季铵盐类消毒剂及大肠杆菌对其耐药性研究进展

2014-01-21邹立扣吴国艳何雪梅郭丽娟

邹立扣,吴国艳,2,程 琳,何雪梅,2,郭丽娟,2,龙 梅,2

季铵盐类消毒剂及大肠杆菌对其耐药性研究进展

邹立扣1,吴国艳1,2,程 琳1,何雪梅1,2,郭丽娟1,2,龙 梅1,2

(1.四川农业大学 都江堰校区微生物学实验室,四川 都江堰 611830;2.四川农业大学资源环境学院,四川 成都 611130)

研究表明,食源性细菌消毒剂耐药严重,大肠杆菌是食品污染状况及耐药性监测的指示菌,对季铵盐类消毒剂表现出比革兰氏阳性菌更强的抗性,且大肠杆菌对消毒剂与抗生素耐药性可共传播。鉴于此,本文综述了季铵盐类消毒剂的结构与种类、作用机制、大肠杆菌消毒剂耐药产生、耐药基因、基因型与表型的关系以及 与抗生素耐药共传播机制等的研究进展。食源性大肠杆菌对季铵盐类消毒剂抗性的耐药机制研究很少,研究大肠杆菌对季铵盐类消毒剂耐药性,可为消毒剂的规范使用以及食源性大肠杆菌的防控提供科学依据及理论基础。

大肠杆菌;季铵盐类;消毒剂;耐药

随着社会经济的发展与人民生活水平的提高,食品安全问题已经成为人们关注的焦点,而食品污染中致病微生物引起的食 源性疾病是影响食品安全的最主要因素之一[1-2]。大肠杆菌(Escherichia coli)被很多国家作为各类食品污染状况的指示菌进行检测,是保障食品安全的重要指标之一,其可导致腹泻,感染某些致病性较强的血清型时还可能致命,如O157∶H7引起的出血性腹泻和溶血性尿毒综合征(heomlytic uremic syndrome,HUS)等[3]。季铵盐类化合物(quaternary ammonium compounds,QACs)消毒剂常被用来防止食品工业中致病微生物的扩散及污染[4],可以有效减少食品中的病原微 生物,然而,抗菌药物的广泛或不合理使用可产生筛选压力,QACs消毒剂的使用会导致细菌的适应和耐药菌的生长,是消毒剂抗性增加的潜在动力[5]。目前,对革兰氏阳性细菌消毒剂耐药及耐药基因流行已有较多报道和研究,如葡萄球菌(Staphylococcus spp.)及肠球菌(Enterococcus spp.)等[6-8]。相对革兰氏阳性细菌,革兰氏阴性细菌对消毒剂表现出更强的抗性[9],但对革兰氏阴性细菌,特别是食源性革兰氏阴性细菌对QACs抗性的发生及耐药机制研究很少,全面调查大肠杆菌对QACs消毒剂耐药性已经迫在眉睫[10-11]。鉴于此,本文综述了季铵盐类消毒剂的结构与种类、作用机制、大肠杆菌消毒剂耐药产生、耐药基因、基因型与表型的关系以及与抗生素耐药共传播机制等研究进展。

1 食源性大肠杆菌简介

大肠杆菌是人和动物重要的共生肠道微生物,绝大部分大肠杆菌属于肠道正常菌群,但仍有部分菌株可导致人和动物感染、发病,这些致病性大肠杆菌可引起人类的肠胃炎、尿道感染、新生儿败血症或脑膜炎等。根据所含毒力因子的种类,致病性大肠杆菌可分为5 类,肠致病性大肠杆菌(enteropathogenic E. coli,EPEC)、肠产毒性大肠杆菌(enterotoxigenic E. coli,ETEC)、肠侵袭性大肠杆菌(enteroinvasive E. coli,EIEC)、肠黏附性大肠杆菌(enteroaggregative E. coli,EAEC)及肠出血性大肠杆菌(enterohemorrhagic E. coli,EHEC)等,这些大肠杆菌均可通过食物链进入人体并对人类的健康构成威胁[3]。食品中污染大肠杆菌主要发生在食品生产、处理、分配及零售等过程,20世纪以来,由于奶制品、水果、蔬菜、甜点、肉类及水产品等食品污染,引发了大肠杆菌的全球暴发,而暴发的场所有饭店、快餐店、自助餐厅、野餐、养老院及社区等[12]。除了具有较强的致病力,大肠杆菌可通过自身基因突变或捕获外源耐药基因产生耐药性,也可将耐药基因通过质粒及整合子等传递到在肠道或环境中与其共存的其他细菌,因此,被认为是耐药性监测中良好的指示菌,目前发现,众多食品特别是肉类食品中分离出的大肠杆菌抗生素耐药严重[13-14],是抗生素耐药大肠杆菌重要的“贮存库”[15-16],这些耐药菌可通过被污染的食品使人感染,对人类的健康构成威胁[17]。

2 季铵盐类消毒剂结构与种类

消毒剂是食品生产清洗、消毒过程中使用的主要化合物,可保证食品产品的微生物安全。为了避免在食品和普通消费者市场中微生物污染及感染的风险,消毒剂在共同卫生中使用正呈现增长的趋势,消毒剂中有众多的化学活性物质,主要用于消毒与保存。常用的消毒防腐剂有季胺盐类化合物、酚类化合物、双胍类、碘及其复合物、醛类、过氧化物和银化合物等,这些消毒剂有些已经使用了近百年,相对于抗生素,消毒剂可表现出更宽的广谱活性,且具有多个靶位点,而抗生素可能只有一个特异的胞内位点[18]。

在食品工业中,常规清洁和控制食品、环境中可产生严重疾病的病原微生物水平十分重要,清洁步骤中消毒剂的使用,可以减少表面微生物的生存[19-20]。QACs消毒剂由于具有无腐蚀、无刺激性、较稳定且毒性低等优点而被广泛地用于食品和环境的消毒[21-22]。QACs消毒剂亦被作为兽药控制动物疾病[23],使用QACs消毒剂可降低禽类养殖中细菌污染[24-25]。QACs包含一个4价氮, 基本化学结构为N+R1R2R3R4X-,其中R代表一个氢原子、一个烷基或烷基被替代的其他功能基团,X代表一个阴离子,比如氯或溴等[26](图1)。

图1 季铵盐类消毒剂结构通式[18]Fig.1 General chemical structur e of QACs[18]

美国国家环境保护局(U.S. Environmental Protection Agency,USEPA)把QACs分为四大类[27],而根据功能基团的不同,可分为三大类,具体见表1。

表1 QACs消毒剂的分类Table 1 Classification of QAC disinfectants

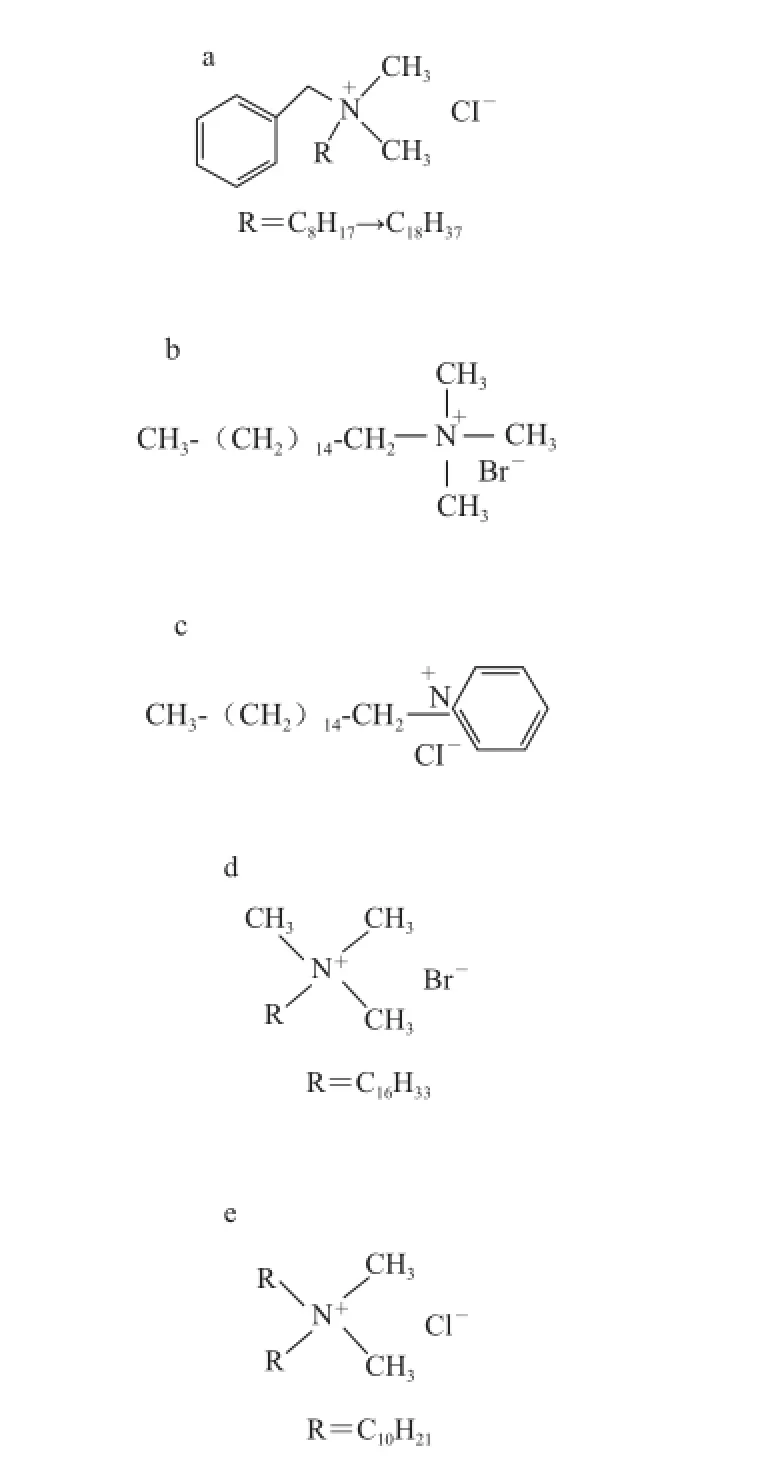

目前,用于卫生消毒的QACs种类主要有N-烷基二甲基苄基氯化铵(N-alkyl dimethyl benzyl ammonium chloride,A D BAC)、苯扎氯铵(benzalkonium chloride,BC)、溴化十六烷基三甲铵(cetyltrimethylammonium bromide,CTAB)、溴化溴棕三甲铵(cetrimide bromi de,CB)、氯化十六烷基吡啶(cetylpyridinium chloride,CTPC)、双十烷基二甲基氯化铵(N,N-didecyl-N,N-dimethylammonium chloride,DDAC)、司拉氯铵(stearalkonium chloride)及苄索氯铵(benzethonium chloride)等,其中BC、CTAB及ADBAC等已被广泛应用于食品工业,其中BC、CB等已使用超过40年[26],几种主要的QACs结构见图2。

a. ADBAC[28]/BC[29];b. CB[28];c. CTPC[28];d. CTAB[30];e. DDAC[27]。

图3 QACs反应机理示意图[26]Fig.3 C artoon showing the mechanism of action of QACs[26]

3 季铵盐类消毒剂作用机制及残留检测

3.1 作用机制

细菌细胞表面携带负电荷,常通过阳性离子维持细胞膜的稳定性。QACs是阳离子型表面活性剂和抗菌剂,可通过正电荷与细胞膜相互作用,其抗菌活性是N-烷基的功能。N-烷基赋予QACs亲脂性特征,通过阳性氮基团与细菌细胞膜上酸性磷脂的结合,疏水端整合入细菌疏水膜的核心,在高浓度时,QACs通过形成混合胶束聚集来溶解疏水细胞膜成分[26](图3)。总体来说,QACs发挥抗菌活性主要依靠破坏和变性蛋白和酶、破坏细胞膜整体性和使细胞内含物泄漏等[26,31]。对不同微生物的抗菌活性取决于烷基链的长度:链长12~14烷基的QACs对革兰氏阳性细菌和酵母表现最适活性;14~16烷基的QACs对革兰氏阴性细菌表现最适活性;链长小于4或大于18的QACs几乎无活性[26]。除对细菌具有抗菌活性,QACs消毒剂对一些病毒、真菌、酵母和原生动物也具有活性[32]。

3.2 残留检测

研究表明QACs残留可危害动物健康[33],食品中残留的季铵盐类消毒剂对人鼻上皮细胞有害,可引发、加重鼻炎[34]。同时,残留消毒剂可导致细菌耐药性,欧盟规定水果和蔬菜中QACs残留不得超过0.01 mg/kg,因此对季铵盐类消毒剂残留检测凸显重要。在众多方法中,高效液相色谱(high performance liquid chromatography,HPLC)、液相质谱(liquid chromatograph-mass spectrometer,LC-MS)方法被成功用于检测QACs[35]。Shen等[29]利用HPLC系统反相模式检测了阿奇霉素眼药水中的BC,选用Venusil- XBP(L)-C18(150 mm×4.6 mm,5 μm)柱,柱温50 ℃,流动相甲醇-磷酸钾 (16∶5,V/V),样品前处理中使用去蛋白步骤,结果表明HPLC是监测阿奇霉素眼药水中的BC含量的有效方法。 Ford等[36]建立了在HPLC结合电喷雾电离质谱方法基础上的对QACs定性及定量检测方法,对BC的检测限达到了3 ng/mL,且可同时检测苯基、双烷基二甲基氨盐化合物,此方法已成功应用于分析卫生采样装置、产品及游泳池水。MALDI-TOFMS方法亦被用于分析商业产品漱口水中QACs的组成,研究发现除了产品中标明的CPC、四烷基氨基氨盐化合物及三烷基氨盐化合物外,还包含一个复杂的氨盐类混合物[28]。以ABDAC、四烷基氨基氨盐化合物为检测对象,研究表明毛细血管电泳(capillary electrophoresis,CE)法要比电喷雾质谱分离效率高,检测限要高于两个数量级[37]。

4 大肠杆菌对季铵盐类消毒剂耐药性

4.1 大肠杆菌对消毒剂耐药性产生基础

QACs的使用是消毒剂抗性增加的潜在的重要动力,食品工业中QACs的广泛使用会导致细菌的适应和耐药菌的生长[5]。QACs可以有效减少食品中病原微生物,为了能快速杀死病原菌,在屠宰、肉类处理,特别是那些小且难接触到的区域,消毒剂的使用浓度要远高于它们对微生物的最小抑菌浓度[38-39],这种浓度可以达到千倍的最小抑菌浓度(minimal inhibitory concentration,MIC)值,而细菌要战胜快速、猛烈的消毒剂攻击并产生耐药生几乎是不可能的。大部分QACs在应用后不需要用水冲洗或冲洗不及时等,因此细菌与QACs的接触时间可以延长,长时间暴露于低浓度的QACs,可以使微生物处于亚抑制浓度中,如此,会使那些只对QACs高浓度MIC敏感的细菌才会生存下来[40],细菌对消毒剂的耐药性逐渐增大,最终导致消毒剂在食品行业中使用失败,并出现影响人类健康等严重的问题。

如今,对消毒剂耐药性研究的对象主要为革兰氏阳性菌中的葡萄球菌(Staphylococcus spp.),由于消毒剂的过量使用,导致葡萄球菌,特别是耐甲氧西林金黄色葡萄球菌(methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus,MRSA)对消毒剂的耐药。相对革兰氏阳性细菌,革兰氏阴性细菌对消毒剂表现出更强的抗性[9]。大肠杆菌对QACs消毒剂的MICs远高于葡萄球菌,如大肠杆菌对BC的MIC为50 mg/L,远高于葡萄球菌的0.5 mg/L[18],假单胞菌(Pseudomonas sp.)对BC的MIC达到了200 mg/L,远高于葡萄球菌的4~11 mg/L[41],革兰氏阴性细菌对QACs的高抗性源自于所携带的特异性耐药基因[42]。

4.2 大肠杆菌对季铵盐类耐药基因型

迄今为止,有7 种不同质粒介导的QAC特异的抗性基因在革兰氏阴性细菌大肠杆菌中被发现,包括qacE、qacEΔ1、qacF、qacG、qacH、qacI及sugE[43-45]。这些基因编码外排泵蛋白赋予对QACs的抗性,属于小多重抗性(small multiple resistance,SMR)蛋白家族[42,45],SMR家族基因可由质粒或整合子介导,对QACs高浓度MICs的菌株经常通过获得可移动基因元件,如质粒、1型整合子等获得这些消毒剂基因[46],而1型整合子大多存在于可接合的质粒上[47-48],因此,qac、sugE(p)基因可在革兰氏阴性细菌中水平及垂直传播[49-50]。由于质粒型消毒剂基因的可传播性,以及具有与抗生素耐药基因的共传播特性,相对于染色体编码QACs特异性耐药基因,qac、sugE(p)基因在消毒剂耐药中扮演着重要的角色。qacE、qacEΔ1基因发现存在于革兰氏阴性菌质粒上1型整合子3端[51-52],qacEΔ1基因是qacE基因的突变缺陷体[43]。QacEΔ1蛋白对季铵盐类消毒剂和染料的耐药水平低于QacE,这些差异是由于QacEΔ1蛋白失去了第四个跨膜片段和羧基末端的高度保守残基所造成的[53]。qacG基因报道由1型整合子介导[45],qacF、qacH、qacI基因与qacE的同源率达到67.8%,亦常发现于革兰氏阴性细菌质粒介导的整合子[54-55]、质粒pB8及IncP-1βpR751上[56]。与qac基因类似,sugE基因被发现存在于质粒,首先发现于肺炎克雷伯氏菌(Klebsiella pneumoniae)β-内酰胺药物抗性质粒pTKH11上[57],之后,从大肠杆菌、沙门氏菌分离的质粒上也检测出sugE(p)基因[39,58-60]。对于sugE基因,Chung等[61]认为大肠杆菌(E. coli)中的sugE的超量表达,表现出对部分QACs耐药;Son等[62]认为sugE仅仅可通过一个氨基酸突变即可表现出对QAC抗性。最新研究表明,qac、sugE(p)基因共存于多重耐药(multi drug resistance,MDR)质粒:InA/C、pSN254上[60],可介导高水平消毒剂耐药。

除以上基因之外,某些非特异性外排基因,如大肠杆菌[63]以及大肠杆菌O157∶H7[64]中质粒介导TehA基因[65],耐药节结化细胞分化(resistance nodulation cell division,RND)家族外排泵AcrAB-TolC也表现出对QACs的非特异性的耐药,但其表达与调控基因marOR、soxS的表达密切相关[10]。另有5 种染色体编码基因sugE(c)(染色体型sugE)、emrE、ydgE/ydgF及mdfA等也特异抗性地赋予对QACs的抗性,但不具传播性[66-67]。综上,质粒介导的QACs消毒剂耐药基因不仅在革兰阳性菌中已经流行,在革兰氏阴性菌中也已经存在,质粒介导消毒剂基因传播危害性较大,应引起重视。

4.3 大肠杆菌对季铵盐类耐药基因型与表型关系

不同的消毒剂基因介导对QACs的不同程度的耐药,目前,已知部分消毒剂基因与其表型之间的关系[18,66],但尚有基因与表型之间的关系未建立。鉴于相关流行病学调查不够系统、全面,关于qac基因型与表型之间的关系,有两种观点。一种观点主要基于对qacEΔ1基因的研究,此观点认为,qac基因介导低水平QACs抗性,不同qac基因携带株对QACs的MICs无明显差异[43]。在绿脓假单胞菌(Pseudomonas aeruginosa)中,qacEΔ1基因并没有对QACs成员之一的苯扎氯铵表现高抗性[68]。其中的一个解释是基于qac基因介导对众多阳离子化合物表现抗性,从而可能导致对QACs底物表现非高水平的特异性[66,69]。qac基因介导对QACs的抗性,同时可对30多种亲脂性阳离子化合物表现抗性,这些化合物至少隶属于12个不同的化学家族,包括单价阳离子化合物,如吖啶黄、结晶紫及绝大部分QACs等,双价阳离子化合物包括双胍类、联脒及部分QACs等[70]。qacEΔ1、qacE启动子的类型与表达水平也可能导致对QACs的低水平耐药[42]。然而另一观点认为,qac基因和对不同阳离子化合物抗性之间存在紧密的联系,由于qac基因的表达,细菌对消毒剂的抗性逐渐增加[71]。Smith等[72]研究发现qac基因阴性与阳性菌株间QACs的MICs有显著差异,携带qac基因菌株MIC值可为不携带该基因菌株的2 倍。质粒介导的qacG基因可使菌株对消毒剂的MIC值高于敏感菌株5 倍,且暴露在20 mg/L QAC中的存活时间高于敏感株1万 倍[73]。pNVH01质粒上携带的qacJ基因阳性菌株对BC和CATB消毒剂的MIC值分别高于阴性菌株的4.5~5.5 倍[46]。

除此之外,目前尚缺乏对革兰氏阴性细菌中qacF、qacH、qacI及sugE(p)等基因与消毒剂耐药表型关系的研究,因此,需系统调查质粒介导消毒基因的耐药表型,在此基础上,确立消毒剂基因与对QACs的MICs之间的对应关系。

4.4 季铵盐类消毒剂与抗生素耐药基因共传播

QACs被广泛使用,然而QACs对抗生素抗性的潜在的筛选压力却很少引起关注。Soumet等[74]评估了大肠杆菌菌株反复暴露于不同QACs后,对QACs和抗生素敏感性变化的影响,研究发现,菌株同时表现对QACs、抗生素的耐药,QACs在亚抑制浓度下的过度使用可导致对抗生素耐药菌株的筛选,并带来公共安全风险。QACs类消毒剂的暴露使用,发挥着筛选压力的 作用,并可以产生共耐药的基因,编码对消毒剂和抗生素的共同抗性[75]。从临床样品分离的高水平QAC的MICs值的大肠杆菌菌株同时与抗生素抗性密切相关[76],BC耐药菌株对大环内酯类、苯唑西林的耐药率明显高于非耐药菌[6]。细菌对消毒剂和抗生素抗性之间存在关联,消毒剂和抗生素可以共筛选(co-selection)同时具有对消毒剂和抗生素抗性的细菌。为了生存,共筛选的微生物必须获得对2 种以上不同抗菌物质的抗性。共筛选可以通过两种机制药发生,一种机制为交叉耐药(cross-resistance),指不同的药物对同一靶位作用或使用同一作用途径;一般由单个外排泵介导,同时可以泵出QACs和其他抗菌物质[77-78]。如葡萄球菌中qacC基因可赋予宿主对β-内酰胺药物的抗性[79]。另一种机制为共同耐药(coresistance),指赋予抗性表型的基因存在于同一个移动基因元件上,比如质粒或整合子。这些基因元件包括两个或更多的抗性基因或基因单位[80-81]。QACs和抗生素的共耐药被认为与医疗保健、食品设备中使用QAC有关[50]。不管是交叉耐药还是共同耐药,最终结果是一致的:即对一种药物抗性的发展同时伴随对另一种药物抗性的出现。在革兰氏阴性细菌中,qac基因经常存在于质粒介导的1型整合子上,这些整合子同时携带不同的抗生素抗性基因,因此,qac基因和抗生素耐药基因可同时表达,从而表现出共同耐药[82]。qacEΔ1基因常发现于1型整合子上,同时包括sul I磺胺类药物抗性基因[43,83],qacEΔ1亦被发现与新型金属β-内酰胺酶基因blaNDM-1同时存在于1型整合子上[84]。qacG基因与其他抗性基因blaIMP-4、aacA4、qnrB4等一起共存在沙门氏菌质粒I型整合子上[49]。sugE(p)基因发现与抗生素抗性基因blaCMY-2、sulI、aadA及tet RA等共存于大肠杆菌或沙门氏菌多重耐药质粒IncA/C、pSN254上[39,58-60]。在可移动的基因元件上携带QAC耐药基因可保证抗性通过水平基因转移传播于菌群中[50]。消毒剂抗性和抗生素抗性可以“共定植”,因此对其中一个筛选可导致另一个抗性的筛选[85]。

5 结 语

目前,国内外对食源性大肠杆菌耐药基因流行特征及耐药机制等研究尚不深入,调查食源性大肠杆菌消毒剂耐药基因流行特征及传播机制已经迫在眉睫,开展大肠杆菌对消毒剂耐药流行病学及机制研究,对防控消毒剂耐与抗生素药性与基因传播有着重要作用,为QACs的规范使用提供依据和理论基础,并为食品工业中食源性大肠杆菌及革兰氏阴性菌的防控提供科学依据。

[1] 史贤明, 施春雷, 索标, 等. 食品加工过程中致病菌控制的关键科学问题[J]. 中国食品学报, 2011, 11(9): 194-208.

[2] NYACHUBA D G. Foodborne illness: is it on the rise?[J]. Nutrition Reviews, 2010, 68(5): 257-269.

[3] MENG J, LT J, ZHAO T, et al. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli[M]//DOYLE M P, BUCHANAN R L. Food microbiology. 4thed. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology, 2013.

[4] SIDHU M S, SORUM H, HOLCK A. Resistance to quaternary ammonium compounds in food-related bacteria[J]. Microbial Drug Resistance, 2002, 8(4): 393-399.

[5] LANGSRUD S, SUNDHEIM G, BORGMANN-STRAHSEN R. Intrinsic and acquired resistance to quaternary ammonium compounds in food-related Pseudomonas spp.[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2003, 95(4): 874-882.

[6] ZMANTAR T, KOUIDHI B, MILADI H, et al. Detection of macrolide and disinfectant resistance genes in clinical Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci[J]. BMC Research Notes, 2011, 4(1): 453. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-453.

[7] LONGTIN J, SEAH C, SIEBERT K, et al. Distribution of antiseptic resistance genes qacA, qacB, and smr in methicillin-resistant Sta phylococcus aureus isolated in Toronto, Canada, from 2005 to 2009[J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2011, 55(6): 2999-3001.

[8] BISCHOFF M, BAUER J, PREIKSCHAT P, et al. First detectionof the antiseptic resistan ce gene qacA/B in Enterococcus faecalis[J]. Microbial Drug Resistance, 2012, 18(1): 7-12.

[9] CHAIDEZ C, LOPEZ J, CASTRO-del CAMPO N. Quaternary ammonium compounds: an alternative disinfec tion method for fresh produce wash water[J]. Journal of Water Health, 2007, 5(2): 329-333.

[10] BUFFET-BATAILLON S, le JEUNE A, le GALL-DAVID S, et al. Mol ecular mechanisms of higher MICs of antibiotics and quaternary ammonium compounds for Escherichia coli isolated from bacteraemia[J]. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2012, 67(12): 2837-2842.

[11] BUFF ET-BATAILLON S, TATTEVIN P, BONNAURE-MALLET M, et al. Emergence of resistance to antibacterial agents: the role of quaternary ammonium compounds-a critical review[J]. International Jounal of Antimicrobial Agents, 2012, 39(5): 381-389.

[12] SCH ROEDER C M, WHITE D G, MENG J. Retail meat and poultry as a reservoir of antimicrobial-resistant Escherichia coli[J]. Food Microbiology, 2004, 21(3): 249-255.

[13] 刘书亮, 张晓利, 韩新锋, 等. 动物性食品源大肠杆菌耐药性研究[J].中国食品学报, 2011, 11(7): 163-167.

[14] 邹立扣, 蒲妍君, 杨莉, 等. 四川省猪肉源大肠杆菌、沙门 氏菌分离与耐药性分析[J]. 食品科学, 2012, 33(13): 202-206.

[15] XIA X, MENG J, MCDERMOTT P F, et al. Escherichia coli from retail meats carry genes associated with uropathogenic Escherichia col i, but are weakly invasive in human bladder cell culture[J]. Journal Applied Microbiology, 2011, 110(5): 1166-1176.

[16] AZAP O K, ARSLAN H, SEREFHANOGLU K, et al. Risk factors for extende d-spectrum beta-lactamase positivity in uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from community-acquired urinary tract infections[J]. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2010, 16(2): 147-151.

[17] HAMER D H, GILL C J. From the farm to the kitchen table: the negat ive impact of antimicrobial use in animals on humans[J]. Nutrition Review, 2002, 60(8): 261-264.

[18] MCDONNELL G, RUSSELl A D. Antiseptics and disinfectants: activity, action, and resistance[J]. Clinical Microbiology Review, 1999, 12(1): 147-1 79.

[19] WILKS S A, MICHELS H T, KEEVIL C W. Survival of Listeria monocytogenes Scott A on metal surfaces: implications for crosscontamination[J]. International Journ al of Food Microbiology, 2006, 111(2): 93-98.

[20] WALTON J T, HILL D J, PROTHEROE R G, et al. Investiga tion into the effect of detergents on disinfectant susceptibility of attached Escherichia coli and Listeria monocyt ogenes[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2008, 105(1): 309-315.

[21] LANGSRUD S, SUNDHEIM G. Factors contributing to the survival of poultry associated Pseudomonas spp. exposed to a quaternary ammonium compound[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 1997, 82(6): 705-712.

[22] SCHMIDT R H. Basic elements of equipment cleaning and sanitizing in food processing and handling operations[M]. Universi ty of Florida: Institute of Food and Agriculture Sciences Extension, 2003.

[23] BJORLAND J, STEINUM T, KVITLE B, et al. Widespread distribution of disinfectant resistance genes among staphylococci of bovine and caprine origin in Norway[J]. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 2005, 43( 9): 4363-4368.

[24] BRAGG R R. Limitation of the spread and impact of infectious coryza through the use of a continuous disinfection programme[J]. Onde rstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research, 2004, 71(1): 1-8.

[25] BRAGG R R, PLUMSTEAD P. Continuous disinfection as a means to control infectious diseases in poultry: evaluation of a continuous disinfection pr ogramme for broilers[J]. Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research, 2003, 70(3): 219-229.

[26] GILBERT P, MOORE L E. Cationic antiseptics: diversity of action under a common epithet[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2005, 99(4): 703- 715.

[27] USEPA. Reregistration eligibility decision for aliphatic alkyl quaternaries (DDAC)[EB/OL]. 2006. http://www.regulations.gov.

[28] MORROW A P, KASSIM O O, AYORINDE F O. Detection of cationic surfac tants in oral rinses and a disinfectant formulation using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry[J]. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 2001, 15(10): 767-77 0.

[29] SHEN Y, XU S J, WANG S C, et al. Determination of benzalkonium chloride in viscous ophthalmic drops of azithromycin by highperformance liquid chromatography[J]. Journal of Zhejiang University Science B, 2009, 10(12): 877-882.

[30] HOSSEINZADEH R, MALEKI R, MATIN A A, et al. Spectrophotometric study of anionic azo-dye light yellow (X6G) interaction with surfactants and its micellar solubilization in cationic surfactant micelles[J]. Spec trochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 2008, 69(4): 1183-1187.

[31] IOANNOU C J, HANLON G W, DENYER S P. Action of disinfectant quaternary ammonium compounds against Staphylococcus aureus[ J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2007, 51(1): 296-306.

[32] FAZLARA A, EKHTELAT M. The disinfectant effects of benzalkonium chloride on some important foodborne pathogens[J]. American-Eurasian Journal of Agricultural & Environmental Sciences, 2012, 12(1): 23-29.

[33] HUT CHISON M. Ethical dilemmas for aged care[J]. Christian Nurse International, 1996, 12(1): 10-11.

[34] MERIANOS J J. Quaternary ammonium antimicrobial compounds[M]//BLOCK S S. Disinfection, sterili-zation and preservation. 4thed. Malvern, PA: Lea & Febiger, 1991.

[35] TEZEL U. Fate and effect of quaternary ammonium compounds in biological systems[D]. Atlanta, Georgia: Georgia Institute of Technology, 2009.

[36] FORD M J, TETLER L W, WHITE J, et al. Determination of alkyl benzyl and dialkyl dimethyl quate rnary ammonium biocides in occupational hygiene and environmental media by liquid chromatography with electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry and tandem mass spectrometry[J]. Journal of Chromatography A, 2002, 952(1/2): 165-172.

[37] BUCHBERGER W, SCHOFTNER R. Determination of lowmolecular-mass qua ternary ammonium compounds by capillary electrophoresis and hyphenation with mass spectrometry[J]. Electrophoresis, 2003, 24(12/13): 2111-2118.

[38] THEVENOT D, DERNBURG A, VERNOZY-ROZAND C. An updated review of Listeria monocytogenes in the pork meat industry and its products[J]. Journal Applied Microbiology, 2006, 101(1): 7-17.

[39] ZHAO S, BLICKENSTAFF K, GLENN A, et al. beta-Lactam resistanc e in Salmonella strains isolated from retail meats in the United States by the National Antimicrobial Re sistance Monitoring System between 2002 and 2006[J]. Applied Environmental Microbiology, 2009, 75(24): 7624-7630.

[40] MCBAIN A J, RICKARD A H, GILBERT P. Possible imp lications of b iocide accumulation in the environment on the prevalence of bacterial antibiotic resistance[J]. Journal of Industrial Microbiology a nd Biotechnology, 2002, 29(6): 326-330.

[41] GILBERT P, MCBAIN A J. Potential impact of increased use of biocides in consumer products on prevalence of antibiotic resistance[J]. Clinical Microbiology Review, 2003, 16(2): 189-208.

[42] BAY D C, ROMMENS K L, TURNER R J. Small multidrug resistance proteins: a multidrug transporter family that continues to grow[J]. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 2008, 1778(9): 1814-1838.

[43] KUCKEN D, FEUCHT H, KAULFERS P. Association of qacE and qacEDelta1 with multiple resistance to antibiotics and antisep tics in clinical isolates of Gram-negative bacteria[J]. FEMS Microbiology Letter, 2000, 183(1): 95-98.

[44] PLOY M C, COURVALIN P, LAMBERT T. Characterization of In40 of Enterobacter aerog enes BM2688, a class 1 integron with two new gene cassettes, cmlA2 and qacF[J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 1998, 42(10): 2557-2563.

[45] LI D, YU T, ZHANG Y, et al. Antibiotic resistance characteristics of environmental bacteria from an oxytetracycline production wastewat er treatment plant and the receiving river[J]. Applied Environmental Microbiology, 2010, 76(11): 3444-3451.

[46] BJORLAND J, STEINUM T, SUNDE M, et al. Novel plasmid-borne gene qacJ mediates resistance to quaternary ammonium compounds in e quine Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus simulans, and Staphylococcus intermedius[J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2003, 47(10): 3046-3052.

[47] KANG H Y, JEONG Y S, OH J Y, et a l. Characterization of antimicrobial resistance and class 1 integrons found in Escherichia coli isolates from humans and animals in Korea[J]. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 2005, 55(5): 639-644.

[48] VO A T, van DUIJKEREN E, GAASTRA W, et al. Antimicrobial resistance, class 1 integrons, and genomic island 1 in Salmonella isolates from Vietnam[J]. PLoS One, 2010, 5(2): e9440.

[49] LI X Z, NIKAIDO H. Efflux- mediated drug resistance in bacteria: an update[J]. Drugs, 2009, 69(12): 1555-1623.

[50] CHAPMAN J S. Disinfectant resistance mechanisms, crossresistance, and co-resistance[J]. International Biodeterioration and Biodegradation. 2003, 51(4): 271-276.

[51] PAULSEN I T, LITTLEJOHN T G, RADSTROM P, et al. The 3’conserved segment of integrons contains a gene associated with multidrug resistance to antiseptics and disinfectants[J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 1993, 37(4): 761-768.

[52] CHEN L, CHAVDA K D, FRAIMOW H S, et al. Complete nucleotide sequences of blaKPC-4- and blaKPC-5-harboring IncN and IncX plasmids from Klebsiella pneumoniae strains isolated in New Jersey [J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2013, 57(1): 269-276.

[53] KAZAM A H, HAMASHIMA H, SASATSU M, et al. Characterization of the antiseptic-resistance gene qacE delta 1 isolated from clinical and environmental isolates of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio cholerae non-O1[J]. FEMS Microbiology Letter, 1999, 1 74(2): 379-384.

[54] CHANG C Y, LU P L, LIN C C, et al. Integron types, gene cassettes, antimicrobial resistance genes and plasmids of Shigella sonnei isolates from outbreaks and spor adic cases in Taiwan[J]. Journal of Medical Microbiology, 2011, 60(2): 197-204.

[55] WANNAPRASAT W, PADUNGTOD P, CH UANCHUEN R. Class 1 integrons and virulence genes in Salmonella enterica isolates from pork and humans[J]. International Jounal of Antimicrobial Agents, 2011, 37(5): 4 57-461.

[56] SCHLUTER A, HEUER H, SZCZEPANOWSKI R, et al. Plasmid pB8 is closely related to the prototype IncP-1beta plasmid R751 but transfers poorly to Escherichia coli and carries a new transposon encoding a small multidrug resistance effl ux protein[J]. Plasmid, 2005, 54(2): 135-148.

[57] WU SW, DORNBUSCH K, KRONVALL G, et al. Characterization and nucleotide sequence of a Klebsiella oxytoca cryptic plasmid encoding a CMY-type beta-lactamase: confirmation that the plasmid-mediated cephamycina se originated from the Citrobacter freundii AmpC beta-lactamase[J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy,1999, 43(6): 1350-1357.

[58] CALL DR, SINGER RS, MENG D, et al. blaCMY-2-positive IncA/C plasmids from Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica are a distinct component of a larger lineage of plasmids[J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2010, 54(2): 590-596.

[59] WELCH T J, EVENHUIS J, WHITE D G, et al. IncA/C plasmidmediated florfenicol resistance in the catfish pathogen Edwardsiella ictaluri[J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2009, 53(2): 845-846.

[60] WELCH T J, FRICKE W F, MCDERMOTT P F, et al. Multiple antimicrobial resistance in plague: an emerging public health risk[J]. PLoS One, 2007, 2(3):e309.

[61] CHUNG Y J, SAIER M H, Jr. Overexpression of the Escherichia coli sugE gene confers resistance to a narrow range of quaternary ammonium compounds[J]. Journal of Bacteriology, 2002, 184(9): 2543-2545.

[62] SON M S, del CASTILHO C, DUNCALF K A, et al. Mutagenesis of SugE, a small multidrug resistance protein[J]. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2003, 312(4): 914-921.

[63] LANGSRUD S, SUNDHEIM G, HOLCK A L. Cross-resistance to antibiotics of Escherichia coli adapted to benzalkonium chloride or exposed to stress-inducers[J]. Journal Applied Microbiology, 2004, 96(1): 201-208.

[64] BRAOUDAKI M, HILTON A C. Adaptive resistance to biocides in Salmonella enterica and Escherichia coli O157 and cross-resistance to antimicrobial agents[J]. Journal Clinical Microbiology, 2004, 42(1): 73-78.

[65] TURNER R J, TAYLOR D E, WEINER J H.Expression of Escherichia coli TehA gives resistance to antiseptics and disinfectants similar to that conferred by multidrug resistance efflux pumps[J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 1997, 41(2): 440-444.

[66] BAY D C, TURNER R J. Diversity and evolution of the small multidrug resistance protein family[J]. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 2009, 9: 140. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-140.

[ 67] EDGAR R, BIBI E. MdfA, an Escherichia coli multidrug resistance protein with an extraordinarily broad spectrum of drug recognition[J]. Journal of Bacteriology, 1997, 179(7): 2274-2280.

[ 68] ROMAO C, MIRANDA C A, SILVA J, et al. Presence of qacEDelta1 gene and susceptibility to a hospital biocide in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa resistant to antibiotics[J]. Curruent Microbiology, 2011, 63(1): 16-21.

[ 69] GRKOVIC S, HARDIE K M, BROWN M H, et al. Interactions of the QacR multidrug-binding protein with structurally diverse ligands: implications for the evolution of the binding pocket[J]. Biochemistry, 2003, 42(51): 15226-15236.

[ 70] HASSANIN A. Phylogeny of Arthropoda inferred from mitochondrial sequences: strategies for limiting the misleading effects of multiple changes in pattern and rates of substitution[J]. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 2006, 38(1): 100-116.

[ 71] BEHR H, REVERDY M E, MABILAT C, et al. Relationship between the level of minimal inhibitory concentrations of five antiseptics and the presence of qacA gene in Staphylococcus aureus[J]. Pathologie Biologie (Paris), 1994, 42(5): 438-444.

[ 72] SMITH K, GEMMELL C G, HUNTER I S. The association between biocide tolerance and the presence or absence of qac genes amonghospital-acquired and community-acquired MRSA isolates[J]. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 2008, 61(1): 78-84.

[ 73] HEIR E, SUNDHEIM G, HOLCK A L. The qacG gene on plasmid pST94 confers resistance to quaternary ammonium compounds in staphylococci isolated from the food industry[J]. Journal Applied Microbiology, 1999, 86(3): 378-388.

[ 74] SOUMET C, FOURREAU E, LEGRANDOIS P, et al. Resistance to phenicol compounds following adaptation to quaternary ammonium compounds in Escherichia coli[J]. Veternary Microbiology, 2012, 158(1/2): 147-152.

[ 75] CARSON R T, LARSON E, LEVY S B, et al. Use of antibacterial consumer products containing quaternary ammonium compounds and drug resistance in the community[J]. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 2008, 62(5): 1160-1162.

[ 76] BUFFET-BATAILLON S, BRANGER B, CORMIER M, et al. Effect of higher minimum inhibitory concentrations of quaternary ammonium compounds in clinical E. coli isolates on antibiotic susceptibilities and clinical outcomes[J]. Journal of Hospital Infection, 2011, 79(2): 141-146.

[ 77] HUET A A, RAYGADA J L, MENDIRATTA K, et al. Multidrug efflux pump overexpression in Staphylococcus aureus after single and multiple in vitro exposures to biocides and dyes[J]. Microbiology, 2008, 154(10): 3144-3153.

[ 78] MASEDA H, HASHIDA Y, KONAKA R, et al. Mutational upregulation of a resistance-nodulation-cell division-type multidrug efflux pump, SdeAB, upon exposure to a biocide, cetylpyridinium chloride, and antibiotic resistance in Serratia marcescens[J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2009, 53(12): 5230-5235.

[ 79] FUENTES D E, NAVARRO C A, TANTALEAN J C, et al. The product of the qacC gene of Staphylococcus epidermidis CH mediates resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics in gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria[J]. Research in Microbiology, 2005, 156(4): 472-477.

[ 80] SCHLUTER A, SZCZEPANOWSKI R, PUHLER A, et al. Genomics of IncP-1 antibiotic resistance plasmids isolated from wastewater treatment plants provides evidence for a widely accessible drug resistance gene pool[J]. FEMS Microbiology Review, 2007, 31(4): 449-477.

[ 81] NORMAN A, HANSEN L H, SHE Q, et al. Nucleotide sequence of pOLA52: a conjugative IncX1 plasmid from Escherichia coli which enables biofilm formation and multidrug efflux[J]. Plasmid, 2008, 60(1): 59-74.

[ 82] ZHAO W H, CHEN G, ITO R, et al. Identification of a plasmid-borne blaIMP-11 gene in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae[J]. Journal of Medical Microbiology, 2012, 61(2): 246-251.

[ 83] KAZAMA H, HAMASHIMA H, SASATSU M, et al. Distribution of the antiseptic-resistance genes qacE and qacE delta1 in gram-negative bacteria[J]. FEMS Microbiology Letter, 1998, 159(2): 173-178.

[ 84] YONG D, TOLEMAN M A, GISKE C G, et al. Characterization of a new metallo-beta-lactamase gene, bla(NDM-1), and a novel erythromycin esterase gene carried on a unique genetic structure in Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 14 from India[J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2009, 53(12): 5046-5054.

[ 85] CIRIC L, MULLANY P, ROBERTS A P. Antibiotic and antiseptic resistance genes are linked on a novel mobile genetic element: Tn6087[J]. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 2011, 66(10): 2235-2239.

Progress in Research on the Resistance of Escherichia coli to Quaternary Ammonium Compounds (QACs)

ZOU Li-kou1, WU Guo-yan1,2, CHENG Lin1, HE Xue-mei1,2, GUO Li-juan1,2, LONG Mei1,2

(1. Laboratory of Microbiology, Dujiangyan Campus of Sichuan Agricultural University, Dujiangyan 611830, China; 2. College of Resources and Environment, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu 611130, China)

Current studies have demonstrated the serious disinfectant resistance in food-borne bacteria. Escherichia coli as an indicator bacterium for food contamination and drug resistance reveals much higher resistance to quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs) than do Gram-positive bacteria. In addition, the resistance to QACs and antibiotics can be disseminated and co-transmitted, thus resulting in co-selected disinfectant and antibiotics-resistant bacteria. Therefore, the chemical structure, species and mechanism of action of QACs, the genetic mechanism as well as genotype and phenotype underlying QACs resistance of Escherichia coli, and the mechanism of co-transmission with antibiotic resistance are summarized in this article. To date, little is known about the mechanism of disinfectant resistance in food-borne E. coli. Thus, further research on the disinfectant resistance is needed. Understanding the mechanism of QACs resistance of E. coli can provide a theoretical and scientific basis for regulating the use of disinfectants and preventing food-borne E. coli infections.

Escherichia coli; quaternary ammonium compounds; disinfectant; antibiotic resistance

Q93;TS207.4

A

1002-6630(2014)17-0338-08

10.7506/spkx1002-6630-201417063

2013-08-07

四川省教育厅重点基金项目(10ZA055);四川省教育厅青年基金项目(13ZB0282);教育部“长江学者和创新团队发展计划”项目(IRT13083)

邹立扣(1979—),男,教授,博士,研究方向为微生物分子生物学、食品安全。E-mail:zoulkcn@hotmail.com