高处的风景

2016-06-08子昊

子昊

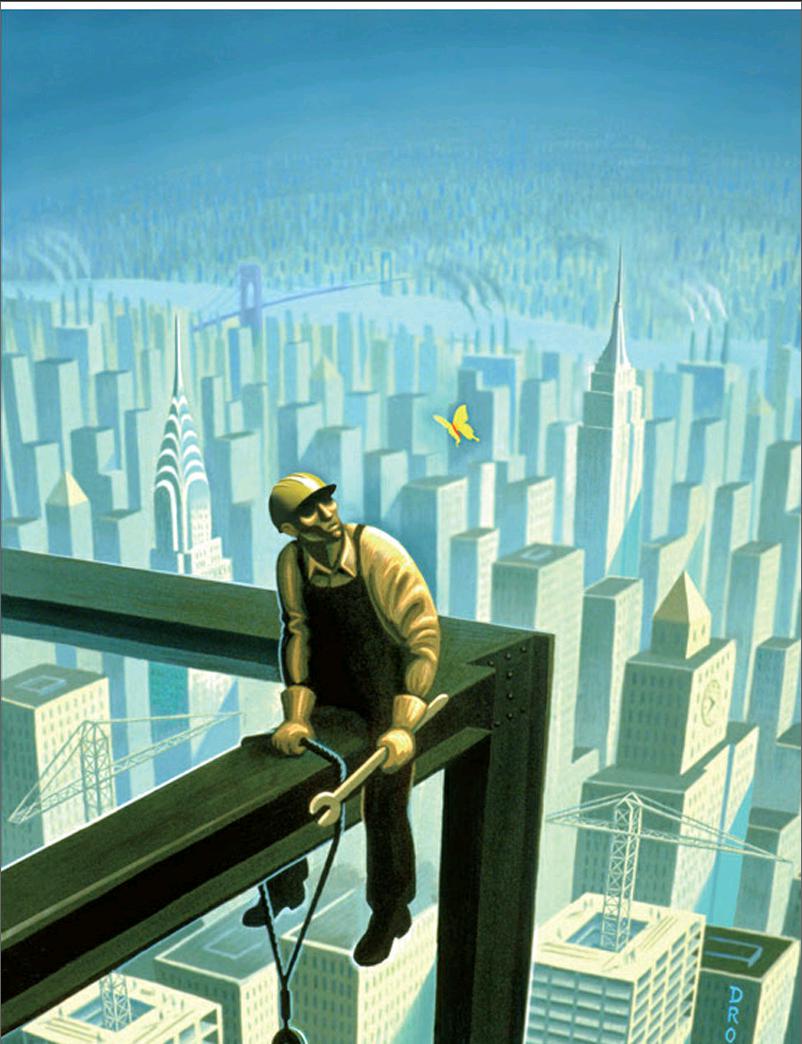

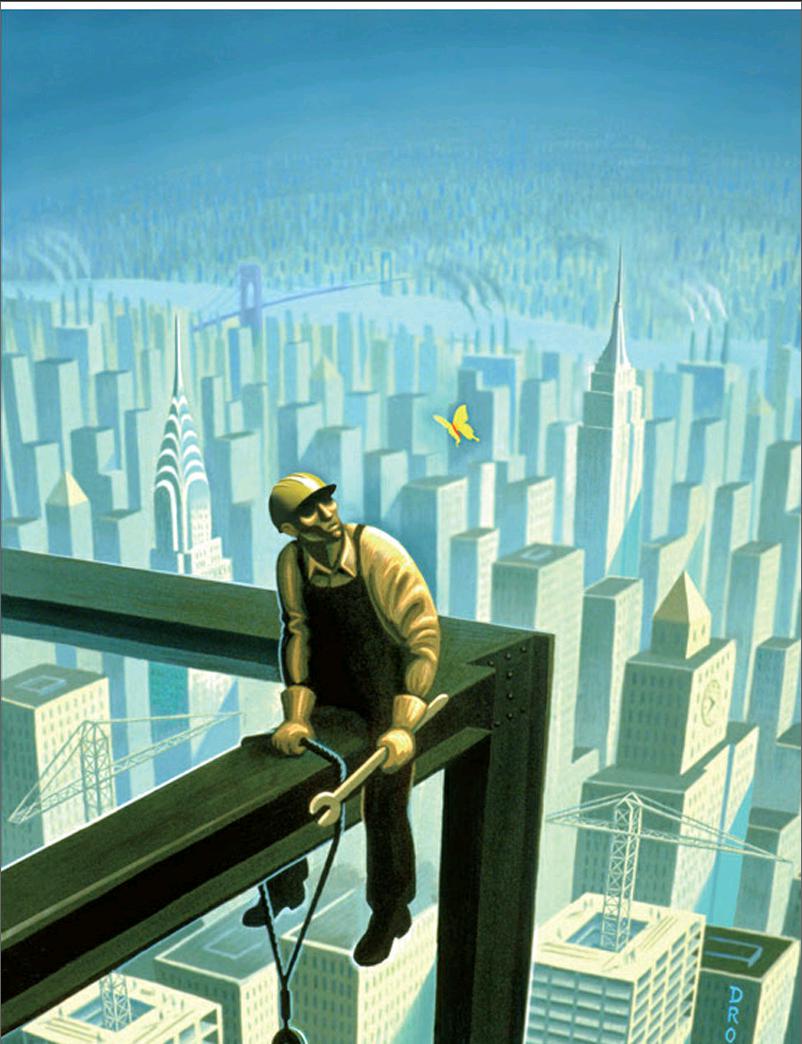

In 2009, the New Yorker featured Eric Drookers drawing “The Iron Worker & The Stranger” on its cover. The image depicts a WPA1)-style lone beam-rat2)straddling an I-beam on an incomplete building rising so high above the rest of Manhattan. The iron worker looks more bronze sculpture than man, not caught in the hurried pace of construction, but lost in a moment, gazing up at a yellow butterfly that somehow has found its way to the top of the metropolis on the trade-winds of New York City.

My cubicle is near a window overlooking those same lower Manhattan canyons. Twenty-eight stories up: the highest Ive ever been in a building in my life. I keep Drookers cover in a frame in the corner of my window. Had my ancestors lived in New York, its possible they would have ascended this high, if not higher, on the Manhattan skyline—but they would have done it in Levis3) and steel-toed boots, not Florsheims4) and a suit.

Im waiting on our corporate travel agent to let me know whether hes going to have my passport finalized5) by the end of the day. At the last minute, the passport office sent me a letter requesting additional documentation to prove that I am who I say I am. Still, I stare at that painting in my window, and my passport seems like that butterfly: Its probably within grasp, but it could, at any moment, drift out of view, leaving me with nothing to do but get back to work.

The notion of upward mobility is something slippery6), something I dont understand. Yet its also something tangible. Things change as you ascend. You start removing words from your vocabulary and incorporating new ones. You walk differently. When you go to the airport, you no longer have to listen to what the TSA7) agent is saying at the security gate. Youve been there. Youve done that.

The things you need to carry in your wallet start to change. I realized this just yesterday while rifling through my own wallet. My union card, my student ID, a health insurance card under my mothers plan: When I took my new job, I took them out. Now theyre in a box somewhere, no longer necessary extensions of my identity, but tokens of my past lives.

Whats replaced them? My building access card, my own health-insurance card, a dozen receipts that I need to itemize and submit for reimbursement8), and 600 U.A.E. dirhams9) for the trip I may or may not be taking on Saturday.

But these changes are all superficial. I still make less money than either of my parents. I still struggle to cover my bills and pursue my artistic ambitions. I still have to call my mother when things are hard and I dont know what to do. So what part of me is upwardly mobile? To where am I ascending?

I have a friend who, like me, was raised by a single mother. But his upbringing, until he moved to Ventura, Calif., and transferred to my high school, was more metropolitan than mine. And while my mother only had a high school education (and my father, even less than that), our families struggled to raise their children in very different ways. My mother worked two jobs to make enough money to pay the rent; his mother struggled as she tried to raise two kids while attending graduate school and starting out as a professor. My friend tries to explain to people that while he knows what its like to belong to a lower economic class, hes never known what its like to belong to a lower social class.

This is not to discount his struggles, or his mothers successes. And my mothers success was measured in the fact that she raised five children on her own. But a professor of mine once illustrated the difference between the worlds in which mine and my friends mother struggled when he told our class, “As a student of the liberal arts, a lot of what youre learning is just stuff for you to say at cocktail parties.”

When he said that, a lot of people in the classroom scoffed. But then, a lot of those people had grown up in homes where their parents hosted cocktail parties, parties to which the children might have been invited, asked to wear little suits or polo shirts or dresses to match their mothers, and recited poems in front of the group. In college, a lot of these students were performing dry runs10) as young socialites11) in their dorm rooms with boxed wine andjoints12), talking about obscure pop music, professorial scandals, and Jacques Derrida13).

No one in my family knows who Derrida is. When my mom or dad had company over, they would drink Coronas and pre-mixed margaritas14) and ask me to take out the guitar and sing Cocaine Blues and Friends in Low Places.

I sincerely believe that both of these types of upbringing have value, though I wouldnt trade mine for any other. But it leaves me in a strange place on this path of upward mobility. Every time I call home, the gap has increased between my sisters experiences and my own. We read different news, watch different television shows, not because of intelligence but circumstance. We have come to know the world in a different way.

My younger sister called me, after she heard about my trip, and said, “Bubba, I heard youre moving to Africa.” After I told her where Abu Dhabi was, she explained to me that a relative had told her that I was moving to Africa and would be taking a job as a reporter in Palestine. I told her that I wished my life were that exciting.

And that story is not a dig on my sister. At 22, she spends her time dealing with the complications that come with raising two daughters who have no father around to speak of. It makes no difference to her where Abu Dhabi is. The exact geographical coordinates15) of the Palestinian territories dont matter. But what does matter to her is where I am. And I get to be this portal16) to the world for my family and friends back home. I get to send them pictures from the places Ive been, and to tell them stories from places outside Ventura. And I think what matters most to me is that my nieces and nephews (I have something around 10 of them) can see me as one person in the family who did something a little different, and see in me another model for life, in addition to the hard-working, blue-collar examples they have back home.

What I dont tell them is that I often feel as distant from the people here in New York as I do from them. The friend I mentioned earlier came to New York to visit me for a weekend. We went for a walk on the promenade17) in Brooklyn Heights, where you can look out on the Manhattan skyline. It was night, and the buildings were lit up in that miraculous way that almost makes up for the fact that you cant see a single goddamn star any more. We both thought it was beautiful, but when I asked my friend which building was his favorite, he said, “Its just a bunch of corporate phalluses to me.”

I couldnt figure out why his comment bothered me. But then something clicked. When we both looked at the skyline, he was thinking about the people who lived and worked in those multi-million-dollar condos and offices, while I was thinking about the people who built them. I imagined the past and present men who risked their lives every day to feed their families. The Irish and the Italian and the Mohawks18) and the Puerto Ricans and the man on the New Yorker cover: everyone who climbed, day after day, higher and higher, to create the skyline that now dwarfs the image of Lazaruss “New Colossus19).”

That poem was written when the tired, poor, huddled masses came to America by boat, and they looked up at the Statue of Liberty as an ideal: grandiose20)in its scale but human in its depiction. Now the vast majority of immigrants from overseas fly into the United States with passports that they often had to go through immense hurdles to get. As I wait for mine, I can walk to one end of my office and look out at One World Trade Center, and on the other side I can see the ferry that shuttles people from Manhattan to Staten Island21). It floats past the Statue of Liberty, a green toy, distant and beneath me.

The travel agent comes through the door and hands me my passport. I call my mother to let her know that Ill be making the trip. I try to hide that Im choked up.

通过努力打拼,我从小地方来到纽约这座大都市扎根,经济条件好转,社会地位有所提升。但“人往高处走”带来的变化却让我处于一种尴尬的境地:环境的差异让我的生活和思想与故乡的亲人们渐行渐远,而受童年成长经历影响的我终究也不能像土生土长的大都市人那样看待周遭的一切……

Good Reading

2009年,一期《纽约客》杂志使用了画家埃里克·德鲁克名为《钢结构安装工人和陌生人》的画作作为封面。这幅画描绘了一个与公共事业振兴署的宣传画风格相似的建筑工人正孤零零地跨坐在一座在建高楼的工字梁上。这座楼高耸入云,俯瞰曼哈顿的其他建筑。那个建筑工人看起来不像是人,更像是一尊青铜塑像,画中的他不是在匆忙地施工,而是一时出神地凝视着一只不知怎么借着吹过纽约的信风飞到了城市之巅的黄色蝴蝶。

我办公的小隔间挨着窗,可以俯瞰与画中相同的下曼哈顿如峡谷般的街道。28层——这是我这辈子待过的最高楼层。我把德鲁克画的封面装在相框里,摆在窗台的一角。如果我的先辈生活在纽约,他们可能也会登上如此的高度——如果不是更高的话——到达曼哈顿的天际线,不过他们上来时穿的是李维斯工装裤和钢头靴,而不是西装革履。

我正在等待公司的旅行社代理人给我消息,确定是否能在下班前把我的护照办好。直到最后关头,护照管理处才来信要求我提供额外的文件以证明“我就是我声称的我”。此刻,我凝视着窗台上的那幅画,我的护照就仿如那只蝴蝶:它也许唾手可得,但也可能随时从眼前溜走,让我除了回去工作外别无他法。

“地位上升”是种不易把握的概念,我并不理解。但它同时又是能切实感知得到的。当你的社会地位提升,很多事会发生变化。你开始从日常词汇中去掉某些词,同时加进新词。你走路的姿势会不一样。去机场时,你不必再在安检口听美国运输安全管理局的人所说的话。你见识过、经历过了。

你的钱包里需要装的东西开始改变。我是在昨天翻看自己的钱包时才意识到这一点的。会员卡、学生证、登记在我母亲名下的健康保险卡——我找到新工作后把这些东西全都拿了出来。如今它们放在一只盒子里,不知被塞到哪儿去了。它们不再是我身份的必要延伸,而只代表我过去的生活。

取而代之的是什么呢?我所住大楼的门禁卡、我自己名下的健康保险卡、我需要逐项填报并提交报销的一打收据,以及600阿联酋迪拉姆。这些外币是为周六这趟可能走得成也可能走不成的旅行而准备的。

但这些都是表面上的变化。我依然比父母挣得都要少。我依然在费劲地支付自己的开支,追逐自己的艺术梦想。每当遇到困难,不知该如何是好时,我依然得打电话向母亲求助。所以说,我在哪方面向上提升了呢?又在升往何处呢?

我有个朋友跟我一样,也是由单身母亲抚养长大的。但相对于我的成长环境,他在搬到加州文图拉并转到我就读的高中之前,是在大都市环境里长大的。我们两人所在的家庭都艰难地养育子女,但由于我母亲只有高中学历(我父亲的学历比这还低),两家的养育方式极为不同。我母亲做两份工作,以赚足够的钱支付房租;他的母亲也竭尽全力,因为她要一边读研究生,开始教授生涯,一边还要努力抚养两个孩子。我的朋友试图向别人解释,虽然他知道经济困难是什么滋味,却从未尝过生活在社会底层的滋味。

这不是要贬低他的努力或者他母亲的成就。我母亲的成就在于她独自拉扯大了五个孩子。但是我的一位教授在课堂上的一句话点出了我母亲和我朋友的母亲分别奋斗的两个世界的区别,他说:“作为文科生,你们现在所学的很多东西只是供你们在鸡尾酒会上当做谈资罢了。”

当他说这番话的时候,教室里很多人都对此嗤之以鼻。然而,他们中的很多人正是在这样的家庭长大,他们的父母会举办鸡尾酒会,孩子们可能会收到邀请,被要求穿着与母亲的着装相配的小西装、马球衫或小礼服,在众人面前背诵诗歌。在大学里,很多这样的学生在宿舍里演练如何做一个年轻的社交名流,他们一边喝着盒装葡萄酒,抽着大麻烟卷,一边谈论着鲜有人知的流行音乐、教授们的丑闻和雅克·德里达。

我家里没有一个人知道德里达是谁。父母有客人来时,他们会喝科罗娜啤酒和预先调好的玛格丽塔鸡尾酒,还会叫我拿出吉他弹唱《可卡因蓝调》和《底层的朋友》。

我真心相信这两种成长背景各有其价值,虽然我不会拿自己的成长经历跟任何人交换。然而,在这条地位上升的道路上,它将我置于一个尴尬的境地。每次我给家里打电话,都发现我和我的姐妹们在生活经历方面的差距在拉大。我们读不同的新闻,看不同的电视节目。这并非源于智商的差距,而是环境的差异。我们对世界的认知已变得不同。

在听说我要出国旅行后,妹妹给我打电话说:“老兄,听说你要去非洲了啊。”当我告诉她阿布扎比在哪儿之后,她解释说,有一个亲戚告诉她我要搬去非洲,还会在巴勒斯坦从事记者工作。我回答她说,但愿我的生活能有那么精彩。

画作(钢结构安装工人和陌生人)

讲这件事不是要挖苦我妹妹。22岁的她要养育两个女儿,孩子的父亲又不在身边,应对这些生活上的难处就占满了她的时间。阿布扎比位于哪里对她来说没有任何意义。巴勒斯坦领土的确切地理坐标对她而言也无关紧要。但是与她密切相关的是我在哪儿。我成了故乡的家人和朋友通往世界的一个窗口。我给他们寄我去过的地方的照片,给他们讲文图拉以外的地方的故事。我想对我而言最重要的是,我的外甥、外甥女们(我大约有10个外甥、外甥女)可以看到家里有我这样一个人做着和其他人不太一样的事,可以从我身上看到另一种生活模式,而不仅仅是他们在故乡见到的勤奋工作的蓝领生活。

我没有告诉他们的是,我常常感到自己与纽约人有疏离感,就像和他们有疏离感一样。前面我提到的那个朋友有一次周末来纽约看我。我们去了布鲁克林高地的海滨步道散步,从那里可以看到曼哈顿的天际线。当时是晚上,一座座高楼大厦亮起了璀璨华灯,令人感到不可思议,几乎能够弥补天上再也看不到一颗星星的遗憾。我们都觉得那景色很美,但是当我问朋友最喜欢哪座大厦时,他回答说:“在我眼里,这不过是一堆公司的阳具而已。”

我不明白他的这个评论为什么会让我耿耿于怀,但后来我突然想明白了。当我们一起凝望天际线时,他想到的是在那些价值数百万美元的公寓和办公室里生活和工作的人,而我想到的是建造它们的人。我想到了以前和现在那些每天冒着生命危险挣钱养家的人。那些爱尔兰人、意大利人、莫霍克印第安人、波多黎各人以及《纽约客》杂志封面上的那个人:每一个日复一日、越爬越高、建造起令拉扎勒斯的诗歌《新的巨像》中的形象都相形见绌的天际线的人。

那首诗的创作时间正值那些疲惫、穷困的人们拥挤着坐船来到美国时,他们将自由女神像视作理想的象征:规模宏伟庄严,但形象饱含人的温情。如今,大多数来自海外的移民都飞往美国,为了得到所持的护照往往要费尽周折。在等我的护照时,我可以走到办公室的一侧,向外眺望新世贸中心一号楼。而从办公室的另一侧,我可以看到往返于曼哈顿和斯塔腾岛之间的渡轮。渡轮驶过自由女神像,那雕像好似一件绿色的玩具,立在我脚下很远的地方。

旅行社代理人从门外进来,把我的护照递给我。我打电话告诉母亲,我这次旅行可以成行了。我强忍着,不让她听出我在哽咽。

1. WPA:公共事业振兴署(Works Progress Administration),经济大萧条时期美国前总统罗斯福实施新政时建立的一个政府机构(1935~1943),是兴办救济和公共工程的政府机构之一。

2. beam-rat:指常在高空作业的建筑工人。

3. Levis:李维斯,著名的牛仔裤与时装品牌,始建于1873年。

4. Florsheim:富乐绅,闻名全球的正装皮鞋高端品牌,始建于1892年。

5. finalize [?fa?n?la?z] vt. 完成,最后定下

6. slippery [?sl?p?ri] adj. 模棱两可的,模糊的

7. TSA:美国运输安全管理局(Transportation Security Administration)

8. reimbursement [?ri??m?b??(r)sm?nt] n. 偿还,赔偿

9. U.A.E. dirham:阿联酋(The United Arab Emirates)的货币单位迪拉姆

10. dry run:演习,排练

11. socialite [?s????la?t] n. 社交界名人

12. joint [d???nt] n. 〈口〉大麻烟卷

13. Jacques Derrida:雅克·德里达(1930~2004),20世纪下半期最重要的法国思想家与哲学家,西方解构主义的代表人物

14. margarita [?mɑ?(r)ɡ??ri?t?] n. (由墨西哥龙舌兰酒、酸橙或柠檬汁以及橙味酒混合调制而成的)玛格丽塔酒

15. coordinate [k?????(r)d?n?t] n. 〈地〉坐标,坐标值

16. portal [?p??(r)t(?)l] n. 〈喻〉门,入口

17. promenade [?pr?m??nɑ?d] n. 海滨人行道

18. Mohawk:莫霍克人(居住在美国纽约州和加拿大的北美印第安人)

19. New Colossus:《新的巨像》,由犹太诗人艾玛·拉扎勒斯(Emma Lazarus, 1849~1903)于1883年为自由女神像而写的诗作,该诗被认为是美国自由精神的象征。

20. grandiose [?ɡr?ndi??s] adj. 庄严的,壮观的

21. Staten Island:斯塔腾岛,美国纽约市的一个岛屿与自治区,位于曼哈顿以南的纽约港内。