dans les années 1826 et 1827. 2 vol. Paris: 1828,1833.

22. Rochette, Desiré-Raoul (1790 – 1854). Peintures antiques inédites précédées de recherches sur l'emploi de la peintures dans la décoration des édifices sacrés et publics chez les Grecs et les Romains, faisant suite aux monuments inédits. Paris: 1836.

23. Rochette, Desiré-Raoul (1790 – 1854). Lettres archéologiques sur la peinture des Grecs. Paris: 1840.

24. Semper, Gottfried (1803 – 1879). Vorläufige Bemerkungen über bemalte Architektur und Plastik bei den Alten. Altona: 1834.

25. Semper, Gottfried (1803 – 1879). Die Anwendung der Farben in der Architektur und Plastik. Berlin: 1834 –1836.

26. Semper, Gottfried (1803 – 1879). Vier Element der Baukunst. Braunschweig: 1851.

27. Semper, Gottfried (1803 – 1879). Kleine Schriften.Berlin und Stuttgart: 1884.

28. Stuart, James (1713 – 1788) and Nicholas Revett(1721 – 1804). Antiquities of Athens. 4 vols. London:1762, 1787, 1784, 1816.

29. Winckelmann, Johann Joachim (1717 – 1768).Gedanken über die Nachahmung der griechischen Werke in der Malerei und Bildhauerkunst. Dresden/Leipzig: 1755.

30. Winckelmann, Johann Joachim (1717 – 1768).Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums. Dresden: 1764.2nd edition 1776.

31. Espagne, Michel, Bénédicte Savoy, and Céline Trautmann-Waller. Franz Theodor Kugler: Deutscher Kunsthistoriker und Berliner Dichter. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2010.

32. Heck, Kilian. "Die Bezüglichkeit der Kunst zum Leben: Franz Kugler und das erste akademische Lehrprogramm der Kunstgeschichte." Marburger Jahrbuch für Kunstwissenschaft 32 (2005): 7 – 15.

33. Karge, Henrik. "Projecting the future in German art historiography of the nineteenth century: Franz Kugler, Karl Schnaase, and Gottfried Semper." Journal of Art Historiography 9 (2013): 1 – 26.

34. Schneider, Donald David. The Works and Doctrine of Jacques Ignace Hittorff 1792 – 1867. 2 vols. New York: Garland, 1977.

35. Schneider, Réné. Quatremère de Quincy et son intervention dans les arts (1780 – 1830). Paris: 1910.36. Wallraf-Richartz Museum. Jakob Ignaz Hittorff.Ein Architekt aus Köln im Paris des 19. Jahrhunderts.Cologne: Locher, 1987.

Repainting Antiquity: The 19th-century Architectural Polychromy Debate Seen through "German" Eyes: Hittorff, Semper, Kugler and Their Generation (2)

The paper investigates the 19th-century dispute over polychromy that revolutionized contemporary understandings of antiquity, especially ancient Greek and Roman temple structures. The Prussian, Bavarian, and German-born French architects discussed in this paper played a key role in this process, despite "Germany" as a nation only becoming a driving force in the formulation of architectural theory at a relatively later stage. The paper places the debate within the larger context of the time, subsequently analyzing conf l icting theories regarding the highly disputed but undeniable fact of polychromatic classical architecture.This re-visioning of the debate surrounding polychromy of antiquity will serve to improve our understanding of modern Greek revival architecture and even more so, our understanding of Western historiography on Chinese architecture.

19th-century European polychromy dispute,ancient Greek architecture, colors, Aphaia Temple,Parthenon, Ignaz Hittorff, Gottfried Semper, Franz Kugler,Johann Joachim Winckelmann, James Fergusson

国家自然科学基金资助项目(批准号:51678325)

清华大学自主科研计划(批准号:20151080466)

清华大学建筑学院

2017-08-18