Context and Content: From Language to Thought

2011-12-05FRANOISRECANATI

FRANÇOIS RECANATI

(Institut Jean-Nicod, France)

1.SPEECH ACT THEORY

I was raised as a continental philosopher (in Paris, in the seventies).Initially a disciple of Lacan, I discovered analytic philosophy by chance.I had noticed similarities between Lacan’s approach to natural language and (what I knew of) ordinary language philosophy as practiced in Oxford in mid-twentieth century.Like Lacan, ordinary language philosophers criticized the attempt to understand natural language by studying the constructed languages of logic.So I started investigating ordinary language philosophy to see how much could be extracted from it in the service of a broadly Lacanian conception.It took me little time to realize that the analytic way of doing philosophy, with its characteristic clarity and simplicity, was more to my taste than the obscurity and pomposity which plagued continental philosophy in general, and Lacanian theorizing in particular.I myself became an analytic philosopher, and started interacting with philosophers in the UK and the US, while doing my best, with a few enlightened colleagues from various European countries, to develop that sort of philosophy on the continent.

Ordinary language philosophers thought important features of natural language were not revealed, but hidden, by the logical approach initiated by Frege, Russell and the logical positivists.They advocated a more descriptive approach and emphasized the ‘pragmatic’ dimension of language.Language isused, and language use, or the activity of speech, deserves to be studied in its own right.Moroever, its study is likely to shed light on linguistic forms and their meaning, which meaning is indissociable from the way the expressions are used.Ordinary language philosophy thus initated a ‘pragmatic turn’ in the philosophy of language and contributed to the development of a new linguistic discipline: the so-called pragmatics.The fact that my entry point into analytic philosophy was via ordinary language philosophy explains why my initial contributions to the philosophy of language were in that area.

Speech act theory (Austin 1975; Searle 1969) is the core of pragmatics and I started my new career as a speech act theorist.Speech act theory is concerned with communication—not communication in the narrow sense of transmission of information, but communication in a broader sense which includes the issuing of orders, the asking of questions, the making of apologies and promises, etc.According to the theory, a speech act is more than merely the utterance of a grammatical sentence endowed with sense and reference.To speak is also todosomething in a fairly strong sense—it is to perform what Austin called an ‘illocutionary act’.

Illocutionary acts are generally introduced ostensively, by examples—as I did above; and they are distinguished both from the act of merely saying something (‘locutionary’ act) and from the act of causing something to happen by saying something (‘perlocutionary’ act, e.g.frightening, convincing, etc.).The nature of the intermediate category of ‘illocutionary acts’ remains unclear, however.The pioneers of speech act theory, Austin and Searle, advocated an institutional or conventional approach.Like Malinowski, one of the early advocates of the pragmatic turn in the study of language,[注]See Malinowski 1923.they used to insist on thesocialdimension of language as opposed to its cognitive or representational function.In their framework the illocutionary acts performed in speech, like the acts that are performed in games (e.g.‘winning a set’ in tennis), are governed by rules, and exist only against a background of social conventions.As pragmatics developed, however, it is thepsychologicaldimension of language use that came to the forefront of discussions, in part as a result of Grice’s work on meaning and communication.

In his famous 1957 article “Meaning”, Grice defined a pragmatic notion of meaning: the notion ofsomeone’smeaning something by a piece of behaviour (a gesture, an utterance, or whatnot).Grice’s idea was that this pragmatic notion of meaning could be used to analyse the semantic notion, i.e.what it is for a linguisticexpressionto have meaning.Strawson soon pointed out that Grice’s pragmatic notion of meaning could also be used to characterize the elusive notion of an illocutionary act (Strawson 1964).The view that illocutionary acts are essentially conventional acts (like the acts which owe their existence to the rules of a particular game) was dominant in speech act theory until Strawson established a bridge between Grice’s theory of meaning and Austin’s theory of illocutionary acts.The alternative, Gricean approach advocated by Strawson marked a ‘cognitive turn’ within pragmatics.The crucial notion became that of an audience-directed intention and the crucial mechanism through which one is able to read someone else’s mind and decipher his or her intentions.It is to the development of the new framework that—along with others like Bach and Harnish (1979) and Sperber and Wilson (1986)—I contributed in my early publications, especially the bookMeaningandForce(1987—originally published in French asLesEnoncésperformatifs, 1981).

I said above that a perlocutionary act consists in bringing about certain effects by an utterance.For example, by saying to you“It is raining”, I bring it about that you believe that it is raining.Now, according to the Grice-Strawson analysis, to perform theillocutionaryact of asserting that it is raining is (in part) to make manifest to the addressee one’s intention to bring it about, by this utterance, that the addressee believes that it is raining.(This is not the full story, of course.) An illocutionary act, therefore, involves the manifestation of a corresponding perlocutionary intention.But there is a special twist which the suggested analysis inherits from Grice’s original conception of meaning: the intention must be made manifest in a specially ‘overt’ manner.Not only must the speaker’s intention to bring about a certain belief in the addressee be revealed by his utterance, but his intention to reveal it must also be revealed, and it must be revealed in the same overt manner.This characteristic (if puzzling) feature of overtness is often captured by considering the revealed intention itself asreflexive: A communicative intention, i.e.the type of intention whose manifestation (and recognition) constitutes the performance of an illocutionary act, is the intention to produce a certain perlocutionary effect (e.g.bringing about a certain belief in the addressee) via the addressee’s recognition ofthisintention.

In my bookMeaningandForceI offered a systematic critique of the conventionalist picture and an elaboration of the alternative framework.The cornerstone of the conventionalist approach defended by Austin and Searle was the notion of a ‘performative formula’.Austin had noticed that one can perform an illocutionary actVby saying that oneV’s.One can promise by saying “I promise” or one can order by saying “I order”.The performative formula, e.g.“I promise”, is for Austin and Searle a form of words which, by convention, enables the speaker to perform the act which it names (here the act of promising).It is, moreover, constitutive of the acts in question that there are formulas which by convention serve to perform them.I criticized that view and tried to show that, within an appropriate version of the Gricean framework, one can account for performative utterances without departing from standard principles of compositional semantics.While Austin and Searle treated the ‘performative formula’ as endowed with certain powers in virtue of brute conventions, I argued that their efficacy is best explained by appealing to the nature of communicative acts.If to communicate something is to make manifest one’s intention to do so, then it is unsurprising that one can perform a communicative act by declaring that one does.

2.THE PRAGMATICS OF WHAT IS SAID

In the new framework, an utterance is seen as a meaningful action, i.e.an action which provides interpreters with evidence concerning the agent’s intentions.What distinguishes communicative acts from other meaningful actions is what can be inferred from the evidence: A communicative act is an act which provides evidence of a certaincommunicativeintentionon the part of the speaker.In other words, the speaker’s intention to communicate something is what explains his utterance, considered as a piece of behaviour.From this point of view, the content of the communicative act—whatis communicated—is the total content of the communicative intentions which can be inferred from it.Let us call this the utterance’s communicative meaning, distinct from the literal or conventional meaning of the sentence (determined by the grammar).Understanding isessentiallyan inferential process in this framework, and the conventional meaning of the sentence provides only part of the evidence used in determining the communicative meaning of the utterance.

On this picture, communication does not essentially rely on the coding of information.Communication is possible even if one does not share a language.Even without a common language, one can manage to let the hearer recognize one’s communicative intentions.And when the communicators do share a language, what they communicate using that language typically goes well beyond what they literally encode in their words.

Grice’s theory of conversational implicatures—a particular application of his general theory of meaning—shows how one can communicate something implicitly (Grice 1989).On Grice’s account, implicatures are derived through an inference which enables the interpreter to grasp the speaker’s communicative intention despite the fact that it is not articulated in words.The inference makes use of two crucial premises (in addition to background knowledge): (1) the fact that the speaker has said what she has said, and (2) the fact that the speaker, qua communicator, obeys (or is supposed to obey) the rules of communication or, as Grice puts it, the ‘maxims of conversation.’ Conversational implicatures are only a special case, however.Because of the role played by the first premise in the inference through which they are derived, conversational implicatures belong to the ‘post-semantic’ layer of interpretation.This means that, in order to derive the implicatures of an utterance, an interpreter must start by identifying what the speaker literally says (the utterance’s ‘semantic content’).But pragmatic inference isalsorequired to identify what is said—or so I have argued since the early eighties.

In“The Pragmatics of What is Said”(1989) and subsequent work, I drew a distinction between primary and secondary pragmatic processes.Secondary pragmatic processes are those which presuppose the prior identification of what is said (as in Grice’s picture), while primary pragmatic processes are those that are involved in the determination of what is said.Shortly afterwards, in the second part of my 1993 bookDirectReference(a second part entitled “Truth-Conditional Pragmatics”, like the book I published in 2010), I drew a further distinction between two types of primary pragmatic processes: saturation and modulation.

Saturation is a pragmatic process triggered by something in the sentence itself—some linguistic expression which introduces a slot to be contextually filled or (equivalently) a free variable to which a value must be contextually assigned.To compute the proposition expressed by an utterance, it is necessary to assign contextual values to indexicals, (unbound) pronouns etc.For example, if the speaker uses a demonstrative pronoun and says “She is cute,” the hearer must determine who the speaker means by “she”in order to fix the utterance’s truth-conditional content.Likewise, if I say “John is ready”but the context does not provide an answer to the question:“ready for what?”, I have not said anything definite; I haven not expressed a complete proposition.Saturation, so understood, ismandatory: No proposition is expressed unless a value is assigned to the variable.A ‘slot’ has to be contextually filled, which leaves the utterance semantically incomplete in case it remains unfilled.

With modulation, the situation is quite different.What modulation does is tomodifywhatever content the expression literally possesses (e.g.by making it more specific, as in free enrichment, or less specific, as in sense extension).Since the expression at issue already possesses a determinate content, modulation is not a mandatory process, as far as semantic interpretation is concerned.It is optional and takes place only to make sense of what the speaker is saying.In other words what triggers the contextual process of modulation is not a property of the linguistic material, but a property of the context of utterance.The meaning of words is adjusted through some kind ofpragmaticcoercion.As I put it in my bookLiteralMeaning, in which I summarize that line of research.

Sense modulation is essential to speech, because we use a (more or less) fixed stock of lexemes to talk about an indefinite variety of things, situations and experiences.Through the interaction between the context-independent meanings of our words and the particulars of the situation talked about, contextualised, modulated senses emerge, appropriate to the situation at hand.(Recanati 2004: 131)

The emphasis on the role of pragmatic factors in the determination of what is said led me to revive the literalism/contextualism debate which had marked the middle of the twentieth century.According to the family of views I call ‘literalism’, the proposition expressed by an utterance is, by and large, fixed by the conventions of the language.According to contextualism, the alternative position reminiscent of ordinary language philosophy which I set out to defend inLiteralMeaning, an utterance expresses a fully determinate, truth-evaluable proposition only in the context of a speech act.The rules of the language by themselves are not sufficient to endow a sentence with truth-conditional content.

To be sure, everybody accepts that sentences containing indexicals express a proposition only with respect to context.This, however, was not considered as a major threat to the literalist picture for two reasons.First, saturation itselfisgoverned by the conventions of the language.The meaning of an indexical is, or includes, atoken-reflexiverulewhich tells us how, for each particular token of the expression, we can determine the content carried by that token as a function of the circumstances of utterance.(Thus the meaning of ‘I’ is the rule that a token of that word refers to the producer of that token, the meaning of ‘today’ is the rule that a token of that word refers to the day on which the token is produced, the meaning of ‘we’ is a rule that a token of that word refers to a group that contains the speaker, and so on and so forth.) Second, even if indexicality speaks against literalism, it is a quite restricted phenomenon: There are only a limited number of expressions that require contextual saturation, so the contextualist attack remains under control.In response, I pointed out that many expressions in need of contextual saturation are semantically under-specified rather than indexical in the narrow sense.Their content depends upon the context, but they are not ‘token-reflexive’.A good example of under-specification is the genitive construction, as in ‘John’s car’: this phrase refers to a car bearing a certain relationRto John, which relation is determined in context, without being linguistically specified.(It may be the car John bought, or the car he dreamt of last night, or anything.) The linguistic meaning of the construction does not encode a token-reflexive rule telling us how, for each particular token of the expression, we can determine the content carried by that token as a function of the circumstances of utterance.So it is not true that saturation is ‘governed by the conventions of the language’, in such a way that pragmatic inference might be dispensed with.As for the second tenet of the literalist defense—the fact that context-sensivity is a limited phenomenon corresponding to a particular class of expressions—it collapses as soon as one accepts pragmatic modulation as a possible determinant of truth-conditional content.For modulation itself is context-sensitive:Whetherornotmodulation comes into play, and if it does,whichmodulation operation takes place, is a matter of context.It follows that what an expression actually contributes to the thought expressed by the utterance in which it occurs isalwaysa matter of context.

Many people attacked contextualism on the grounds that it is incompatible with the project of constructing a systematic semantics for natural language—a project that has been remarkably successful thanks to the progress of formal semantics over the past thirty years.In my 2010 book,Truth-ConditionalPragmatics, I attempt to defend contextualism against this charge by showing there is no straightforward incompatibility between context-sensitivity and systematicity, and by sketching what a compositional pragmatics might be like.

3.SITUATIONS

Saturation and modulation are two families of pragmatic processes that are ‘primary’ in the sense that they affect what is said—the utterance’s intuitive truth-conditional content.Because of the role they play, the same sentence-type may be used to express different propositions in different contexts.But a proposition determines a truth-value only with respect to a ‘circumstance of evaluation’ (for example a world, or a world and a time, or a situation, depending on one’s semantic framework); and the circumstance with respect to which a given content is to be evaluated itself depends upon the context in which that content is expressed.This gives rise to a third type of context-sensitivity, to which I have devoted a number of studies since the mid-nineties (including a large part of my booksOratioObliqua,OratioRecta, 2000, andPerspectivalThought, 2007).

Consider the following example, from Barwise and Etchemendy (1987: 29).Commenting upon a poker game I am watching, I say:“Claire has a good hand.” What I say is true just in case Claire has a good hand at the moment of utterance.But suppose I made a mistake and Claire is not among the players in that game.Suppose further that, by coincidence, she happens to be playing bridge in some other part of town and has a good hand there.The proposition I express is the proposition that Claire has a good hand, andthatis true; still, intuitively, my utterance isnottrue, because the situation it is about (the poker game I am watching) is not one in which Claire has a good hand at the time of utterance.The utterance concerns a particular situation (the poker game I am watching) and the proposition it expresses is not truewithrespecttothatsituation.This arguably shows that an utterance’s intuitive truth-value depends upon two things: its semantic content, and the situation with respect to which that content is evaluated.The utterance is true iff the proposition it expresses is true with respect to the situation it concerns.Which situation that is is determined by the context, the interests of the speech participants, what they are talking about, etc.It corresponds to the ‘topic’ of the utterance in the traditional sense: That which the speaker is talking about.

The contextual determination of the relevant situation is neither saturation nor modulation.It is not saturation because there is no indexical or pronominal expression standing for the situation talked about.The situation talked about is not, or at least need not be, represented in the content of what we say.Rather, what we say—the semantic content of our utterance—is evaluated with respect to a contextually provided situation, which remains external to that content.Nor is the contextual provision of the situation talked about a matter of modulation.What undergoes contextual modulation is always the meaning of a particular expression in the sentence, and here it is the content of the whole sentence which is globally taken to concern a particular situation.

The distinction between ‘content’ and ‘circumstance of evaluation’ is old in the philosophy of language (see in particular Kaplan 1989; Lewis 1980).In modal logic, propositions are evaluated relative to possible worlds.A proposition may be true relative to a world w, and false relative to another world w’.A proposition whose truth-value varies across worlds is said to becontingent(as opposed tonecessary).Similarly, in tense logic, propositions are evaluated relative to times.A proposition (e.g.the proposition that Socrates is sitting) may be true relative to a time t, and false relative to another time t’.A proposition that has this property is said to betemporal(as opposed toeternal).For various purposes, the circumstance of evaluation has been enriched with even more ‘coordinates’ than a world and a time.In his work on ‘attitudesdese’, David Lewis has suggested that the circumstance of evaluation should include an individual in addition to a time and a world, in order to capture the egocentric perspective of the subject of thought (Lewis 1979).Similarly, it has been proposed that the circumstance of evaluation should include normative standards (e.g.standards of taste) to account for evaluative propositions such as the proposition that spinach is delicious.(According to the ‘semantic relativists’, that proposition is true relative to some standards of taste, and false relative to others.See Kölbel and Carpintero 2008 for a survey.)

On the canonical picture of content we inherited from Frege, these ‘relativized propositions’ (temporal propositions, evaluative propositions, etc.) are not genuine propositions.Genuine propositions are supposed to be true or false.But the proposition that Socrates is sitting (or the proposition that spinach is delicious) is not evaluable as true or false, or at least, it is not evaluableunlesswe are given a further ingredient—a particular time, or a particular standard of taste, relative to which the content can be evaluated.Let us focus on the temporal example to make the general point.In the absence of a time specification, the ‘proposition’ that Socrates is sitting is only ‘true-at’ certain times and ‘false-at’ others.It is not true or false absolutely.It is, therefore, not a genuine proposition (thought) by Frege’s lights:

A thought is not true at one time and false at another, but it is either true or false, tertium non datur.The false appearance that a thought can be true at one time and false at another arises from an incomplete expression.A complete proposition or expression of a thought must also contain a time datum.(Frege 1967: 338, cited in Evans 1985: 350)

As Evans points out, the problem of incompleteness does not arise in the modal case.Even if a thought is said to be ‘true-at’ one world and ‘false-at’ another, as in modal logic, this does not prevent it from being true (or false)toutcourt.It is truetoutcourtiff it is true-at the actual world.But the ‘thought’ that Socrates is sitting cannot be evaluated as true or falsetoutcourt.In the absence of a contextually supplied time it canonlybe ascribed relative, ‘truth-at’-conditions.Only a particular, dated utterance of such a sentence can be endowed with genuine truth-conditions.What this shows, according to Frege, is that the time of utterance is a constitutive part of the ‘hybrid symbol’ of which the sentence uttered at that time is another part.What expresses a complete content (a genuine proposition) is not the sentence “Socrates is sitting”by itself, but the hybrid symbol, that is, the sentence in conjunction with a particular time of utterance.

Let us grant Frege that the complete content of the utterance “Socrates is sitting” involves more than the ‘temporal proposition’ expressed by the sentence (a proposition that can only be evaluated relative to particular times, but not absolutely); it additionally involves the time of utterance, which is tacitly referred to.This is compatible with the content/circumstance distinction, provided we draw a further distinction between two notions of content—explicit content and complete content.In our example, the time of utterance, which features in the circumstance of evaluation, is constitutive of thecompletecontent of the utterance, but it remains external to the ‘explicit’ content of the utterance, that is, the content expressed by the sentence itself.In this framework, the complete content of an utterance consists of two things: the explicit content, and the circumstance with respect to which we evaluate that content.Once it is admitted that we need these two components, we can tolerate explicit contents that are not semantically complete in Frege’s sense, i.e.endowed with absolute truth-conditions.We can, because the circumstance is there which enables the content to be suitably completed.Thus the content of tensed sentences is semantically incomplete, yet the circumstance (the time) relative to which such a sentence is evaluated is sufficient to complete it.The same thing holds for evaluative propositions, or for Lewis’sdesecontents.

In the Barwise-Etchemendy example, the explicit content is the proposition that Claire has a good hand.This is evaluated with respect to a circumstance involving not only a particular time (the time of utterance) but also a particular situation at that time: The poker game the speaker and his addressee are watching.The two levels of content enable us to account for our conflicting intuitions: what the speaker says (viz., that Claire has a good hand) is true, since Claire happens to have a good hand where she is; yet the utterance as a whole isnottrue, because the situation it is about (the poker game the speaker is watching) is not one in which Claire has a good hand.

On this picture, the context plays two roles: Through saturation and modulation, it contributes to determining the proposition expressed by the uttered sentence—its explicit content; but it also determines the circumstance with respect to which that content is to be evaluated.Like modulation and unlike indexicality, this third form of context-dependence, which we may call ‘circumstance-relativity’, is not tied to a particular class of expressions; it is ageneralfeature of language use.It is, therefore, relevant to one of the main questions at issue in the literalism/contextualism debate: How generalized is context-dependence? My claim is that,wheneverwe say something, what we say concerns a particular situation that we are attempting to characterize, and which the context indicates.The utterance is true if the situation corresponds to the way we characterize it.That means that the same content may be evaluated as true or false depending on the situation we take to be contextually relevant for its evaluation.This, again, is a general feature which applies to every utterance, whether or not it involves indexicals or other expressions in need of contextual saturation.

4.FROM LANGUAGE TO THOUGHT

The subtitle of my bookDirectReferenceis: “From language to thought”.One of my central concerns over the past fifteen years has been to extend to representation in general, and to mental representation in particular, some of the lessons we learn from the study of linguistic representations.

When we move from language to thought, the role of context seems to be more widely accepted, as if ‘literalism’ was out of place in this area.The majority view has it that no content is wholly independent of context: The content of mental representations essentially depends upon the environment.Thus ‘externalism’ is the dominant position in the philosophy of mind, while contextualism remains a minority position in the philosophy of language.

Yet the contrast should not be overestimated.The sort of context-dependence that externalism generalizes is rather trivial.It is the content of mental representation-typesthat is said to depend upon the environment—e.g.the environment in which the species has evolved, or the environment in which the concepts whose content is at issue have been acquired.As I wrote inDirectReference,

Mental contents are (...) environment-dependent in the sense that the existence of a certain type of content depends on there being systematic causal relations between states of the mind/brain and types of objects in the external world.Thus a (type of) configuration in the brain is a concept of water only if it is normally tokened in the presence of water.It follows that there would be no water-concept if there were no water.This sort of environment-dependence is what Externalism is concerned with.It affects mental states considered as types: The content of a mental statetypedepends on the environment—namely, on what normally causes a tokening of the type.(Recanati 1993: 214-15)

It is quite obvious that the same ‘syntactic’ configuration in the brain would have a different content, or no content at all, if it was found elsewhere than in the brain of organisms with a certain habitat and a certain history of living in that habitat.The form of context-dependence that externalism generalizes is comparable to a trivial form of context-dependence which can be found on the language side and which Bar-Hillel talks about in the following passage:

Let me (...) mention a brand of dependency which embraces even the non-indexical sentences.I mean the fact that any token has to be understood to belong to a certain language.When somebody hears somebody else utter a sound which sounds to him like the English ‘nine’, he might sometimes have good reasons to believe that this sound does not refer to the number nine, and this in the case that he will have good reasons to assume that this sound belongs to the German language, in which case it refers to the same as the English ‘no’.In this sense, no linguistic expression is completely independent of the pragmatic context.But just because this kind of dependence is universal, it is trivial, and we shall forget it for our purposes.(Bar-Hillel 1954/1970: 80)

Being comparable to the trivial generalization of context-dependence Bar-Hillel talks about, the generalization of context-dependence advocated by externalism is quite different from that advocated by contextualism in the language case.This raises the following question: Are there, in the mental realm, forms of context-dependence that are similar to the forms of context-dependence at issue in the literalism/contextualism debate?

In the same passage fromDirectReferencewhich I quoted above, I mention

another form of environment-dependence which affectstokensrather than types.The ‘wide’ content of a particular token of the thought “This man looks happy” is environment-dependent in the (stronger) sense that it depends on the context of occurrence of this token: It depends on the particular man who happens to causethistokeningof the thought.(Recanati 1993: 214-15)

Insofar as it affects the content carried by a particular token, rather than the constant meaning of the type, this form of context-dependence is similar to the dependence of the content of an indexical sentence upon the context of utterance.Indeed the dependence of the ‘wide’ content of a thought upon the context of thinking is sometimes referred to as ‘mental indexicality’; a label that is motivated, in part, by the fact that the thoughts whose content is dependent upon the context in this way are typically expressed by indexical sentences such as “This man looks happy” or “I am hot”.

Thanks to the work of Perry and others, it is generally acknowledged that there are thoughts whose truth-conditional content depends upon the context, just as there are sentences whose truth-conditional content depends upon the context.What remains controversial, however, is the idea that the thoughts whose truth-conditional content depends upon the context are like mental sentences that contain indexical vocabulary items (concepts) whose function is similar to that of indexical words.On this view, there is a ‘concept of self’ that is the mental counterpart of the word ‘I’.When Castor and Pollux both think “I am hot”, they entertain distinct thoughts by Frege’s lights, since the truth-conditions of the thoughts differ (one is true just in case Castor is hot, the other just in case Pollux is hot).Different though they are, the two thoughts share the same vehicle, and that is where we find the concept of self.Both Castor’s thought and Pollux’s thought involve that concept construed as the mental vehicle through which one refers to oneself.Just as the word ‘I’ refers to distinct individuals and therefore acquires a different sense (content) in different contexts, the mental ‘I’ also refers to distinct individuals and acquires a different content in different contexts.

This view has been elaborated by John Perry, among others (Perry 1993).Perry uses Kaplan’s content/character distinction and applies it to the analysis of thought.The thought-vehicle is a mental state whose constant meaning or ‘role’ is or determines a function from contexts to contents.In context the vehicle carries a content that is what the subject assents to or dissents from.But the subject’s assent or dissent depends upon the vehicle.One may assent to a certain content when that content is carried by a certain vehicle (e.g.‘I am French’) and not when it is carried by a distinct vehicle (‘Recanati is French’).Same content, different vehicles, different behaviours.In the other direction, the fact that Castor and Pollux use the same vehicle—are in the same state—is indicated by their common behaviour: When they think “I am hot”, they both take off their sweater or open the window, or do something like that.Different contents, same vehicle, same (type of) behaviour.(See Perry 1977)

That is not the only possible way of dealing with mental indexicality, however.Another way of dealing with it, advocated by David Lewis (1979), appeals to what I called ‘circumstance-relativity’.Circumstance-relativity yields truth-conditional differences that cannot be traced to the representational vehicle.The same sentence “It is raining” expresses different propositions in different contexts not because it is ambiguous or involves hidden indexicals, but because the (explicit) content that is expressed by that sentence is evaluated with respect to varying circumstances.What is contextually variable, in this sort of case, is the circumstance, not the content we evaluate; but the complete truth-conditional content of the utterance involves the circumstance as well as the explicit content: The utterance is true iff its (explicit) content is true with respect to the relevant circumstance.If we change the circumstance of evaluation, we change the overall truth-conditions.

According to David Lewis, thoughts that we would express by using indexical sentences are actually best handled in terms of circumstance-relativity.For Lewis, there is a thought content (not merely a ‘vehicle’) which Castor and Pollux share when they both think “I am hot”; but that content is not a classical proposition.Rather than a classical proposition, true at some worlds and false at others, the common content of their respective thoughts isthepropertyofbeinghot, which Castor and Pollux each self-ascribes.Rather than draw a distinction between the vehicle (or character) and the content of their beliefs, as Perry does, Lewis thinks we need to relativize the truth of what they think to the right sort of circumstance.In the case of belief and other attitudes, the circumstance of evaluation isaworldcenteredonthebelieveratthetimeofbelief, and the explicit content of the attitudes, to be evaluated with respect to the believer’s centered world, is a property rather than a classical proposition.To believe something is, for Lewis, always to self-ascribe a property, e.g.the property of being hot, or the property of living in a world in which Frege died in 1925.In this framework indexical belief falls out as a particular case.

In my own work, I have pursued both directions of research and tried to integrate them within a unified picture.InPerspectivalThought, following Lewis, I appeal to circumstance-relativity to model the egocentric content of experiential states.But I don’t think we have to give up the standard treatment of mental indexicals à la Perry.InDirectReferenceand in a forthcoming book,MentalFiles, I try to give substance to the idea that we refer to objects through mental files which themselves work like indexicals.On the general picture I advocate, there is both mental indexicalityandcircumstance-relativity.

5.MENTAL FILES

Imagine a subject who entertains the thought “This man looks happy” while having a certain visual experience.Let’s suppose the man he perceives is Bob.Since Bob is mentally referred to, the thought’s truth will arguably depend upon Bob’s properties: It will depend upon whether Bob (is a man and) looks happy.Had the context been different, the man whom the subject perceives would have been someone else—say Bill.Then Bill would have been referred to, and the thought’s truth-conditions would involve Bill.That is so even if we suppose that no qualitative change occurs in the subject’s visual experience from one context to the next: The thought that is expressed changes purely as a result of an external change in the context.One thought is true iff Bob (is a man and) looks happy, the other is true if and only if Bill (is a man and) looks happy.Since one thought could be true and the other false, this is sufficient to show that the two thoughts are distinct, by Fregean standards.(For Frege, two thoughts are distinct if they can take different truth-values.) In the vehicle sense, however, the thoughts are arguably the same: internally, the subject’s state of mind is the same.In both cases he thinks “This man looks happy” while having a visual experience that is qualitatively identical in the two cases.This is similar to the subject’ssaying“This man looks happy” twice and thereby expressing distinct Fregean thoughts simply because the context, hence the referent of the demonstrative, has changed from one occurrence to the next.

In a series of studies I tried to account for indexical reference in thought in terms ofmentalfiles.Mental files are based on contextual relations to objects in the environment; different types of files correspond to different types of relation.The characteristic feature of the relations on which mental files are based is that they areepistemicallyrewarding(hence my name for them: ER relations).They enable the subject to gain information from the objects to which he stands in these relations.The role of the file is to store information about these objects—information that is made available through the relations in question.So mental files are ‘about objects’: Like singular terms in the language, they refer, or are supposed to refer.They are, indeed, the mental counterparts of singular terms.What they refer to is not determined by properties which the subject takes the referent to have (i.e.by information—or misinformation—inthe file), but in externalist fashion, through the subject’s ER relations to various entities in the environment in which the file fulfills its function.The information (or misinformation) in the file therefore corresponds to the properties which the subject takes the referent to have, but these properties are not what determines the reference of the file.What determines the reference of the file is the ER relation on which the file is based.

In the above example (“This man looks happy”) the relevant mental file is a demonstrative file based on a perceptual/attentional relation to the object of thought.This is a temporary file that exists only as long as the subject is able to focus his or her attention on the object given in perception.In general, the contextual relations to objects which indexical reference exploits are short-term relations to the referent.Thus typical indexical concepts like HERE or NOW are temporary mental files based on short-lived ER relations to the place we are in, or to the current time, which relations enable the subject to know (by using his senses) what is going on at the place or time in question.There are exceptions, though.According to Perry (2002), the SELF file is astablefile based upon a special relation which every individual permanently bears to himself or herself, namely identity.In virtue ofbeinga certain individual, I am in a position to gain information concerning that individual in all sorts of ways in which I can gain information about no one else, e.g.through proprioception and kinaesthesis.The mental file SELF serves as a repository for information gained in this way.[注]As we shall see in due course, this is not the only sort of information about oneself that can go into the file.A file based on a certain ER relation contains two sorts of information: information gained in the special way that goes with that relation (first-person information, in the case of the SELF file), and information not gained in this way but concerning the same individual as information gained in that way.Other stable files include recognitional files (based upon lasting dispositions to recognize the object), files based on testimonial relations to objects we hear about in communication, and ‘encyclopedia entries’, that is, detached files based on higher-order ER relations which abstract from specific information channels.InMentalFilesI argue that the ‘indexical model’ applies to all these files, however stable they are.

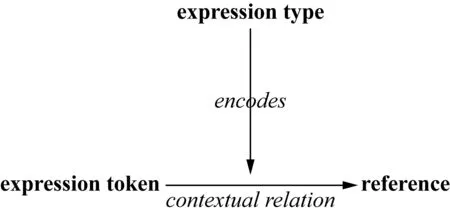

As far as linguistic indexicals are concerned, the critical features seem to me to be the following:

(1) There aretwosemanticdimensions, corresponding to character and content, or to standing meaning and reference, and they map onto the type/token distinction.

(2) Reference is determined throughcontextualrelationsto the token (hence indexicals are context-sensitive).

(3) The standing meaning is ‘token-reflexive’—it reflects the relation between token and referent.

Figure 1 below sums up the standard story regarding indexicals:

Figure 1 The Indexical Model for Language

This model, I argue, applies to thought.To be sure, the notion of conventional meaning does not apply in the mental realm, but the type/token distinction does apply.As far as mental files are concerned, they are typed according to the type of ER relation they exploit.Thus the SELF file exploits the relation in virtue of which one can gain information about oneself in a way in which one can gain information about no one else (as Frege puts it).My SELF file is not the same as yours, and they refer to different persons, of course, but they belong to the same type: They are both SELF files, unified by the common ER relation which is their function to exploit.We see that thefunctionof files—namely, informational exploitation of the relevant ER relation—plays the same role as the conventional meaning of indexicals: Through their functional role, mental file types map to types of ER relations, just as, through their linguistic meaning (their character), indexical types map to types of contextual relation between token and referent.The indexical model therefore applies to mental files, modulo the substitution of functional role for linguistic meaning (Figure 2).

Figure 2 The Indexical Model for Thought

If I am right, then there are ‘mental indexicals’, as Perry claimed.But there is room also for circumstance-relativity in thought, as Lewis claimed.To this (last) issue I now turn.

6.IMPLICIT REPRESENTATION

In the language case I have drawn a distinction between the explicit content of an utterance and the complete content which involves a situation of evaluation in addition to the explicit content.In the mental case, the mode/content distinction introduces something very similar, or so I claimed.

What—following Searle (1983)—I call the ‘mode’ is what enables us to classify experiential states into types such asperceptions,memories, etc., quite independent of the content of the state (what is perceived, remembered, etc.).InPerspectivalThought, I argue that the mode determines the situation with respect to which the content of an experiential state is to be evaluated.Since the mode contributes in this way to the state’s complete content, the explicit content of the state need not possess absolute truth-conditions.InPerspectivalThought, indeed, I argue that the content of perception is a temporal proposition, true at certain times but not at others.That is so because the content of a perception is to be evaluated with respect to the situation of perception.The situation of perception includes the time of perception, and that is how the relevant time gets into the complete content: the perceptual state is veridical only if what the state represents is the caseatthetimeofperception.The time of the seeing is relevant to the evaluation of the visual experience, but it is not part of what is seen.

The situation of perception involves not only a specific time, relevant to the evaluation of what is perceived, but also a certain (causal-epistemic) relation between the perceiver and what is perceived.A perception cannot be veridical unless that relation obtains, yet the relation is no more part ofwhatis perceived than the time of perception is.The subject does not perceive that he perceives, though he is aware of it: He perceives an external state of affairs, and, simply in virtue of being in such a perceptual state, is justified in assuming that he stands in a certain causal-epistemic relation—the perceptual relation—to the state of affairs which the state represents.

On this picture, the complete content of the state is jointly determined by its (explicit) content and by its mode.The mode determines the situation with respect to which the content of the state is to be evaluated.In the case of perception, the content of the state is to be evaluated with respect to the situation of perception—a situation that is contemporaneous with the state, and which involves the subject of the state’s standing in a certain causal relation to what the state represents.So, when the subject sees Bill looking happy, Bill is explicitly represented, he is part of what is perceived broadly construed, while the time at which Bill looks happy is only implicitly represented, via the contribution of the perceptual mode.When, some time later, the subject remembers Bill looking happy, the content of his state is arguably the same, but the contribution of the mode is different.In the case of memory the mode determines that the content of the state is to be evaluated with respect to apastsituation of perception—a situation that isnotcontemporaneous with the state the remembering subject is in.So the temporal difference between perception and memory is not a difference in contentstrictosensu—a difference between what is perceived and what is remembered—but a difference in mode; a difference that affects thecompletecontent of the state, without affecting itsexplicitcontent.

The mode’s contribution to the complete content corresponds to what the experiential stateimplicitlyrepresents.Thus a perception of Bob’s looking happy implicitly represents the time at which Bob looks happy.When it comes to thoughts in the first person—attitudesdese, to use Lewis’s terminology—we can also distinguish between the subject’s implicit involvement arising from the experiential mode’s contribution to complete content, from the subject’s explicit self-identification in first-person judgments.

Consider the phenomenon of immunity to error through misidentification (IEM), to which I have devoted several pieces of work.If, without looking, the subject feels that his legs are crossed, the fact thathehimselfis the person whose legs are crossed is guaranteed by the fact that the information he gets about the position of his legs is gained ‘from inside’.I take the content of a proprioceptive experience to be nothing but a bodily condition; what makes the bodily condition in questionthesubject’sbodily condition is the mode of the experience—no information can be gained on the proprioceptive mode concerning the position of other people’s limbs.In other words, the mode imposes the subject of the state (at the time of the state) as the relevant circumstance of evaluation for the explicit content, namely the property of ‘having one’s legs crossed’ which is arguably the content of the proprioceptive state.No such thing happens when the subjectseesthe position of his limbs in the mirror; for the perceptual mode does not guarantee that the person whose limbs are seen is the subject.[注]What it guarantees, however, is that the person who sees is the subject, i.e.the person undergoing the visual experience.In this case, the subject has to explicitly identify himself as the person whose legs are crossed, and this gives rise to the possibility of ‘error through misidentification’.

In this framework, as I said above, there is both mental indexicality in the strict sense and circumstance-relativity.There is mental indexicality in the strict sense when, on the side of explicit content, we find a concept of self through which the subject explicitly identifies himself as the bearer of this or that property.That is what, inPerspectivalThought, I call an ‘explicitdesethought’.For example, when I think that I was born in 1952, I explicitly identify myself.That must be so because there is no way in which I could acquire this piece of information ‘from inside’.The self’s involvement cannot come from the mode, in such cases, hence it must come from the content.When information about the position of one’s limbs is at issue, the situation is different: Such information can be gained from inside, and if it is, the subject’s involvement may be left implicit and determined by the experiential mode.It need not be left implicit, though: The subject may explicitly self-ascribe the bodily condition that is the content of his proprioceptive state.It follows that there are two types of explicitdesethoughts (Recanati forthcomingb): Those which display immunity to error through misidentification because the mode of the underlying experience is what justifies self-ascribing the predicated property, and those which are not so immune because the subject’s information about the position of his or her limbs is not gained from inside.The difference between the two cases corresponds to a difference in the subject’s grounds for his self-ascriptive judgment.

What is it for the subject to explicitly think about oneself? It is to activate the SELF file.The SELF file is based on the first-person way of gaining information, but it is crucial that it can also be exercised in connection with information gained in another way.Mental files are concepts, and concepts satisfy what Evans calls the Generality Constraint:

If a subject can be credited with the thought thataisF, then he must have the conceptual resources for entertaining the thought thataisG, for every property of beingGof which he has a conception.This is the condition that I call ‘The Generality Constraint’.(Evans 1982: 104)

Translated into mental-file talk, the Generality Constraint says that a file should be hospitable to any information about the reference of the file, whether or not that piece of information is gained in the special way corresponding to the ER relation on which the file is based.Now the SELF file is based on the first-person way of gaining information and there is much information about myself that I cannot gain in this way.My date of birth is something I learn through communication, in the same way in which I learn my parents’ birthdates.In virtue of the Generality Constraint, it should be possible for that information to go into my SELF file.It follows that a file based on a certain ER relation contains two sorts of information: information gained in the special way that goes with that relation (first-person information, in the case of the SELF file), and information not gained in this way butconcerningthesameindividualasinformationgainedinthatway.Information about my birthdate is a case in point: I gain that information in a third-person way, through communication (as I might come to know anybody’s birthdate), but I take that piece of information to concern the same person about whom I also have direct first-person information, i.e.myself; so that information, too, goes into the SELF file.I am therefore able to exercise my SELF concept in thinking “I was born in 1952”.That information can go into the file because the file is ‘linked’ to other files based upon distinct ER relations.Whenever two files are linked, information from one file can flow freely into the other.(In the mental-file framework, identity judgments are accounted for in terms of linking between files.)

It is because of that dual aspect of the SELF conceptquasatisfier of the Generality Constraint that there are two types of explicitdesethoughts: Those that are, and those that are not, immune to error through misidentification.When some information is gained from inside, that is, in virtue of the ER relation on which the SELF file is based, that information can only be about the subject: The way the information is gained determines in which file it goes.As a result, as Evans puts it,“there just does not appear to be a gap between the subject’s having information (or appearing to have information), in the appropriate way, that the property of beingFis instantiated, and his having information (or appearing to have information) thatheisF”(Evans 1982: 221).But when some information about ourselves is gained from outside, through linking, it goes into the SELF file only in virtue of a judgment of identity.The thought “I was born in 1952”can thus be seen as the product of two thoughts: the thought that a certain person, namely the person I hear about in a given episode of communication, was born in 1952, and the thought that I am the person talked about.The thought that I was born in 1952 thus turns out to be ‘identification-dependent’, in Evans terminology, and vulnerable to error through misidentification.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to Prof.Longgen Liu, Prof.Feng Yang, and Yuhuan Suo for suggesting that I should write a general review of my research in the philosophy of language forContemporaryForeignLanguagesStudies.I am especially indebted to Prof.Longgen Liu for making my booksLiteralMeaningandTruth-ConditionalPragmaticsavailable in translation to Chinese readers.Some of the research reported in this paper has received funding from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme FP7/2007-2013 under grant agreement n° FP7-238128 and ERC grant agreement n° 229441—CCC.

REFERENCES

Austin,J.1975.HowtoDoThingswithWords(2ndedition).Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Bach,K.andHarnish,M.1979.LinguisticCommunicationandSpeechActs.Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Bar-Hillel,Y.1954.IndexicalExpressions.Reprinted in Bar-Hillel, 1970, pp.69-88.

Bar-Hillel,Y.1970.AspectsofLanguage.Jerusalem: The Magnes Press.

Barwise,J.andJ.Etchemendy.1987.TheLiar.New York: Oxford University Press.

Evans,G.1982.TheVarietiesofReference(edited by J.McDowell).Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Evans,G.1985.‘Does Tense Logic Rest on a Mistake?’ in G.Evans (ed.):CollectedPapers.Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp.343-63.

Frege,G.1967.KleineSchriften(edited by I.Angelelli).Hildesheim: Olms.

Grice,P.1957.‘Meaning,’PhilosophicalReview66: 377-88.

Grice,P.1989.StudiesintheWayofWords.Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Kaplan,D.1989.‘Demonstratives’ in J.Almog, H.Wettstein and J.Perry (eds.):ThemesfromKaplan.New York: Oxford University Press, pp.481-563.

Kölbel,M.andM.Garcia-Carpintero(eds.).2008.RelativeTruth.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lewis,D.1979.‘AttitudesDeDictoandDeSe,’PhilosophicalReview88: 513-43.

Lewis,D.1980.‘Index, Context, and Content’ in S.Kanger and S.Öhman (eds.):PhilosophyandGrammar.Dordrecht: Reidel, pp.79-100.

Malinowski,B.1923.‘The Problem of Meaning in Primitive Languages,’ supplement to C.Ogden and I.A.Richards,TheMeaningofMeaning(10thedition).London: Routledge, 1949, pp.296-336.

Perry,J.1977.‘Frege on Demonstratives,’PhilosophicalReview86: 474-97.Reprinted, with a postscript, in Perry, 1993, pp.3-32.

Perry,J.1993.TheProblemoftheEssentialIndexicalandOtherEssays.New York: Oxford University Press.

Perry,J.2002.Identity,PersonalIdentity,andtheSelf.Indianapolis: Hackett.

Recanati,F.1987.MeaningandForce.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Recanati,F.1989.‘The Pragmatics of What is Said,’MindandLanguage4: 295-329.Reprinted in Davis, S.(ed.):Pragmatics:AReader.Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991, pp.97-120.

Recanati,F.1993.DirectReference:FromLanguagetoThought.Oxford: Blackwell.

Recanati,F.2000.OratioObliqua,OratioRecta.Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press/Bradford Books.

Recanati,F.2004.LiteralMeaning.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Recanati,F.2007.PerspectivalThought.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Recanati,F.2010.Truth-ConditionalPragmatics.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Recanati,F.(forthcominga).MentalFiles.

Recanati,F.(forthcomingb).‘Immunity to error through misidentification: what it is and where it comes from’ in S.Prosser and F.Recanati (eds.):ImmunitytoErrorthroughMisidentification:NewEssays.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Searle,J.1969.SpeechActs.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Searle,J.1983.Intentionality.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sperber,D.andD.Wilson.1986.Relevance:CommunicationandCognition.Oxford: Blackwell.

Strawson,P.1964.IntentionandConventioninSpeechActs.Reprinted in Strawson,1971, pp.149-69.

Strawson,P.1971.Logico-LinguisticPapers.London: Methuen.

Tsohatzidis,S.(ed.) 1994.FoundationsofSpeechActTheory:PhilosophicalandLinguisticPerspectives.London: Routledge.