古迹重绘

——“德意志”视角下的彩饰之辩:希托夫、森佩尔、库格勒与他们这一代 (上)

2017-09-29荷雅丽李路珂AlexandraHarrerLILuke

荷雅丽,李路珂 /Alexandra Harrer, LI Luke

蒋雨彤 译,李路珂 校 /Translated by JIANG Yutong, Revised by LI Luke

古迹重绘

——“德意志”视角下的彩饰之辩:希托夫、森佩尔、库格勒与他们这一代 (上)

荷雅丽,李路珂 /Alexandra Harrer, LI Luke

蒋雨彤 译,李路珂 校 /Translated by JIANG Yutong, Revised by LI Luke

19世纪的一场关于建筑彩饰的论争颠覆了我们对于古典建筑,特别是古希腊和古罗马神庙建筑的认知。作为建筑理论领域较为后起的一支力量,“德意志”在这一过程中扮演了特殊的角色。本文详细回顾了这场论争的来龙去脉,各派学说如何卷入其中,又如何在特定的社会机制下推动着事实的逐步揭示,最终达到观念的彻底改变。这一事件直接地影响到现代希腊复兴建筑,甚至也波及到西方的中国建筑史编纂学。

19世纪欧洲彩饰之辩,古代希腊建筑,建筑色彩,阿法雅神庙,帕提农神庙,伊格纳茨·希托夫,戈特弗里德·森佩尔,弗朗兹·库格勒,约翰·约阿希姆·温克尔曼,詹姆斯·弗格森

国家自然科学基金资助项目(批准号:51678325)

清华大学自主科研计划(批准号:20151080466)

National Natural Science Foundation of China (project number 51678325)

Tsinghua University Individual Research Fund (project number 20151080466)

1 导言

色彩,素来是一种直击情感、富有力量的表现手段。然而,西方古典时期的雕塑与建筑是否有可能采用色彩装饰?或者,具体来说,古希腊神庙是否存在彩饰?如果答案是肯定的,它们的色彩是明艳的还是淡雅的?这些问题在西方的学术圈和普通大众之中屡屡引起激烈的讨论。从19世纪初期问题的提出直到现在,关于此话题的讨论不断涌现,在1830年代成为令人瞩目的热点——当时人们在希腊神庙建筑上发现了残存的颜料痕迹,这一发现颠覆了欧洲人对古典建筑偏好“纯净”的色彩认知。[1]6

本文将详细回顾这场关于彩饰的论争,它的来龙去脉与论争焦点,并探究论争背后的社会机制,以及卷入其中的各派势力。我们试图回答以下问题:在何时发生了何事;通过这一事件我们能够有何领悟;以及在跨文化的语境下,这场论争对于过去和现在有着怎样的重要性。换言之,我们将首先介绍几位在辩论中扮演了重要角色、却尚不为中国读者熟知的关键人物,然后分析他们之间的关系,最后在宏观的时代背景下讨论这些人物,以理解他们对于世界建筑史的重要意义。

本研究主要基于德语及英语的文献资料,在这场重新定义古典建筑色彩的运动中,本文聚焦于“德意志”的角色,也兼顾了在其中作出贡献的普鲁士,巴伐利亚及德裔法籍建筑师们。

2 序幕——阿法雅神庙的色彩复原

2.1 18世纪,单色眼镜下的“古典”建筑——温克尔曼的希腊建筑史观

德国艺术史家、“考古学家”1)约翰·约阿希姆·温克尔曼(1717–1768),是18世纪末期新古典主义运动的领导者。这场运动重新诠释了古典建筑,以及文艺复兴对古典的诠释。将“高贵的单纯”和“静谧的伟大”作为完美艺术的唯一准绳,这是温克尔曼的著名论断,这一论断最初成型于他的论文《关于绘画和雕刻中模仿希腊艺术作品的思考》(1755),并在《古代艺术史》(1764)一书中发展完善。温克尔曼的这一论断将形式和构成作为古典美的决定性因素,为后世树立了一个标准(尽管温克尔曼和他同时代的人对希腊艺术和建筑的认识仅仅来源于古罗马人的复制品2))。温克尔曼虽然已经知道古典文献中有彩绘雕塑的记载,却不屑地宣称这种“野蛮的习俗”属于一个更原始的早期阶段,例如就意大利艺术而言,这一做法就源自伊特鲁里亚艺术。他推崇白色(白色大理石的色彩),因为白色充分地反射光线、最能凸显造型的美感3)。此外,在这场古典主义者对白色的狂热崇拜中,“形式”和“色彩”有如两性的对峙,一边是阳刚/理智(抽象的“纯粹”形式),另一边则是阴柔/情感(感性的色彩)[2]288。正是这一观念导致欧洲人(不仅限于德语国家)对古典建筑的误解持续了将近一个世纪,直到某些证据逐渐丰满起来,它的权威才开始动摇。

2.2 考古实例与发现

自18世纪下半叶开始,关于古代著名遗迹与古遗址的著作日渐丰富,其中以英语和法语作品为多4):

1762–1816年,苏格兰考古学家詹姆斯·斯图尔特(1713–1788)与英格兰业余建筑师尼古拉斯·雷维特(1721–1804)联合出版了关于雅典古代建筑的详细测绘成果(《雅典的古迹》,四卷本,分别出版于1762年、1787年、1784年、1816年)5)。

1764年,英国新古典主义建筑师罗伯特·亚当(1728–1792)出版著作《位于达尔马提亚的斯普利特的戴克里先皇宫遗迹》。1743–1745年,意大利艺术家乔瓦尼·巴蒂斯塔·皮拉内西(1720–1778)发表了一批关于罗马及其古典建筑复原想象的版画(《建筑与透视第一卷》, 1743;《古代与现代罗马的景象集》,1745)6)。

1 拉奥孔与儿子们,著名古希腊雕塑,可代表温克尔曼的艺术观点“高贵的单纯与静谧的伟大”(梵蒂冈美术馆藏;摄影:李路珂)/Laocoön and his sons, famous ancient Greek sculptures that embody Winkelmann's doctrine of"noble simplicity and calm grandeur" (Vatican Museum; photo by LI Luke)

1 Introduction

Color has always been a powerful means of expression that has infamed emotions. In the West,the issue of the mere possibility of polychromy of antique sculptures and buildings – whether or not ancient Greek temples were painted and if so, whether the colors were bright or dull – has repeatedly caused a stir both in academic circles and among the general public. A perpetual issue from its emergence at the beginning of the 19th century to the present, it heated up in the 1830s, when the discovery of paint remains on Greek temples revolutionized the European perception of classical architecture as monochrome (white) walls.[1]6

In this paper, I discuss the path of the polychromy dispute and its intensity, and investigate the mechanisms of the debate as well as the conficting parties involved, with a view to answering the questions of what happened (chronology of events), what lessons we can learn from this/what insights we can gain (historical mindset; French-German aesthetics), and what signifcance it had and still has in a global context (Greek revival architecture;understanding of Western historiography on Chinese architecture). That is to say, I will frst introduce the key players of the debate because they are hardly known in China, and then explain their relations with each other, before placing them in the larger context of the time with the goal to understand their signifcance to global architectural history.

Research is based on data available only in German (and English) and focuses on the role of"Germany" and the Prussian, Bavarian, and Germanborn French architects engaged in repainting the picture of antiquity.

2 Setting the stage – The colorful recovery of the Aphaia Temple

2.1 Distorted view of antiquity in the 18th century – Winckelmann's misconstrued monochromy for ancient Greek architecture

The German art historian and "archaeologist"1)Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-68) shaped the neo-classical movement of the late 18th century that challenged antiquity and its interpretation in the Renaissance. His doctrine of "noble simplicity and calm grandeur" (edle Einfalt und stille Groesse) as the sole yardsticks of artistic perfection, frst formulated in Gedanken über die Nachahmung der griechischen Werke in der Malerei und Bildhauerkunst (1755) and elaborated in Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums(1764), set the benchmark for succeeding generations,identifying form and composition as decisive factors for classical beauty. (Even though Winckelmann and his contemporaries knew Greek art and architecture only from Roman copies. ) Although aware of painted sculptures mentioned in classical texts, Winckelmann derogatively explained away this "barbaric custom" as belonging to an early primitive stage or, in the case of Italian art, to Etruscan art – he glorifed the color white (as in white marble) that acted as a catalyst and refected light so as to best highlight the beauty of form. Moreover, in the classicist cult of the white,"form" and "color" were powers in the battle of the sexes, reflecting the oppositions of the masculinerational (abstract "pure" form) and the feminineemotional (sensual color), respectively.[2]288And it was this mind-set that led to a misconstrued perception of antiquity in Europe (not only in the Germanspeaking realm) for almost a century, until a growing body of factual evidence challenged its authority.

2.2 Archaeological facts and fndings

Writings about famous ancient monuments and sites have been the order of the day since the 2nd half of the 18th century, with the English and French at the forefront.4)

The Scottish archaeologist James Stuart (1713-1788) and the English amateur architect Nicholas Revett (1721–1804) together published exact measurements of the buildings of Athens (Antiquities of Athens, 4 vols, 1762, 1787, 1784, 1816).5)

The British neo-classical architect Robert Adam(1728-1792) published his Ruins of the Palace of the Emperor Diocletian at Spalatro in Dalmatia (1764).The Italian artist Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-78) published his etchings of Rome and fictitious interpretations of classical architecture (Prima parte di architettura e prospettive, 1743; Varie vedute di Roma antica e moderna, 1745).

Jacques-Germain Soufot (1713-1780), who later built the Panthéon in Paris (after 1755), measured the Greek ruins at Paestum (his survey results were published some years later in: Gabriel-Pierre-Martin Dumont, Les Ruines de Paestum, 1764).6)The French artist and draftsman Charles-Louis Clérisseau (1721-1820) published a work about the Roman monument in Nîmes (Antiquités de la France, prèmiere partie:monumens de Nismes, 1778). The German historian Karl Hammer (1969-), biographer of the Cologne-born French architect Jakob Ignaz Hittorf (1792-1867), a key fgure in the polychromy debate, sarcastically asked whether it was really possible that nobody in this vast group of professional and amateur archaeologists had noticed any traces of color on ancient sculptures or buildings.[3]101

As a matter of fact, early archaeologists discovered and documented traces of paint on structural and decorative architectural components in Egypt, Greece, and southern Italy from the 1820s onwards, but "little had made of them" as the American architectural historian David van Zanten argued.[4]268And yet, some of them were aware of the relevance and far-reaching significance of their findings, as is evident in the letters about Greece written by the German architect Karl Haller von Hallerstein (1774-1817).[2]79However, the question of whether or not buildings had been painted, in antiquity, was too complex and had to be gradually resolved by generating awareness among the general public.[1]6Crucial pieces still had to be found before the polychromy puzzle was able to be pieced together into a comprehensive theory (Hittorf; Semper).

The Aphaia Temple, situated on the small island of Aegina in the Saronic Gulf, twice played a crucial role in the process of the rediscovery of antique polychrome architecture: in the early 19th century and in the 20th century. The late Archaic temple dedicated to the local Greek goddess Aphaia(500 BCE) was formerly associated with Jupiter Panhellenius, because it was mistaken for an earlier temple built around 570 BCE on the same site but destroyed in 510 BCE.[1]6Known to the English public through being mentioned in Ionian Antiquities (Richard Chandler, Nicholas Revett,William Pars; 1769-1797), the Doric temple was studied and excavated in May 1811 by Haller – a protégé of the art patron and Bavarian crown prince Ludwig (who would soon become King Ludwig I,and reign from from 1825-1848) – and his traveling companion, the English architect Charles Robert Cockerell (1788-1863).

不久后,雅克·赫尔马因·苏夫洛(1 7 1 3–1 7 8 0),即1 7 5 5年后设计建造巴黎万神庙的建筑师,对帕埃斯图姆的古希腊遗址进行了测绘(其调查成果数年后发表于加布里埃尔·皮埃尔·马丁·迪蒙的《帕埃斯图姆的古遗址》,1 7 6 4)。1 7 7 8年,法国艺术家、绘图师查尔斯·路易·克莱里索(1 7 2 1–1 8 2 0)发表了一幅关于尼姆罗马古迹的作品。(《法兰西古迹之一:尼姆的遗迹》,1778年)面对这些为数众多的专业或业余的考古学者,德国历史学家卡尔·哈默(1969–)曾不无讽刺地质问:他们难道真的没有一个人注意到,在古代的雕塑或建筑上有着色彩的踪迹?[3]101(哈默是这场彩饰之辩的关键人物、生于科隆的法国建筑师雅各布·伊格纳茨·希托夫的传记作者。)

事实上,自1820年代开始,早期考古学者们就已发现并记录了出现在埃及、希腊及意大利南部的建筑结构及装饰部件上残存的彩饰痕迹,但正如美国建筑史学家戴维·范·赞特恩所言:“他们视而不见”[4]268。然而,在他们之中还是有人意识到了这些发现的内在联系,及其背后的深远意义,这在德国建筑师卡尔·哈勒尔·冯·哈勒施泰因(1774–1817)[2]79关于希腊的信件中有着明确的表述。可是,古典建筑究竟是否存在彩饰,这个问题及其相关的观念已经过于盘根错节、深入人心,乃至于只能采取曲折的方式,通过唤醒普通大众的关注和认知来渐次解决[1]6。在有关彩饰法的种种线索被拼凑在一起并形成一个可以理解的理论体系(如希托夫、森佩尔)之前,还需要找到一把解开迷团的关键钥匙。

位于爱琴海的萨罗尼克湾,距雅典约40km的埃伊纳岛上的阿法雅神庙,曾于19世纪早期和20世纪先后两次在重新发现古代彩饰建筑的历程中扮演了关键性的角色。这座古典时代晚期的神庙用于祭祀希腊地方女神阿法雅(约公元前500年),阿法雅神庙曾与其基址上原有的一座大约公元前570年建成、公元前510年毁去的宙斯神庙混淆,因此阿法雅神庙曾经被误认为与希腊主神朱庇特有关[1]6。这座多立克式神庙由于被理查德·钱德勒等人1769–1797年出版的《爱奥尼亚的古代遗迹》一书所述及而进入英语读者的视野。1811年5月,它迎来了两位发掘者——一位是哈勒尔,巴伐利亚皇储、艺术资助人路德维希(后来成为路德维希一世大帝,1825–1848年在位)的门客,另一位是哈勒尔的旅伴,英国建筑师查尔斯·罗伯特·科尔雷尔(1788–1863)。

他们发现了一些从山花上脱落的雕饰残片(现藏于慕尼黑古代雕塑博物馆),这些残片上有着明显被涂绘过的痕迹。这座神庙残片的发现之所以特别重要,是因为神庙的大部分被掩埋在土里,这使得它的明艳色彩被意外地完好保存下来(尽管这些色彩一旦暴露于空气中便迅速地褪去)[4]266。

巴伐利亚王储从哈勒尔1811年12月的来信中得知了埃伊纳岛的这座神庙的大理石碎片,并于1812年11月1日在一场拍卖会上将其买下[2]11。尽管哈勒尔从未正式发表过他的发现(他于1817年死于希腊),但那些残片的实物与他的住所中找到的速写上的记录彼此一致。

这个小小的发现有着极其深远的影响。它不仅为带有彩饰的古典建筑在物质实体层面进行的视觉复原(完全模仿原物制造的复制品)铺平了道路,更为其后19世纪建筑设计(新希腊式建筑或希腊复兴建筑)中彩饰法的运用奠定了基础[5]278。

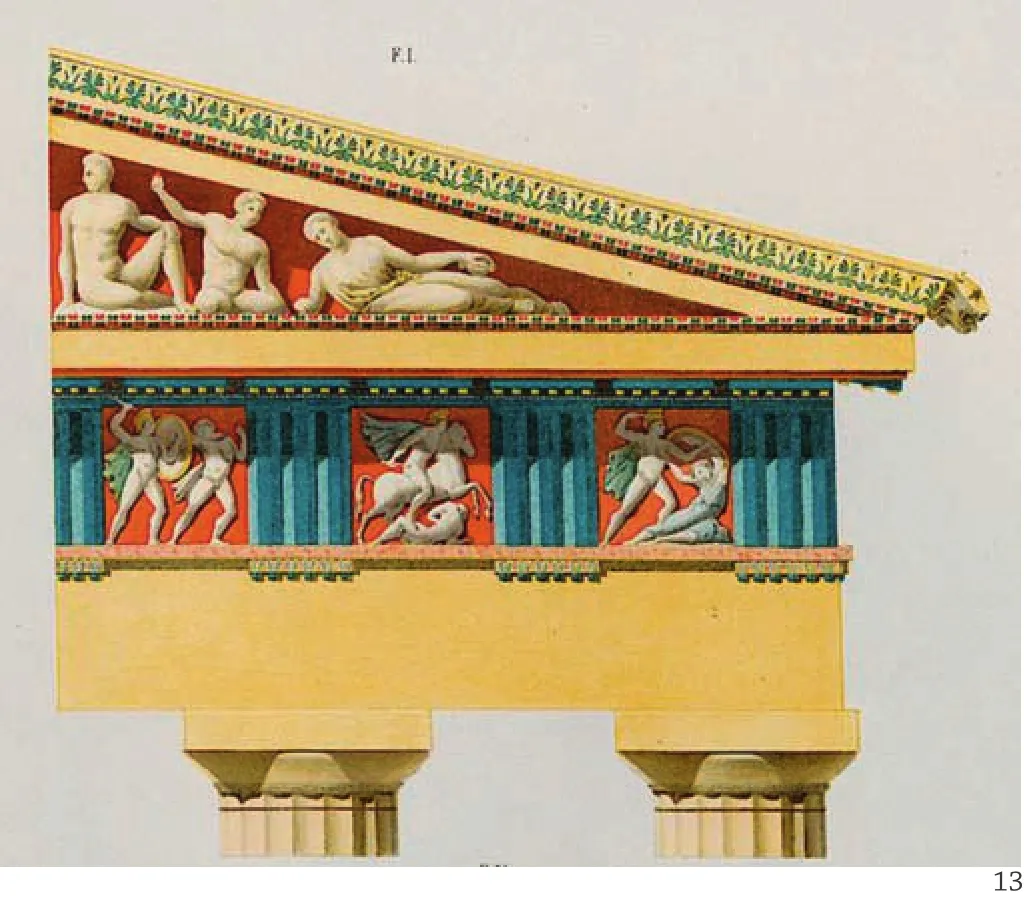

2.3 视觉上的复原——模仿性重建与想象

莱奥·冯·克伦策 (1784-1864),巴伐利亚王储路德维希的宫廷建筑师,尽管在1816年已有了一个意向性的计划7),但直到10余年后才实现他的勃勃雄心——复原重建慕尼黑古代雕塑博物馆收藏的阿法雅神庙西山墙,借此提升带有彩饰的古典建筑的视觉效果与社会认知(1816–1830年,置于埃伊纳展厅,1828年完成)。克伦策在慕尼黑设计的这座“彩饰博物馆”,主要功能是放置路德维希关于希腊和罗马雕塑的皇家收藏,同时也是路德维希把慕尼黑城变成“德意志的雅典”的理想图景的一个部分。

这项复原工作持续了数年。其初稿的诞生(1822)基于哈勒尔和科尔雷尔绘制的速写,1828年,又根据哈勒尔的另一位旅伴奥托·冯·斯坦科尔伯格(1786–1837)到慕尼黑旅行时提供的信息进一步完善[2]80。克伦策的复原成果,那饱和而强烈的色彩引来了同时代人的批评,甚至科尔雷尔本人在1840年到访慕尼黑时都曾表达了自己的顾虑[2]81。但我们不应忘记,在那时,这场即将发生的彩饰之辩中的两位关键人物,即希托夫和森佩尔,都还没有开始他们的伟大旅行,科尔雷尔也尚未发表他的第一手报告(报告发表于1860年,在他的实地勘察近半世纪以后 )。

1846年,科尔雷尔的朋友希托夫为阿法雅神庙提出了一个合理的复原设计。尽管希托夫从未真正到访过希腊本土,他在实地考察意大利南部的希腊殖民地20年之后提出的这一视觉化的复原似乎是可信的:他将正面山花下沿的卷须饰移至门廊的内部(内殿),从而修正了克伦策的主要错误之一。

1860年,也就是15年后,科尔雷尔发表了一个色调更加淡雅的复原设计,这一作品用粉彩绘制,保持了一种优雅而内敛的气质。事实上,或许由于时代审美观的变化,以及19世纪下半叶对于饱和色调所持的愈演愈烈的批判态度,这一版复原设计与他和哈勒尔1811年的原始手稿有着微妙的差别[2]84。

纸上的复原作品一时间百花齐放,这要归功于巴黎美术学院8)丰厚的旅行奖学金。一些赢取了著名的罗马大奖的获奖者在罗马的法兰西学院学习古典艺术与建筑学,在这一时期受到希托夫的启发,创作了上色的测绘图,以及带有彩饰的古代建筑复原设计图。这些工作更多地属于建筑幻想的范畴,而非科学的复原设计[4]260。

其中特别值得一提的例子是法国青年建筑师夏尔·加尼耶(1825–1898),他是1848年罗马大奖的获得者。在他的作品中,尽管地砖的红色或多或少是受其原始色彩的启发,但控制着整个立面的厚重饱满的色彩使得加尼耶的阿法雅神庙复原设计饱受争议。他的复原设计于1853年在罗马法兰西学院展出(1854年出版了一部分,1884年全部出版),与哈勒尔和科尔雷尔的版本形成了鲜明的对比。

加尼耶的复原设计值得特别的关注,这是因为他在1852年亲自到访过埃伊纳岛——自1845年起,奖学金获得者们得以游历结束了战事的希腊和土耳其9)。不出所料,当时已成为巴黎美术学院院士的希托夫对这一复原提出了批评,而他的老对头,法国考古学家、巴黎美术学院常务部长劳尔-罗谢特(1790–1854)却给予了赞扬。具体的批评主要集中在额枋上方的多立克式檐壁上用以填充三陇板间隙的长方形陇间壁:复原设计中的这些饰以浓烈色彩的构件(纯粹)是想象的产物。此外,那些曾经被希托夫成功地移走的卷须饰,又重新出现在了建筑的正面——这种直白的挑衅或许正是招致希托夫批判的原因。

1901年,阿法雅神庙在首次被发现的百年之后,又一次成为学术界关注的焦点。这一次,雅典德国考古学院的主任阿道夫·富特文勒(1853–1907)对神庙实施了一次系统的田野发掘,他的团队成员恩斯特·菲克特(1875–1948)制定了至今仍被认为合理的色彩复原准则[6]。

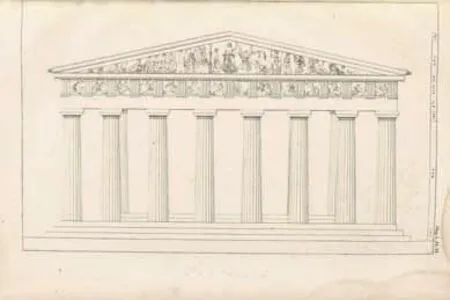

2 18世纪末期的考古实例与发现:帕提农神庙西立面(斯图尔特与雷维特,《雅典古代建筑》,卷2,图版6)/Archaeological facts and fndings in the late 18th century,Parthenon west facade (Stuart and Revett, The Antiquities of Athens, vol. 2, plate 6)

3 位于希腊萨罗尼克湾的埃伊纳岛上的阿法雅神庙遗址现状(图片来源:维基公共资源)/Aphaia Temple on the island of Aegina in the Saronic Gulf, Greece, current condition of the site (Source: Public domain work, www.commons.wikipedia.org)

4 阿法雅神庙遗址出土的带有色彩痕迹的构件残片 (引自《色彩里的神》,图版116)/Fragment of the Aphaia Temple with traces of color (Brinkmann,Bunte Götter, fgure 116)

They discovered fragments of fallen pediment sculptures (now stored in the Munich Glyptothek)that had clearly originally been painted. The discovery of the fragments of this temple was so important because the temple had been largely buried, so that its bright colors were exceptionally well preserved(although they vanished rapidly upon exposure to the air).[4]266The Bavarian crown prince, who learned about the Aegina Temple marbles through Haller's letter from December 1811, bought them at an auction on November 1, 1812.[2]11Although Haller never published his findings (he died in Greece in 1817), the physical fragments are in accordance with sketches from his estate.

This small discovery had far-reaching consequences and paved the way towards the visual recovery of painted buildings from antiquity in physical form (imitative reproductions made to look"exactly" like the original) and subsequently the use of color in contemporary 19th-century architectural design (neo-Grec or Greek revival architecture).[5]278

2.3 Visual recovery – Imitative reconstructions and fantasies

Although a tentative plan already existed in 1816,7)it was only a decade later that Leo von Klenze (1784-1864), court architect of the Bavarian crown prince Ludwig, realized his ambition to enhance visibility and recognition of the polychrome architecture of antiquity through the restoration of the western pediment of the Aphaia Temple housed in the Glyptothek (1816-30; installed in the Aegina Hall, completed 1828; with the original pediment sculptures against the background of the temple façade newly reconstructed in plaster), the"Polychromy Museum" he designed in Munich to house Ludwig's royal collection of Greek and Roman sculptures and as part of Ludwig's vision, which was to transform the city into a "German Athens".

The project grew steadily over the years,developing out of a first draft (1822) based on Haller's and Cockerell's hand sketches and further elaborated in 1828 by information provided by Otto von Stackelberg (1786-1837), one of Haller's traveling companions, when he came to Munich on his travels.[2]80Klenze's contemporaries criticized the fnal result for its saturated, intense colors; and even Cockerel voiced his concern during his 1840 Munich visit.[2]81However, we should not forget that neither Hittorf nor Semper, both key fgures in the polychromy debate to come, had gone on their great tours yet, nor had Cockerel yet publicized his frsthand report (this was subsequently published in 1860, half a century after his on-site research).

In 1846, Hittorff, a friend of Cockerel's, put forward a rational reconstruction of the Aphaia Temple. Despite the fact that he had never actually visited Greece, his visual recovery – two decades after his field trip to the Italian Greek colonies in southern Italy – was plausible, correcting one of Klenze's major mistakes by repositioning the spiraling tendril away from the lower edge of the front pediment to the interior of the portico (i.e.cella front).

Fifteen years later, in 1860, Cockerel's published reconstruction appeared comparatively light, in pastel colors, and remained elegantly reserved. In fact, it differed slightly from his and Haller's original 1811 sketches, probably because of the changed taste of the time and the more critical attitude towards bright colors in the 2nd half of the 19th century.[2]84

Paper reconstruction assumed truly extreme dimensions thanks to the generous travel stipends provided by the Académie des Beaux-Arts:8)having won the prestigious Prix de Rome (Rome Prize), the pensionnaires at the Académie de France à Rome(French Academy in Rome) studied classical art and architecture and, inspired by Hittorf, produced colored documentary (survey) drawings and recovery plans of ancient polychrome monuments that more often than not belonged to the category of architectural fantasy and not scientifc restoration.[4]260

One particularly telling example is that of the young French architect Jean-Louis Charles Garnier(1825-98), winner of the 1848 stipend. Although the red of the foor tiles was loosely inspired by their original color, the dark, heavy colors that control the elevation of Garnier's highly controversial Aphaia Temple, displayed at the Académie in 1853(published in a partial version in 1854 and fully only in 1884), was in sharp contrast to Haller and Cockerel's version.

This is even more remarkable because Garnier visited Aegina in 1852 – since the pensionnaires had been allowed to travel around now-peaceful Greece and Turkey since 1845.9)Not surprisingly,Hittorff, by then a member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, voiced criticism, whereas Hittorff's old adversary Desiré-Raoul Rochette (1790-1854),French archaeologist and Perpetual Secretary(Secrétaire Perpétuel) of the Académie, praised the work. Specifc criticisms focused on the rectangular metops that fll the space between triglyphs in the Doric front frieze above the architrave: decorated and painted in heavy colors, they were (quite simply)products of the imagination. Additionally, the spiraling tendril appeared again at the front of the building, whence Hittorf had successfully removed it – a direct afront and probably the reason for his criticism.

Almost a hundred years after its frst discovery,the Aphaia Temple was again the focus of academic attention. In 1901, the director of the German School in Athens, Adolf Furtwängler (1853-1907),carried out a systematic site excavation, and Ernst Fiechter (1875-1948), a member of Furtwängler's team, formulated the principles for color reconstruction that are still considered valid today.[6]

The main difference with regard to previous recovery attempts is the color of the vertical elements of the Doric order, namely mutules,triglyphs, and regulae: as new fragments showed,they were black – not blue, as hitherto assumed by all, including Haller. (And thus, according to Fiechter's premise, the previously-discovered blue regula stored in the Glyptothek must belong to the[interior] cella façade (and not the [exterior] temple front façade) – a fact subsequently confrmed by the 2nd German excavation [1966-1979] under Diert Ohly.)

Finally, the digital model by the archeologist Valentina Hinz and the architect Stefan Franz, who run a building history and visualization company in Munich, generated a century later, almost two-hundred years after Haller's field survey,summarizes the state-of-the-art of the polychromy of archaic Doric temples.[2]87Columns coated with thin limestone-marble stucco in white stand atop a (fine-pored limestone) tiered base/podium; the vertical frieze elements of mutules, triglyphs, and regulae were black, and separated from one another by an ocher red horizontal fillet molding (taenia)to highlight the structural logic of the entablature;and although the original metopes have been lost(presumably stolen by Roman thieves), based on those of the older temple, they were probably white marble reliefs with black headbands.

Everything below the horizontal cornice(geison) was white, black, or red; only the rear wall of the pediment above was painted in Egyptian blue. Although the colors of the roof are unclear, the German archeologist Vinzenz Brickmann (1958-),whose research results were shown in a worldwide touring exhibition (Bunte Götter–Die Farbigkeit antiker Skulptur [Gods in color–the polychromy of ancient sculpture], 2003-15), suggested that they were azure (blue), vermillion (red), and malachite green.[2]88Entering the temple from the east and looking up, one noticed that the colors were noticeably brighter than on the outside, to make up for the shadowed vestibule.

与此前的尝试相比,此次复原的主要特色是根据发现的新残片,确定了多立克式的竖向构件,即檐托、三陇板,以及滴珠饰板,实际上是黑色而非蓝色——这与此前包括哈勒尔在内的所有人的观点都不同。[如果菲克特的这个前提成立,那么此前发现并藏于慕尼黑古代雕塑博物馆的蓝色滴珠饰板无疑是属于(位于门廊室内的)内殿立面的一部分,而非建筑的外立面——其后戴尔特·奥利主持的第二次德国人的挖掘(1966–1979)证实了这一点。]

最近,在慕尼黑经营一家建筑历史和数字影像公司的考古学者瓦伦蒂娜·希恩兹与建筑师斯蒂芬·弗朗兹在一个世纪后,即哈勒尔田野调查的将近200年后,为古典时期多立克神庙的彩饰法制作了一个概括最新艺术研究进展的数字化模型[2]87。在这个模型中,柱子上覆盖了一层薄薄的由石灰石和大理石混合而成的白色灰泥涂层,立于细孔状石灰岩的多层台基之上;竖向的檐壁构件,檐口托饰、三陇板和滴珠饰板是黑色的,且被赭红色水平饰带(束带饰)隔开,以强调檐部的结构逻辑;而尽管原来的陇间壁已经丢失了(可能是被古罗马扒手盗走的),根据更古老的神庙的陇间壁推测,它们可能是顶部带有黑色饰带的白色大理石浮雕。

所有位于水平檐口下方的构件都是白色、黑色或红色的,只有山墙内壁被涂成埃及蓝。屋顶的颜色尚不确定,德国考古学家温岑茨·布里克曼(1958–)提出它可能是由石青、朱砂红以及孔雀绿所饰[2]88。他的研究成果曾展示于一个全球巡回的展览中(《色彩里的神——古典雕塑的彩饰》,2003–2015)。当人们从东面步入神庙并仰望时,会发现前廊内部的色彩比室外要明艳许多,这或许可以弥补前廊光线的不足。

5 阿法雅神庙西山墙,希托夫复原设计(图纸左侧的名称标注为本文作者所加)(希托夫,《赛林努特的恩培多克勒神庙复原》,图版8左侧)/Western pediment of the Aphaia Temple, reconstructed by Hittorf (with a legend identifying the various parts of the pediment on the left) (Hittorf,Restitution du temple d'Empédocle à Sélinonte, plate 8, left)

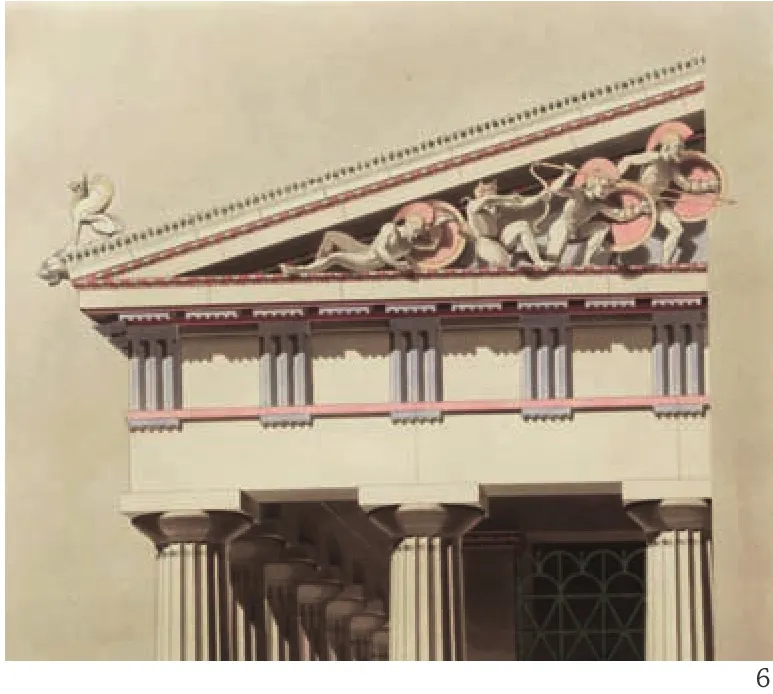

6 阿法雅神庙东山墙,科尔雷尔复原设计(科尔雷尔,《埃伊纳的宙斯庙》,图版6)/Eastern pediment of the Aphaia Temple, reconstructed by Cockerell (Cockerell, The Temples of Jupiter Panhellenius at Aegina, plate 6)

7 阿法雅神庙平面图(左)、东山墙立面图(右),加尼耶复原设计(加尼耶《埃伊纳的宙斯神庙》 图版9、10)/Plan (left) and Eastern pediment(right) of the Aphaia Temple, reconstructed by Garnier (Garnier, Temple de Jupiter Panhellénien à Egine, plates 9 and 10)

3 慢慢接受惊人的事实——关于彩饰的激辩

3.1 开端——学派之争

德籍或德裔的考古学家、建筑师、艺术资助人以及历史学家们在阿法雅神庙的发掘和(视觉)复原上起到了主导作用,不管是在实体空间还是在数字化的虚拟空间均是如此。然而,尽管他们的确凭借自己的努力做出了具有开创性的重要贡献,但对于在实质上修正西方史学编纂中的古希腊建筑彩绘这样一个更宏观也更复杂的挑战来说,这依然是一个很小的组成部分。而后者经历了长达10年的、法德两地主要学者之间的激烈辩论。

3.1.1 考特梅尔·德·坎西,彩饰法的初步展开

1815年,法国雕塑家、空想考古学家及政治家德·坎西(一位天主教保皇党人,在法国大革命中曾因此被判处死刑,但不久便被无罪释放),撰写了一本具有论辩性质的小册子(《奥林匹亚的朱庇特》),在论及着色的古代雕塑时,附了一些手绘上色的插图。这本书引发了关于古希腊艺术中彩饰的辩论,并很快成为此后一系列研究的重要参考10)。

考特梅尔在1816–1839年曾是巴黎美术学院位高权重的常务部长,在位期间还掌管了罗马大奖的评定工作,该奖的一些获得者后来成为彩饰之辩中的重要人物。1818年,考特梅尔成为了法国国家图书馆的考古学教授。他最有名的著作是两卷本的《建筑学辞典》(1789年,1832年)。考特梅尔将建筑学理论与实践的源头上溯至古希腊,“随后由古罗马人发扬光大,并成为整个文明世界的财富”。但他却将丰富的古希腊建筑限定于一种非黑即白(理想主义)的类型学11):

希腊神庙是希腊人哲学智慧的具象化表达,也是一个绝对固定的语言学结构,仅通过不同的柱式(词汇)被归类于3个样式体系(多立克式、爱奥尼式与科林斯式)。在希腊神庙的内部,彩饰最好的表现方式是在雕塑上手工单色平涂(而非绘画),因为有些许瑕疵和固有色的大理石被看作是“真实的”,而没有绘画的那种模仿的意图及虚幻的效果[1]16。这微妙的区分反过来体现了考特梅尔根深蒂固的保守观念,以及全方位理解“彩饰”概念时的无能。作为那个时代巴黎美术学院学院派古典主义理想主义者的主要代表,考特梅尔认为在坚守严格的古典规范方面,他有着义不容辞的责任(德式温克尔曼传统)[5]104。

3.1.2 希托夫,关于古希腊彩饰法的系统理论

出生于科隆的巴黎建筑师雅各布·伊格纳茨·希托夫(1792–1867),曾经(实至名归地)宣称自己是“在各个时期的希腊建筑中,在各种壮丽的神话故事的丰富细节中发现了使用色彩作为装饰”的第一人[3]104。希托夫实际上是古典建筑从单色到彩色的观念转变背后的先驱者。他建立了关于古典时代彩饰建筑的第一个全面的理论,其中还提出了关于色彩装饰的规则[5]49-50。尽管希托夫自己也是一个古典主义者,但他不像考特梅尔那样囿于循规蹈矩的古典主义观念,而将彩饰的运用解释为“对于被装饰的柱式的固定语言所进行的系统化的微调和丰富化”[4]272。

希托夫作为一个专业建筑师的成功,就算不全是,也很大程度上依赖于他对装饰与装饰设计的敏感性,而这种敏感性正是他在彩饰法之辩的过程中通过搜寻大量的古典建筑彩饰实物而获得的。起初他在弗朗索瓦-约瑟夫·贝朗格(1744–1818)的手下担任绘图员,并于1818年接任他成为法兰西政府建筑师。此后他开始从事皇家庆典和纪念活动的策划(直到1830年的法国七月革命),并一度成为巴黎上流社会最青睐的建筑师12)。1833年,他正式成为曾经就读的巴黎美术学院的院士之一。

8 阿法雅神庙三陇板局部(左)、东山墙(右),富特文勒复原设计 (富特文勒,《埃伊纳:阿法雅圣地》,图版61上部,104、105底部)/ Triglyphs (left) and eastern pediment (right) of the Aphaia Temple, reconstructed by Furtwängler (Furtwängler, Aegina: Das Heiligtum der Aphaia,plate 61 [top], plates 104 and 105 [bottom])

9 瓦伦蒂娜·希恩兹与斯蒂芬·弗朗兹所作的阿法雅神庙数字化复原模型/ Digital reconstrucion of the Aphaia Temple, 3D model by Valentina Hinz and Stefan Franz (Source: Ofcial website of the Büro für Bauforschung und Visualisierung,http://www.hinzundfranz.de/dt/dtbei/dtbaph.htm)

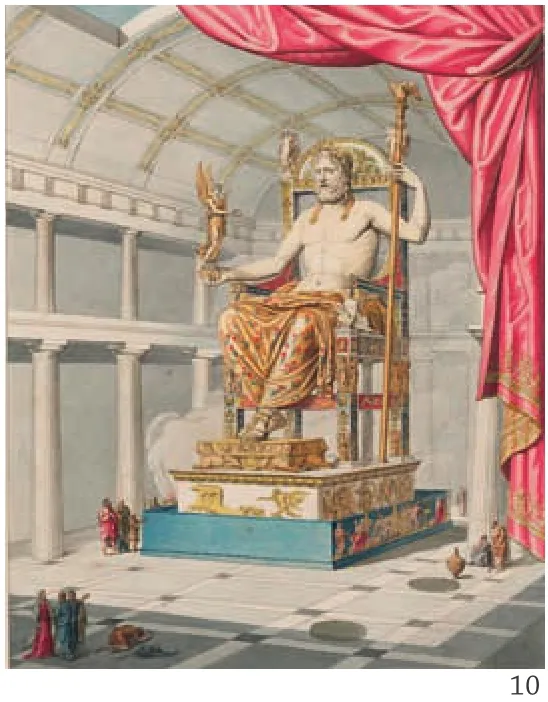

10 位于希腊雅典的奥林匹亚宙斯神庙内的彩饰雕塑,公元前6世纪至公元前2世纪(考特梅尔·德·坎西,《奥林匹亚宙斯》卷首页)/Colored statue from the Temple of Olympian Zeus in Athens, Greece, 6th century BC-2nd century (Quatremère de Quincy, Le Jupiter olympien, frontispiece)

3 Acknowledging the astonishing truth – The polychromy debate

3.1 The beginnings – Conflicting schools of thought

German(-born) archeologists, architects, art patrons and historians played a leading role in the discovery and (visual) recovery of the Aphaia Temple, in both physical and digital form. However,their contributions, although groundbreaking and important in their own right, were in fact only a small component of a much larger, more complex challenge –the factual rectifcation of Western historiography on polychromy in ancient Greek architecture, which took the form of a decades-long debate among the leading French and German scholars of the time.

3.1.1 Quatremère de Quincy, the tentative beginning of polychromy

In 1815, Antoine-Chrysôstome Quatremère de Quincy (1755-1849), a French sculptor, armchair archaeologist, and politician (a Catholic royalist condemned to death in the French Revolution,but acquitted in time), wrote a polemic pamphlet,illustrated with hand-colored plates, on the subject of antique colored statues (Le Jupiter olympien, 1815), which triggered the discussion on polychromy in classical Greek art and soon became the reference point for succeeding studies.10)

Quatremère held the prestigious position of Permanent Secretary (Secrétaire Perpétuel) of the Académie des Beaux-Arts from 1816-39 and during that time was in charge of awarding the Prix de Rome, the winners of which played a significant role in the polychromy debate. In 1818, he became a professor of archaeology at the National Library of France. He is best known for his Dictionary historique de l'architecture (2 vols, 1789 and 1832).Quatremère traced the origins of theory and practice of architecture to the Greeks, which "then spread by the Romans and became the property of the civilized world as a whole", but confned Greek (i.e. regular)architecture to small categories (idealist typologies):

The temple of the Greeks was as a materialization of their philosophy and an absolutely fxed linguistic construct distinguished only by the division of its order (vocabulary) into three sub-systems (Doric,Ionic, and Corinthian orders). Inside the Greek temple, polychromy in its best form revealed itself in the form of hand-dyed (not painted) sculptures,because chromatic (stained and tinted) marble was regarded as being "truthful" without pretending to imitate the illusory efect of painting.[1]16This subtle distinction reveals Quatremère's deeply-rooted conservative views and inner inability to grasp the concept of polychromy in all its dimensions. As the principal representative of idealist academic classicism in the Académie des Beaux Arts at that time, Quatremère felt obliged to uphold the rigid classicist norms (in the German Winckelmann tradition).[5]104

3.1.2 Hittorff, a systematic theory of Greek polychromy

Jakob Ignaz Hittorff (1792-1867), a Cologneborn Parisian architect, once claimed – justifiably – to be the frst person who had "discovered in Hellenistic architecture from all times the use of colors as adornment in various nuances of splendor and mythical allusions".[3]104Hittorf was in fact the pioneer behind the perception shift from monochromy to polychromy. He formulated the first comprehensive theory of polychrome architecture in antiquity that postulated the regularity of painted decoration.[5]49-50And although Hittorf was a classicist, he pushed the boundaries of Quatremère's normative classicist view by explaining the use of polychromy as "a systematic nuancing and enrichment of the fixed vocabulary of the orders it ornamented".[4]272

Hittorff's success as a professional architect depended largely if not fully on the ability in and sensitivity to decoration and ornamental design that he gained through the polychromy debate during his search for the polychrome architecture of antiquity.After working (as a draughtsman) for François-Joseph Bélanger (1744-1818) whom he succeeded as French government architect in 1818, he made a career as a designer of royal fêtes and ceremonials (until the July or Second French Revolution of 1830) and was the favorite architect of the Parisian upper class.12)In 1833, he became a member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts where he had been a student.

Driven by an interest and curiosity in archaeology, Hittorff traveled to Italy and the Greek colonies (never actually visiting Greece itself – a common way of doing things at the time),departing Paris in September 1823 and Sicily in January 1824. In Sicily, he gained first-hand experiences of Hellenistic architecture (Magna Graecia), particularly the westernmost Greek colony of Selinunte near Agrigento on the southwestern coast of Sicily.13) At the local acropolis, he excavated a small and hitherto-unknown temple situated between three known large temples; and this he associated with the pre-Socratic philosopher Empedocles (Heroon or shrine of Empedocles, 5th century BCE, but today thought to date to the 4th or early 3rd century BCE and more likely to have been dedicated to Asclepius, Greek god of medicine).

在对于考古学的热忱与好奇的驱使下,希托夫1 8 2 3年9月从巴黎出发,又于1 8 2 4年1月离开西西里,周游了意大利和希腊殖民地(他并未真正到访过希腊本土,这在那个时代是种常见的方式)。在西西里岛,尤其是在岛上的西南沿海城市阿格里真托附近,最西端的希腊殖民地赛林努特,希托夫获得了关于希腊(大希腊殖民地)建筑的一手经验13)。在当地的卫城,他在3个已知的大型神庙之间发掘了一座当时还不为人知的小型神庙。他将这座神庙与前苏格拉底时期的哲学家恩培多克勒联系起来(恩培多克勒墓祠,公元前5世纪;最近的研究倾向于将其断代为公元前4世纪或3世纪早期,且更有可能用来祭祀古希腊医神阿斯克勒庇俄斯)。

就在1824年,希托夫已经预感到他的理论——当时已经在法国专业学者的小圈子里通过书信传播开来——将会引发公众的兴趣和争议,并将他旅行的成果汇报给了巴黎美术学院(在巴黎美术学院汇报我的西西里之行的回忆,及1824年7月24日会议的摘要)[1]47。1820年代末期,希托夫开始自费发表他的学术成果。他的《现代建筑》一书在1826–1835年分18期连载出版,颇受好评;然而他的《古代建筑》原计划出版30期,却在第8期时突然中断14)。其中的原因,除了高昂的印刷成本因素外,更多是因为希托夫本人开始质疑这个计划的现实性以及法国读者们对古典建筑普遍施以彩绘这一观点的接受程度[3]170。

为了提升自己的履历、获得更多的社会认可,1830年,希托夫在巴黎美术学院和法兰西题刻与文学艺术学院展示了他在赛林努特发现的那座小神庙的复原设计图纸(整体设计成多立克式,却用了爱奥尼式的柱头)5)。

他提出了几条论点。其一,在古希腊各个时期的宗教建筑中,色彩一直是一个至关重要的因素。其二,在地中海区域丰郁的自然环境与得天独厚的光照条件下,只有色彩能够创造建筑与环境之间的和谐统一;其三,色彩运用源于实用因素(保护结构)。在早期希腊神庙中,色彩涂层原本被用来保护其木结构(不受自然环境侵蚀),后来木构件被代之以普通石材(由彩色灰泥涂层保护)和大理石(由透明蜡保护);其四,彩饰是一项早已熟练和普及的技艺,因此在古典时期并不需要在文字中加以特别说明。这也解释了为何在那些古老的文献中缺少对于彩饰法的说明;其五,用强烈的色彩组合(例如柱子用明黄为主色而三陇板用蓝色)来勾勒并强化建筑造型的方法,这并不是恩培多克勒神庙独有的现象,而是在整个古希腊世界普遍存在的现象。最终详尽成果的出版,直到1851年才得以实现16)。反响是剧烈的。

3.1.3 劳尔-罗谢特,希托夫最坚定的反对者

德西雷-劳尔·罗谢特 (1790–1854)生于法国谢尔河地区的圣阿芒蒙龙,是一位兼具智慧和雄心且非常成功的考古学家,年仅20多岁就取得了巴黎路易大帝学校(1813)和巴黎大学索邦神学院(1817)的历史教授职位[3]11。

早在1816年,罗谢特就成为了法兰西题刻与文学艺术学院的院士;三年之后的1819年,他又成为了法国国家图书馆的古物主管人,他担任这一职务直到1848年。1829年,他成为了法国国家图书馆的考古学教授——这是一个专为他设置的职位,他在这里作为演说家获得了辉煌的声誉。1839年罗谢特接任考特梅尔担任巴黎美术学院的常务部长,直到1854年辞世。他的学术成果得到了广大艺术爱好者的高度赞誉,却没有在同行学者那里获得同样高的评价。后者质疑他对当代德意志文学与科学的知识广泛而流于表面。

罗谢特比希托夫年长几岁,却是他最强劲的反对者17)。

他犀利地反驳了希托夫的观点,并对整个古典建筑彩饰理论表示了怀疑。这一立场最初形成于他的《地下墓葬中的基督教壁画》一书中,并于1830年在法兰西题刻与文学艺术学院展示,作为对希托夫的赛林努特神庙复原设计的直接回应。其后,他又在《学者报》的多篇文章,以及另外两本书(《未出版的古典绘画》,1836年;《关于希腊绘画的考古学信件》,1840年)中发表了进一步的阐述(尽管并没有多少新观点)。他针锋相对地提出:其一,公共建筑一直以来都用木板而非壁画来装饰;其二,壁画仅仅用于不太重要的建筑中;其三,它们仅在较晚和较为衰落的时期才被使用。他解释说那些墙面上的颜料痕迹都是较晚时期的添加,即中世纪绘画的残留。

3.1.4 森佩尔,站在希托夫的肩膀上,迈向彩饰建筑的相对主义美学

1834年,这场彩饰之辩突破了法兰西的国界,被一位名叫戈特弗里德·森佩尔(1803–1879)的年轻人进一步发扬光大18)[7]。森佩尔因开创性的面饰理论和为萨克森王室设计建造的歌剧院(1838–1841)而闻名。他曾在慕尼黑和巴黎(1826)求学,并曾在巴黎受到老师弗朗茨-克里斯蒂安·高乌(1790–1854)的鼓舞,因此对希托夫那富有争议的作品和古典建筑彩饰的发现探索心驰神往。

1830年法国七月革命之后,森佩尔离开了巴黎,启程前往意大利西西里和希腊。与其说森佩尔在这些地方证明了希托夫曾经证明过的内容,即建筑彩饰的存在,不如说他开始形成了一套个人的理论(作为他“面饰理论”基础的建筑美学)。1834年重返德国后,森佩尔在高乌的推荐下担任德累斯顿美术学院的建筑学教授,并以职业建筑师的身份在萨克森公国工作,直到1849年,他由于参与了德累斯顿的五月起义运动而被迫逃亡到巴黎和伦敦。

森佩尔在《古代创作的建筑与造型之初评》(1834)一书中,描绘了他的彩饰理论的初步框架(试图为彩饰法寻求一种并非局限于古典时代的普遍而抽象的原则)。他凭借这本凝练实用的小册子一举成名,随后又在《建筑与雕塑中的色彩运用》(1834-1836)和《建筑四要素》(1851)两部著作中进一步完善了这一理论。

11 意大利赛林努特的恩培多克勒神庙中出土的三陇板残片(意大利巴勒莫考古博物馆;转引自《色彩里的神》图版26)/Triglyph from the "Empedocles" (Asclepius) Temple in Selinunte, Italy (Palermo Archaeological Museum, Italy;reprint in Brinkmann, Bunte Götter, fgure 26)

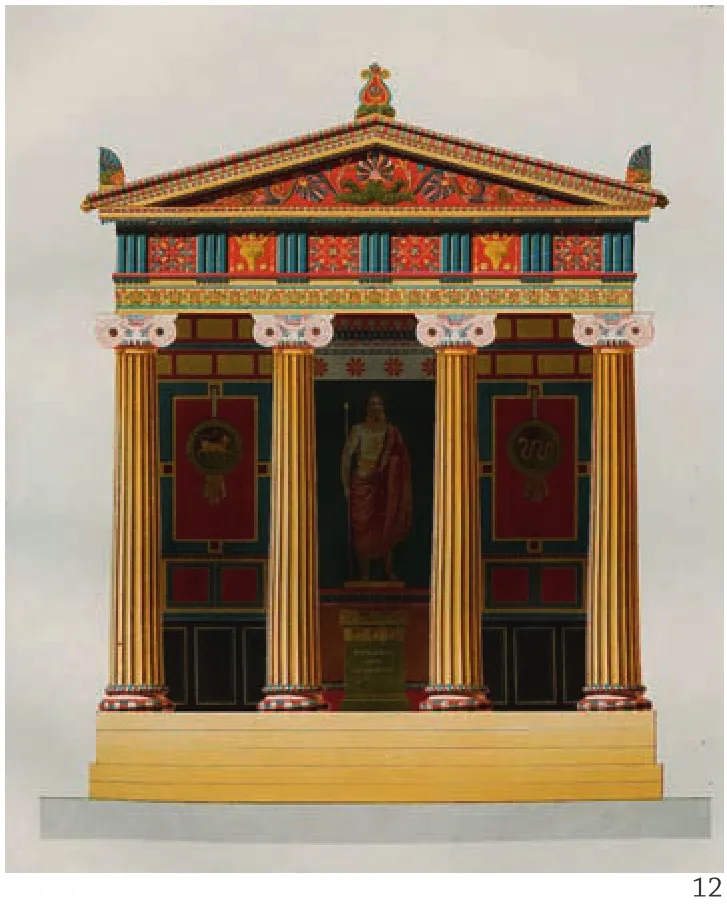

12 意大利赛林努特的恩培多克勒神庙(希托夫,《赛林努特的恩培多克勒神庙复原》,图版2)/Empedocles Temple in Selinunte, Italy (Hittorf, Restitution du temple d'Empédocle à Sélinonte, plate 2)

13 帕提农神庙西立面,希托夫的复原设计(希托夫,《赛林努特的恩培多克勒神庙复原》,图版8右侧)/West facade of the Parthenon, reconstructed by Hittorf (Hittorf,Restitution du temple d'Empédocle à Sélinonte, plate 8, right)

In the same year (1824), Hittorf, aware that his theory – already known to a small circle of French experts through his letters – would arouse public interest and controversy, reported to the Académie des Beaux-Arts (Mémoires sur mon voyage en Sicile,lu à l'Académie des Beaux-Arts de l'Institut avec l'extrait du procès-verbal de la séance du 24 juillet 1824).[1]4In the late 1820s, Hittorf began to publish his findings from his own pocket. His Architecture moderne was well received and published in 18 installments from 1826 to 1835; whereas his Architecture antique came to a sudden halt after the eighth of the 30 installments planned.14)Reasons for publication being halted included not only the high costs of printing but even more so, Hittorff's own doubts about the feasibility of such a project and the readiness of the French reader to accept the very idea of the universal polychromy of ancient buildings.[3]107

In order to raise his profle and achieve greater public recognition, in 1830, Hittorff presented at the Académie des Beaux-Arts and the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres a paper reconstruction(in the Doric order with Ionic column capitals) of the small and rather insignificant temple he had discovered in Selinunte.15)

He put forward several arguments: first, that color had been crucial to Greek religious architecture at all times; second, only colors created a setting that allowed the building to be in a harmony with its lush surrounding landscape and unique lighting in the Mediterranean region; third, the use of colors stems from practical (conservation) reasons, originally protecting the wooden components of the frst Greek temples from the elements, the components only later being made of common stone (protected by colored plaster) and marble (protected by transparent wax);fourth, polychromy was an established and common practice, which is why it had been unnecessary to specifcally address the issue in classical texts, which explains the absence of descriptions of polychromy in those texts; ffth, the color scheme in strong tones(for example, bright yellow as the basic color applied to columns; blue applied to triglyphs) which outlined and defined the contours of the building was not a phenomenon unique to the Empedocles temple, but rather a phenomenon universal to the whole of the ancient Greek world. The fnal lavish publication was delayed until 1851.16)Reactions were swift.

3.1.3 Raoul-Rochette, Hittorff's most determined opponent

Desiré-Raoul Rochette (1790-1854), born at Saint-Amand-Montrond in the department of Cher in France, was a brilliant, ambitious, and highly successful French archaeologist, obtaining in his mid-twenties a professorship in history at the College of Louis-le-Grand in Paris in 1813 and at the Sorbonne in 1817.[3]11

As early as 1816, he became a member of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-lettres, and three years later, in 1819, he became superintendent of antiquities at the National Library of France(Bibliothèque Nationale), a position which he occupied until to 1848. In 1829, he was made professor of archaeology at the National Library, a position created specifically for him, and on which he built a brilliant reputation as a speaker. From 1839 (succeeding Quatremère de Quincy) until his death in 1854, he was Perpetual Secretary of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. His scholarly works were highly esteemed by art enthusiasts, albeit rather less so by professionals, who questioned the depth of his widespread but superficial knowledge of contemporary German literature and science.

Raoul-Rochette, only a few years older than Hittorf, was his most ferce adversary.17)

He sharply rejected Hittorff's ideas and called into question the whole idea of polychromy of antique architecture. This was frst formulated in his Mémoire sur les peintures chrétiennes des catacombes and presented at the Académie des Inscriptions et Belleslettres in 1830 as an immediate response to Hittorf's Selinunte temple reconstruction, and subsequently elaborated (albeit without raising many new points),in a number of articles, published in the Journal des Savants and two books (Peintures antiques inédites,1836; Lettres archéologiques sur la peinture des Grecs,1840). He argued that frst, public buildings had been embellished with wooden panels but not with wall paintings; second, wall paintings were used only in less important architecture; and third, they were used only in a late stage and period of decline. He explained the color traces of wall plaster as later additions, i.e.remains of painting from the medieval period.

3.1.4 Semper, via/expanding on Hittorf toward a relative aesthetics of painted architecture

In 1834, the polychromy debate went beyond the borders of France and was further infamed and amplified by the young Gottfried Semper (1803-1879).18)[17]Semper, best known for his pioneering theory of wall cladding and his design for the Dresden Hoftheater (1838-1841) commissioned by the Saxon court, studied in Munich and Paris (1826),where he, encouraged by his teacher Franz Christian Gau (1790-1854), became fascinated by Hittorf's controversial work and his findings related to the polychromy of ancient buildings.

Semper left Paris in 1830 (after the July Revolution) for Italy (Sicily) and Greece, which was the starting point for his own theory (relative aesthetics of architecture as the foundation of his"cladding theory" [Bekleidungstheorie]) rather than to prove the existence of painted decoration as Hittorf had a decade earlier. After his return to Germany (1834), Semper worked as a professor of architecture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Dresden(on Gau's recommendation), and as a professional architect in the Kingdom of Saxony until 1849,when he had to fee to Paris and London because of his participation in the May Uprising.

Semper produced a preliminary outline of his theory on polychromy (searching for a general abstract principle of polychromy) in Vorläufige Bemerkungen über bemalte Architectur und Plastik bei den Alten(1834), a small booklet that provides practical and useful information and through which he made a name for himself, and elaborated it in Die Anwendung der Farben in der Architektur und Plastik (1834-36;unpublished) and Vier Elemente der Baukunst (1851).

Semper stretched the temporal boundaries of architectural polychromy, arguing that the aesthetic importance of colors in architecture was the norm for most historic buildings from antiquity to the Renaissance, when it was finally forgotten, and he gave numerous colorful examples to illustrate this.19)He praised Hittorf for his accomplishments at Selinunte, but demonstrated that darker shades of color were applied than Hittoff had originally supposed, leaving no white marble visible. He explained that the use of heavy colors was to do with the bright energy-absorbing Mediterranean sunlight(starke zehrende Licht des Südens).

To Semper, painted decoration was the later stage of a development that started with real objects hung over building parts, then painted on wall surfaces, and only then "carved into the building's mass to achieve permanence. These carvings were also painted to make them resemble the original objects they had come to replace."[4]266Semper thus synthesized Hittorf's classicist ideas of polychromy(regularity of decorative vocabulary) with "the Labroustians' belief in its origins in actual objects hung about shrines".20)[4]Semper was one of the few pioneers in the polychromy debate who suggested a visual recovery of the Parthenon in colors and his famboyant reconstruction stands in sharp contrast to Kugler's moderate approach in soft tones.[1]23,28□( To be continued )

森佩尔拓宽了建筑彩饰的界限。他提出,从古典时期到文艺复兴时期,建筑彩饰的美学价值一直在大多数历史建筑中受到强调,此后却被逐渐淡忘。他列举了大量色彩丰富的建筑实例插图来支持这一论点19)。他赞扬了希托夫在赛林努特神庙的研究中取得的成就,但他却论证了这座神庙实际上采用了比希托夫原设想更深的颜色,大理石原有的白色几乎完全被覆盖了。他解释说,深色调的运用是为了对付过于强烈的地中海阳光。

森佩尔认为,彩绘装饰是一个历史发展序列的晚期阶段:起初是由在建筑构件上悬挂物件来起到装饰的效果,接下来发展为建筑墙面彩绘,然后才是“融入建筑实体的雕刻,以达到永生不灭;而这些雕刻同样被施以彩绘,使之与他们所取代的装饰物件效果相似”[4]266。从而,森佩尔将希托夫的古典主义彩饰理论(装饰语言的规则)与拉布鲁斯特的追随者所相信的关于彩饰法起源于在圣所悬挂相关的实体物件的设想结合起来20)[4]。在彩饰之辩中,森佩尔是提出对帕提农神庙进行色彩复原的少数先锋派人物之一,而他那艳丽华美的复原成果与库格勒采用柔和色调的雅致版本形成鲜明对比[1]23,28。□(未完待续)

14 帕提农神庙东立面,森佩尔的复原图(瑞士苏黎世理工大学藏,转引自策拉姆《神祇、陵墓与学者:考古学传奇》图版2)/East facade of the Parthenon, reconstructed by Semper (Semper Archives at the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule in Zürich, Switzerland; reprint in C.W.Ceram,Götter, Gräber und Gelehrte: Roman der Archäologie, plate 2)

注释

1)18世纪的“考古学”,实际上是并非现代意义上的考古学,而是泛指一种对于古代艺术品的记录和分析。当时还未建立地质学意义上的“地层”理论,人们还相信人类起源于《圣经》所述的几千年前,现代田野考古学的基本理念与方法尚未建立。

2)温克尔曼在罗马长达11年(1755 – 1766)的逗留之中,曾到访过位于意大利南部的古希腊遗址(帕埃斯图姆)和位于坎帕尼亚的罗马庞贝古城。

3)关于温克尔曼对于彩饰雕塑和大理石白色的看法,分别参见《古代艺术史》第二版(1776)和《古代建筑研究》(1762)。(“白色能够反射出各种各样的光芒,使建筑有如白色本身一样纯净臻美。” 《古代艺术史》p147-148)。

4)在古希腊和古罗马建筑领域的地位仅次于温克尔曼的,是18世纪德国考古学家阿洛伊斯·希尔特。在1782 – 1796年间,阿洛伊斯曾久居罗马。在1798年他成为普鲁士国王古董收藏的负责人,并于1810年担任柏林大学的艺术理论史教授。(《以弗所神庙》,柏林,1809年;《古代建筑理论》,柏林,1809年)

5)年轻的法国建筑师朱利安-戴维·勒·罗伊,同时也是罗马法兰西学院的寄宿生,在1758年发表了他的雅典古建筑测绘报告。这次测绘历时不到3个月,在时间上要早于斯图尔特和雷维特。

6)帕埃斯图姆的古遗址是早期考古学的重要实例。截至1774年已有9个不同版本的图册在市面上发行。

7)这个意向性的计划在德意志艺术家、艺术收藏家和路德维希在罗马的艺术顾问马丁·冯·瓦格纳(1777–1858)于1816年12月12日写给这位巴伐利亚皇储的信中有明确的表述。

8)巴黎美术学院在1648年创立之初名为法兰西皇家雕塑绘画学院,致力于培养建筑学和装饰艺术方面的青年才俊。1793年,巴黎美术学院与让·巴蒂斯特·柯尔贝尔在1671年创建的皇家建筑学院合并,并在1863年脱离了政府的管控,更名为巴黎美术学校。自1968年起,学校不再教授建筑学,并且再次更名为巴黎国立高等美术学校。

9)在雅典民众的支持下,希腊国王奥托(1832–1862)在1843年夺取了政权,并于次年颁布了希腊的第一部宪法(1844宪法)。雅典法兰西学校创建于1846年,并且自1847年开始招收来自法国的建筑师。10)考特梅尔将术语“彩饰”定义为“多色的”,这在1878年被巴黎美术学院正式接受(范·赞特恩,建筑彩饰法,p83)。关于考特梅尔·德·坎西,参见历久弥新的《考特梅尔·德·坎西与他的艺术成就》一书。

11)来自其他“次等”文化的建筑被视为“不合规范的”。

12)希托夫的主要作品有,协和广场的(重新)设计、香榭丽舍大街沿途的众多咖啡馆和餐厅、巴黎凯旋门四周围成环状的建筑物以及布格涅森林中的许多装饰性建筑物。

13)莱奥·冯·克伦策曾在赛林努特拜访过希托夫。他在《阿格里真托的宙斯神庙》(1827)一书的第二修订版中采纳了希托夫的彩饰法观点。(克鲁夫特,《建筑理论史》,p304)

14)每一篇连载都由6幅插图以及一段简要的说明性文字组成。文字部分谨慎地指出了多座古建筑上存在的颜色痕迹,却并没有大肆推广他的系统而丰富的建筑彩饰理论。

15)《希腊建筑彩饰记录》,巴黎,1830年。同年发表于学院年报(《希腊的建筑彩饰—赛林努特的恩培多克勒神庙的完整复原》)。

16)那时,一种名为彩色平板印刷术的新技术开始流行,并取代了成本较高且费时费力的传统手工印刷方法。这种新技术能够满足大批量且高质量的彩色印刷需求。

17)罗谢特的观点在希托夫1851年的《赛林努特的恩培多克勒神庙复原》中得以总结。

18)关于森佩尔的美学理论,参考海因茨·奎特兹克《戈特弗里德·森佩尔的美学观点》。

19)森佩尔在罗马最负盛名的图拉真柱(建造于113年)上发现了尚未被注意到的颜色痕迹。这促使他将自己的彩饰理论拓宽到古希腊文化之外的领域。(森佩尔,《论文集》,p107)

20)克鲁夫特指出森佩尔抨击了克伦策对历史风格的模仿(《建筑理论史》,p311)

[1] 范·赞特恩. 1830年代的建筑彩饰法. 纽约:加兰出版社,1977.

[2] 温岑茨·布里克曼和安德烈亚斯·舒尔 编. 色彩里的神——古典雕塑的彩饰. 慕尼黑. 希尔默出版社,2010.

[3] 卡尔·哈默. 雅各布·伊格纳茨·希托夫. 斯图加特:安东·希尔泽曼出版社,1968.

[4] 戴维·范·赞特恩. 帕提农神庙的彩饰// 帕提农神庙及其对现代的影响. 帕纳约蒂斯·图尼基沃蒂斯编. 雅典:梅丽莎出版社,1994.

[5] 汉诺-沃尔特·克鲁夫特. 建筑理论史:从维特鲁威到现在. 罗纳德·泰勒英译. 纽约:普林斯顿建筑出版社.1996. 王贵祥译. 北京:中国建筑工业出版社,2005.[6] 富特文勒. 埃伊纳:阿法雅圣地.

[7] 海因茨·奎特兹克. 戈特弗里德·森佩尔的美学观点. 柏林:学术出版社,1962.

[8] 弗朗兹·库格勒. 关于希腊建筑和雕塑的彩饰及其局限性. 柏林. 1835.

[9] 詹姆斯·弗格森. 印度及东方建筑史. 建筑历史第1版第4卷. 伦敦. 1876. 赫尔施修订第3版第3卷. 伦敦. 1899.

[10] 詹姆斯·弗格森. 各国建筑通史:从远古到现代.伦敦. 1865-67. 赫尔施修订第3版第1卷. 伦敦. 1893.

Notes

1) The "archaeology" of the 18th century was still not archaeology in the strict sense. Rather, it was antiquarianism, treasure collecting, and a documentation and analysis of ancient artworks. Neither were the principles of uniformitarian stratigraphy discovered nor the basic concepts of modern field archaeology. People time still upheld the biblical view of the origin of humans.

2) Winckelmann visited southern Italian ruins of the ancient Greek (Paestum) and Roman (Pompeji)empires in Campania region during his decade-long stay in Rome (1755-66).

3) On Winckelmann's ideas on polychrome statues and on white color see his Anmerkungen über die Baukunst der Alten, 1762, and his second edition of Geschichte der Kunst der Altertums, 1776. ("Da nun die weiße Farbe diejenige ist, welche die mehresten Lichtstrahlen zurückschicket,…so wird auch ein schöner Körper desto schöner sein, je weißer er ist." [Geschichte der Kunst der Altertums, 147-48])

4) Another 18th-century German archaeologist for ancient Greek and Roman architecture next to Winckelmann was Aloys Hirt (1759-1837), who after his 1782-96 stay in Rome became responsible for the King of Prussia's antiquities collection (from 1798) and professor of art history and theory at the University of Berlin (from 1810).(Der Tempel der Diana zu Ephesus. Berlin: 1809. Die Baukunst nach den Grundsätzen der Alten. Berlin: 1809.)

5) Julien-David Le Roy (1724-1803), a young French architect and pensionnaire at the French Academy in Rome (Académie de France à Rome) published his survey of the Athens monuments, measured in less than three months, even before Stuart and Revett (Les Ruines des plus beaux monuments de la Grèce, 1758).

6) The ruins of Paestum were key for early archaeology,with nine diferent illustrated print publications by 1774.

7) As evident in a letter to the Bavarian crown prince Ludwig from December 12, 1816 written by Martin von Wagner (1777-1858), a German artist, art collector and Ludwig's art agent in Rome.

8) Founded as the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in 1648 to educate talented students in building and decoration, the Académie des Beaux-Arts merged in 1793 with the Académie Royale d'Architecture (founded by Jean-Baptiste Colbert in 1671). In 1863, the school became independent form the government, changing its name to École des Beaux-Arts. Since 1968, architecture is no longer taught there, and the school was renamed as École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts.

9) After the military garrison of Athens, with the help of citizens, rebelled in 1843, King Otto of Greece (r. 1832-62)released the first constitution of the Kingdom of Greece(1844 Constitution). The École française d'Athènes (French School at Athens) was established in 1846, and since 1847,it was open to French architects.

10) Quatremère de Quincy coined the term polychromie (polychromy) meaning "many-colored"that was officially accepted by the Academie des Beaux-Arts in 1878 (Van Zanten, The Architectural Polychromy, 83). For Quatremère de Quincy see the old but still up to date work by Schneider, Quatremère de Quincy et son intervention dans les arts.

11) The architecture of other "weaker" cultures was regarded as "irregular".

12) Hittorff (re)designed the Place de la Concorde(1833-46) in Paris, many cafés and restaurants of the Champs Elysées, the houses forming the circle round the Arc de Triomphe de l'Étoile, and many embellishments of the Bois de Boulogne.

13) Leo von Klenze who visited Hittorf at Selinunte adopted Hittorf's view on polychromy in the second revised edition of his Der Tempel des Olympsischen Jupiter von Agrigent (1827). Kruft, A History of Architectural Theory, 304.

14) Each installment consisted of six plates and a short explanatory text that pointed out color traces at various buildings in a cautious form, not yet/without propagating his all-encompassing system of architectural polychromy that should have been included in the text volume presented at the end/last part.

15) "Mémoire sur l'architecture polychrome chez les Grecs, Paris 1830" and published in the Académie's annals in the same year ("De l'architecture polychrôme chez les Grecs, ou restitution complète du temple d'Empédocle dans l'acropole de Sélinonte").

16) By then, a new and more advanced method of printing illustrations in multiple colors at high numbers and good quality known as chromolithography had become popular and replaced the traditional cost- and time-intensive hand-coloring.

17) Raoul-Rochette's arguments are summarized in Hittorff's Restitution du temple d'Empédocle à Sélinonte (1851).

18) For Semper's aesthetic theories see for example,Quitzsch, Die ästhetischen Anschauungen Gottfried Sempers.

19) Semper discovered hitherto unnoticed traces of color at one of the most prestigious monuments in Rome, the Trajan's column (built 113), which led him to expand his theory of polychromy beyond the boundaries of ancient Greek culture. Semper, Kleine Schriften, 107.20) Kruft points out that Semper attacked Klenze's imitation of historical styles (A History of ArchitecturalTheory, 311.).

[1] van Zanten, David. The Architectural Polychromy of the 1830's. New York: Garland, 1977.

[2] Brinkmann, Vinzenz and Andreas Scholl (Eds).Bunte Götter. Die Farbigkeit antiker Skulptur. Munich:Hirmer, 2010.

[3] Hammer, Karl. Jakob Ignaz Hittorff. Ein Pariser Baumeister, 1792–1867. Stuttgart: Anton Hiersemann,1968.

[4] van Zanten, David. "The painted decoration of the Parthenon". In The Parthenon and its Impact in Modern Times, edited by Panayotis Tournikiotis. Athens: Melissa Press, 1994.

[5] Kruft, Hanno-Walter. A History of Architectural Theory: From Vitruvius to the Present. Translated by Ronald Taylor. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996. Translated by Wang Guixiang. Beijing:Zhongguo jianzhu gongye chubanshe, 2005.

[6] Furtwängler, Adolf (1853-1907) et al. Aegina: Das Heiligtum der Aphaia. Academy of Sciences: Munich, 1906.

[7] Quitzsch, Heinz. Die ästhetischen Anschauungen Gottfried Sempers. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1962.

[8] Kugler, Franz. Über die Polychromie der griechischen Architektur und Skulptur und ihre Grenzen. Berlin: 1835.

[9] Fergusson James. History of Indian and Eastern Architecture. 1st ed. Vol. 4 of A History of Architecture.London: 1876. Here, rev. 3rd ed. Vol. 3. London: 1899.

[10] Fergusson, James (1808-86). A History of Architecture in all Countries from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. London: 1865–67. Here, rev. 3rd ed.Vol. 1. London: 1893.

Repainting Antiquity: The 19th-Century Architectural Polychromy Debate SeenThrough "German" Eyes: Hittorf, Semper, Kugler and Their Generation (1)

The paper investigates the 19th-century dispute over polychromy that revolutionized contemporary understandings of antiquity, especially ancient Greek and Roman temple structures. The Prussian, Bavarian, and German-born French architects discussed in this paper played a key role in this process, despite “Germany” as a nation only becoming a driving force in the formulation of architectural theory at a relatively later stage. The paper places the debate within the larger context of the time,subsequently analyzing conflicting theories regarding the highly disputed but undeniable fact of polychromatic classical architecture. This re-visioning of the debate surrounding polychromy of antiquity will serve to improve our understanding of modern Greek revival architecture and even more so, our understanding of Western historiography on Chinese architecture.

19th-century European polychromy dispute,ancient Greek architecture, colors, Aphaia Temple,Parthenon, Ignaz Hittorf, Gottfried Semper, Franz Kugler,Johann Joachim Winckelmann, James Fergusson

清华大学建筑学院

2017-08-18