A Critical Review of Policies for Emission Reduction of Non-road Mobile Machinery*

2022-06-18XIEYixinFANHongqinHUANGZhenhua

XIE Yixin, FAN Hongqin, HUANG Zhenhua

(Department of Building and Real Estate, Faculty of Construction and Environment, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China)

Abstract:Increasing attention is being paid to the reduction of emissions from non-road mobile machinery, and many policies to promote the reduction have been established in countries and regions around the world, including the United States, Canada, the European Union, and China. This paper reviews these policies and analyzes two successful grant programs in the USA. Depending on the findings from the research, it is suggested that the Chinese government should tighten emission standards, introduce more financial subsidies, and strengthen supervision.

Keywords:non-road mobile machinery; policy analysis; emission reduction

0 Introduction

In recent years, the use of non-road mobile machinery (NRMM), such as construction equipment and agricultural machinery, has consumed large amounts of fossil fuels (e.g., gasoline and diesel) and emitted 18%~29% of CO, hydrocarbons (HC), NOx, and particulate matter (PM) from mobile sources in the world[1]. The European Environmental Agency published an emission inventory, pointing out that NRMM was a significant source of pollution in Europe[2]. NRMM will become a main mobile pollution source after 2030 and the largest source of CO and HC pollutants in Asia after 2050[1]. To reduce the extensive emissions from NRMM, international organizations and governments around the world, including the European Union (EU), the United States (USA), Canada, and Sweden, have initiated various emission standards[3]and economic incentives[4]to promote the reduction of emissions from NRMM. The policies have been proved effective to some degree. For example, the retrofitting of NRMM in Sweden has been mandatory since 2000, and thus NOxemissions throughout the country fell sharply from around 400 tons in 2000 to 100 tons in 2010[5].

According to a report from Ministry of Transport of the people’s Republic of China[6], there is an annual increase of 3 million new non-road diesel engines, and over 36 million tons of diesel fuels are consumed each year by NRMM on the Chinese mainland. To reduce NRMM emissions, the government has introduced a series of policies in recent years, such as theEmissionStandardsforNon-RoadMobileMachineryin 2014 and theTechnicalGuideonPollutionPreventionandControlofNon-RoadMobileMachineryin 2018. However, there are still many problems hindering the reduction of NRMM emissions in the current policies and systems, including the lack of a unified standard for existing NRMM, poor implementation, and inadequate supervision[6]. Also, in 2015, Hong Kong’s Environmental Protection Department (EPD) issued theRegulatoryControlonEmissionsfromNon-RoadMobileMachinery[7]. According to the database from EPD, there were over 50,000 registered NRMM holdings in China Hong Kong in 2021, with 20,000 labeled as approval and over 30,000 as exempt. The machines labeled as exempt still emit large amounts of air pollutants and are used on construction sites, at ports and airports, and often in urban living areas where the population is highly vulnerable to such pollution. However, Hong Kong government has not yet requested further improvements for the exempted NRMM that does not meet the emissions standard. It is therefore important to find ways to address the problems in China’s NRMM emission reduction policies by reviewing the experience in other countries and regions.

Therefore, this study investigates the management policies of NRMM emission reduction in developed countries to learn from their practical experience and then proposes related policies for China with the country’s legal and administrative regulations into consideration.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the research methodology including data collection; Section 3 summarizes the data collected and analyzes typical NRMM policies; Section 4 develops successful NRMM policy experience that can be applied in Chinese mainland and Hong Kong; Section 5 concludes the study.

1 Framework and methodology

1.1 Framework

The first step is to search for NRMM emission reduction policies from various sources so that the policies collected are comprehensive and current. The policies are then analyzed from two perspectives: a summary of overall characteristics and a content review of representative policies. Lessons and experience are extracted from the policy review and adapted in accordance with the existing NRMM emission reduction practices in the Chinese mainland and Hong Kong.

1.2 Data collection

The following specific websites are employed as data sources in this research to collect information on NRMM emission reduction policies: Transport Policy, Diesel Net, VERT, Diesel Technology Forum, MECA, and AECC[4,10-14]. These websites provide up-to-date, secure information on energy and environment-related policies, including NRMM emission reduction policies adopted by some countries, cities, and regions. In addition, we also search the official websites of the environmental protection departments and other related departments of the USA, the EU, Canada, Japan, Sweden, Germany, the Chinese mainland, India, Brazil, Mexico, California, Texas, Massachusetts, Connecticut, London, and Beijing. The key words selected to search for related information include “NRMM,” “off-road engine,” “reducing diesel emissions,” and “clean mobile source diesel.”

2 Results and analysis

2.1 Overview of NRMM emission reduction policies

From an analysis of the collected data, 144 policies are identified. The number of NRMM emission reduction policies is growing year by year. This indicates that importance has been attached to NRMM emission reduction by an ever-increasing number of countries and jurisdictions. About 81.94% of these NRMM emission reduction policies are mandatory and administrative, including relevant laws, regulations, and mandatory emission standards. In some air quality management laws, the work on NRMM emission reduction is considered conducive to air quality improvement. In other NRMM emission reduction regulations, more detailed requirements are articulated. The NRMM emission standards directly limit the emissions of different pollutants by volume from different types of NRMM. The implementation of emission reduction standards makes it illegal to operate NRMM failing to meet emission standards and drives the development and application of clean and advanced NRMM emission reduction technologies. The tightening of emission standards is one of the most effective measures to promote the reduction of NRMM emissions, and many countries, cities, and regions have already enacted their NRMM emission standards. The current NRMM emission standards worldwide are divided into Tiers 1~4 set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Stages I~V by the European Commission. Other countries and regions follow one or two of the standards to develop and revise their NRMM emission standards.

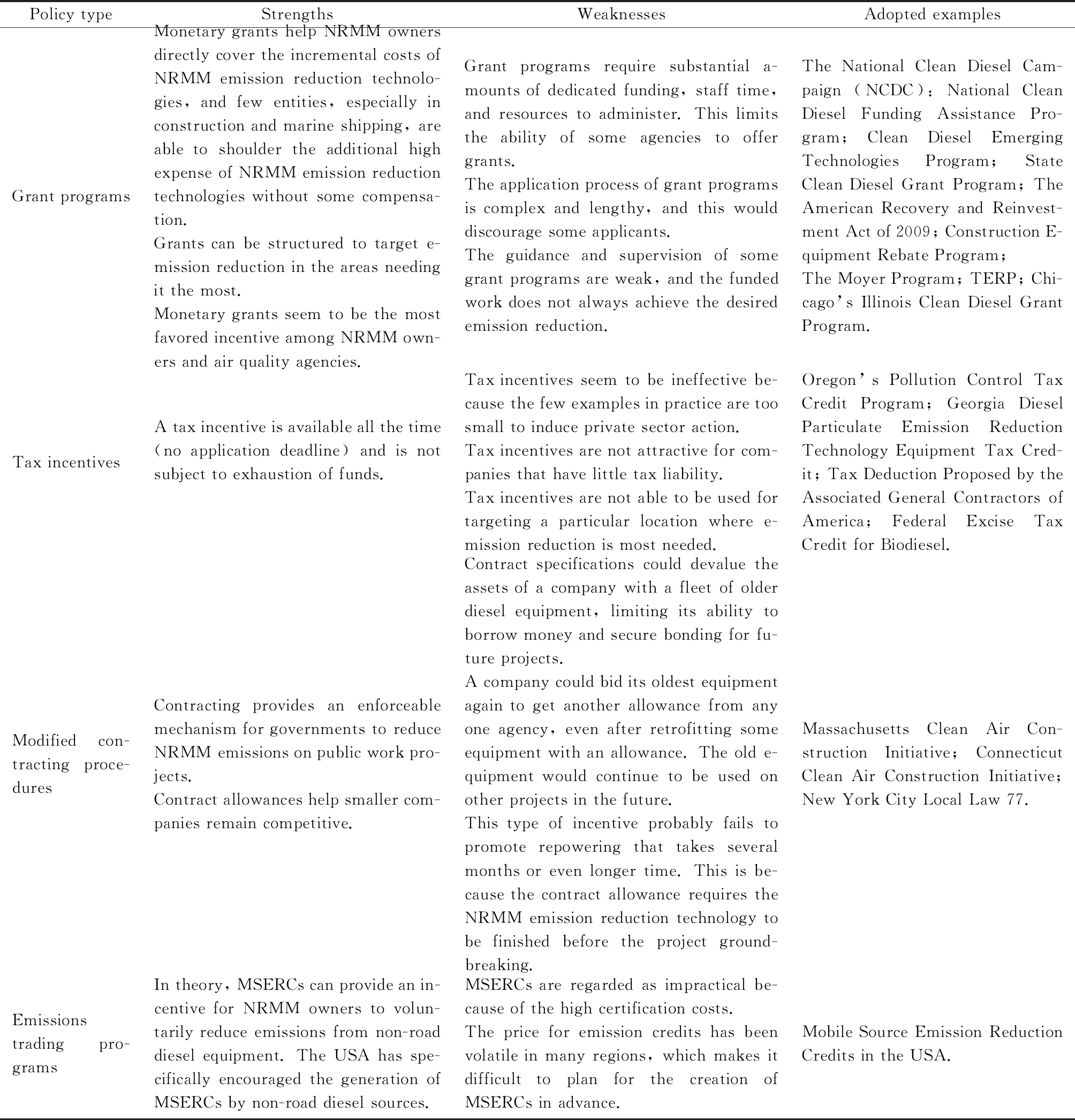

NRMM emission reduction policies include grant programs, tax incentives, modified contracting procedures, and emissions trading programs. According to reports from the EPA Office of Policy[15]and the EPA Office of Transportation and Air Quality[4], the strengths and weaknesses of incentive policies for NRMM emission reduction are summarized in Table 1. Specifically, the details of the incentives are as follows. (i) Grant programs provide funding directly to NRMM owners to help them purchase cleaner equipment, cleaner engines, or cleaner fuels and realize treatment retrofits. (ii) Tax incentives related to NRMM emission reduction comprise two types: tax deductions allow a taxpayer to reduce taxable income for certain expenses; while tax credits reduce tax liability for specific expenses. (iii) Modified contract procedures requiring NRMM emission reduction are more akin to regulations than to incentives and are often used in the construction industry. Contract provisions can take various forms, such as contract specifications stipulating emission reduction technology as part of a contract’s terms and conditions and a contract allowance which aims to help the winning bidder further reduce the emissions from NRMM used in the project. (iv) Emissions trading programs provide mobile source emission reduction credits (MSERCs) that can be traded between similar mobile sources. The owners of NRMM would voluntarily reduce emissions and then sell MSERCs. However, there are few examples of MSERCs in practice.

Table 1 Strengths and weaknesses of incentive policies for NRMM emission reduction

Financial grant programs tend to be the most effective in reducing NRMM emissions and are also the most favored incentive among NRMM owners and air quality agencies. Other types of incentives, such as taxes and emission credits, have few effective examples in practice. Policies promoting NRMM emission reduction over the last decade offer some valuable lessons for countries developing new incentive programs. Thus, two effective grant programs are analyzed in Section 3.2 below.

There are also some voluntary NRMM emission reduction policies, including voluntary emission standards issued by the USA and Japan, demonstration projects in the USA, and California’s certification and labeling. The role of these policies is often supplementary. Their number is small, and implementation is not frequent. Due to the lack of relevant information on such policies, their experience does not further form part of this study.

2.2 Typical grant programs for reducing NRMM emissions

Two highly successful statewide grant programs in the USA are the Carl Moyer Memorial Air Quality Standards Attainment Program (the Moyer Program) in California and the Texas Emissions Reduction Plan (TERP)[16-17]. The Moyer Program and TERP are selected in this review among grant programs for two main reasons. First, both programs have official reports that demonstrate their cost-effectiveness to control NRMM emissions. Second, compared to other grant programs, the two have available information on their process and post-implementation reports, which is useful for other countries to learn from.

2.2.1California’s Moyer Program

The Moyer Program was established in 1998 as a voluntary grant program that reduces air pollution from vehicles and equipment by providing incentive funds to purchase cleaner-than-required engines, equipment, and emission reduction technologies. The core principle of the Moyer Program is to achieve cost-effective emission reduction that is permanent, surplus, quantifiable, and enforceable. Covered pollutants include oxides of nitrogen (NOx), particulate matter (PM), and reactive organic gases ( ROG).

According to the Carl Moyer Program Statistics[18], the program provides about $60 million for projects each year statewide, which are funded through tire fees and smog impact vehicle registration fees. Considering the population, air quality, and other factors, California Air Resources Board (CARB) allocates funds to the air districts according to the statute. The air districts administer Moyer Program grants and select the projects to fund. The funds of the Moyer Program granted to applicants are based on the “incremental cost” of the equipment and the emission benefits of the project.

The Moyer Program has cost-effectively reduced smog-forming and toxic emissions in California. From its inception in 1998 to 2019, approximately $1.4 billion was allocated and the program’s “engine count” reached 67,924, including repowering, retrofits, scrap, new purchases, and vehicle/equipment replacements. Relying on the funding commitment, projects can achieve 7,156 tons of PM emission reduction and 194,514 tons of NOx+ ROG emission reduction. The regulatory, technological, and incentive landscapes have changed significantly since the creation of the Moyer Program.

2.2.2TERP

The TERP is administered by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ). It consists of several voluntary financial incentives and other assistance programs. These programs are expected to reduce NOxemissions in areas of the state that are close to violating the standard. Funding for TERP programs has been derived from a variety of tax surcharges and inspection fees and a portion of the state vehicle registration fee, in addition to new and increased sales and use surcharges.

TERP also encourages the development of new clean technologies as an incentive to develop new businesses and industries in Texas. Program funding was originally designed to be distributed among seven programs and administered by four state agencies and one state university research center. There are four main programs currently funded that are related to NRMM, including the Diesel Emissions Reduction Incentive (DERI) Program, the Emissions Reduction Incentive Grants (ERIG) Program, the Rebate Grants Program, and the Third-Party Grant Program. According to the TERP Biennial Report (2019-2020)[19], (i) since 2001, the DERI Program has provided $1,147,735,817 for 12,331 grant projects, and the projected NOxreduction has totaled 183,434 tons in DERI-eligible counties. The DERI program is the most cost-effective TERP program at an average cost of $6,257 per ton of NOxreduced. (ii) Since 2001, the ERIG Program has provided $871,398,686 in grants for 5,433 projects, with the projected NOxreduction totaling 151,092 tons at an average cost of $5,767 per ton of reduction. (iii) The Rebate Grants Program is based on pre-approved maximum rebate grant amounts for eligible on-road and non-road replacement and repowering projects. Since 2006, the Rebate Grants Program has provided $198,422,619 in grants for 3,077 projects whose projected NOxreduction has totaled 22,326 tons at an average cost of $8,888 per ton of NOxreduced. (iv) Since 2004, the Third-Party Grant Program has provided $65,489,149 in grants to 3,589 third-party sub-grant recipients, with the projected NOxreduction totaling 8,694 tons at an average cost of $7,532 per ton of NOxreduced. There are no current third-party grants in effect, although previous grantees are expected to continue to monitor the sub-grant projects over the life of those projects.

2.2.3Highlights of the two grant programs

According to the guideline of the Moyer Program (2017) and TERP (2020)[16-17], both have similar project procedures, including project solicitation, application review and selection, application-verification visits, grant and contract award, vehicle, equipment and engine verification, monitoring and reporting, and emission reduction commitments. Table 2 summarizes the highlights of the two grant programs from their guidelines.

Table 2 Highlights of the Moyer Program and TERP

3 Lessons or experience learned

3.1 Update existing NRMM emission standards in the Chinese Mainland and Hong Kong

The emission standards currently in force in the Chinese mainland and Hong Kong lag behind those in Europe and the USA. Thus, it is necessary to accelerate the preparation of emission standards for in-use NRMM and improve emission standards.

3.2 Grant incentives to reduce NRMM emissions

As the price of NRMM is relatively high, the residual value of old products is also relatively high. Local governments are encouraged to introduce subsidy policies to phase out NRMM of Tier 0, Tier 1, and Tier 2 emission standards in a categorized manner.

Funding for the Moyer Program is derived from tire fees and smog impact vehicle registration fees, and funding for the TERP programs comes from a variety of tax surcharges and inspection fees and a portion of the state vehicle registration fee, in addition to new and increased sales and use surcharges. Therefore, it is recommended that the funding source of the Chinese government for reducing NRMM emissions could also be from such fees and taxes.

There are also some compulsory requirements of the grants offered by the Moyer Program and TERP programs that guarantee their implementation, such as the setting of cost and effectiveness limits, location usage, activity life, and certification. The Chinese government can learn from these requirements.

3.3 Enhance supervision and monitoring

It is recommended that the government provides additional guidance and supervision to ensure that projects achieve their planned NRMM emission reduction, that activities are reported accurately, and that machinery is replaced in accordance with the grant awards of the country. Specifically, guidance and supervision procedures should include the followings: providing reasonable assurance that grantee progress reports are accurate and emission certification levels are verified, ensuring that grant and subgrant agreements specify the emission certification levels or years of new engines installed as part of vehicle replacement and engine repowering projects, issuing guidance clearly defining eligible costs for early replacements of vehicles and engines for the grants of the country, and recouping unsupported expenditures of funds.

4 Conclusion

Increasing attention is paid to the reduction of emissions from NRMM, and policies to promote the reduction have been established in many countries, cities, and regions. This study summarized these policies and reviewed two large-scale successful grant programs in the USA. It is suggested that in the Chinese mainland and Hong Kong, the government should update emission standards, introduce more financial subsidies, and enhance supervision.