Cross-sectional evaluation of the adequacy of guardianship by family members of community-residing persons with mental disorders in Changning District, Shanghai

2015-12-09QiongtingZHANGHaoCHENKangJUXinNIULanjunSONGJiaCHUI

Qiongting ZHANG*, Hao CHEN, Kang JU, Xin NIU, Lanjun SONG, Jia CHUI

•Original research article•

Cross-sectional evaluation of the adequacy of guardianship by family members of community-residing persons with mental disorders in Changning District, Shanghai

Qiongting ZHANG*, Hao CHEN, Kang JU, Xin NIU, Lanjun SONG, Jia CHUI

psychiatric patients; guardianship; community care; mental health law; China

1. Background

Mental disorders have high relapse rates and pose a substantial burden to families and society.[1,2]In 2010,mental and substance use disorders accounted for nearly a quarter of the overall loss of healthy life years measured by Years Living with Disability (YLDs).[3]Many psychiatric illnesses are chronic, so in addition to effective treatments for acute symptoms, the long-term care and monitoring of patients is essential to ensure their adherence to medications and to facilitate the rehabilitation process. In China, where family members are the primary care givers for the vast majority of psychiatric patients, the signi ficance of adequate family support has been widely discussed.[4,5,6]Poor care and supervision of persons with serious mental disorders has been associated with higher levels of disability.[7,8,9]

With the rapid economic development in China and a corresponding decrease in mortality from infectious conditions, chronic illness - including mental disorders- have become increasingly important components of overall health. The first regional mental health law in China - the Shanghai Mental Health Regulations[10]- came into effect on April 7, 2002. Eleven years later,on May 1, 2013, China’s first national mental health law[11]came into effect. The promulgation of these two laws are signi ficant milestones in the protection of the rights of persons with mental disorders in China; they guarantee their right to treatment and rehabilitation.Both laws described the designation and roles of legal guardians of mentally ill persons who have limited civil capacity, and list the specific responsibilities of legal guardians when the ill person is not hospitalized.However, the new national law differs in some respects from the earlier regional regulations that were promulgated in Shanghai and some other parts of the country before the national law was passed. One of these differences is related to guardianship. The Shanghai Mental Health Regulations speci fied that the designation of guardianship should follow the General Principles of Civil Law of the People’s Republic of China,[12]which designates the spouse as the first choice,followed by parents, adult children, any other close relatives, and other relatives or friends approved by the local neighborhood or village committee. In contrast,the China Mental Health Law speci fies that anyone with full civil capacity from any one of the above categories is equally eligible to be a guardian.

Based on the 2002 Shanghai Mental Health Regulations, a community mental health service system was established that gave a signi ficant role to the legal guardians of non-institutionalized persons with mental disorders.[13]As part of this initiative, the Shanghai Information Management System of Mental Health collects medical records of all patients diagnosed with severe mental disorders at the city-level psychiatric hospital or at one of the 19 district-level psychiatric hospitals. This registry is managed by the Shanghai Mental Health Center (the single city-level psychiatric center). Every patient living in Shanghai diagnosed at one of the psychiatric hospitals with a ‘severe’ mental disorder (including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder,delusional disorder, schizoaffective disorder, epilepsyinduced mental disorder, and mental retardation with associated mental disorder) is visited by a community doctor or a neighborhood committee administrator and asked for their informed consent to be registered in this system. Once registered, the patient will receive regular home visits from community doctors, free medications, and a monthly family allowance. During the initial visit, one legal guardian is identi fied for each patient based on the prioritization of relationships with the patient described above (i.e., spouse, parent, adult children, other close relative, friend). Upon agreement,the legal guardian and the neighborhood committee sign a formal Guardianship Agreement. As stipulated in the Shanghai law,[10]the guardian’s duties include: (a)closely monitoring the person to prevent them from harming themselves, others or the public; (b) following medical advice and helping the ill individual receive out-patient or in-patient treatment; and (c) helping the individual receive rehabilitative treatment and professional skills training so they can return to society.The guardian has the legal right to request help from medical professionals and public security departments.Additional responsibilities of guardianship specified in the national law[11]include supervising the patient’s medication and helping the individual practice life skills and social skills.

As the pioneer in implementing mental health legislation in China, Shanghai has developed a model that may be useful in other regions of the country(and, possibly in other middle-income countries).However, the effectiveness of this guardianshipbased community management system has not been formally evaluated. The current study uses data from Changning District to evaluate the implementation of guardianship procedures among community-dwelling persons with mental illnesses. The aim of the study is to assess the degree of compliance with the guardianship responsibilities stipulated in the China Mental Health Law.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

The enrolment of the study participants is shown in Figure 1. Information about patients with mental illnesses was accessed through the Shanghai Information Management System of Mental Health. All registeredpatients were diagnosed by psychiatrists and visited by doctors from the community health centers. The primary diagnoses were coded according to the third edition ofChinese Classification of Mental Disorders and Diagnostic Criteria(CCMD-3).[14]At the time of the study (June 30, 2013), 4283 registered patients were living in Changning District, which has a total population was 693,750 residents. The primary diagnoses were categorized into four groups: schizophrenia (n=2613),affective disorders (n=244), developmental disability(n=969), and other diagnoses (n=457) (which included substance abuse, neurosis, hysteria, stress related disorders, obsessive and compulsive disorders).All these patients were visited at their homes by a local community health doctor and a neighborhood committee administrator from July 1 to July 31, 2013.As shown in Figure 1, 4034 guardians (one guardian for each patient) signed informed consent and completed the survey.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the study

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Changning District Mental Health Center.

2.2 Measures

A total of 42 doctors from community health centers and 179 mental health personnel from neighborhood committees were trained by psychiatrists from the Changning District Mental Health Center following standardized protocols. Each household was visited by a team of two interviewers and each team was supervised by a quality control staff member from the Changning District Mental Health Center. The interviewing teams were also responsible for regular home visits and providing community-based services, so they were acquainted with most of the targeted households. The survey forms were filled out by the interviewers after structured interviews.

The form includes three sections: (a) basic information about the patient including name, sex, age,primary diagnosis, current status of the illness, and their adherence to medications; (b) sociodemographic information of the respondent (guardian), including name, age, level of education, their relationship with the patient, and whether or not they live in the same household as the patient; and (c)the interviewers’judgment about whether or not the guardianship responsibilities are being ful filled, about the guardian’s attitude towards treatment, and (if the guardianship role is not adequately performed) the main reasons for inadequate guardianship. The inter-rater reliability of the judgment of the adequacy of guardianship among the 221 evaluators who independently evaluated three standardized cases at the end of the training was satisfactory (ICC=0.74).

The interviewers used structured questions to assess the extent to which the guardians meet the following criteria speci fied for guardians in the Chinese Mental Health Law.

(a) Receive training: whether or not the guardian attended educational training sessions at least twice a year. Two forms of training are considered: attendance at annual training sessions provided by psychiatrists at the local district or sub-district level or attendance at the quarterly mental health literacy courses provided by the neighborhood committee.

(b) Assist in treatment: whether or not the guardian accompanied the patient to their regular medical visits and physical exams and supervised the patient in taking prescribed medication on time every day.

(c) Daily life care: whether or not the guardian took care of the patient’s daily life needs when the patient was not able to live independently.

(d) Provide psychological support: whether or not the guardian provided support when the patient had emotional outbursts.

(e) Rehabilitation: whether or not the guardian cooperated with the doctor in providing rehabilitative treatment when needed.

(f) Monitoring: whether or not the guardian reported to the neighborhood committee and contacted psychiatrists when the patient’s condition became unstable or when the patient needed any form of emergency care.

After asking questions about these criteria, the interviewers determined whether or not the guardian was adequately fulfilling the expectations and, if not,classi fied the main reason for inadequate guardianship as one of the following reasons:

(a) guardian was 70 years old or above;

(b) guardian was in poor health;

(c) guardian has irregular working hours, often has to travel for work, or work on night shifts;

(d) no family member or agency was willing to sign the guardianship agreement;

(e) other reasons, including guardians living in other places, patient is taken care of by other institutions or neighborhood committees, and so forth.

During the survey, the quality control staff visited the survey sites without prior notification and revisited 27households where there was clear evidence of incorrect information. The quality control staff randomly selected 1% of the survey forms to check for accuracy by phone. Forty-one out of the 43 forms re-checked by phone calls (95.4%) were accurate.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Microsoft Excel was used to construct the database. The data were analyzed using SPSS 19.0 software. Chi-squared tests with follow-up multiple comparison tests (using a Tukey-type multiple comparison method based on arcsin transformations of the original proportions[15]) were used to compare characteristics of respondents who did and did not adequately fulfill the responsibilities of guardians. Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify factors independently associated with inadequate guardianship. Differences between groups were considered statistically signi ficant whenp<0.05.

Table 1. Factors associated with the implementation of guardianship

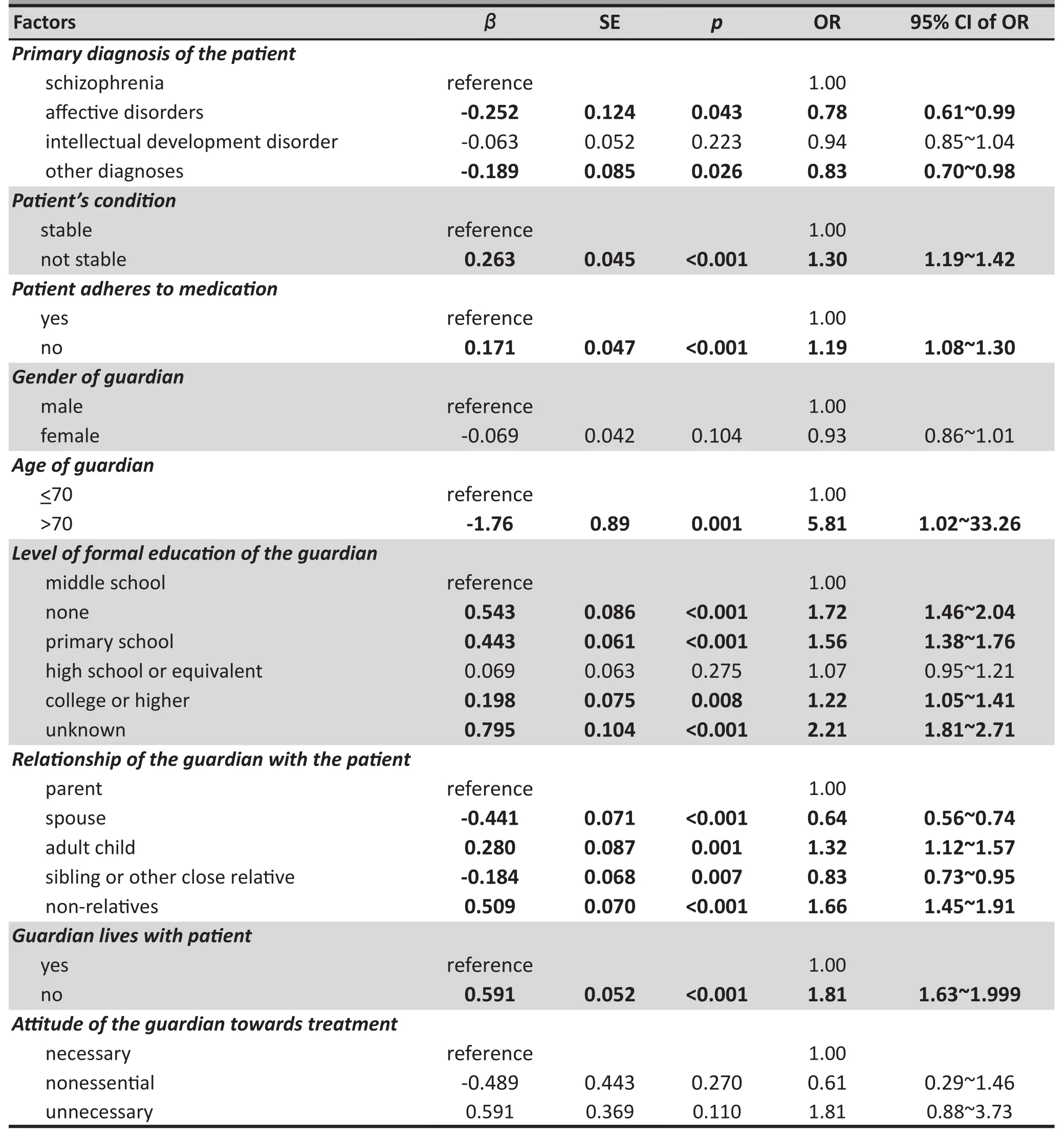

Table 2. Factors associated with the inadequate implementation of guardianship

3. Results

3.1 Factors associated with inadequate guardianship

The guardians of 4034 registered psychiatric patients completed the survey. As shown in Table 1, 3331(82.6%) of the guardians were adequately fulfilling the guardianship responsibilities and 703 (17.4%)were not. Bivariate comparison of these two groups of patients - those with or without adequate guardianship- indicated that inadequate guardianship was more common among patients whose clinical condition was unstable and among patients who did not adhere to medication. Guardians who did not adequately fulfill guardianship requirements were more likely to be over 70 years of age, to have a low level of education, to live separately from the patient, to be male, and to be unrelated to the patient or to be the patient’s parent.Somewhat surprisingly, the patient’s diagnosis and the guardian’s attitude about the necessity of treatment were only weakly associated with the adequacy of guardianship.

Several of the factors associated with inadequate guardianship are inter-related (for example, older individuals tend to have lower levels of education),so we conducted a multivariate logistic regression analysis to identify the factors that were independently associated with inadequate guardianship. As shown in Table 2, the strongest predictor of inadequate guardianship was advanced age (i.e., over 70) of the guardian. Other factors that were independently associated with inadequate guardianships (after adjusting for all other factors in the model) were not living in the same household as the patient, the patient’s unstable clinical condition, and the patient’s failure to adhere to using medication. The guardian’s gender and the guardian’s attitude about treatment were not signi ficantly associated with the adequacy of guardianship but the patient’s diagnosis, the guardian’s level of education, and the guardian’s relationship to the patient were signi ficantly associated with the adequacy of guardianship. Patients with schizophrenia were more likely to have inadequate guardianship than those with affective disorders (i.e., bipolar disorder or depressive disorder) or other disorders. Guardians with less than middle school education and (surprisingly!) those with college education were more likely to be inadequate guardians than those with middle school education.After adjusting for other factors, non-relatives and adult children were more likely than parents to be inadequate guardians while spouses and siblings were less likely than parents to be inadequate guardians.

3.2 Reasons for inadequate guardianship

As shown in Table 3, among the 703 households with insufficient guardianship, 557 (79.2%) were attributedby the interviewer to the advanced age of the guardian,53 (7.5%) were primarily due to poor health of the guardian, 27 (3.8%) were due to an irregular work schedule of the guardian, and in 9 (1.3%) households no family members were available or the family refused to take responsibility for the patient so there was a‘temporary’ guardian. As shown in the table, elderly guardians also tended to have less formal education and to hold a negative attitude towards treatment.Guardians who worked irregular hours were younger and had a higher level of education, but almost half of them did not live with the patient.

Table 3. Characteristics of the 703 guardians providing inadequate guardianship strati fied by the identi fied reasons for inadequate guardianship

4. Discussion

4.1 Main findings

This is a relative large study that conducted a structured assessment of the adequacy of familybased guardianship of community-dwelling individuals with mental disorders who are registered in the mental health monitoring system in one of Shanghai’s 19 districts. In most cases the legal guardians were parents (47%) or spouses (32%). We found that the guardianship network is working as intended in 83% of the 4034 households that were surveyed. These findings are similar to an earlier 2004-2005 study in another district of Shanghai by Zhang and colleagues[16]who reported that family-based care of community-dwelling individuals with mental disorders was good in 42.4%of the families, fair in 38.4% of the families, and poor in 19.2% of the families. These results indicate that the overall monitoring system for mental illnesses set up in Shanghai is working reasonably well.

As expected, our study found that guardians who did not live with the patient were less likely to provide adequate guardianship and the adequacy of guardianship was associated with patients’ diagnosis,clinical status, and adherence to medication. Previously,Feng[17]and Zhang[18]found strong associations between selected demographic characteristics of caregivers and the prognosis, rehabilitation and degree of disability among individuals with mental disorders. However, our results suggest that the demographic characteristic of guardians associated with the adequacy of guardianship are in a state of transition. The multivariate logistic regression analysis (which adjusted for age and other factors) found that (a)elderly guardians were much more likely to provide inadequate guardianship,(b) parents were more likely to provide inadequate guardianship than spouses or siblings but less likely to provide inadequate guardianship than adult children or non-relatives; (c) there was no significant relationship between the adequacy of guardianship and the gender of the guardian; and (d) guardians with a college education were more likely to provide inadequate guardianship than guardians with a middle school education. We expect that these findings are related to the rapidly changing social dynamics of families in urban China.

Based on the judgment of the interviewers (most of who were also the individuals who regularly provided follow-up services for the patients), advanced age and ill-health of the guardian was the main contributing factor in 87% of the 703 cases in which the guardianship was classi fied as inadequate. This has important policy implications. When deciding on the designation of a legal guardian for a person with a mental illness,the age and health status of the potential candidates should be given a higher priority than the type of relationship with the patient (which is the current way of assigning guardianship). There also needs to be regular monitoring of the adequacy of guardianship and a simple mechanism for transferring legal guardianship when the current guardian becomes too old or too ill to carry out the responsibilities of a guardian. Perhaps most importantly, alternative mechanisms for providing community-based support need to be developed to meet the needs of the growing number of patients for whom it is not possible to identify a suitable family guardian. Shanghai is one of the more economically advanced cities in China and is undergoing dramatic socioeconomic reforms. Diversifying the care of the mentally ill during this transition from a traditional family-oriented culture to a more individualistic culture is an important public health objective.

4.2 Limitations

This study of guardianship of individuals with mental disorders who are registered in Changning District of Shanghai has several limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the results. Some (6%) of the registered individuals were not located (most had moved without informing the monitoring system) and an unknown proportion of community-dwelling persons with mental disorders are not registered in the citywide monitoring system, so the quality of guardianship received by these unregistered individuals is unknown.This study was conducted in a Chinese city that has one of the most well-developed (and well-funded)community-based mental health delivery systems in China, so the results are probably not representative of the guardianship systems in other parts of the country. The study only assessed the experience of the legal guardians of the patients but many patients have multiple family members involved in their care -an important factor that probably affects the quality of guardianship that we did not consider. Finally, this is a cross-sectional study, so no causal relationship can be inferred between the quality of guardianship and the factors we found to be associated with inadequate guardianship.

A previous study by Hsiao[19]documented high levels of family burden among care-givers for patients with mental illnesses and found that female caregivers perceived having less social support and higher degrees of burden compared to male caregivers. Our study did not assess these factors. Future work about the adequacy of guardianship networks needs to integrate the assessment of the psychological status of the guardian as part of the overall evaluation of the adequacy and sustainability of guardianship-centered community services for mentally ill individuals.

4.3 Signi ficance

We found fairly good implementation of guardianship care for mentally ill individuals following the promulgation of the Shanghai Mental Health Regulations in Changning District. These results support the contention of Wang[20]that establishing specific laws and regulations and developing a comprehensive management system can help improve the sense of responsibility among legal guardians of individuals with mental disorders. However, this study also found that advanced age and poor health of the guardians were the main factors that are associated with inadequate care for the patients. This problem will probably become more acute in the coming decades because as a result of China’s one-child population policy most young urban residents do not have siblings who can take over the care of a mentally ill family member when the parents become too old to do so. Previous studies in China have uncovered other psychosocial factors related to inadequate guardianship or care-giving from the family,including high levels of economic burden, low social support, stigma and discrimination.[21,22]The assumption of China’s new mental health law and of policy makers that the family will continue to be responsible for community-dwelling individuals with mental disorders may not be viable over the long-term. Developing alternative models of providing high-quality, communitybased services for persons with mental disorders is an urgent task that needs to be undertaken as part of the roll-out and implementation of China’s new mental health law.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no con flict of interest related to this manuscript.

Funding

None

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Changning Mental Health Center, Shanghai, China.

Informed Consent

All participants provided written informed consent before participation in this study.

1. Jiang KD. [Psychiatry]. Beijing: People’s Health Publishing House; 2006. Chinese

2. Zhang MY. [Mental illness and disease burden].Zhong Hua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2001; 81(2): 67-68. Chinese

3. Yang G, Wang Y, Zeng Y, Gao GF, Liang X, Zhou M, et al.Rapid health transition in China, 1990-2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010.Lancet. 2013;381(9882): 1987-2015. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61097-1

4. Yang XH, Xie B, Huang JZ, Xu YF, Weng SU. [Attitude survey of the families of patients with schizophrenia patient].Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 1997; 9(4): 298-300. Chinese

5. Wang ZY, Zhang MY. [Survey of the social support on the patients with mental illness].Sichuan Jing Shen Wei Sheng.1997; 2: 73-77. Chinese

6. Chen Z, Yan F. [Survey of psychological status and family burden of the families of hospitalized patients with schizophrenia(Master Thesis)]. Fu Dan University; 2010.Chinese

7. Chen X, Huang DF, Lin AH, Li H, Liu P, Chen SZ, et al. [Causes and countermeasures study on psychiatric disabled adults in Guangdong province].Zhongguo Kang Fu Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2009; 24(10): 938-941. Chinese. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1001-1242.2009.10.021

8. Li CL, Zhao ZQ, Zhou B. [Epidemiological investigation of Ningxia mental disabilities].Ningxia Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2008;30(11): 1041-1042. Chinese. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1001-5949.2008.11.050

9. Hu MY, Shen TY. [An investigation of mental disability in schizophrenia and its risk factors related].Zhongguo Xing Wei Yi Xue Ke Xue. 2005; 14(10): 899-900. Chinese. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-6554.2005.10.014

10. Xie B, Liu XH, Zhang MY. [The mental health legislation in China].Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2002; 14(suppl): 44-46.Chinese

11. Chen HH, Phillips MR, Cheng H, Chen QQ, Chen XD, Fralick D, et al. Mental health law of the People’s Republic of China (English translation with annotations).Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2012; 24(6):305-321. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2012.06.001

12. The Legislative Affairs Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China. [Laws and regulations of the People’s Republic of China governing foreign-related matters]. Beijing: China Legal Publishing House; 2009.Chinese

13. Meng GR, Yao XW, Zhu ZQ, Zhang MY. [Construction of the information system on community mental health rehabilitation in Shanghai].Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2005;17(suppl): 35-37. Chinese. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2005.z1.013

14. Psychiatry Branch of the Chinese Medical Association.[Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders and Diagnostic Criteria,3rd Edition]. Shandong: Shandong Science and Technology Press; 2001. Chinese

15. Zar HG.Biostatistical Analysis (4th edition). Prentice Hall:New Jersey; 1999. p: 563-565

16. Zhang SB, Cheng YM, Zhang HH. [Status of the guardian of the community patients with mental illness].Sichuan Jing Shen Wei Sheng. 2008; 21(2): 111-112. Chinese. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1007-3256.2008.02.017

17. Feng H, Lu S, Zhang DJ, Feng ZZ, Wang Q, Xu JY, et al. [Study of family mental health and related factors of the 326 schizophrenia patients].Guo Ji Hu Li Xue Za Zhi. 2007; 26(7):707-708. Chinese. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-4351.2007.07.017

18. Zhang ZQ, Deng H, Chen Y, Li SY, Zhou Q, Lai H, et al. Crosssectional survey of the relationship of symptomatology,disability and family burden among patients with schizophrenia in Sichuan, China.Shanghai Arch Psychiatry.2014; 26(1): 18-24. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2014.01.004

19. Hsiao CY. Family demands, social support and caregiver burden in Taiwanese family caregivers living with mental illness: the role of family caregiver gender.J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(23-24): 3494-3503. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03315.x

20. Wang JY. [Questions about guardianship of the patients with mental illness].Zhongguo Shi Yong Yi Yao. 2009;4(13): 239-240. Chinese. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1673-7555.2009.13.206

21. Magliano L, Fiorillo A, De Rosa C. Family burden in long-term diseases: a comparative study in schizophrenia vs. physical disorders.Soc Sci Med. 2005; 61(2): 313-322. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.064

22. Phillips MR, Yang GH, Li S, Li Y. Suicide and the unique prevalence pattern of schizophrenia in mainland China: a retrospective observational study.Lancet. 2004; 364(9439):1062-1068. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17061-X

, 2014-07-01; accepted, 2015-01-29)

Qiongting Zhang graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in preventive medicine from the School of Public Health, Fudan University in 2010. She has been working in Changning District Mental Health Center,Shanghai since 2009. She is currently in charge of public mental health in the Department of Disease Control in this center. Her main research interests are the prevention and rehabilitation of mental illnesses.

上海市长宁区社区精神障碍患者家属监护状况的横断面评估

张琼婷*,陈浩,鞠康,牛昕,宋兰君,崔佳

精神病患者;监护;社区护理;精神卫生法;中国

Background:The disease burden associated with chronic psychiatric illnesses is high and is projected to grow rapidly. A community-based management system for persons with mental illness was established in Shanghai in 2012 based on the Shanghai Mental Health Regulations that were developed to conform with China’s new mental health law.Aim:Evaluate the guardianship services provided by family members to persons with mental illnesses living in the Changning District of Shanghai.Methods:The legal guardians of 4034 of the 4283 community-dwelling persons with psychiatric disorders living in Changning District who are registered in the Shanghai Information Management System of Mental Health were interviewed by local community health doctors and local neighborhood committee officials.The adequacy of guardianship was assessed based on standardized criteria (including the guardian’s regular attendance at mental health training sessions, and their level of assistance in the treatment, daily life, and rehabilitation of the patient) and the main reasons for inadequate guardianship were recorded.Results:The majority of guardians (3331, 83.6%) adequately ful filled their guardianship duties. Advanced age and ill-health of the guardian was the main contributing factor in 87% of the 703 cases in which the guardianship was classi fied as inadequate. Other factors associated with inadequate guardianship included the patient’s unstable clinical condition or failure to adhere to medication, and when the guardian did not live in the same household as the patient. The patient’s diagnosis, the guardian’s level of education, and the relationship between the guardian and patient were also associated with the adequacy of guardianship.Conclusions:The guardianship-based community services for mentally ill individuals in urban China works reasonably well. But the rapid aging of China’s population may gradually decrease the ability of China’s families to continue to assume this heavy burden. Alternative models of providing high-quality, communitybased services for persons with mental disorders need to be developed as part of the roll-out of China’s new mental health law.

[Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2015; 27(1): 18-26.

10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.214094]

Changning District Mental Health Center, Shanghai, China

*correspondence: 64319734@qq.com

背景:慢性精神病性障碍所致的疾病负担很高,预计还将快速增长。根据上海市精神卫生条例(为与中国新的精神卫生法相一致,该条例之后又经过了修订),2012年上海建立了基于社区的精神疾病患者管理系统。目标:评估居住在上海市长宁区的精神障碍患者家属提供的监护服务。方法:在上海精神卫生信息管理系统中登记的长宁区社区精神障碍患者共4283例,通过社区卫生服务中心家庭医生和居委会工作人员对患者法定监护人进行调查,实际调查4034人。监护的落实情况是根据规范标准进行评估的,这些标准包括监护人定期参加精神卫生培训课程,以及他们在患者的治疗、日常生活和康复方面的协助情况,也记录了监护不力的主要原因。结果:大多数监护人(3331名,83.6%)充分履行了监护职责。在划分为监护不力的703名监护人中,87%的主要因素为监护人年事已高、自身体弱多病。与监护不力相关的其他因素包括患者病情不稳定、未能坚持服药以及患者独居。患者的诊断、监护人的教育水平以及监护人和患者之间的关系也是监护落实的影响因素。结论:中国城市中,对精神障碍患者实行的以监护人为基础的社区服务工作相当有效。但是,中国人口快速老龄化可能会逐渐降低中国家庭继续承担这个沉重负担的能力。中国实施新的精神卫生法后,需要制定另一种模式,为精神障碍患者提供高品质的、以社区为基础的服务。

本文全文中文版从2015年03月25日起在www.shanghaiarchivesofpsychiatry.org/cn可供免费阅览下载

猜你喜欢

杂志排行

上海精神医学的其它文章

- Social media and suicide prevention: findings from a stakeholder survey

- Comparison of the personality and other psychological factors of students with internet addiction who do and do not have associated social dysfunction

- Psychosis risk syndrome is not prodromal psychosis

- Attenuated psychosis syndrome: bene fits of explicit recognition

- Case report of rabies-induced persistent mental symptoms

- Brief Chinese version of the Family Experience Interview Schedule to assess caregiver burden of family members of individuals with mental disorders