Looking for positive viewpoints for Alzheimer’s caregivers: Case evaluation of a positive energy group

2016-07-12WenchienHsiehQinyingChenQinglingSunPeixuanChenYijiaChenWentingXuYitingZhangYiqianYuYimeiHuang

Wenchien Hsieh(✉), Qinying Chen, Qingling Sun, Peixuan Chen, Yijia Chen, Wenting Xu, Yiting Zhang, Yiqian Yu, Yimei Huang

Looking for positive viewpoints for Alzheimer’s caregivers: Case evaluation of a positive energy group

Wenchien Hsieh1,2(✉), Qinying Chen2, Qingling Sun2, Peixuan Chen2, Yijia Chen2, Wenting Xu2, Yiting Zhang2, Yiqian Yu2, Yimei Huang2

1Kaohsiung Municipal Ta‐Tung Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, China

2Department of Sociology and Social Work, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, China

ARTICLE INFO

Received: 17 December 2015

Revised: 18 February 2016

Accepted: 19 February 2016

© The authors 2016. This article is published with open access at www.TNCjournal.com

KEYWORDS

Alzheimer’s disease;

caregiver;

program design;

group activities;

interviews

ABSTRACT

Objective: As estimated in a report of global Alzheimer’s disease published by Alzheimer’s Disease International in 2015, there will be 9.9 million new patients worldwide with Alzheimer’s disease in 2015, with a new Alzheimer’s patient diagnosed, on average, every 3 seconds. Since Alzheimer’s disease is an irreversible disease, the most that can be done for Alzheimer’s patients is to merely delay the onset of disease, which to date cannot be completely cured. Therefore, even though great effort is put into caring for the patient, caregivers should not expect any substantial changes. The caring process is a dynamic process that contains negative and positive experiences. During the caring period, not only do caregivers spend a lot of effort and work very hard to help the patient, but in fact care recipients themselves also give energy to caregivers. This study attempts to take a positive energy viewpoint to explore and design a program that is suitable for Alzheimer’s caregivers. The aims of the study were as follows: (a) to explore the needs and burdens of Alzheimer’s caregivers in the treatment process of patients, (b) to design a program that meets the needs of the caregivers, and (c) to evaluate the effects of implementing a program.

Methods: The study is a qualitative study employing in‐depth interviews. Interviews were conducted from September 2015 to December 2015; the interview results were reviewed and a positive energy group program was designed. Pre‐test and post‐test interviews were carried out for the program so as to evaluate the effects of the program.

Results: According to the caregiver interview results, we understand the caring needs and caring process of caregivers. From the interview results, we now know that caregivers’ continuous care mainly comes from positive energy in psychological, social and relationship aspects. Positive energy seems to have been affecting caregivers’caring ability and willingness. Therefore, a two‐stage group activity program was designed to provide a recollective handmade craft group and an art therapy group. Research results of the study show that when the main caregivers of Alzheimer’s patients took part in group activities, positive energy in social and relationship aspects increased for the caregiver group too.

Conclusions: From these intervention programs caregivers could obtain more knowledge of patient care and these activities could effectively lighten caregivers’burdens.

Citation Hsieh WC, Chen QY, Sun QL, Chen PX, Chen YJ, Xu WT, Zhang YT, Yu YQ, Huang YM. Looking for positive viewpoints for Alzheimer’s caregivers: Case evaluation of a positive energy group. Transl. Neurosci. Clin. 2016, 2(1): 65–70.

✉ Corresponding author: Wenchien Hsieh, E-mail: 0986037@kmtth.org.tw

1 Case presentation

As estimated in a report of global Alzheimer’s disease published by Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI) in 2015, there will be 9.9 million new patients world‐wide suffering from Alzheimer’s disease in 2015, with an estimate of a new Alzheimer’s patient diagnosed on average every 3 seconds. In 2015 the number of people with Alzheimer’s disease in the world reached 46.8 million; it is estimated that in 2050 the figure will rise to 131.5 million. In Taiwan specifically, according to the population data and the results of the Taiwan Alzheimer’s disease epidemiological investigation at the end of June 2015, the total number of people living with Alzheimer’s disease in Taiwan was estimated to be 244,000, almost equivalent to the total population of Changhua City (235,000).

From these data, one can see that the number of Alzheimer’s patients has been increasing day‐by‐day. This also implies that the number of Alzheimer’s caregivers has been increasing as well. However, research mostly paid attention to the conditions of Alzheimer’s patients, but inadvertently neglected the physical and psychological burdens of Alzheimer’s caregivers. In fact, these caregivers are also a huge group of potential psychiatric patients, with needs, no less than Alzheimer’s patients themselves. Since Alzheimer’s disease is an irreversible disease, the most that can be done for Alzheimer’s patients is to merely delay the onset of disease, which cannot, to date, be completely cured. Therefore, even though great effort is put into caring for these patients, there may not be any significant improvements, contrary to what caregivers expect.

In the literature, Langer[1]indicated that the caring process included four main themes: families con‐fronting loss; discovery of turning points and understanding the change in the relationship with the aged; a sense of rediscovered self; and a sense of satisfaction and facilitation of the value of oneself. From this, one can see that the caring process is a dynamic process that contains both negative and positive experiences. During the caring period, not only do caregivers spend a lot of effort and work very hard, in fact, care recipients themselves also give energy to caregivers. This is an interacting process that gives caregivers satisfaction in caring. Caregivers’satisfaction in caring mainly comes from the interac‐tion between caregivers and care recipients. The two parties give energy to each other and this relationship is a dynamic process that can increase the positive outcomes[2–5]. Regarding this satisfaction in caring, there are many different terms and definitions, including positive aspects of caregiving, pleasure and reward of caregiving, enjoyment of caregiving, uplifts or daily events that evoke feeling of joy, gladness or satisfaction[5]. During the caring process, caregivers do not only have negative outcomes but positive ones too. If more positive outcomes are produced during the caring process, these can better alleviate the negative outcomes produced from the care work. These rewards and satisfactions derived from the caregiving relationship are commonly known as positive aspects of caregiving (PAC). The interaction between caregivers and care recipients facilitates family caregivers to feel satisfaction during caring. Such a dynamic relationship urges family caregivers to find benefits, thus eventually resulting in PAC. The factors that have been found to positively correlate with PAC include satisfaction from the earlier relationship with patients, satisfaction from social support, cognitive impairment of the care recipients, use of problem‐solving strategies, greater age of caregivers, and better physical conditions of caregivers[6]. The factors that affect the PAC in caregivers during the caring process include the seriousness of the patient’s disease (the higher the seriousness, the lower the PAC), the age of caregiver (the greater the caregiver’s age, the lower the PAC), and the economic and living conditions of the caregiver. The above factors have predictive power towards the PAC[7]. Nevertheless, PAC also affects the quality of life, the family life, the economic condition, the mental condition and overall health condition of the caregiver.

2 Purpose of the study

(1) To explore the needs and burdens of Alzheimer’s caregivers in the treatment process of patients.

(2) To design a program that meets the needs of caregivers.

(3) To evaluate the effects of implementing the program.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Research participants and study location

肾上腺是肝细胞癌(hepatocellular carcinoma,HCC)常见的转移部位,发生率约8%[1]。HCC的肾上腺转移瘤(adrenal metastasis,AM)合并下腔静脉癌栓(Inferior vena cava tumor thrombus,IVCTT)较为罕见。本文回顾性分析2例HCCAM伴IVCTT患者的临床资料,探讨其临床病理特点并提高诊疗认识。

The study adopted purposive sampling. The research locations, where study data was collected, were the Alzheimer’s Disease Clinic and the Neurological Examination Room of a district teaching hospital in Southern Taiwan.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria: Research participants had to be Alzheimer’s patients’ family members aged over 18, able to communicate with people verbally and in written‐form, and be the main caregivers of the Alzheimer’s patients during the period from con‐firmed diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease to subsequent treatment.

Recognition of main caregivers: Both parties, i.e., patients and caregivers, thought that the research target was the main caregiver.

3.2 Materials

The study was a qualitative study which employed in‐depth interviewing. After data collection took place from September 2015 to December 2015, we used the results of the caregiver interviews on caring needs and the caring process to design a program.

3.3 Editing of the interview outline

3.3.1 Basic particular form

Socio‐demographic information was collected and included: age, sex, education level, marital status, and religion and family structure of the caregiver and the care recipient.

3.3.2 Interview outline

The study mainly focused on the caregivers’ caring process (how they got along with patients, the caring situations, the changes of mood or thinking, the effects of caring for patients on the caregivers’ personal health conditions, and family life and work). Furthermore, the interviews also touched upon the caregivers’ needs.

4 Research results

4.1 Results of the caring process and caring needs obtained from the interviews

At the aforementioned study locations, caregivers were invited to take part in the study. After a clear verbal explanation of what the study entailed, it was ascertained that the caregivers had thoroughly understood the study procedure and their rights and interests, they were then asked to sign a consent form to show that they agreed to participate in the study. After this, in‐depth interviews were conducted. There were eight interview targets in the study. A qualitative survey was made for the interview contents, which are summarized in two parts (caregiver needs and positive energy of caring) as follows (Tables 1 and 2).

4.2 Evaluation of the effects of the program designed to lighten the burden for caregivers

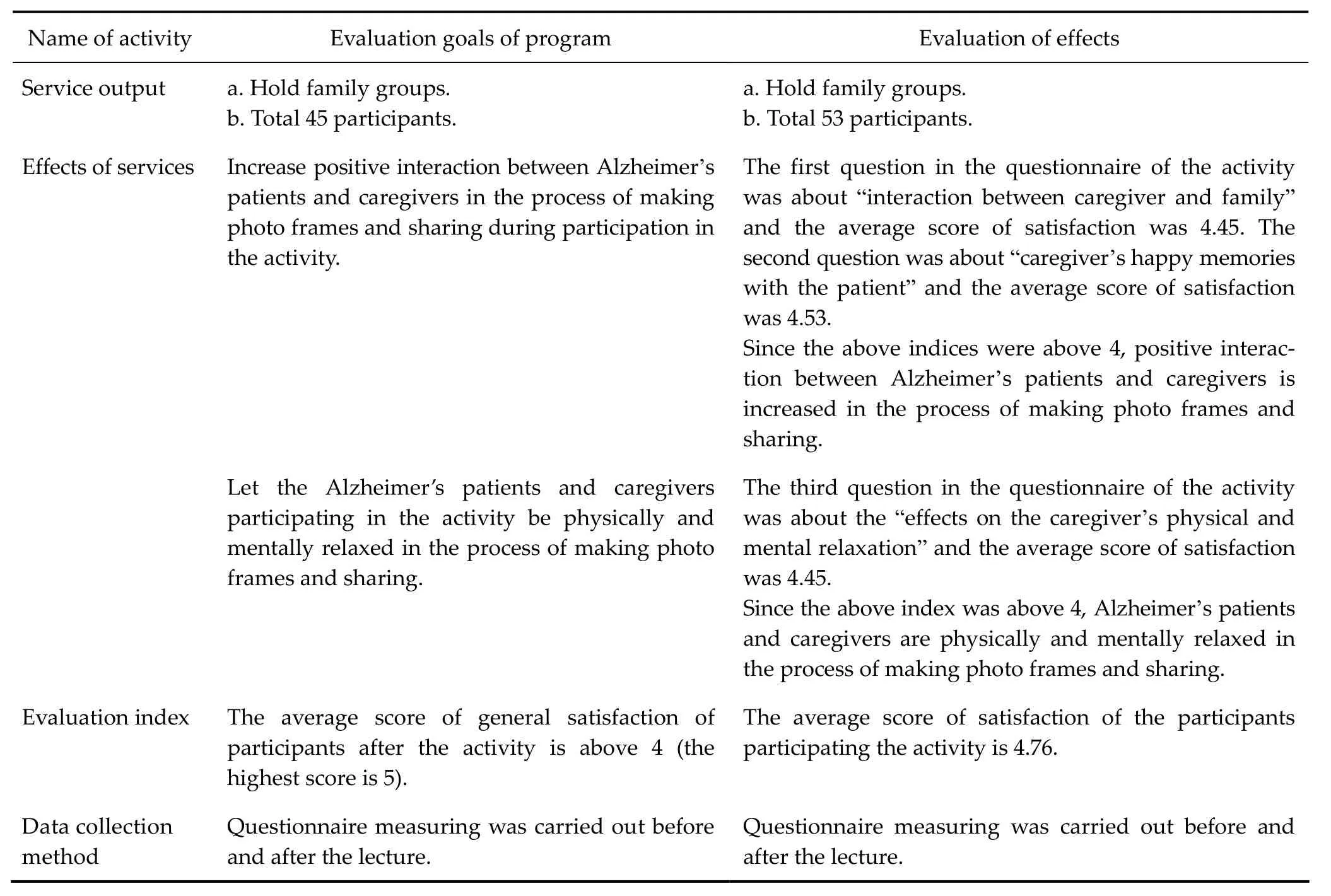

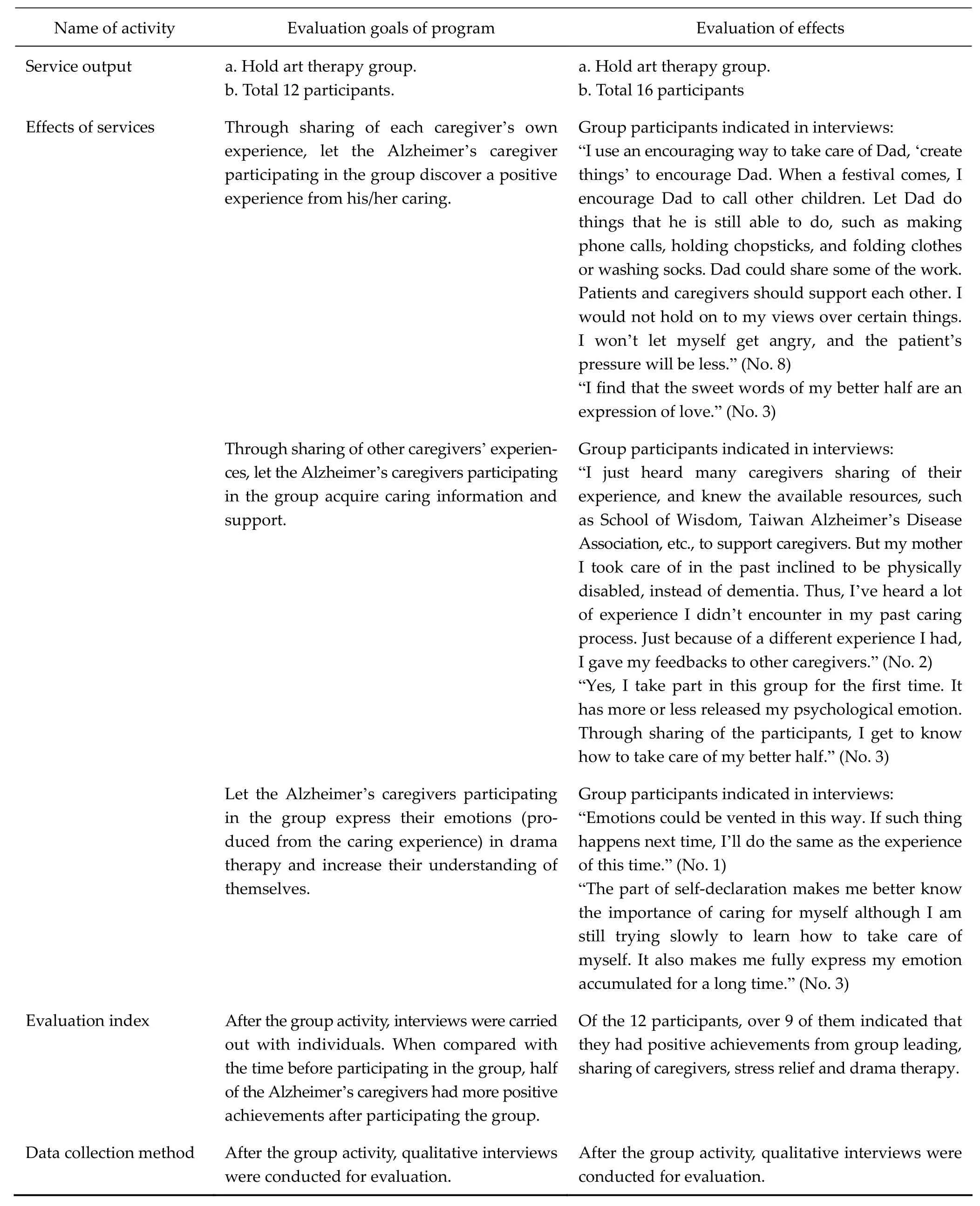

According to the results of the caring process and caring needs obtained from the interviews, two time frames of caregiver group program were designed, namely “Recollecting Past Fun—Handmade Craft Memory Group” and “Recollective Games—Art Therapy Group” (Tables 3 and 4). The purpose of the program was to promote positive interaction between Alzheimer’s patients and their caregivers, to increase the communication between Alzheimer’s patients and their caregivers, and to help caregivers discover positive power through the use of activities and take a positive viewpoint to their caring experience.

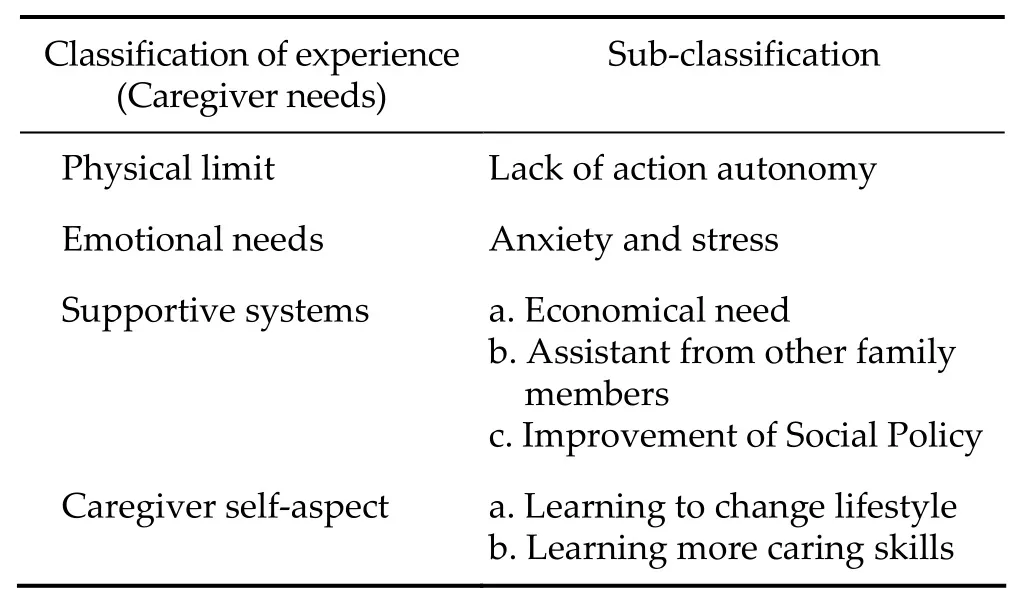

Table 1 Interview contents (caregiver needs)

Table 2 Interview contents (Positive energy of caring)

Table 3 Activity 1—Recollecting past fun‐handmade craft memory

Table 4 Activity 2—Recollective games: Art therapy group

5 Research value and clinical application

Most existing studies regarding family caregivers of Alzheimer’s patients focus on the burdens and the negative emotions that caregivers must face. However, as found in the qualitative interview survey of caregi‐vers’ needs, positive energy is really the important kinetic energy for families to keep on caring. The implementation process of the program further proves its suitability in meeting the caregivers’ needs and increasing positive energy. The results of the study can provide a reference for the future Alzheimer’s care system, which has its service model being currently designed. Presently, various assistance programs for caregivers have been providing support to families from “burden lightening” viewpoint. Nevertheless, we often neglect that if the banner of “burden” is hung up all the time, family members are left self‐pitying in their pessimistic and negative emotion. We should take another viewpoint to assist caregivers, and let the responsibility of caring be more meaningful. This study attempts to link the responsibility of caring to family love and dignity, and increase the depth of life of caring work.

As found in the results of this study and the activities program put in place, caregivers have a great need for medical information (caring knowledge and skills) and also the need for social aspect (group sharing). Such needs deeply affect caregivers’ energy levels, and could be a significant factor of influence on their quality of life. Therefore, in the future clinical caring system we can consider caregivers as assisted targets. Through the provision of caring information and skills, caregivers’ psychological burden and lack of medical knowledge can be improved. Focusing on the effects of treatment ways of the disease on quality of life, health education should be provided. Or, a coping strategy, with “cognition‐oriented” individual or group psychotherapy involved, can be adopted to actively improve individuals. Besides, the caregivers’satisfaction and feedbacks to the implemented program of the study’s activity clearly show that it is particularly important to give peer support to caregi‐vers, and let caregivers boost the morale of each other and give mutual encouragement. These are possible ways of supporting Alzheimer’s caregivers.

Conflict of interests

The authors have no financial interest to disclose regarding the article.

References

[1] Langer SR. Finding meaning in caring for elderly relatives: Lose and personal growth. Holistic Nurs Prac 1995, 9(3): 75–84.

[2] Boerner K, Schulz R, Horowitz A. Positive aspects of caregiving and adaptation to bereavement. Psychol Aging 2004, 19(4): 668–675.

[3] Cohen CA, Colantonio A, Vernich L. Positive aspects of caregiving: Rounding out the caregiver experience. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002, 17(2): 184–188.

[4] Nolan M, Grant G, Keady J. Understanding Family Care: A Multidimensional Model of Caring and Coping. Buckingham & Philadelphia: Open University Press, 1996.

[5] Tarlow BJ, Wisniewski SR, Belle SH, Rubert M, Ory MG, Gallagher-Thompson D. Positive aspects of caregiving: Contributions of the REACH project to the development of new measures for Alzheimer’s caregiving. Res Aging 2004, 26(4): 429–453.

[6] Tang ST, Liu TW, Lai MS, Liu LN, Chen CH. Concordance of preferences for end-of-life care between terminally ill cancer patients and their family caregivers in Taiwan. J Pain Symptom Manage 2005, 30(6): 510–518.

[7] Lopez SJ, Snyder CR. Positive Psychological Assessment: A Handbook of Models and Measures. Washington DC, USA: American Psychological Association, 2003, pp. 393–409.

猜你喜欢

杂志排行

Translational Neuroscience and Clinics的其它文章

- Malignant transformation and treatment of cystic mixed germ cell tumor

- Surgical complications secondary to decompressive craniectomy for patients with severe head trauma

- A new drainage tube device

- Effects of aging on working memory performance and prefrontal cortex activity: A time‐resolved spectroscopy study

- An association between the location of white matter changes and the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in Alzheimer’s disease patients

- Effects of regional cerebral blood flow perfusion on learning and memory function and its molecular mechanism in rats