Incentive Measures and Performance Analysis of EU Paediatric Regulation

2015-02-21ZHANGQingwenYANGYue

ZHANG Qing-wen, YANG Yue

Incentive Measures and Performance Analysis of EU Paediatric Regulation

ZHANG Qing-wen, YANG Yue

Objective Tointroduce the incentive measures for paediatric drug research and development in European Union and to address the problem of lacking appropriate medicines for children. Methods Literature review was conducted through the PubMed, Web of Science and other database search by using the following key words, such as paediatric/pediatric drug development, incentives for paediatric/pediatric development and paediatric/pediatric regulation. Results and Conclusion The 2007 European Union (EU) Paediatric Regulation changed the status of lack of pediatric medicines in the EU by stimulating drug research and development through a series of incentive measures. The positive impact of the Pediatric Regulation on pediatric medicine development reflects an increase in the number of paediatric studies, drugs and information.

paediatrics; paediatric drug development; incentive measure; paediatric legislation

1 Introduction

The lack of medicines for the pediatric population is a longstanding problem in the European Union (EU) which had been highlighted in the 1960s. Most of the pediatric prescriptions used the unapproved medicines with strong sideeffect. ( For the purposes of this article the word “children” is synonymous with “pediatric population” and describes the age group between 0 and 18 years.) Dosage for children was inferred from adults. For example, of the dosage was in accordance with the weight ratio without pediatric pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic data. Safety and efficacy of drugs was also presumed to be the same as in adults, it was not the case.

There are a number of reasons that lead to the fact medicines can not be properly tested in children. One concern about conducting clinical trials in this vulnerable population is the ethical issue and the lack of volunteers for clinical trials. But the principal barrier is the reluctance of the pharmaceutical industry to develop medicines when there is an insufficient commercial return on investment. In October 2004, the European Commission launched a legislative proposal for an European regulation to overcome this barrier. Following intensive negotiations with the Member States and the European Parliament, the Regulation on pediatric medicines, which is based on a system of requirements and incentives, the Regulation entered into force on 26 January 2007[1]. It marks a radical change in the European Union in terms of encouraging the development of pediatric medicines and improving the availability of information on the use of medicines for children.

2 EU pediatric regulation

The EU pediatric legislation followed the pace with US regulations on pediatric drugs. FDA formulated Pediatric Rule in 1997 and the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act in 2002 which led the European member states to initiate the complex process of adopting new European legislation on pediatric medicines (Table 1). The European Commission consulted stakeholders at length before submitting a proposal of Regulation on pediatric medicinal products to the European Parliament in 2004. The final text was agreed with repeated amendments at the end of 2006 and entered into force on 26 January 2007.

Table 1 Legislative milestones in EU pediatrics

YearMajor milestones 1997The European Commission organized a round table of experts to discuss pediatric medicines at the EMA. The experts admitted the need to strengthen the legislation, in particular by introducing a system of incentives [2]. 1998An ICH E8 guideline titled “General Considerations for Clinical Trials” became the European guideline, which provided an outline of critical issues in pediatric drug development and approaches to the safe, efficient and ethical study of medicinal products. 2000The Council of (Health) Ministers adopted a resolution on 14 December 2000, urging the European Commission to draw up a legislative proposal (regulation). 2002ICH guideline became the European guideline “Note for Guidance on Clinical Investigation of Medicinal Products in the Pediatric Population” (ICH Topic E11), which has been in force since July 2002.In February 2002, the European Commission published a consultation paper on “Better Medicines for Children – Proposed Regulatory Actions in Pediatric Medicinal Products”. This paper represented one of the first steps of the Commission to address the problem of lacking pediatric medicines. 2001 – 2004The Directive (2001/20/EC) on Good Clinical Practice for Clinical Trials was adopted in April 2001, and came fully into force in May 2004. This Directive took into account some specific concerns about performing clinical trials in children, and in particular it laid down criteria for their protection in clinical trials. 2006The EC released the document on Ethical considerations for Clinical Trials performed in children intending to contribute to their protection as the subject of clinical trials as well as to facilitate a harmonized approval approach to clinical trials across the EU Member States. 2007 The EU Regulation on Pediatric Medicines was initiated in 2001 but adopted on 12 December 2006(Regulation (EC) No 1901/2006)and came into force on 26 January 2007. The Regulation established a legislative framework to allow increased availability of medicines specifically adapted and licensed for use in the pediatric population and improved quality of research in children [3]. As well as financial incentives and market exclusivity was given along with a system of requirements.

The Regulation on pediatric medicines was directly implemented throughout Europe. By the time the Regulation entered into force, about 100 million of children in the 27 member states of European Union benefited a lot.

The objects of the regulation are:

(1) To achieve high-quality pediatric clinical research ;

(2) Increase the availability of authorized medicines that are appropriate for children;

(3) Provide better information on medicines.

The regulation aims to achieve these objects and avoid the unnecessary clinical trials for children and the delays in adult drug approval. There must be a system of obligations, incentives and support to achieve these objects. Specifically, pediatric investigation plan (PIP) should be forced to submit, attaining high-quality pediatric clinical research and an incentive system of pediatric exclusivity to encourage more marketing authorizations of pediatric drugs[4].

(1) Pediatric investigation plan (PIP)

In order to address the problem of lacking pediatric drugs and promote the health of children under 18, increasing high-quality pediatric clinical research, there are provisions that in any applications for medicines approval, pharmaceutical companies must include a pediatric investigation plan (PIP) and submit pediatric data in compliance with an agreed PIP in Pediatric Regulation. As the basis of pediatric medicine development and approval, Pediatric Investigation plan (PIP) clearly pointed out that it is necessary to ensure the quality, safety and effectiveness of pediatric drug, the study methods and time arrangement are important as well. The study also includes the age-appropriate formulations and prescriptions, the need for juvenile animal studies and the required clinical trials.

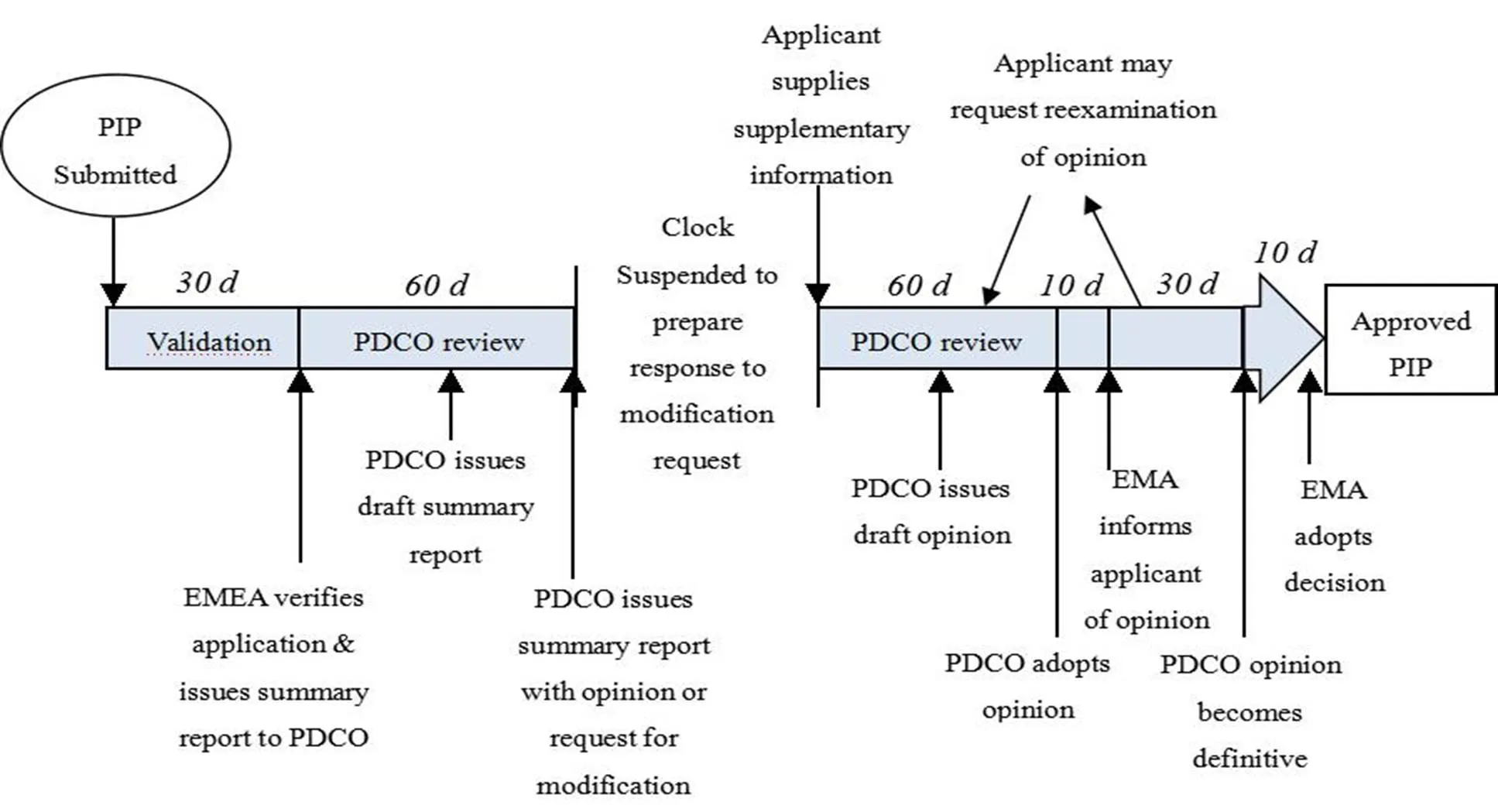

Figure 1 Process of obtaining EMA approval of a PIP[5]

In the EU, the process for obtaining European Medicine Agency (EMA) approval for a PIP is complex and long (Figure 1). Pharmaceutical companies should submit a proposal to the Agency in advance. Basically, it should be submitted before the completion of the first clinical trials. Two members of the Pediatric Committee (PDCO) and a staff member of the Agency will examine the research method, drug prescription and expected effect. Then, they can determine whether to approve or not. The procedure will last around 120 days, during this period of time, pharmaceutical companies can be requested or allowed to answer questions or modify their proposal. The Committee’s opinion will be transformed into a legally binding decision (signed by the EMA Executive Director). The decisions are published on the EMA website.

The duty of PDCO is to review and agree the waivers or deferrals of PIP. PDCO can ask the marketing authorization holders to carry out additional pediatric studies which they had not planned. The General Court can confirm that the PDCO and the EMA have the right to impose obligations on companies to conduct pediatric studies for indications that the company does not intend to develop. However, the grant of an Market Authorization Application (MMA) for any pediatric drug and adults drug is made by the Committee of Human Medicinal Products (CHMP).

(2) Waiver PIP or deferral PIP

Obviously, not all medicines have the potential to meet pediatric needs. Waivers can be granted if:

① The disease or condition only occurs in adults;

② The medicine is likely to be unsafe or ineffective for children;

③ The medicine does not have a significant therapeutic benefit.

In order to avoid unnecessary administrative procedures, waivers can be granted for a condition or a class of products rather than one product after another. Waivers can be granted for the whole pediatric population (full waiver) or some subsets only (partial waiver) and can be revoked by the Committee with a three-year delayed effect.

For safety reasons, deferrals PIP can be granted by the authority. Pediatric medicines development is generally performed once safety and efficacy data have been obtained in adults and only after the successful production of adults drugs.

In order to solve the problems of pharmaceutical manufacturers’ reluctance to produce the pediatric medicine, small pediatrics market, high research costs and the irrecoverable pediatric R&D investment, EU Pediatric Regulation established the pediatric exclusive incentive system to encourage the manufacturers to produce more pediatric medicines for children. Under the regulation, there are various incentives available for pharmaceutical industry:

• A six-month extension to the SPC for those products that have an SPC grant;

• For orphan medicines, an additional two years’ marketing exclusivity added to the existing ten years awarded under the Orphan Regulation;

• For off-patent products, a new type of authorization called a pediatric use marketing authorization (PUMA), which has the reward of a period of data and marketing protection (8 years +2 years) for new studies. This 10-year period of marketing protection can be extended by a further year (8+2+1) if an indication of significant clinical benefit is authorized in the first eight years.

(1) Six-month extension to the SPC

Holders of patented medicines can receive a single extension of the Supplementary Protection Certificate(SPC) by six months, provided that: ① they have completed all of the measures in the Pediatric Investigation Plan regardless of the negative results for the studies; ② the results of all the studies are included in the product information; ③ the product is authorized by centralized procedure or authorized in all member states (this only concerns very few medicines that still use a national rather than the EU authorization procedure); ④ they have obtained a Certificate; ⑤ the extension application is made to the National Patent Office (s) at least two years before expiry of the Certificate[6].

The requirements and the financial incentives is independent of each other. Thus, a marketing authorization holder who has been in compliance with the agreed PIP may not meet all the conditions to obtain the reward. The applicant may not have an SPC to extend or be eligible for an SPC extension if the product is not authorized in each member states or the approval is obtained too late; AstraZeneca, for example, has lost the opportunity of extending the SPC for esomeprazole (Nexium) as the SPC certificate expired.

(2) Extension of marketing exclusivity for orphan drugs to twelve years

Under the Orphan Drug Regulations, medicinal products that are designated as orphan medicinal products gain ten years of marketing exclusivity on the granting of a marketing authorization for the orphan indication. They cannot receive a double incentive. Therefore, instead of an extension of the SPC, the 12 years period of orphan market exclusivity is preferred if the requirements are met.

About 15% of PIP applications are for orphan-designated medicinal products. A large proportion of rare diseases mainly affect children and 30% are exclusively pediatric. According to the EMA’s 2012 report submitted to the Commission, no orphan medicinal product benefited from this incentive.

(3) Grant of Pediatric Use Marketing Authorization (PUMA)

A new type of marketing authorization is created by the Regulation to encourage the development of off-patent medicines, which are lack of commercial interest. The Pediatric Use Marketing Authorization (PUMA) requires an agreed PIP, but only for the pediatric indication and pediatric dosage form. All products that have an authorized pediatric indication are required to display a symbol with a blue letter “P” on the package label to ensure that they are readily identifiable. It benefits for ten years of protection (eight years of data exclusivity followed by an additional two year s of market protection).

Applications have to contain the results of studies in compliance with a PIP. Applicants can have access to free scientific advice and they can rely on published literature and data or refer to data owned by a different marketing authorization holder provided that the appropriate period of data protection was expired. The products are only for pediatric population. The incentives associated with a PUMA are relatively weak. Nevertheless, they can encourage the development of new pediatric formulations from the older products. Applications for PUMA may choose centralized, decentralized or national procedures, if authorized, they will benefit from 10 years market protection.

Despite the flexibility of this regulatory and the easy access to the relevant data, it takes a long time to get the PUMA. The first and the only PUMA case was the ViroPharma Company’s Buccolam (midazolam) which was authorized with the centralized procedure in September 2011. Up until 2012, only 26 (2%) PIP or waiver applications were specifically for children with a formulation appropriate to age. Recently, the number of applications seems to be in decline; there were four in 2010, none in 2011 and only one in 2012.

(1) Information and transparency

The purpose of promoting public health and avoiding the duplication of pediatric research can be achieved by improving transparency and making information on pediatric medicines more accessible to public. According to the Pediatric Regulation, all protocol and results on pediatric trials in the European database (EudraCT) should be accessible to the public. All decisions on PIPs such as, deferrals or waivers of the pediatric development should be published regularly on EMA website[7]. Moreover, once the drug approval is granted, the results of the pediatric studies, any waivers or deferral, must be included in the product information and instructions.

The Pediatric Regulation requested that the EMA to establish an European Pediatric Research Network (Enpr-EMA) which could integrate the existing networks, centers and pediatric research institutions together, and it was set up in 2011. Its objectives were to coordinate studies relating to pediatric medicinal products and avoid duplication of studies and testing in children[8]. An annual conference is held for the pharmaceutical industry to exchange information on pediatric trials, including their feasibility and opportunities for participation. Currently, 18 research institutions have met the requirement and 34 have submitted self-assessment reports[9].

(2) Public research fund

Generics have limited commercial interest and generally most pharmaceutical enterprises are not interested in developing pediatric drugs. However, they are the majority of medicines for children. In addition, these medicines do not have enough evidence of safety and efficacy. There is an urgent need to study them, and the Regulation established the legal basis for EU to use public fund for the generics research. 16 projects covering at least 20 generics ingredients had won EU fund support until 2012, amounting a total of EUR 80 million[10].

To ensure that the funds were put into the urgent pediatric research, the European Medicines Agency Pediatric Committee (PDCO) made a list of non patent medicinal products and regularly updated it. The top priority areas included the development of pharmaceutical formulation for all ages of pediatric population as well as neonates and infants research. The EMA adopted a revised provisional priority list in July 2013 after a public consultation. The list won a fund from the EU’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7)[11].

3 Evaluation for the implementation of pediatric regulation

Since the Pediatric Regulation came into effect, it has brought a lot of positive impacts. The most direct effect is the incentive for manufacturers to invest in pediatric clinical research and more approvals of pediatric medicine as well as much safer information on pediatric medicine.

Pediatric exclusivity incentives not only make the pharmaceutical manufacturers take back all the pediatric research investment, but also some profit which will provide financial support for future research[12]. Table 2 shows the information on products which have benefited from the pediatric exclusivity recently. Although the data shows the number of products benefited from the 6-month extension of the SPC has increased steadily. It is worth noting that the products that had been rewarded before are still in the list, and the number of “new” listed products hasn’t increased year by year. So far no orphan medicinal product has benefited from this policy. In 2011, the first application for a PUMA was submitted to the EMA and authorized through the centralized procedure, which was the only one PUMA granted up until 2012.

Table 2 Summary of products which have benefited from the pediatric exclusivity of SPC/PUMA/Orphan market exclusivity extension

The type of pediatric exclusivitySPC(number of benefited products)PUMA(number of benefited products)Orphan Market Exclusivity extension(number of benefited products)Note In 20093 [13]00—— In 20108 [14]00The number of SPC including 3 products that had been rewarded before and 5 new rewarded. In 20119 [15]10 The number of SPC including 6 products that had been rewarded before and 3 new rewarded. In 20121300The number of SPC including 7 products that had been rewarded before and 6 new rewarded.

Source: 2009 - 2012 report to the European Commission on rewards and incentives under the Paediatric Regulation

Note: SPC = Supplementary Protection Certificate; PUMA = Pediatric Use Marketing Authorization.

This article evaluates the implementation effect of Pediatric Regulation from its three objectives respectively.

Many essential medicines neither have child-size dosage nor enough information about their efficacy and safety for children. In order to address the research needs for children’s medicines, it is essential to improve the quality and quantity of pediatric clinical trials research. Clinical trials involved children require careful ethical review and approval[16].

For the first objective of Pediatric Regulation, namely, to conduct a better and safer pediatric research for children, EMA has made positive effort. By the end of 2012, EMA had made 598 resolutions agreeing PIP of all 862 (Table 3), representing 70% of all resolutions. A full waiver (264) accounted 30% of all EMA decisions. This did not include modifications on agreed PIPs and negative opinions.

Table 3 Resolutions on pediatric investigations plans and waivers

200720082009201020112012Sum Number of Decisions on PIPs and full waivers 12124189252151134862 Total number of PIPs28112120110687598 Full waivers 104368514547264 Resolution on a modification of an agreed PIP0851108153166486

Figure 2 shows the frequency in which pediatric therapeutic areas were addressed by the agreed PIPs. Few PIPs were submitted exclusively for the therapeutic area of neonatology, although this subpopulation was in urgent need of medicines development. In fact, the neonate was covered under each therapeutic area and about one in four agreed PIPs included the neonatal subpopulation.

Figure 2 Therapeutic areas addressed by the pediatric investigation plans (2007-2011)

Table 4 shows that, based on EudraCT data, the number of pediatric clinical trials was stable with an average of 350 per year; however, simultaneously, the number and proportion of pediatric trials were stable despite the general decrease in numbers of clinical trials in EudraCT (adults and children).

Table 4 Pediatric clinical trials by year of authorization

20052006200720082009201020112012 Pediatric trials (number) 254316355342404379334332 Pediatric trials that are part of an agreed PIP (number)212616307676 Proportion of pediatric trials that are part of an agreed PIP among pediatric trials (%)1012482323 Total trials of adults and children (number) 33503979474945124445402638093698 Proportion of pediatric trials of all trials (%)887891099

Since the Pediatric Regulation came into effect, the number of pediatric study participants in clinical trials had significantly increased to more than 60,000 in 2012, without significant increase in number of trials. The main increase was for children. The number of pediatric study participants was highly variable across trials and years (Table 5), but overall, there was an increase in the number of pediatric participants.

Table 5 Number of children planned to be enrolled in clinical trials, by age

Number of subjects200420052006200720082009201020112012 Preterm newborns 000002078221151474 Newborns0009856416910551172 Infants and toddlers20576733098205459520391079818776 Children02382326663200298824231709125033 Adolescents025936832430205205544081820315879 Sum of above2062643025332894305970291214926262433

Neonates are the most neglected group when it comes to medicines development, and it is hard to get any proper data on efficacy and safety of pediatric drug. The EMA requests more neonates and infants clinical trials should be carried out to obtain these data in a safe way. Currently, 30% of the pediatric investigation plans include studies for neonates. More neonates and infants (26%) have been included in trials in recent years[18].

The second major objective of the Pediatric Regulation is to ensure that more medicines available for children in the European Union. Due to the long duration of medicine development and authorization procedures, we had collected the data over the comparatively short period of time since the Pediatric Regulation came into force. This section presents data on new pediatric drug, new indications and new dosage forms for children.

The medicines can be classified based on the type of authorization procedures. The mandatory scope for centrally authorized products includes medicines for acquired immune deficiency syndrome, cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, diabetes mellitus, auto-immune diseases and other immune dysfunctions and viral diseases. For variations, the Table 6 shows the data. All the analysis and tables exclude generic biosimilar, homeopathic, traditional herbal, and well-established medicinal products or duplicate marketing drugs.

Table 6 Overview of pediatric medicine changes (by year of authorization, or variation)

20072008200920102011Sum Initial marketing authorization (new active substance) with a pediatric indication : ·Centralized procedure, linked to requirements of the Pediatric Regulation ——022610 ·Centralized procedure, not linked to requirements of the Pediatric Regulation 10650021 Reference: all new centrally authorized medicines(with or without a pediatric indication)3925411730152 ·National (DCP, MRP) procedure 002013 Newly authorized pediatric indications for already authorized medicine : ·Centralized procedure, linked torequirements of the Pediatric Regulation————211518 ·Centralized procedure, not linked to requirements of the Pediatric Regulation7662021 Reference: Centralized procedure, all extensions of indication1728312131128 ·National (DCP, MRP) procedure linked to requirements of the Pediatric Regulation ——135312 ·National (DCP, MRP) procedure not linked to requirements of the Pediatric Regulation5382321 Total Pediatric indications EU 2216281227105 Newly authorized pharmaceutical forms for pediatric use for already authorized medicine: ·Centralized procedure (line extensions) linked torequirements of the Pediatric Regulation ————0033 ·Centralized procedure (line extensions) not linked to requirements of Pediatric Regulation3122412 Reference: Centralized procedure, all line extensions 2115282321109 ·National (MRP, DCP) procedure linked to requirements of the Pediatric Regulation————2316 ·National (MRP, DCP) procedure not linked to requirements of the Pediatric Regulation 112015

Note: DCP = Decentral procedure, MRP = Mutual recognition procedure

“——” = Not applicable as requirements of Article 7 and 8 of the Pediatric Regulation were not in force.

From 1995 to 2006, 108 of all 317 centrally authorized medicines (Figure 3) had a pediatric indication (cumulative, 34%). Since the Pediatric Regulation came into effect, (from 2007 to 2011), 31 new medicines had been centrally authorized for pediatric use out of 152 (20%) (Table 6). The number of new medicines authorized per year, either for adults or children, over the same period had decreased.

Figure 3 Situation by December 2006: proportion of medicines among the 317 centrally authorized medicines

In addition, as for the medicines already on the market, 72 new pediatric indications were authorized.

Moreover, 26 new dosage forms of drugs already on the market were approved for pediatric use, including 15 centrally authorized medicines and 9 pediatric drugs in accordance with the requirements of the Pediatric Regulation.

The third main objective of the Pediatric Regulation is to improve information of medicinal products for pediatric population. On the one hand, new pediatric data should help the regulatory authorities determine the pediatric needs. On the other hand, additional information should be assessed and made available for medical staff and medication group.

The increase of pediatric drug information can be solved by adding pediatric information to the Product information (SmPC and / or Package Leaflet). This can come from pediatric study results or other pediatric related information (e.g, non-clinical study results, findings of pharmacovigilance, or PDCO’s opinions). The Pediatric Regulation has triggered update of the SmPC for pediatric information in a substantial number of cases as well as giving public access to the evaluation of pediatric data in assessment reports (more than 100 so far). Table 7 summarizes the pediatric-relevant changes to product information since the Pediatric Regulation came into effect.

Table 7 Increased information on medicines for pediatric use

20072008200920102011Sum Dosing information for children added to SmPC ·Centralized procedure141416152079 ·National (DCP, MRP) procedure linked to requirements of the Pediatric Regulation————12710 ·National (DCP, MRP) procedure not linked to requirements of the Pediatric Regulation 15121361965 Pediatric study results added to the SmPC ·Centralized procedure111211232077 Pediatric safety information added to the SmPC ·Centralized procedure81120*28* Statements on deferral or waiver included or added to SmPC ·Centralized procedure002283161 ·National (DCP, MRP) procedure****** Other pediatric information added to SmPC ·Centralized procedure71315121966 PIP data failing to lead to pediatric indication——01225

Note: DCP = Decentralized procedure. MRP = Mutual recognition procedure.

“——” = Not applicable as requirements of Article 7 and 8 of the Pediatric Regulation were not in force.

“*”= No data sufficient for analysis.

Even the additional information on waivers granted is meaningful for the pediatric population in that such waivers allow the identification of medicines that do not deserve a pediatric development, including the unsafe or ineffective drugs assessed by the regulatory authority. At the same time, it can help avoid unsafe label drugs.

4 Conclusions

There is no doubt that the Pediatric Regulation places a considerable additional burden on pharmaceutical companies for they have obligations to carry out pediatric research, but they can get a considerable of incentives and rewards. This approach is good because market forces alone are not sufficient to stimulate adequate research on pediatric drugs. Measuring and analyzing the impact of any new legislation is hard. In a relatively short time the Pediatric Regulation has already delivered on every one of its objectives compared with the long development of new medicines, that is, to develop more and better pediatric medicines and information. Based on the experience accumulated so far, the objectives of the Pediatric Regulation can be achieved. In the future, more pediatric information will be provided for children of all ages.

[1] Dunne J. The European Regulation on Medicines for Paediatric Use [J]. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews, 2007, 8 (2): 177-183.

[2] European Medicines Agency. The European Paediatric Initiative: History of the Paediatric Regulation (EMEA/17967/04 Rev 1) [EB/OL]. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Other/2009/09/WC500003693.pdf, 2013-12-31.

[3] John P. Griffin, John Posner, G. R. Barker. The Textbook of Pharmaceutical Medicine [M]. John Wiley & Sons, 2013: 295-305.

[4] Mary Smillie. A Difficult First Five Years with the EU pediatric Regulation [EB/OL]. http://www.rouse.com/media/56682/02_sra_feb_2013_eu_paediatric_regulation_smillie_pdf.pdf, 2013-02-10.

[5] Alan M. Hoberman, Elise M. Lewis. Pediatric Nonclinical Drug Testing: Principles, Requirements, and Practices [M]. Wiley, 2012: 79-92.

[6] Andrew E. Mulberg , Dianne Murphy, Julia Dunne,Pediatric drug development: concepts and applications [M]. John Wiley & Sons, 2013: 149-155.

[7] Adriana Ceci, Mariana Catapano, Cristina Manfredi,. Changes in Research and Development of Medicinal Products since the Paediatric Regulation, Drug Development – A Case Study Based Insight into Modern Strategies [EB/OL]. http://www.intechopen.com/books/drug-development-a-case-study-based-insight-into-modern-strategies/changes-in-research-and-development-of-medicinal-products-since-the-paediatric-regulation, 2013-12-31.

[8] Rocchi F, Tomasi P. The Development of Medicines for Children: Part of a Series on Pediatric Pharmacology [J]. Pharmacological Research, 2011, 64 (3): 169-175.

[9] Ralf Herold. Recent Developments for Paediatric Anti-cancer Medicines and Links to EPOC Project [R]. London: EPOC – European Paediatric oncology Off-patent medicines Consortium–EPOC Doxorubicin trial meeting, 2013-09-05.

[10] European Commission. Better Medicines for Children From Concept to Reality [EB/OL]. http://ec.europa.eu/health/files/paediatrics/2013_com443/paediatric_report-com(2013)443_en.pdf,2013, 2013-12-31.

[11] EMA. Priority List of Off-patent Medicines [EB/OL].

http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/regulation/document_listing/document_listing_000092.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac05800260a4, 2013-12-31.

[12] YANG Li, LUO Cun, CHEN Jing. Study on Pediatric Drug Exclusivity [J]. Journal of China’s New Drug, 2009, (9): 773-777.

[13] EMA. 2009 Report to the European Commission on Rewards and Incentives under the Paediatric Regulation [EB/OL]. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Report/2011/05/WC500106263.pdf, 2013-12-31.

[14] EMA. 2010 Report to the European Commission on Rewards and Incentives under the Paediatric Regulation [EB/OL]. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Report/2011/05/WC500106262.pdf, 2013-12-31.

[15] EMA. 2011 Report to the European Commission on Rewards and Incentives under the Paediatric Regulation [EB/OL]. http://ec.europa.eu/health/files/paediatrics/2012-07_paediatric_regulations.pdf, 2013-12-31.

[16] WHO. Drug: Pediatric Drug [EB/OL]. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs341/zh/index.html, 2013-12-31

[17] EMA. 2012 Report to the European Commission on Rewards and Incentives under the Paediatric Regulation [EB/OL]. http://ec.europa.eu/health/files/paediatrics/2012_report_paed_regulation.pdf, 2013-12-31.

[18] EMA. Successes of the Paediatric Regulation after 5 Years [EB/OL]. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Other/2013/06/WC500143984.pdf, 2013-12-31.

[19] EMA. 5-year Report to the European Commission [EB/OL]. http://ec.europa.eu/health/files/paediatrics/2012-09_pediatric_report-annex1-2_en.pdf, 2013-12-31.

Author’s information: YANG Yue, Professor. Major research area: Pharmaceutical regulations, drug policy. Tel: 13998236315, E-mail: yyue315@126.com